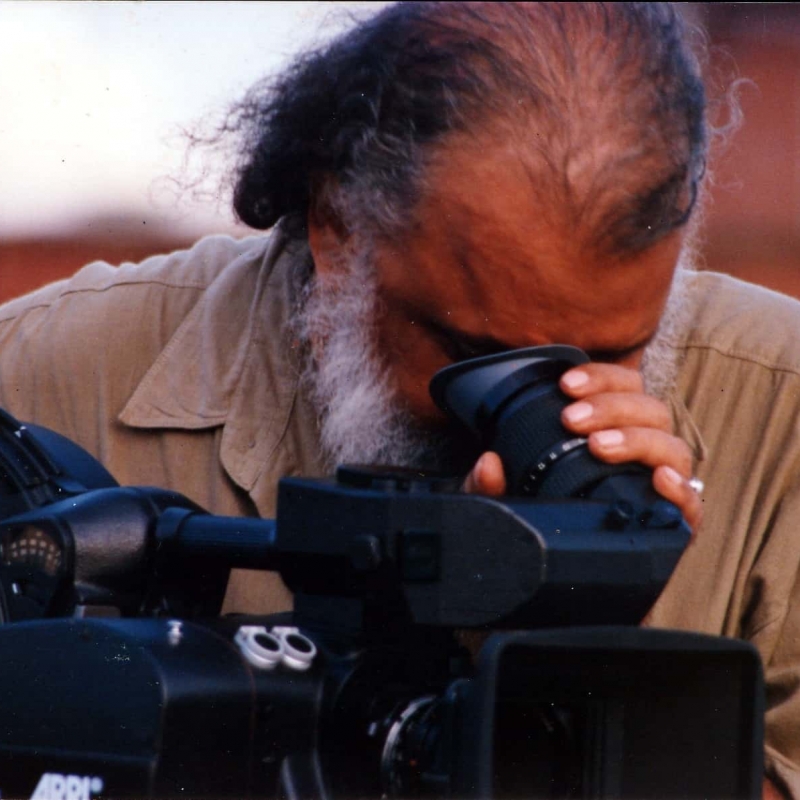

Govindan Aravindan, popularly known as G. Aravindan, left behind a legacy of 11 feature films and several documentaries. Besides these, he produced one of the longest-running commentaries on contemporary society in Kerala through his weekly cartoon page, which ran from 1961 to the early 1970s. His theatre productions revived the ‘original (thanathu) Malayalam’ theatre and left a deep impression on Malayali cultural consciousness. Aravindan is not just remembered for his contributions of good films, or art house films, but is celebrated as a multi-faceted creative genius in Kerala.

Even 26 years after his death, Aravindan is honoured annually with a memorial lecture at the International Film Festival of Kerala. Aravindan’s films are screened across Kerala and other National Festival circles, year after year. He made mystical and contemplative films, some of which transcended his time. ‘Aravindan's approach to narrative was a substratum of emotion rather than emotion being an adjunct to narrative. He also showed deep compassion for the eccentric, the marginalized and alienated,’ noted Gönül Donmez-Colin, an independent researcher and writer (n.d.).

Aravindan’s first film, Uttarayanam (The Throne of Capricorn, 1974), like many of his later films, was an extension of his long-running cartoon series Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (Small Men and the Big World, 1963-71). The series was a commentary on the contemporary realities of Kerala at the time. The cartoonist in him entertained a generation in Kerala which, when considered along with his films, evoked a philosopher and a mystic humanist.

Aravindan the cultural icon

Any analysis of Aravindan the film maker must start with an understanding of the man himself, and the cultural context within which he worked. He was the son of M.N. Govindan Nair, a Malayalam satire writer, and grew up in the company of writers in the town of Kottayam, where the first writers’ cooperative publishing house was founded. Incidentally, Kottayam was also the first to be declared a ‘one hundred per cent’ literate district in the country by the Government of India.

Aravindan was deeply interested in drawing and painting as a child. Later in his youth days, he developed an interest in music. He studied Hindustani music just to be able to enjoy it more deeply. A. Ramachandran, a friend of Aravindan's and a renowned painter trained at Rabindranath Tagore’s Shantiniketan, introduced him to Bengali art and culture and even Rabindra Sangeet. Aravindan used to sing Rabindra Sangeet in Kerala, wherever he was asked to speak, making the genre popular in the State.

He was deeply involved in theatre in Kerala for several years and developed a keen interest in films in the 1960s. Adoor Gopalakrishnan, a graduate of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), introduced him to the new medium. In a commemorative volume that was released on Aravindan’s 75th birthday, and published by the Kerala Chalachitra Academy, Adoor Gopalakrishnan wrote, ‘If you look at the cartoon series, Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum after 1965, one can make out his interest and affinity towards the new film movement (Aravindan 2010:15).' Indeed, Aravindan was the art director of Adoor’s first film, Kamini (1969), though the film was later abandoned.

‘The craft of film-making was unknown to Aravindan, but he became a film maker. He had a unique humane creativity under layered by painting, music and sculpture, which no other film maker before and after him could claim,’ wrote S. Jayachandran Nair, the iconic Malayalam editor, in his review of Aravindan’s work (Aravindan 2010:19).

Malayalam modernist poet Ayyappa Panicker noted Aravindan’s cinematic vision during a discussion on his film, Kanchana Sita (Golden Sita). ‘Just as C.N. Sreekantan Nair interpreted Ramayana in his play, Aravindan too has given it his own individualistic, cinematic interpretation and vision. He has freely done it as director and hence will call the film as Aravindayanam’, the English professor-cum-poet noted. The original author of the play, C.N. Sreekantan Nair, trusted Aravindan so much that the playwright did not even bother to look at the script Aravindan had written when the latter hosted him at Thiruvananthapuram’s (then) most famous artist joint—Nikunjam.

A look at the 12 documentaries directed by Aravindan offers a complete picture of his worldview. His first documentary was on the iconic writer and social reformist, V.T. Bhattathiripad. He also made a series of films on environmental issues. A few of his documentaries were about traditional art forms, including a seven-part series on Bharatanatyam. Aravindan made two biopics on J. Krishnamurti, a philosopher, for the Films Division of India, and one on the artist Namboothiri, who was also a painter and illustrator. He also made a few films on public health issues for CARE (an NGO working towards poverty alleviation and social injustice). The subjects of the documentaries show that he was a man with a modern social vision. The documentaries also indicate that he was thinking ahead of his time, by participating in reformist and modernist discourses.

To understand Aravindan’s films, key phrases are ‘affinity to films’, ‘unique humane creativity’, even with the limitations of film, and an ‘individualistic cinematic interpretation and vision’. All this, while staying deeply rooted to Kerala’s culture and contemporary social life. Even though Aravindan shot two of his films outside of Kerala—Kanchana Sita (in the Godavari plains of Andhra) and Vasthuhara (The Dispossessed) (in Kolkata)—his artistic and aesthetic sense was deeply etched in Malayalam culture and traditions.

The late Govindan Aravindan (a cartoonist by profession), considered by many as a poet-philosopher with a vision, swaying between the lyrical, mystical, and transcendental, made his first film Uttarayanam in 1974 (Donmez-Colinn.d.).

Uttarayanam: His first film

His first film was an extension of his cartoon series, in which he commented on the slide of society in Kerala after the freedom struggle, during the optimistic Nehruvian era. The 1960s were marked by frustration and discontent, as the progress envisaged by the freedom fighters was not moving at the pace of young people’s expectations. Making a sharp contrast between the sacrifices of the freedom fighters and the young frustrated son of a martyr to the cause of freedom, Aravindan went about making his first film. It followed a similar format to his cartoon series, where Guruji and young Ramu take us through Aravindan’s vision of contemporary reality.

The film revolves around a young protagonist and a colleague of his father, another freedom fighter. The colleague paints masks for a living, and sarcastically remarks that he hopes to make a small unit to cater to the market demands of a self-effacing population. Through black-and-white visuals, Aravindan draws a gloomy picture of the contemporary reality of the 1960s and 1970s. With cameraman Mankada Ravi Varma’s visuals, Aravindan’s beautifully crafted film fleshes out the typical Malabari Malayali lifestyle.

No one can forget the shot of Ravi’s (the protagonist) father’s body lying on his own doorstep, covered in ants—he had been killed by the British police. Ravi’s grandfather is a Gandhian satyagrahi, while his father is a radical. Ravi does not choose either side, and chooses to burn his own mask, making a statement of himself and the director at the end sequence of the film. Like his 11th film, this was among the few that had a definite storyline, dramatic events, and fleshed out characters, indicating his effort to reach the widest possible audience.

This first film, produced by his friends in Kozhikode, where he was posted as a Rubber Board officer, bagged a special jury mention at that year’s national film festival. The film won the best film award at Kerala’s yearly film honours. Malayalis who knew Aravindan, the long-standing, socio-political cartoonist for over a decade, gladly embraced the film maker and placed him alongside Adoor Gopalakrishnan, an FTII graduate who had already taken Malayalam films to national and international audiences. ‘I could sense what Uttarayanam, the film, will be even before reading the scripts, by looking at the people associated with it. The actors were Balan K Nair (a Bharat award winner later), theatre veteran Kunjandi, Premji, who were all legends. Those came to witness the shooting included the who’s who of literature and culture’, recollected the ace cameraman of the film, Mankada Ravi Varma (Aravindan 2010:97).

The year was 1976, and Malayalam films were receiving attention at national film festivals, with Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s first film Swayamvaram (1972) winning four national awards and M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s first film, Nirmalyam (Offerings, 1973), winning two national awards, one for Best film and Best Actor for P.J. Antony and a few state awards. With Aravindan’s first film, the list of nationally- and internationally-noted Malayalam films increased, heralding a ‘new wave’ of films. Uttarayanam bagged a special jury mention at the national awards given in the 25th year of India’s Independence. It also won best film honours at the state awards. K. Ravindran Nair (Ravi) of General Pictures, a cashew exporter who also produced family dramas, turned his eye to this ‘new wave’ and decided to produce films with Adoor and Aravindan. He gave them a free hand to explore their creativity in films, furthering the creative surge in Malayalam films.

Kanchana Sita as Aravindayanam

With Kanchana Sita, Aravindan’s second film, a true auteur's film was born. As Dr Ayyappa Paniker mentioned, it was an ‘Aravindayanam’, an Aravindan interpretation of the post-Lanka part of the Ramayana. The film was based on the director’s interpretation of the last portion of Ramayana, which was in turn, based on a play by C.N. Sreekantan Nair.

Fully utilising the creative freedom granted by the producer, Aravindan shifted from a structured story to film his own version of Ram and Lakshman in the plains of the Godavari, that too in the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh. He did find an elegant tribal who played Rama, and a short, pockmarked Lakshman, and went on to surprise all with the new style and interpretation of Ramayana, shocking audiences across the world. But for his limitations of being an untrained film director and the equipment that was available to them, with this effort Aravindan would have been able to placed in the genre of philosophical filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman and Tarkovsky. His interpretation of Rama and Sita as man and nature surpassed even the vision of the original playwright, C.N. Sreekantan Nair. Aravindan chose to characterise Sita as Mother Nature and did not cast anyone in the role, unlike most mythological films.

The film put Aravindan in a very small circle of philosopher directors from the world of films. The ambience, visuals, and narrative style of Kanchana Sita underlined an emerging feature that was unique to Aravindan’s mystic and contemplative cinema. However, being inexperienced, the effort was just short of great as the ideas and situations did not translate perfectly into cinematic language and experience. To this extent, a desperate Rama, running against the rising sun, shouting ‘Sita, Sita’ looks baffling at one level, as it is one of those rare moments in which a character moves even faster than the film. As fellow film maker John Abraham mentioned later, it was weighed down by the heavy literary symbolism, preventing it from speaking for itself as a film. Aravindan used silence and slow movements so much that the horse (Yagaswam) in the film, which also runs seldom, became a local metaphor for Aravindan’s films after Kanchana Sita.

The film remains shocking to audiences even today, just like the films of some of Aravindan’s favourite directors like Mani Kaul and Andrei Tarkovsky. It was shocking for its visionary approach, visual quality, characterisation, and the slow-paced, innovative style. Never in Indian films had Lord Rama been portrayed as a tribal leader living in a cave and Sita as a deity of nature. ‘The film is about the separation of man and nature and the influence of nature on man which leads the man Ram finally to leave his throne and go on a pilgrimage to join the nature. The film ends when Sita (nature) engulfs the man (Ram). This vision is even different from the original play, which the film was based on, though the play gives a hint about such a relationship (man and nature)’, noted Kavalam Narayana Panicker and a close theatre associate of Aravindan, in a discussion about the film (Aravindan 2010:114).

Thampu - The location film

His third film, Thampu (Tent, 1978), was also produced by Ravi, and has been described as a ‘location’ film by Aravindan himself. It is about a circus group which lands up on the historic banks of the Bharathappuzha (River Bharatha) in North Kerala. Thus, the sleepy village is in a state of excitement due to the arrival of the circus. Later, when a local festival occurs, the circus is overshadowed, causing it to pack up and move to another destination, attracting a young man disillusioned with life from the village with it.

Unlike his earlier films, Aravindan does not appear to make a strong statement in this film. It seems to have become lost in the details of the villagers’ lives and their excitement over the circus. The film is full of close-up examinations of the sense of wonderment permeating the village population, young and old. Typical of Aravindan, the film was shot without a pre-written script. The dialogue was written on the set as the shooting was in progress. Staying true to his meditative style, Aravindan caught the attention of maestros like Satyajit Ray. ‘I had planned the film as a reflection on real life. The film was shot at the village Thirunavaya on the banks of Bharathapuzha (river). We went there with about 15 circus artists. There was no pre-written script. We filmed the events as it unfolded. We invited the villagers to witness the circus performance and many of them were seeing it for the first time. We did not direct them, as after few days of their acquaintance with the lights and camera, when they were totally immersed in the circus acts, we shot their responses’, Aravindan told an interviewer later (Aravindan 2010:121). The highlight of the film was the lyrical and reflective quality of Aravindan’s films, which the director later became famous for.

The film caught the eye of film maker Satyajit Ray and was commented on as a film with a 'fascinating style' by Ray's friend and film writer Chidananda Das Gupta. He writes, 'Wordless observation is also the forte of G Aravindan's Thampu (The Tent 1978), but by pushing the realism to its logical, unstructured, conclusion, the director makes his fascinating style somewhat untenable for a full length feature (Das Gupta 1980).'

Kummatty - Kavalam enters Aravindan’s films fully

As Thampu bagged national and state awards, Aravindan went on to make three more films with Ravi, who gave him complete freedom to pursue his auteur film-making style. However, none of the films ever went on to become hits in the box office, though they all got 'noon show' releases in Kerala. His next film, Kummatty (The Bogeyman, 1979), was made for children, but again in the mystical and surrealistic Aravindan style. The film was conceived by Aravindan, based on a theatrical piece, Thanathu (original/indigenous), by Kavalam Narayana Panicker.

Kummatty is a mythical character with magical powers. To children, he is an old man full of fun, with magical powers to create the favourite animals of the children in the village. As Kummatty sings along the village tracks near the school, the kids follow him like rats to a piper. But to the old lady in the village, Kummatty marks the arrival of death. Kummatty transforms one child into a dog—he remains stuck for some time like this until he is freed to become a boy again. The boy returns home and releases a caged parrot he keeps, a symbolism of the ultimate freedom of human and nature’s spirits.

Incidentally, the amateur actor who portrayed Kummatty in the film died without seeing his own performance, giving another magical aspect to the film. The film was shot in a scenic village in the northern Malabar region of Kerala. Many describe it as an ‘adults’ children film’, as it had all the trappings of an Aravindan film and the folklore touch of Kavalam, the writer, which enabled it to hold not only the attention of children, but that of adults as well. It is never mentioned as a successful children’s film though, as Aravindan’s style was not very child-friendly, despite being a cartoonist. The film bagged many state awards.

Kottayam and its magical realism

Aravindan was born in Kottayam, where he grew up on the foothills of the Western Ghats. Kottayam, for many and especially for Malayalam literature, is like the magical realist town of Macondo, as described by Gabriel Garcia Marquez in a 1967 Spanish novel. The town was not just the birthplace of two film makers, namely Aravindan and John Abraham, it was also the headquarters of the largest-selling Malayalam newspaper in Kerala, and home to many a publishing house, including the first writer’s cooperative of India. It was also a centre of the rubber and plantation economy of Kerala.

The town and its people exerted a lot of influence on the people of Kerala, as it was the first centre of many early Christian educational institutions too. The Roman Catholic church even has two ‘blessed’ clergy from the district. It also had a Hindu Siddha Yogi who claimed to have lived for 300 years and performed many miracles, according to local legends. Overall the district and the town Kottayam had the aura of an Indian Macondo with its uniqueness. When Aravindan went on to make the film Esthappan (‘Stephen’ in English) about a miracle man in a coastal plain of Kerala, it was an expression of the 'unique and special magical realism', which he had inherited from his ancestral town, where he grew up.

Esthappan - The miracle man

'Just before he made the film Esthappan, Aravindan wrote to me. The film’s protagonist is a wandering miracle man. Some of these acts are from the miracles which Prabhakara Siddha Yogi has shown in Kottayam during our early days in the town. The yogi claims to be over 300 years old and legend has it that he met even King Marthanda Varma (lived over 300 years back) who established Travancore as a kingdom by uniting many small local kingdoms. Aravindan’s father had written an article on the Yogi too. Esthappan too performs many miracles like the Yogi. Aravindan has portrayed what he heard and seen about the Yogi and not bothered to examine the facts behind these “miracles”,’ writes Dr S.P. Ramesh, a younger cousin of Aravindan, who collaborated on many of his films (Aravindan 2010:49).

Just like Kummatty, the film Esthappan operates on the aspect of magical realism. The protagonist is an established painter, who goes around the shores of Kerala with incense, and stays around the churches of the area among the poorer fishermen. His actions are a topic of conversation among the fisher-folk, and he slowly gains a reputation of being a miracle man who amuses the children in the area. On one level, the film operates on the planned narrative of the story of a miracle man. On another level, it explains the phenomena of how local myths are born. Depending on the religious affinity of the miracle man, he or she is adopted by the religion to which they belong. The film, which was made on the same shores as Mata Amritanandamayi, a local Hindu godly woman with supposed magical powers, later emerged as being prophetic.

As a prominent critic observed, ‘We have two types of film-makers. One who thinks on the lines of the audiences and the other who makes the audience think on the lines of the film. Aravindan is in the second category through the aesthetically crafted film—Esthappan (Aravindan 2010:135).' The film also has some memorable music created by creative collaborators such as Isaac Thomas Kottukapally and Kavalam, which helped Aravindan to pull off the world of magical realism. The camera work of Shaji N. Karun, amplified magic of the film too.

Aravindan: The experimentalist

Aravindan, dabbled in various genres of art and culture but had an equally deep awareness about the social reality of his times. This gave even his experimental films a touch of social reality.

Pokkuveyil (The Light at Dusk 1982), which featured the young radical poet Balachandran Chullikkad in the lead role, was true to his individualistic, auteur style, which can be truly called experimental in nature. The film, shot on the banks of a freshwater lake in the Kollam district, had a unique but strange format. Aravindan edited the film based on the notes of the flute and sarod of two eminent musicians—an experiment that no other filmmaker had previously attempted India or abroad. Hariprasad Chaurasia on the flute and Rajeev Taranath on the sarod created the music that set the pace and mood of the film. The film moved in progression with the storyline, where a young hero ends up in a mental asylum, following many ups and downs in his life. ‘The film flows according to the structure of the music, 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4… like that. First, you see the house, then Nisha, then the sportsman, the radical Joseph, again the girl, girl…the shots are repeated in the same fashion. After the girl leaves the scene, the structure changes and it gains speed. I thought it the right way to portray the protagonist Balu’s chequered life’, Aravindan explained in an interview (Aravindan 2010:140).

The general audience, being unfamiliar with the nuances of classical music, reacted to the film bluntly. Even young film enthusiasts were flabbergasted. A young lady from Delhi even asked Aravindan whether the protagonist of the film was ‘impotent’ during a post-screening discussion. Clearly, Aravindan had failed, sending out mixed signals about the film and his auteur style. However, he was honoured at the national film festival that year, for his bold experiment and at the state awards as the second-best film of the year. Incidentally, this was the last film produced by Ravi.

Change in style

In his next film, Chidambaram (1985), produced by his own group, Aravindan went back to a definite story-based narration. The film was an adaptation from a work by his favourite short story writer, C.V. Sreeraman. The film, which featured Smita Patil, Bharat award winner (for best actor) Gopi, and Sreenivasan, was shot at the site of the Indo-Swiss animal husbandry project, in the scenic Mattupetty hamlet of the Western Ghats.

The film has a simple narrative built around the guilt caused by the infidelity of the protagonist’s newly-wed wife with his imposing supervisor. Caught between them is an officer who feels intensely guilty when the protagonist commits suicide. In this film, Aravindan adopted a simple narrative style—a clear breakaway from his earlier films. Format-wise, he stuck to his meditative style, and his affinity for the oral traditions of rituals and stunning visuals. The star value of Smita Patil did help at the box office. However, as Aravindan had sold the film for a small profit and the box office collections were almost five times the production cost of the film, it made Chidambaram the most popular of his creations.

His next film, Oridathu (Sometime Somewhere, 1987), is almost along the same lines of his earlier film, Thampu. In a way, both Thampu and Oridathu trace their way to Aravindan’s roots—cartoons. The literary characters of the films are caricatures, similar to a cartoon film, though in Oridathu, the plot and its sub-plots portray a village comprised of diverse groups and individuals. It has a loose story about electricity transforming a sleepy village and its age-old life, and how the modern technology affects them. For a change, the director, who was known for his mystical characters and silence, appeared to be filling his film with lively characters. Even a comical, drunken dance by one of the characters, portrayed by Jagannathan, reminds one of the Kavalam play, Avanavan Kadamba (One’s Self is the Hurdle, 1976). Overall, Aravindan appeared to be playing around with the film to reach even those uninitiated to art house films. For the film, he was once again honoured at the national film awards for best director. The state also gave him the best film and director award. Clearly, from an auteur-style, Aravindan was slowly moving towards a more inclusive film-making style.

Little is written and spoken about his other two films Unni (1989), made with students of Harvard University, and Marattam (Masquerade, 1988), which he made based on a play by Kavalam Narayana Panicker. The latter was based on an original story of a Theyyam artist who was being investigated for murder when he was on a self-purification drive to play the role of god. Made for Doordarshan, the film was aired for television audiences. ‘In a tour de force of interpretative brinkmanship, he makes a mockery of cause-effect, subject-object dualisms. The artistic event—Keechaka Vadham, or the killing of Keechaka—breaks out of its formal Kathakali mould to become a tantalising and elusive murder mystery. Keechaka is actually killed, but is it the Kathakali personage or the actor who dons the role who is done to death? Why? And by whom? There are at least three constructs, three versions, each of them as convincing as the rest. At the end of it all, was Keechaka killed in the first place? If these questions remain unanswered, already the process of unravelling the mystery has shifted subtly from a routine investigation to a metaphysical enquiry. Marattam comes like a reaffirmation that Aravindan’s innate artistic vision remains as unfazed and uncompromising as ever’, writes Sasikumar about the film (Kumar 2010). Aravindan attempted to combine elements of the Roshamonic (influence of seeing truth from multiple angle as in Kurosawa film) truth in the situation and his favourite Thanathu theatre style.

His last and best

I consider Vasthuhara (Dispossessed), his last work, as his best feature film in all aspects. Not because it was another story by Aravindan’s favourite writer, C.V. Sreeraman, but because of the way he tried to showcase Malayali-Bengali cultural connections through his characters and their common fate. In a humane way, he showcases the plight of refugees from Bangladesh, and their quest for a new life. He also portrays the entanglement of the Malayalis through politics, modernity, and bonding. Apart from the settlement process of the refugee Bengalis he also peeks into the human tragedy of the involved Malayali characters and their Bengali counterparts. The protagonist Malayali character finds his uncle’s Bengali widow among those seeking salvation for their distressed life in a distant island.

Aravindan’s worldview and his approach to cinema could be seen intensely in his last film. Like all his other films, the caricatures of life around the main characters appear silently, making the sequences lively. As the protagonist digs deeper into the fate of his uncle, and the Bengali family, one can hear a fat man fretting away as he exercises, much to the amusement of the audience as well as the leading character. On another occasion, the fat man tries to get his key from the lodge reception, only for the Malayali owner of the lodge to misunderstand what he says as ‘Ki’ (‘what’ in Bangla). This happens when the protagonist is caught between the tragic story of his uncle’s Bengali family. Finally, he identifies and makes peace with them, only to leave for a distant land with other refugees seeking a new life for themselves. ‘There is no intense drama here. But Aravindan beautifully brings together a group of people in his film, though they are separated by their homeland and language and even culture’, observed veteran film writer Chidananda Dasgupta about the film, which ran for a week in Kolkata’s prestigious Nandan cultural complex (Aravindan 2010:170).

A visionary film maker short of the right 'filmy' idioms

The 11 films by Aravindan, which made him a part of Malayalam film history, come off as cultural icons of the times he lived in. Just as his cartoons were a mirror to the contemporary lives of Malayalis, Aravindan’s films are a cultural exploration of their inner lives as well. Be it the radical, unemployed young protagonist of his first film, or the protagonist of his last, where he tries to bridge the divide separating two families in two distant lands, Aravindan remained a humanist, and an artist who loved creating on caricatures of contemporary life.

His foray into the genre of philosophical films remains, at best, an experiment; though Kanchana Sita, Kummatty, and Esthappan were received well by the connoisseurs and film students. However, he was forced to end his efforts at that genre of films with Pokkuveyil, as they were not supported by equal measure of filmy craft and visualisation. At one level, though he had the vision and a philosopher’s touch, his lack of deep understanding of the film craft did not allow his works to be pushed into the realm of all-time great films. No doubt his films remains a milestone in the growth of film as an art in Kerala.

Aravindan appears to be more comfortable with making contemporary caricatures of his characters, as seen in Thampu, Chidambaram, and Oridathu. He leaves a totally different 'filmy' experience with his first and last films in a simple narrative style, as they both shared the characteristics of definite storylines mixed with intense humanism. ‘Aravindan’s creative mind traversed between, contemporary experiences to mythologies, to legends to history. He revealed a complete cinematic and artistic expression of contradictory as well as multi-levelled experience of both inner and outer meaning of the subjects he handled’, film writer O.K. Johnny, observes in his book (Johnny 2001:44).

‘In film after film, he excavated new experiential terrains, unfolded new connections, transgressed boundaries between genres, forms and styles. In a way, one can also look at his films as creative dialogue between different mediums, of different art forms conversing with each other, probing at and extending boundaries, and creating a new, synergistic aesthetic engagements’, C.S. Venkiteswaran, a senior film writer pointed out, while introducing Aravindan at the Aravindan memorial lecture at the International Film Festival of Kerala in 2017 (Venkiteswaran 2017).

His craft, which evolved with Uttarayanam, and stabilised with Chidambaram, ends in a mastery of his cinematic situations with his last film, Vasthuhara. From his second film onwards, he had an army of FTII graduates as assistants and collaborators, giving his films the distinct look and feel of a visionary humanist painter at work. With his style of script-less shooting, and reliance on artistic and situational intuition, Aravindan was able to raise his films to a cultural event of Kerala, making ripples across India and abroad. However, they always seemed to fall short of being extraordinary works of art for want of the right 'filmy' idioms and style for his vision.

Aravindan was not trained in the film craft, but he had a deep affinity for the medium. As a man of culture, he had a deep interest in painting, theatre, cartoons, and above all, an empathy and love for the suffering of humans. His very personality as a man of Malayali culture gave his works a different look and feel. His films stand out in time, with the imprint of his multi-faceted personality. For the Malayalam film history, divided between the FTII graduates and the non-FTII film makers, Aravindan commanded the respect of a team of FTII graduates as his crew and assistants, once again underlining that it is the individual creative genius alone, which makes a film maker great.

References

Aravindan, G. 2010. Kerala Chalachitra Academy (A Commemorative Book), Published on the occasion of his 75th birthday.

Das Gupta, Chidananda. 'New Directions in Indian Cinema'. Film Quarterly. Vol. 34, No. 1. pp. 32-42.

Dönmez-Colin, Gönül. n.d. ‘Malayalam Cinema from Politics to Poetics’. Kinema. Online at http://www.kinema.uwaterloo.ca/article.php?id=332&feature (26th December 2017).

Johnny, O. K. 2001. ‘Cinemayude Varthamanam.’ About Cinema Issues. Olive, Kozhikode p. 44.

Khanna, Satti. 1981. 'Review: Esthappan by Aravindan, General Pictures'. Film Quarterly. Vol. 35 No. 1, Autumn (pp. 53-56).

Kumar, Shashi. 2010. ‘Aravindan’s Art’. Frontline. 27.1. Online at http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2701/stories/20100115270116000.htm (26th December 2017).

Venkiteswaran, C.S. 2017. ‘G. Aravindan. Always a Contemporary.’ speech at International Film Festival of Kerala 2017, Aravindan memorial lecture, 9th December 2017, Kairali Theatre, Thiruvananthapuram.