Like cinema, remembrance is also an act of love. To remember is to love, and to live as well. To live is to imagine and to create. Imagination and images are the two most important elements of human existence and human civilisation. Without images and memories there will be no love, no history. Without imagination there will be no civilisation.

I was also one of those who came to know G. Aravindan through his famous cartoon serial Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (Small Men and Big World). Like many others, my initiation into the language of cinema was through comic strip serials such as Phantom and Mandrake. Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum however, was distinctly different from those comic strips, with its bold lines and unique composition. Moreover, it narrated the story of a young man named Ramu, in a contemporary context, and was a reflection of what was happening at that time. Like hundreds of others, I too eagerly waited for the newest edition of Mathrubhumi, every week. So, it was with utmost interest that I saw Uttarayanam — Aravindan's first film.

I can still remember the image of the dead face of the father, covered with crawling ants. I still remember dialogues from the film, such as ‘Asking questions is more important than finding answers,’ or ‘There will be a time when the spoken word of the other will be appreciated like music’, etc. I can still remember the day I saw Uttarayanam, at Kavita theatre in Ernakulam. The film touched me deeply, convincing me to study cinema under his guidance. Luckily, Aravindan had come to Cherthala with his team to stage the play Avanavan Kadamba (One’s Self is the Hurdle) It was performed at the grounds of the school where my mother was teaching. So, I asked my mother to speak to Aravind ettan (brother) and convince him to meet me later in Trivandrum. My mother succeeded, which is how I ended up meeting G. Aravindan. I was only eighteen years old at that time, though I had already read a few books on cinema and seen a few classic films. I even kept a notebook where I would write down random thoughts on cinema. Our meeting was rather a silent one. I insisted that he read the random thoughts I’d written on cinema. He kindly obliged my request and read all that I had written. In the end, he suggested that I should consider joining FTII. On his advice, I eventually joined FTII in 1979.

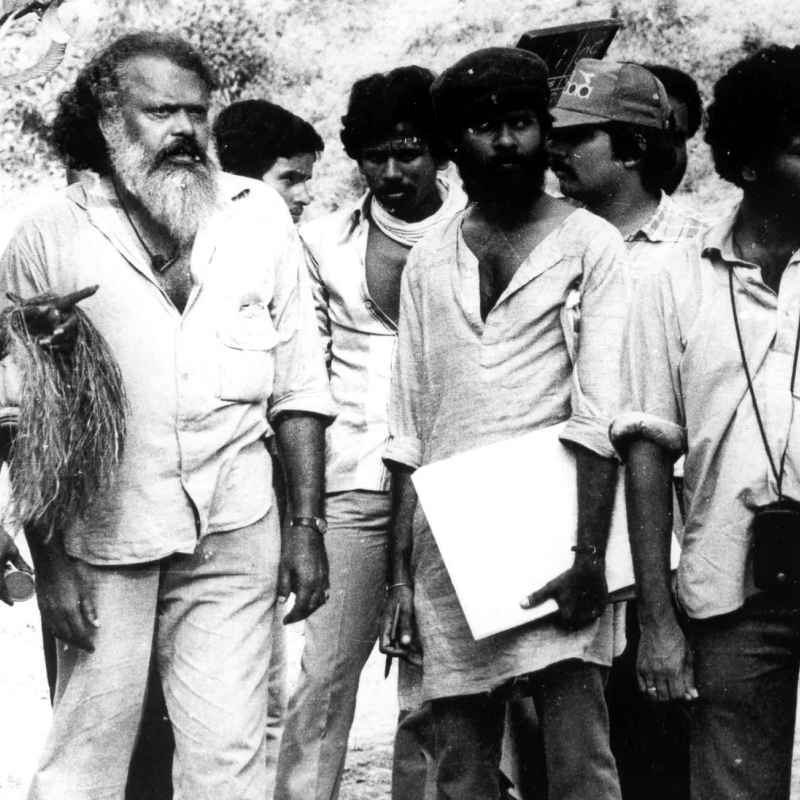

Though I joined the Editing course, I ended up specialising in cinematography. But, at the same time, I wanted to pursue my interest in film direction. I was determined to work with Aravindan as his assistant. But when I made my request, he gently refused it by saying that I have no need to train under him since I already have an understanding of cinema. But I continued my association with Aravindan by doing cinematography for a few of his documentaries, and eventually doing cinematography for his last two films, Unni and Vaasthuhara (The Dispossessed).

He was a great friend with whom one could share all their joys and sorrows. At times, he was like a father figure to me, and would always be prepared to protect me in case a need should arise. In fact, he agreed to direct Unni (it was a project film of Harvard University students) to help all of us, financially. The remuneration from Unni helped me buy a house in Trivandrum. Aravindan is the only producer who paid me extra (double than what was agreed) when he made some profit from Chidambaram.

G. Aravindan lived his life and created multi-faceted works of art based on the principles of love and sacrifice. He once said, ‘If there is any aim for art, it is to create a compassionate and strong humanity.’ Yes, from Uttarayanam (Throne of Capricorn) to Vasthuhara, all his films made us remember the need for compassion and love. Like any other great artistic creation, G. Aravindan’s films also spoke to us about the absence of a loving, compassionate society and the need for love.

On a personal level, Aravindettan is the one who taught me the meaning of true spirituality. He, through his life and creations, showed me the interconnectedness of all things. He showed me the interconnectedness of an individual to another, and an individual to nature. By observing his life, I too learned how to be compassionate and loving towards fellow human beings. His cinema also taught me to be big-hearted towards men with tiny hearts.

Are these not the two fundamental principles of art itself? Asking questions [to be active] and trying to evoke the essence of beauty. Asking questions about the essence of hope and harmony, which can create this beauty? It is no wonder that Dostoyevsky once said 'Beauty will save the world'.

It is not my intention to say that an artist’s work should show the beautiful. How can one watch refugees fleeing from a war in Vaasthuhara and consider it beautiful? How can the agony written on the faces of two great artists, Gopi and Smita Patil, in the climax of Chidambaram be termed as beautiful? How can the dispossessed wailing of a displaced humanity at the end of Vaasthuhara be termed beautiful? This essence of beauty lies in the final moments of the experience that the work of art evokes. At that moment of absolution, a work of art reveals the beauty of creation and becomes a ‘Mirror of Love’ like the ‘Mirror’ of Sri Narayana Guru.

I have always thought that any great work of art, is a ‘mirror of love’ and Aravindettan’s films have always stood out for me as fine examples of this idea. In my experience, I have seen more spirituality in a cinema hall than in a church. As Andrei Tarkovsky said, cinema or any other work of art, is probably the evidence of a ‘creator’. Aravindettan’s cinema also evoked this higher connection to the Divine.

It is not my intention to dwell on the aesthetics of Aravindettan’s cinema. Many critics have written eloquently about his films. From my experience of seeing 100 classic films at a single go at the 1995 Soorya Film Festival, G. Aravindan’s films stand among the best cinematic creations of the world. He is our most poetic, original, and truly experimental filmmaker. His cinematic genius lies in its capacity for simplicity. Like a Zen monk, he is a master of the principle of minimalism. His cinema always tried to chisel out the inessential. Like a haiku, his cinema reveals the true essence of nature and people. It is a paradox that we often tend to forget that the most long-lasting creations of human civilisation, like the pyramids, were based on the principle of simplicity.

Let me now recount an incident. I was shooting a documentary on Bharatanatyam with him. It was to be a three-day shoot of just clouds, wind, grass, light, etc., and we were going to Ponmudi to shoot the jungle in different moods. I reached his home early in the morning at 5 am. In the car, he gave me a paper cutting and said, ‘Sunny you must read this interview.’ I read the clipping using the backseat light of his black Ambassador. I managed to make out the name of Vilmos Zigmond. One of the finest cameramen of Hollywood! I had no idea why Aravindettan had given me a Hollywood cameraman’s interview to read! Well, after the shoot, I went back and read the interview in its entirety. One line from that interview became my guiding principle in cinematography. Vilmos Zigmond says, ‘No image can be more beautiful than its meaning.’

I do hope that one day, I will be able to make a film worthy of a student of G. Aravindan and pay my respectful homage to the great master.