In-depth analysis of the Cosmography of the Chausathi Yogini temple, Hirapur

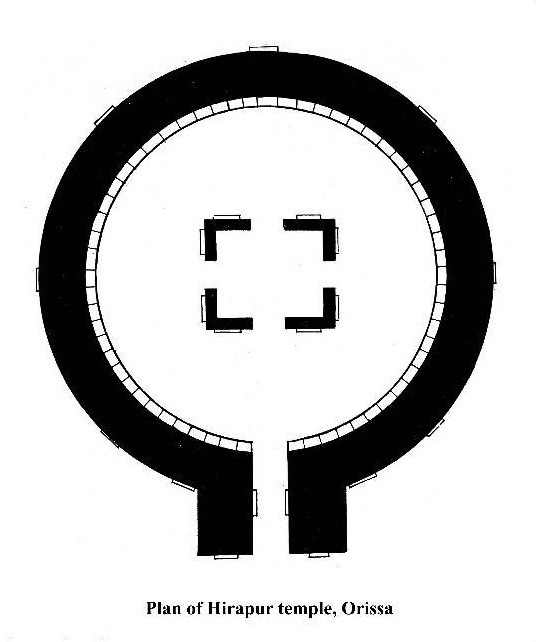

There are 11 extant Chausath Yogini temples found across India out of which two are in Odisha, five in Madhya Pradesh, three in Uttar Pradesh and one in Tamil Nadu. The most prominent ones are Hirapur, Ranipur Jharial, Khajuraho, Bhedaghat, Mitauli, Dudahi, and Rikhiyan. Yogini images have been discovered from Shahdol, Hinglajgadh, Lokhari and Naresar. It is a well-known fact that the yogini temples found in the Indian subcontinent are hypaethral; that is, they are structures without roof or superstructures. The temples are also peculiar for their circular ground plan (rectangular ground plans have only been found in Khajuraho, Badoh and Rikhiyan). There have been different interpretations for the circular plan and roofless structure. One of the most prominent ones being that the temple plan resembles the circular platform on which a Siva linga resides. The keyhole-like structure is the smallest of all Chausath Yogini temples. The open-air circular temple has been attributed to 9th–10th century AD, and is considered one of the earliest of all-extant Chausath Yogini temples found across India. Despite its historic importance, this temple remains understudied.

The period between the 9th–10th centuries is widely believed to be one of correction and amendment in Hindu tantra from ritualistic excesses to moderation. Here the transition does not mean a sudden change, but a steady process by which a former tradition not only altered but also continued and acquired newer connotations in a different socio-religious context that gave way to widespread architectural and sculptural proliferation. Hirapur Yoginis also emerged at the cusp of this widespread tantric monumental proliferation. Each yogini temple is symptomatic of regional variations which reflect the unique traditions of the area where it is located (Dehejia 1986: 94). There are certain aspects of the temples that are common. Most of the yogini temples are located in remote areas. For example, the temple of Ranipur Jharial is located several miles away from the nearest town (1986: 103). The temple of Hirapur is extremely isolated, with the only way to access it being through one small dirt lane (Gadon 2002: 33).

This temple is located between Bhubaneshwar and Puri—Ekamrakshetra and Prurshottamakshetra, both known to be prolific centres of tantrism in their times—in the Hirapur village of Khurda district, Odisha. The temple is built of coarse sandstone blocks with laterite in its foundation. The yoginis are carved out of fine-grained grey chlorite. The inner walls of the temples have 64 niches with 60 yoginis still in place. When it comes to Hirapur Chausathi Yogini Temple, there is neither any epigraphical nor any textual evidence giving the exact date of the establishment of the temple. According to an 11th century Oriya text Ekamracandrika[1], the temple at Hirapur was one of the Shakti pithas of Ekamra (Bhubaneshwar), which sounds like the interpretation of a non-follower. There isn’t any reliable information about its early history giving any insight into the purpose of this particular temple. Some of the academic literature produced in Odisha point to the possibility that this temple might have been constructed by Queen Hira of Bhaumakara dynasty and the village takes its name from the queen’s (Mahapatra 1953: 25). However, any evidence connecting this temple and the ruling Bhaumakaras hasn’t been available. Most prominent among the temple building activity of the Bhaumakara was the Vaital Deul Temple of the late 8th century in Bhubaneshwar. The barrel-vaulted Vaital Deul is a Kapalika shrine. A fearsome Camunda as the godhead is enshrined in the temple along with seven Matrakas—Brahmani, Mahesvari, Kaumari, Vaisnavi, Varahi, Indrani and Shivaduti. Also accompanying them are Virabhadra, Ganesa, Kubera, Varaha, Nagaraja and two skeletal bhairavas. Though this hasn’t been proven substantially by the scholars, it cannot be denied that some of the prominent tantric temples of Odisha were constructed during the reign of Bhaumakaras. The Bhaumakaras who came to power in the 8th century AD after replacing the Sailodbhavas, ruled over all of Odisha except the north-western region of Dakshin Kosala.

In the words of Shaman Hatley (2007: 18), ‘with the increasing significance of Yoginis in the Purana corpus, the Yogini temples in fact appear to mark the entry of these deities into a wider religious domain, beyond the confines of the esoteric tradition - to the point that their ritual mandalas are translated into monumental circular temples.’ The temple plan resembles a yoni patt on which a Siva-linga rests. The temple rises to a height of 27.3 metres from above the ground and a diameter of 30 feet. The temple is made up of coarse sandstone with a base made of laterite. The temple though of a much lesser height than the monumental temples of Bhubaneswar, has a pabhaga and jangha. The pabhaga is devoid of any decoration. The outer wall of the jangha consists of nine unadorned niches containing the nine ferocious female guardians called katyayanis. The lowly built entrance to the temple is guarded by two dvarapalas. Inside the temple is a central shrine with eight niches, out of which four are occupied by yoginis Ajita, Suryaputri, Vayuvina (one empty niche dedicated to now lost image of Yogini Sarvamangala); the other four niches are occupied by the four bhairavas. All the yogini images are finely carved and are standing in varied poses. Yoginis are beautiful women with rounded breasts, slender waist and broad hips wearing a diaphanous skirt held in position by a jewelled girdle placed low on the hips. They are ornamented with necklaces and garlands, with armlets, bangles, anklets, earrings and elaborate coiffures. Unlike the much elaborate and monumental Chausath Yogini temples of Ranipur Jharial, Mitauli and Bhedaghat, the yoginis here occupy smaller niches with their own roofs and base mouldings. It is considered the most beautiful of all the Chausath Yogini temples because of the inherent simplicity with which the temple has been constructed.

The use of chlorite as the material for sculpting the yoginis has imparted a distinct beauty to the yogini sculptures. The artful chiselling of each element ranging from the distinct hairstyles and jewellery to the smooth, glistening skin has given way to a unique visual vocabulary. Some of these delicately-carved yoginis have a smile on their faces which adds to their enigma, while some of the others are grotesque. What is evident from the pantheon of Chausath Yogini is that female divinisation lies at the crux of it, and the presence of these yoginis comprises one of the most historically significant facet of their cult.

There are various lesser-known theories which present the architecture of the Hirapur Chausathi Yogini Temple in a different light. One of them being that the cosmological programme of the temple is akin to a mandala, where strategically placed yoginis like Varahi, Kaumari, Mahamaya and Chamunda denote various energies within a mandala. The temple seems to follow a mandala plan in a way that concentric circles are formed when Siva at the centre inside the inner sanctum is roundly surrounded by four yoginis and four bhairavas. The next circle is formed by the nine katyayanis and two dvarapalas. It is the only yogini temple which has sculptures on its outer wall. There are nine feminine images, identified as the ferocious katyayanis surrounding the exterior walls along with two male guards flanking the passage; these dvarpalas have been identified as bhairavas. Inside the enclosure, there is a rectangular central shrine housing Ekapadabhairava (also known as Jhamkarabhairava) (Donaldson 1985: 1053).

Similarly, well-known Indologist Prof. Henrich von Stietencron (2013: 70-83) has equated these temples to kalachakras or the wheels of time. According to him, the temple being perfectly circular and with the entrance facing east, the architecture of these temples was such which helped the priests to calculate solar and lunar time. He further elaborates his hypothesis by looking at the square-shaped chandi mandapa located at the centre of the temple. The chandi mandapa as mentioned above houses four bhairava images, but according to architectural texts there used to be a standing image of Martanda Bhairava at the centre of the square pavilion. There could be certain truth to this theory as a dancing Martand Bhairava image has been found from another Chausath Yogini shrine from Ranipur Jharial in Balangir district of western Odisha. ‘Martanda’ is one of the names of Sun god, and ‘Bhairava’ is a ferocious form of Siva who is associated with yoginis—this points towards a syncretic solar-cum-saiva tantric deity. The solar aspect of this temple could also be ascertained from the four faces of Martand Bhairava representing four directions. The cosmological arrangement of the temple shows Sun as the ruler over space and time, as it is the sun which is the representative of the solar year and the stable centre around which all the movement circulates.

Hence, it is believed that keeping in line with the architectural and iconographic programme of the Chausath Yogini temples a four-faced Martanda Bhairava stood in the middle of the circle of merry-making yoginis, as Miranda Shaw (1994: 81) describes them: ‘yogini’s gathered at feasts to play cymbals, bells, and tambourines and danced within a halo of light and a cloud of incense. Within this nocturnal congregation, a circle of yoginis feasted, performed rituals, taught, and inspired one another. They sang songs of realization regaling one another with spontaneous songs of deep spiritual insight.’

The cult of Chausath Yoginis was one of the most esoteric cults in medieval India which vanished as suddenly as it emerged in the Indic religious landscape, leaving very little trace of its existence. A study of its architecture and cosmographic arrangement could perhaps lead a way to uncover its several layers of symbolism.

References

Dehejia, V. 1986. Yoginī Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition. New Delhi: National Museum.

Donaldson, Thomas E. 1985. Hindu Temple Art of Orissa 3 vols. Leiden: Brill.

Gadon, Elinor. ‘Probing the Mysteries of the Hirapur Yoginis’. In ReVision Vol. 25, no. 1 (2002): 33-41.

Shaw, Miranda. 1994. Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Mahapatra, K. N. 1953. 'A Note on the Hypaethral Temple of Sixty-four Yoginis at Hirapur,’ Orissa Historical Research Journal II: 23–40; reprinted in H. K. Mahtab, ed., Orissa Historical Research Journal, Special Volume, 1982.

Hatley, Shaman. 2007. ‘The Brahmayamalatantra and Early Saiva Cult of Yoginis’. Unpublished PhD. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Stietencron, Henrich von. 2013. ‘Cosmographic buildings of India: The circles of the yogini,’ Yogini in South Asia: Interdisciplinary Approaches (Routledge Studies in Asian Religion and Philosophy), ed. István Keul, pp. 70-83. London: Routledge.

Further readings

Hatley, Shaman. ‘Matr to Yogini: Continuity and Transformations in the cult of the Mother Goddesses,’ in Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond, edited by István Keul, pp. 99–129, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2012.

Mishra, P.B. Orissa under the Bhauma Kings. Calcutta: Vishwamitra Press, 1934.

Panigrahi, K. C. Archaeological Remains at Bhubaneswar. Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1961.

Sharma, Rajkumar. The Temple of Chaunsatha-yogini at Bheraghat. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1978.