Phanek is a sarong worn by the Meitei people of Manipur as part of their traditional attire. It has distinct weaving patterns and motifs depending on the community wearing it, its history, regional specificity and traditions.

Lower garments like phanek are found across India’s Northeast, such as mekhla in Assam and puan in Mizoram. Each tribe’s ethnic heritage can be gleaned from the colours and weaves of these garments which serve as markers of their cultural identity. Even among the various tribes of Manipur, there are distinct names and patterns for the wraparound skirt. For instance, it is known as ponve amongst Kukis, pheisoi among Kabuis/Rongmeis, kashan among Tankhuls, lungvin among Anals, to name a few.

In Manipur, the phanek is revered as a sacred garment, adorned with ancestral motifs derived from indigenous history, flora and fauna, and creation myths. It is generally woven by women—though recently there have been male phanek weavers as well—and exhibits the community’s aesthetic vision through its artistic skills. As an object of women’s attire, it has emerged as a symbol of femininity and female agency in the state. Such constructions also simultaneously evoke the contradictory position of female autonomy as well as gender bias.

Sacred yet Sinister

The phanek occupies a paradoxical position in the Meitei society where it is venerated but is also considered a taboo. It symbolises the conventional virtues of femininity which are hinged upon qualities of compassion and nurture—both life-giving and life-affirming. A telling example of this is the oft-repeated story of the Sugnu queen who used the phanek to overturn death sentences.

When Manipur was an independent kingdom, there was a separate court of justice for women, known as pacha court, where the queen conducted the trials.[1] In Sugnu (a town in Kakching district of Manipur), where offenders and convicts were sent to be executed, the wife of Sugnu lakpa (chief of Sugnu) had the power to convert a death sentence to a life sentence.[2] If she covered the guilty person with a phanek, it was a symbolic gesture of giving them a fresh start and a new life.

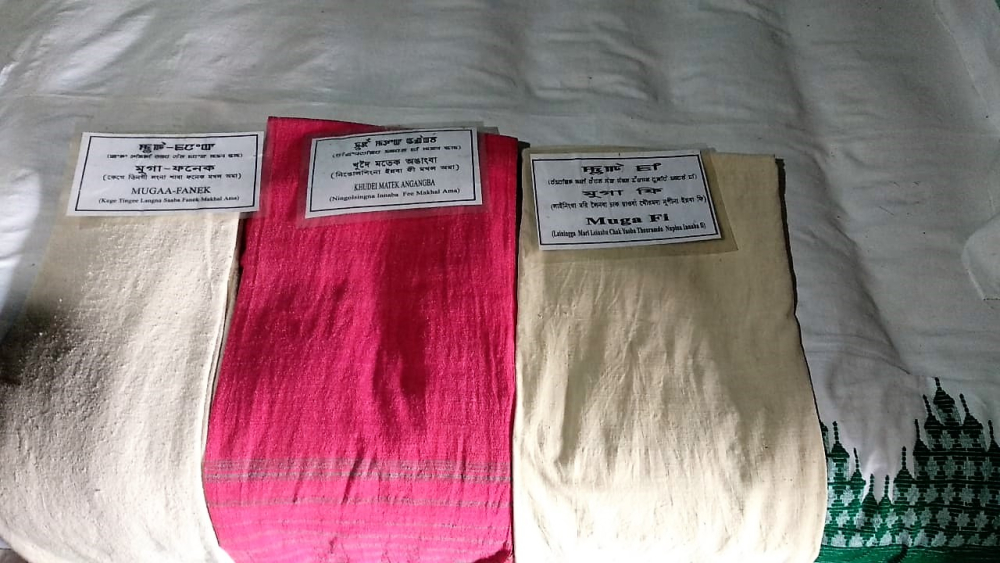

A muga silk (a type of silk indigenous to the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam and the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas) phanek was also a common attire for sacred ceremonies such as the ear-piercing ceremony of a child or community feasts. Different kinds of phanek are worn as daily wear, formalwear, as a traditional dance costume and at rituals, each charged with deep cultural sentiments. (Figs 1 and 2) The art of weaving was considered a mandatory skill for young girls and women, and was useful for supplementing household income. Weaving also provided women relative economic freedom and was passed down generations as a cultural skill.

Several beliefs and practices associated with the phanek also present a perplexing combination of fear and distrust. It was believed that one should not wash the phanek with other clothes, especially men’s clothes. Hanging the washed phanek in the open courtyard was also discouraged, since a man might walk under it or touch it. Such beliefs imply that the phanek was considered ominous for men and touching it was thought to bring misfortune, even death, to them.

Take, for instance, ‘phanek bashing’ which is a practice of hitting men with a phanek to inflict humiliation and degradation on them. It is considered a dreaded punishment for men which ‘emasculates’ them and, during agitations, it is also extended to policemen and military forces which are identified as masculine sites of power and oppression. The act of being touched by a phanek, more so by an angry woman wielding the phanek, is perceived as a deliberate gesture that feminises men, stripping them off their masculine potency. Phanek bashing lends the phanek with a supernatural quality capable of communicating the woman’s anguish when language falls short. But it reproduces patriarchal hierarchies by its inherent reliance on the trope of the feminine as undesirable or inferior.

Such beliefs underline the liminal space occupied by the phanek between empowerment and punishment founded upon traditional roles of gender. The contrasting symbology of the phanek between both its sacred and sinister aspects affirm conventional gendered roles. The phanek, therefore, becomes the medium of navigating societal aspirations and imagination. Through the beliefs and practices associated with the phanek, one can note the dual connotations of promoting gender hierarchies as well as circumventing them but never quite transcending them.

Kumam Davidson, teacher at Moirang Multipurpose Higher Secondary School, Manipur, and researcher of literature, notes, ‘The phanek is such an integral, indigenous part of the local ethos, the word feminism is not the first thing that one comes to associate with it. Anything about the phanek ultimately becomes a discourse and yet, it is not talked about, or understood enough.’ The phanek does not have to be necessarily caught in a binary relationship between reinforcement and subversion of patriarchy though it is more pertinent to view it as an instrument of negotiation between both.

Phanek as a Symbol of Protest

Historically, women in Manipur have played a crucial role in protests and demanding justice. In popular discourse, therefore, the phanek is an iconic representation of resistance and agitation. This is reflected across the collective memory and representation of defining moments in Manipur’s history, through paintings, sculptures and curated photographs. The power of the Meitei women to mobilise and organise mass action is attributed to their high social and economic status. Women are dominant in the market economy, controlling the supply chain for food, textiles and allied sectors.

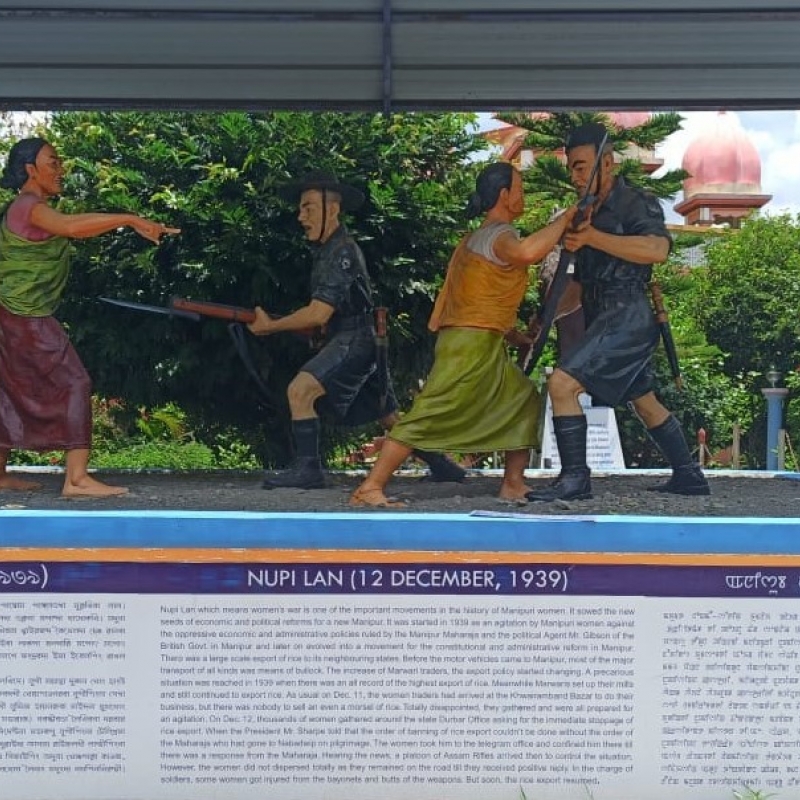

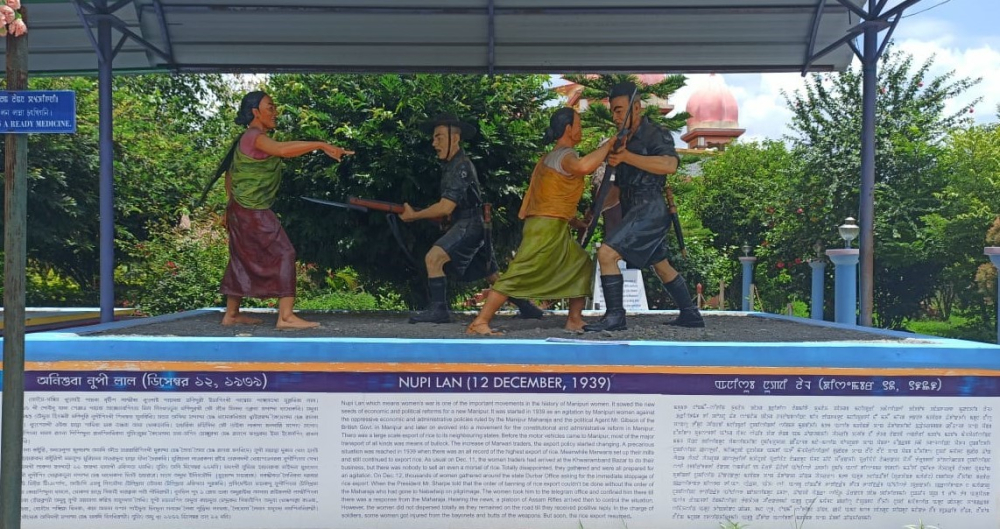

The nupi lans (women’s wars) are famous instances of phanek-clad Meitei women proactively leading the call for demonstrations. Nupi Lan I (1904) was a movement to defy the orders of the British political agent in Manipur. When the political agent tried to reintroduce lalup (a system of forced labour) which had been abolished earlier, the women rose up in rebellion to protect their men. Lalup is regarded as a form of tax, in which all adult males in Manipur valley had to provide labour to the state for 10 days out of every 40 days.[3] The political agent’s order required men to go to Kabow valley (now in Myanmar) to collect timber and contribute labour for the reconstruction of the assistant political agent’s bungalow that had been destroyed in suspected arson.[4]

Nupi Lan II (1939) was sparked by the discriminatory economic policies of Maharaj Churachand Singh, who was acting upon the orders of the British political agent Christopher Gimson. After the British occupation of Manipur in 1891, the political agent alone was empowered to authorise the export of rice and in 1912, and this export was delegated to a trading company, which resulted in an increase in the price of rice and possibility of widespread hunger.[5] Nupi Lan II is immortalised in popular culture of the state with images of phanek-wearing women resisting gun-wielding British officers. (Fig. 3) Many of these bold Meitei women lost their lives in the rebellion which continued for months. This movement was also a watershed moment in Manipur’s history as a catalyst in the demand for political and democratic reforms.

The visual representations of these movements present the ubiquitous phanek-clad women charging ahead, confronting men and institutions of power. The phanek, therefore, is also emblematic of assertion of power. Even before the nupi lans, there were records of women mobilising together and demanding social justice. This belief is further utilised and amplified in the use of phaneks to impose restrictions. (Fig. 4)

Another prominent instance of the phanek’s symbolic power is the nude demonstration by 12 imas (mothers) in front of Kangla Fort in 2004, to express grief and anguish over the rape and murder of political activist Thangjam Manorama by the Seventeenth Assam Rifles. If the phanek is emblematic of power, traditions and modesty, the disrobing of the phanek signals the disempowerment of women and civil society at large at the hands of military excesses and state transgressions. In this protest, the project of nationalism, which uses the trope of the mother and motherland that needs protection by righteous sons of the soil, is inverted effectively.[6] Here, it is the mothers who come to the fore, incited by grief and angst, and reclaim political space to protect civil society from coercive state action. In iconic images of the movement, they hold up a banner that states, ‘Indian army rape us’, taunting the military and its rhetoric of protection. In this context, removing the phanek can be interpreted as confronting the values of protection and defence that is enshrined in the discourse of a paternalist state.[7]

The phanek’s symbolic significance is embedded within such movements that have strived to agitate and resist oppressive measures. When there are blockades or general strikes, the roads are blocked by hanging phaneks near the street to display the call for protest. As a garment that symbolises femininity and women’s agency, the perception of unease with the phanek is perhaps a reflection of the unease with women’s agency in general.

Historically, women’s bodies have been the locus of defining, contesting and documenting culture. The incongruous practices and beliefs associated with the phanek signifies these apprehensions of culture that are articulated through the fraught relationship between national identity and gender.

Negotiating Women’s Agency

Meitei women have been credited for spearheading grassroots activism in Meitei society, and the phanek is a symbol of this political consciousness. The use of the archetypal ima (mother) figure in such movements is a persuasive tool but it limits the scope of work on gender issues.[8] Deified by the principles of sacrifice, protection, and physical and emotional labour, such symbolism presumes women to be mothers or potential mothers, essentialising women to a biological function. Yet feminist politics has also long acknowledged that ‘there can be no feminist position that is not in some way or other involved in patriarchal power relations.’[9] The phanek’s symbolism is implicated in patriarchal social constructions since it essentialises gender roles. Its use in social activism reveals the dilemma between intellectual rigour that disapproves of essentialism and universalism, and political struggles that must find ways to carve out avenues of power. Local specificities and contextual experience influence the degree to which women conform or flout patriarchal models and determines the efficacy of these movements. In the case of Manipur, the emotive appeal of the Meitei mother has been successful in challenging state aggressions but remains controversial in the ways it achieves this.

It is no surprise then that the phanek, perceived as an artefact of culture and heritage, is an attire that evokes cultural pride. It consequently acts as a lens to define morality and immorality. The anxiety of losing or ‘diluting’ indigenous culture, already relegated to margins in the national consciousness in a rapidly globalising world, remains an overarching concern while discussing the phanek’s pivotal role in upholding culture. Often, it is framed through a moralising gaze and the subjects are primarily women, queer and other ethnic minorities. Thus, phanek-clad women are called to carry the mantle of dignity and uphold Meitei culture while they are simultaneously also seen as the biggest threat to this culture as they are considered prone to influence of external (non-Meitei) culture. The phanek-wearing woman signals moral superiority and virtuous purity, others, by default, are rendered morally dubious. Such beliefs can be seen in some groups that call for schoolgirls to mandatorily wear phaneks and banning nupi manbi (transwomen) from wearing phaneks in public places, defying which death threats are issued to them as they are considered to be ‘corrupting’ Meitei culture by cross-dressing. These acts of moral policing have been heavily criticised for moral gatekeeping to censure, chastise or exclude those who do not conform or align with the patriarchal notion of culture.

The phanek, therefore, encompasses a tense juxtaposition of seemingly antithetical ideas of the sacred and profane, empowerment and disempowerment, activism and modest restraint, all negotiated upon the body of the woman. While celebrating the pride and heritage of the women who agitated for reforms and social justice, it is also essential to meditate upon the ways in which women are forced to navigate biases in the domestic, social, economic and political sphere. Further, the articulation of this symbol in purely heterosexual terminology presupposes only heteronormative possibilities, thereby concealing or negating the pluralities of gender identity assertion. A critical appreciation of the phanek’s symbology, hence, allows one to acknowledge the unique evolution of grassroots activism and women’s role in spurring reforms, while liberating the attire from its moral connotations.

[2] Brara, ‘Performance’

[3] Lamabam, Makers of Indian Literature, 6.

[4] Parratt and Parratt, ‘The Second 'Women's War' and the Emergence of Democratic Government in Manipur,’ 906.

[5] Ibid., 909.

[6] Ray, ‘Political Motherhood and a Spectacular Resistance.’

[7] Bora, ‘Between the Human, the Citizen and the Tribal.’

[8] Soibam, ‘From the Shackles of Tradition’ 223.

[9] Grosz, ‘Sexual Difference and the Problem of Essentialism.’

Bibliography

Bora, Papori. ‘Between the Human, the Citizen and the Tribal.’ In International Feminist Journal of Politics 12 (2010): 341–360.

Brara, Vijayalakshmi N. ‘Performance: The Gendered Space in Manipur.’ In The Peripheral Centre: Voices from India’s Northeast, edited by Preeti Gill. New Delhi: Zubaan Publications, 2013.

Brown, R (F.R.C.S.E.). Statistical Account of the native state of Manipur and the hill territory under its rule. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1873.

Grosz, Elizabeth. ‘Sexual Difference and the Problem of Essentialism.’ In Inscriptions 5 (1989).

Parratt, John, and Saroj N. Arambam Parratt. ‘The Second “Women's War” and the Emergence of Democratic Government in Manipur.’ Modern Asian Studies 35, no. 4 (Oct, 2001): 905–919.

Lamabam, Damodar Singh. ‘Makers of Indian Literature: L. Kamal Singh.’ New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2000.

Ray, Panchali. ‘Political motherhood and a spectacular resistance: (Re) examining the Kangla Fort Protest, Manipur.’ In South Asian History and Culture 9, no. 4 (October 2018): 435–448.

Sharma, Ditilekha. Nations, Communities, Conflict and Queer Lives. Delhi: Zubaan Publications in collaboration with Sasakawa Peace Foundation, 2019.

Soibam, Haripriya. ‘From the Shackles of Tradition: Motherhood and Women’s agitation in Manipur.’ In Geographies of Difference: Exploration in Northeast Indian Studies, edited by Mélanie Vandenhelsken, Meenaxi Barkataki-Ruscheweyh, Bengt G. Karlsson, 215–232. London: Routledge, 2018.

Yambem, Sanamani. ‘Nupi Lan: Manipur Women's Agitation 1939.’ In Economic and Political Weekly 11, no. 8 (Feb 21, 1976): 325–331.