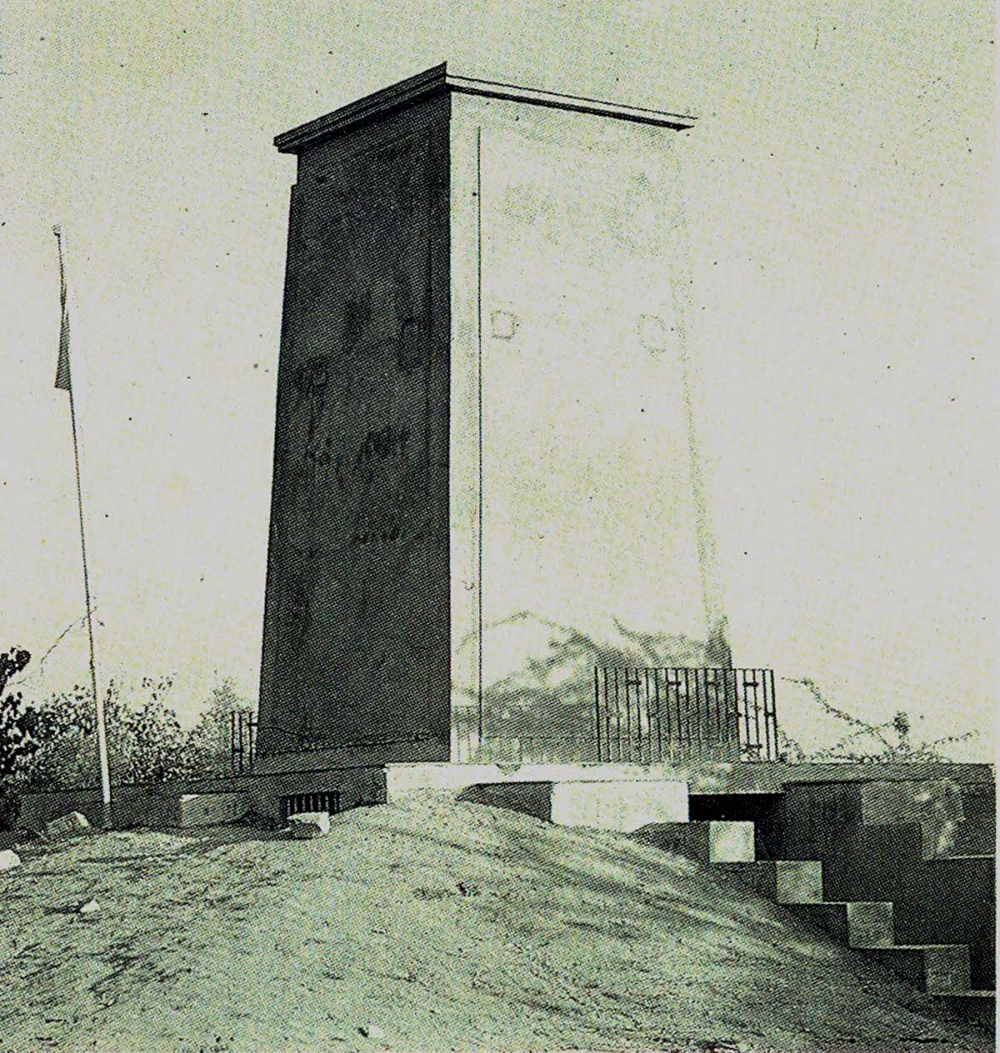

Long before environmentalism became a buzzword, 363 members of Rajasthan’s Bishnoi community, led by the fearless Amrita Devi, sacrificed their lives to save the Khejri tree. Sahapedia trains the spotlight on the significance of the Khejarli Massacre and how it inspired another environmental movement—the Chipko Andolan in 1973. (Photo Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

September 11 signifies a very important landmark in the history of India’s environmental movement.[1] It’s said on this day, back in 1730, in a tiny desert village near Jodhpur, 363 Bishnoi people led by a brave woman resisted the cutting down of trees by the king’s men, preferring instead to lay down their own lives rather than allow the desecration of their environment. In 2013, the Department of Environment and Forests declared September 11 as National Forest Martyrs Day. This saga of supreme sacrifice has had a cascading effect in terms of more recent environmental movements across India, notably the Chipko Andolan. But before we get to the story, we need to understand the Bishnois’ connection with the environment.

The Arid Thar

Over 60 per cent of the Great Indian Desert (Thar Desert) lies in Rajasthan.[2] With precipitation annually fluctuating widely, the terrain is generally infertile. Summer temperature soars to 500C bringing with it swirling dust-laden winds, often blowing at velocities of 140–150 km per hour. Amid a fragile scrubby vegetation, trees are few and far between—the most important being Khejri (Prosopis cineraria) because of its many benefits. Blackbucks and chinkara gazelles are found here along with partridges and quails.

Related | Khejri: A Wonder Tree of the Thar

This inhospitable terrain is also home to the Bishnois, identifiable by their distinct dress style. Traditionally, the men wear white, and the women are attired in ghagra-cholis and veils with particular patterns of red and yellow. The women also wear uniquely characteristic half-moon-shaped nose rings that cover their mouths. They are followers of Guru Jambheshwar, a fifteenth-century seer, whose 29 commandments define their ethos.[3],[4] The word ‘Bishnoi’ itself is derived from bis (twenty) and noi (nine), and thus they are the ‘twenty-niners’. Seven of these commandments teach good social behaviour, 10 address personal hygiene and health practices, four provide instruction for daily worship, and eight are related to conserving and protecting animals and trees and encouraging good animal husbandry. The last-mentioned are the principles that enable them to live harmoniously and comfortably within this inhospitable terrain. A photograph of a woman breastfeeding a blackbuck along with her child went viral in 2019. In fact, Bishnois spare no effort in protecting trees and wild animals. No wonder then that Bishnoi villages are greener, and it is a common sight to find herds of deer and nilgai moving freely.[5]

The Sacred Khejri

The Khejri tree holds a special place in their lives, and cutting down or lopping its branches is taboo. This small evergreen tree has been hailed as the lifeline of the Thar desert.[6] It is a source of shade; its leaves provide fodder to camels, goats, cattle and other animals; its pods are edible and the wood is used as fuel; its roots fix atmospheric nitrogen, making the soil fertile. The khejri is, therefore, invaluable to desert economy and ecology. Revered as shami since Vedic period, the tree features prominently in both the Ramayana and Mahabharata.[7]

The Great Sacrifice

About 18 km from Jodhpur is the small Khejarli village. Like other Bishnoi villages, this one, too, is green and especially rich in khejri trees. It was the morning of September 11, 1730. The village was quiet, the menfolk having gone to the field. Amrita Devi was simultaneously attending to household chores and tending to her three daughters. Suddenly, the peace and tranquility were shattered by hoof beats of horses. Strange men with large axes descended on the village. Amrita Devi rushed out of her house—as did other villagers—with her daughters in tow to see what the excitement was all about. She learnt that these were the king’s men, with the mission to cut down and carry off khejri trees to Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur. Maharaja Abhay Singh had decided to build a new palace and was in need of wood to keep the kilns going for construction material.

It was common practice then to burn lime in a kiln at very high temperature to obtain quicklime which, when mixed with sand and water, would become mortar used to bind and hold together stones and bricks for construction. To keep the kiln going, they needed plenty of wood. This posse had reached Khejarli for an assured supply.

Also read | The Bishnois of Western Rajasthan

Since cutting or injuring trees, especially khejri, is against Bishnoi dharma, Amrita Devi remonstrated with the men, but they were unmoved. She then hugged a tree and declared that even if she sacrificed her life to save just one tree, it would be a good bargain. The unyielding men nonchalantly chopped through her body to cut the tree. Her three daughters, though utterly shocked to see their mother’s severed head, followed in her footsteps bravely, hugging trees and meeting the same end. This made no impression on the royal party, and they continued their task with renewed vigour. The news spread like wildfire and Bishnois of 83 villages gathered at Khejarli. They held council and decided that for every living tree to be cut, one Bishnoi volunteer would sacrifice her or his life. In all, 363 Bishnois from 49 villages became martyrs that day. The very soil of Khejarli turned red with their blood.

When the king heard the dreadful news, he put an end to the felling of trees. Honouring the courage of the Bishnois, he apologised to the community, and issued a decree engraved on a copper plate prohibiting forever the cutting of trees and hunting of animals within and near Bishnoi villages. That protection is still valid today, and Bishnois continue to guard their biodiversity fiercely.

The First Environmentalists

The Khejarli sacrifice was characterised by total non-violence, or ahimsa, on the part of the Bishnois who stood up to perform what they considered their bounden duty. For them, every plant or animal is a living being just as humans, and hence deserves to be protected.[8],[9] This served them well as it fosters a better relationship between human beings, their environment, their religious beliefs and each other, allowing all to live harmoniously. Today experts call this ‘sustainability’, and have labelled Bishnois as ‘India’s first environmentalists’. Yet, within their community it is simply understood to be their dharma.[10]

Nearly 230 years after it happened, the Khejarli story inspired another environmental movement—the Chipko Andolan (1973) in the Tehri-Garhwal Himalaya. This, in turn, spawned the Jungle Bachao Andolan (1982) in Bihar and Jharkhand, the Appiko Chaluvali (1983) in the Western Ghats of Karnataka, and other similar protests. All these were aimed at preserving and protecting the natural environment and resulted in changing public policies. The ‘tree-hugging’ tactic of the Chipko Andolan and its messages gained popularity in many countries beyond India’s borders, leading to protests in Switzerland, Japan, Malaysia, The Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand.[11]

Surely, Amrita Devi would have approved.

This content has been created as part of a project partnered with Royal Rajasthan Foundation, the social impact arm of Rajasthan Royals, to document the cultural heritage of the state of Rajasthan.

This article was also published on FeminisminIndia.com.

Notes

[1] According to some scholars, this incident took place on September 9, 1730; P. Jain. Dharma and Ecology of Hindu Communities: Sustenance and Sustainability (Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2011).

[2] The rest of it extends into Gujarat, Punjab and Haryana. See: J. Arora, S. Goyal, and K.G. Ramawat, ‘Biodiversity, Biology and Conservation of Medicinal Plants of the Thar Desert,’ in Desert Plants, ed K. Ramawat (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2010), 3–36. Accessed August 25, 2020,https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02550-1_1 .

[3] A. Reichert, ‘Sacred Trees, Sacred Deer, Sacred Duty to Protect: Exploring Relationships between Humans and Nonhumans in the Bishnoi Community’ (Thesis submitted for the MA degree to University of Ottawa, 2015). Accessed July 12, 2020, DOI: 10.20381/RUOR-4132. Corpus ID: 131184484. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Sacred-Trees%2C-Sacred-Deer%2C-Sacred-Duty-to-Protect%3A-Reichert/79ee484cf216846f41d73244409eac2eb6296fdd.

[4] Bikku, ‘Religion and ecological sustainability among the Bishnois of Western Rajasthan,’ in Issues and Perspectives in Anthropology, ed. R. Sinha (Jaipur: Rawat Publications, 2019), 45–68. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338412559_4_Religion_and_Ecological_Sustainability_among_the_Bishnois_of_Western_Rajasthan_Bikku

[5] Reichert, ‘Sacred Trees, Sacred Deer, Sacred Duty to Protect.’

[6] P.R. Krishnan and S.K. Jindal, ‘Khejri, the king of Indian Thar desert is under phenophase change,’ Current Sci. 108, no. 11 (2015): 1987–90.

[7] Lord Rama is reputed to have worshiped the Shami tree before he led his forces to vanquish Ravana. In the Virata Parva of Mahabharata, there is a story of how the Pandavas hid their weapons in a Shami tree prior to their agyatavasa in King Virata’s kingdom.

[8]A. Rechert, ‘Transformative encounters: destabilizing human/animal and nature/culture binaries through cross-cultural engagement,’ in Construction of Self and Other in Yoga, Travel, and Tourism, eds L.G. Beaman and S. Sikka (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 29–38. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32512-5_4 .

[9] Bikku, ‘Religion and ecological sustainability among the Bishnois of Western Rajasthan.’

[10] Jain, Dharma and Ecology of Hindu Communities.

[11] S. Kedzior S. ‘A Political Ecology of the Chipko Movement’ (Master’s Thesis, University of Kentucky, 2006) 286. Accessed September 26, 2018, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_thesis/289.