Textiles are cultural artefacts that reflect social histories of the places where they originate. In the Indian subcontinent, owing to its vastness, an account of its wide-ranging textiles presents a particularly speckled map. Textiles in India vary from place to place dramatically, not only in terms of the type of material or cloth but also in design, manifesting in them the diversity in geographical and ethnic cultural patterns. And amongst the different types of fabrics available in India—chiefly wool, jute, hemp, silk and cotton—it is cotton that offers the richest styles of expression. While other fabrics have a distinct quality in texture, cotton being relatively flat has been explored most ingeniously by Indian weavers in terms of colours and designs to create striking results (Varadarajan 1984). Craftsmen have devised different design and weaving methods, chief amongst them being bandhani, kalamkari, block print and ikat. The bandhani is a process of knotting, tying and dyeing, traditionally associated with the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan and is known as chungadi in Madura, Tamil Nadu. Painted textiles are called kalamkari and those stamped are called chit or block-printed fabrics. Ikat is the most intricate and elaborate of all these methods involving resist dye as well as weaving of loose threads post the dyeing. The yarn already bears the impression of the pattern when the loom is set for weaving. If both warp and weft are resist dyed the resultant weave is called ‘double ikat’ which is primarily associated with the patola ikats of Patan, in Gujrat (Figure 1). And if either the weft or the warp yarn alone is dyed, the weave is termed ‘single ikat’, more widely produced in Odisha. Despite the supposed influences of Gujarat’s patola on Odishan weaving, the two are strikingly different in design. The Gujarati patolas are recognisable through their bold outlines, geometrical grid-like overall design. However, the Odishan ikat follows a curvilinear style and has a feathery look with hazy outlines (Figure 3). This essay provides a general overview of the latter tradition, as primarily practised in the Sambalpur region in Odisha, with a focus on the profound symbolism and cultural moorings which inform the ostensibly decorative styles. To quote Judith Livingstone’s succinct description of ikat’s multiple cultural connotations, these fabrics ‘have been worn as costume, exchanged as gifts, acquired as items of status and prestige, utilized for ceremonial and ritual purposes. They have also served as a medium of communication between members of social groups, as much as between the physical and spiritual world’ (Livingstone 1994:153).

Ikat is an Indonesian word derived from the word ‘mengikat’, meaning to tie. Apart from India, Indonesia, Japan and China are the other countries in which this method of weaving is widely practised. While indigenously this resist dye and tie method is called bandha kala or tie art in Odisha, because of the international resonance of the term ‘ikat’, this essay will primarily use the latter term to also refer to the Sambalpuri textiles.

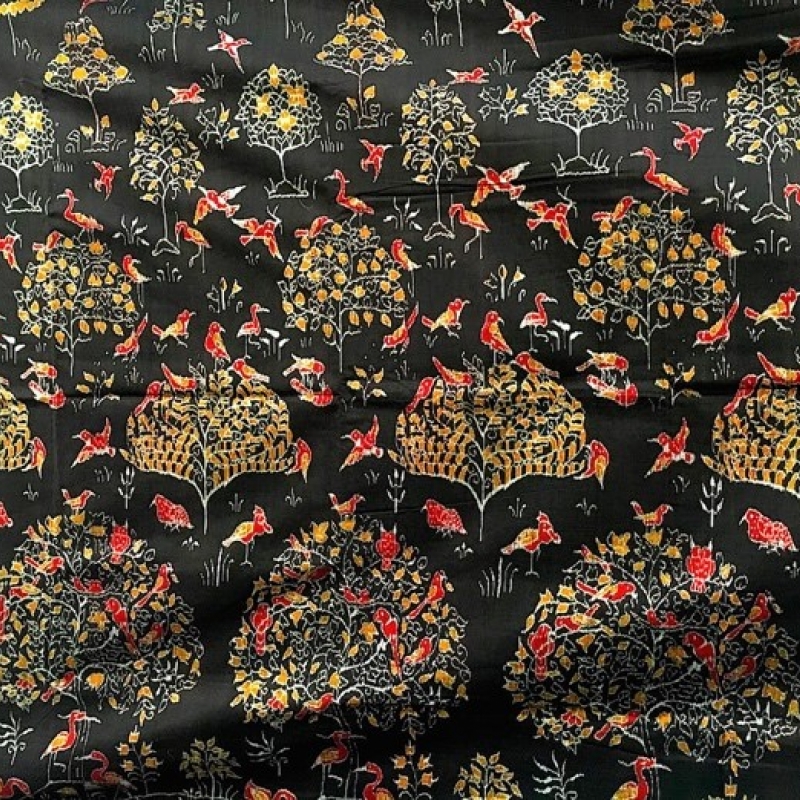

Figure 1: This 19th-century wedding saree is a typical example of the Patola silk from Gujarat. This ikat uses both weft and warp dyeing method. Metallic gold thread is also used in this saree along with silk. Source: Wikimedia Commonshttp://collections.lacma.org/sites/default/files/remote_images/piction/ma-2382345-O3.jpg

Figure 2: Ceremonial Ikat Hanging from Bali, Indonesia, late 19th century. Source: Honolulu Academy of Arts pasted on Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7331824

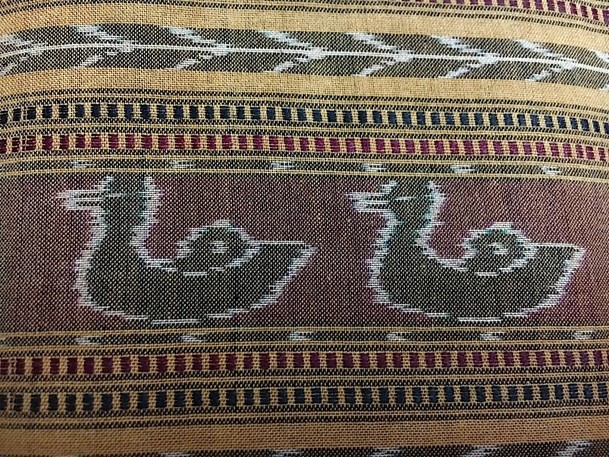

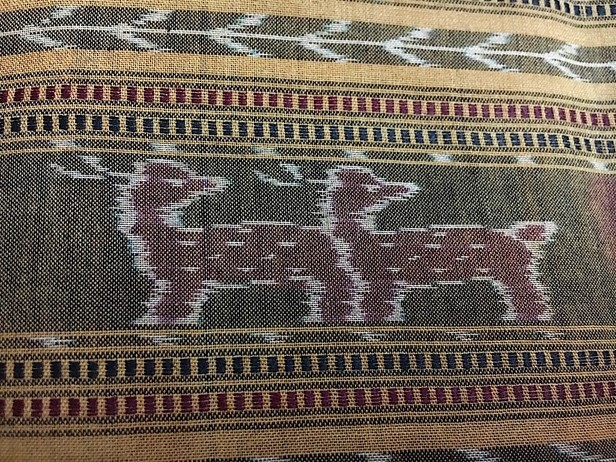

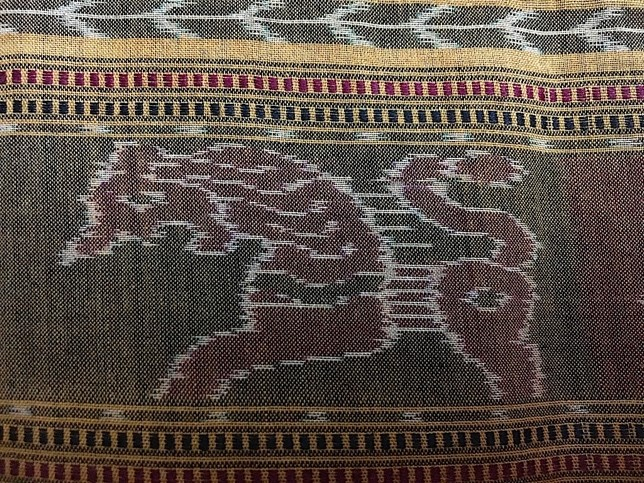

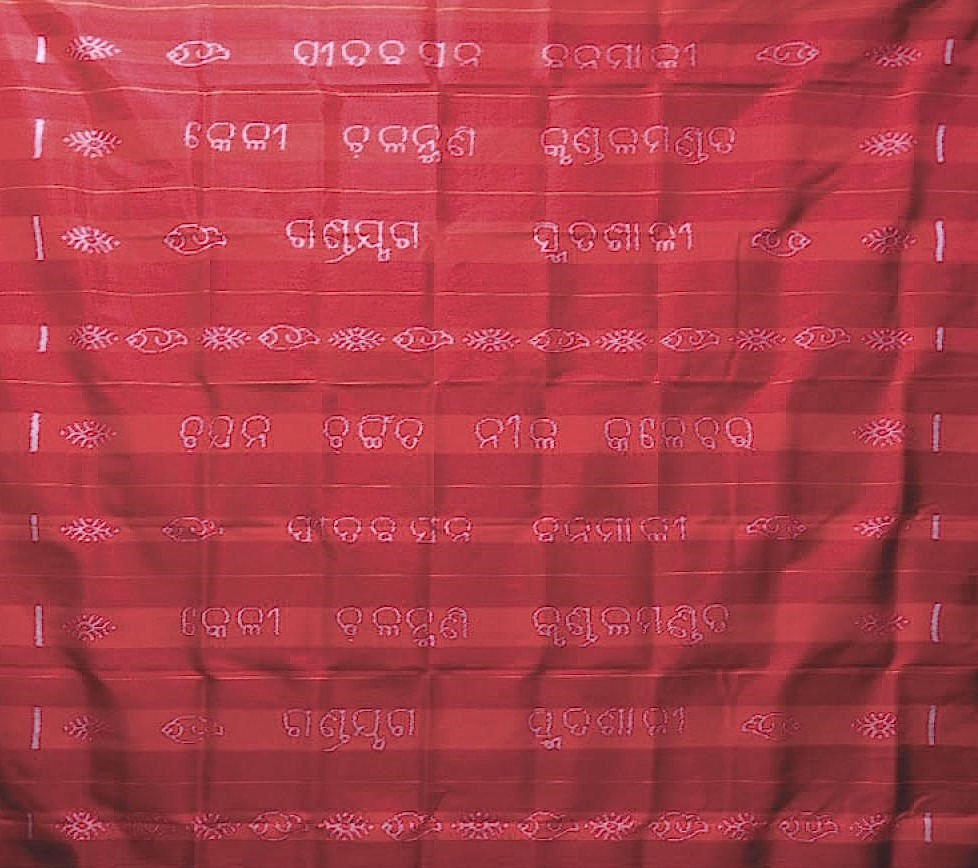

Figure 3: Sambalpuri Ikat. Notice that compared to the geometrical and more precise patola, the Odishan ikat has a curvilinear and feathery appearance.

Design and Symbolism

Ordinary craftsmanship of extraordinary creation—that is bandha kala. One can say this for two reasons. Firstly, ordinary craftsmen of Odisha living ordinary lives and in some cases in abject penury, display extraordinary creativity in producing some of the most exquisite designs in textiles. The famous saying of Odisha’s legendary poet Bhimabhoyi (late 19th century) has remained an inspiration for the weavers, ‘The suffering of humankind—I hope my life becomes hell but alleviates the human condition’. And secondly, through these textiles ordinary life is constantly imbued with an extraordinary vision regarding evolution, the nature of human civilisation, as well as the cultural values of the Odishan society. As the primary wearer, the woman drapes over herself these rich symbolic imageries connecting her everyday world with the divine and the spiritual.

In different scriptural texts or shastras, the Indian woman is associated with qualities of elegance and abundance by the ‘wise men’. For instance, the following old poem cited in Kunja Meher’s (Meher 2004) book affixes various attributes to the Oriya woman in so many words:

Padmini Padmabasini (who smells like lotus) Mrugarajkati (with a waist as slim as a deer’s) Nindeghanajagani (with round thighs) gajabaschali Gajagamini (whose walk is soft and sensual like an elephant’s) kanhi achu dhana (Where are you my dear?)

Dekha Chandranayana (please show your moonface). Bachanu binate gheni (I humbly request you to listen to me).

Kokilakantha jina (whose voice is like a koel bird’s and even better) Chandramukhi lalana (oh moonfaced girl) Mrugachahani (with the swift innocent look of a deer) Mrughakhi (whose eyes are also shaped like the deer’s) Bimbaadhari (with the parrot’s red lips) Meena nayani (fish-like round eyes) Maninimadalasa Mandahasi (the sensitive woman and the one who smiles proportionately—slight, sweet smile) Ghanakesi (with thick hair) Puspabati latika (with hair like the creeper with lots of flowers) Jabaadhari (with the red lips of a hibiscus flower) Dalimbabijadonti (with small white teeth like the seeds of pomengranate) Mrudukumudakanti (your skin color is like that of a blooming lily) Maralagamini (you have a swan-like walk) Chandranane (round is your visage—moonfaced) Nasikatilapuspa (your nose is slender like the flower of the ‘til’ plant) Kusumathani kularajani ghanakesi (You are like a flower with lush hair).

Thus, as seen in these effusive lines describing a woman’s beauty, comparing ideal feminine qualities to nature’s elements had other social connotations. For instance, the ideal woman had to cultivate certain personality traits as the householder—she was the soft-spoken, gentle and forgiving woman. Her physical traits were a reflection of an inner resilience and virtuousness. With innocent, constantly batting doe-eyes (mriganayani, mrugakhi), a body that smelled sweet and pleasant like the lotus flower (padmabasini), soft sensual walk of an elephant which produced no sound (gajagamini), sway of a duck or swan (maralagamani) and the sweet gentle smile on her red parrot-like lips, such a woman, whose outer beauty and sensuality could only correspond to a personality that was loving and undemanding, could shoulder the duties as wife, mother and householder. Such was the fantasised role of women in the shastras, epics, poems and depiction in the architecture of Odishan culture since ancient times. Other major literary inspirations for female representation in Sambalpuri ikat are poet Kalidasa’s Abhijnana Shakuntalam and the verses from ‘Madhumaya’ poems in the book Pranayabalari by renowned Odia poet Gangadhar Meher, who himself belonged to the weaver community. Radhanath Rai’s poems describing the Chilika Lake in Odisha, its water, sky, and birds are also depicted in the sarees.

The traditional Bichitrapuri saree with one of the oldest known designs has therefore recurring motifs of the deer, lion, elephant, geese, ducks in its end panel (Figures 4, 5). While on the surface, deracinated from its context, these motifs might look merely decorative, to depict a horse or camel in these sarees would thus become completely illogical and counterproductive. The Indumati saree depicts all the duties of the Odia housewife and Panchkanya saree shows womenfolk in a specific attractive pose with one leg up, their heads falling back as they play the conch with their mouths. Some of the other key recurrent traditional motifs include the lotus as a symbol of the universe emerging from the sun as well as Goddess Lakshmi’s seat, the conch representing the mystic symbol ‘om’, the tortoise as incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the fish as a sign of evolution as well as one of the eight symbols of good luck, the coiled serpent symbolising the unending cycle of time, peacock for prosperity, and the dharma chakra. The Charuchitrapata saree depicts imageries from the other traditional Odishan art—the scroll paintings or patachitra based on Hindu mythology, especially the life of Lord Krishna. Similarly, designs emphasising a particular dominant motif are codified such as the Mandara Phuliya Kapata (hibiscus flower cloth), Ekphuliya (one-flower design), Dusphuliya (ten-flower design), Boulomaliya (flower garland), Nagabandi (two snakes entangled and facing each other) Aasman Tara (stars in the sky), Sakatapara (depicting carts), etc. In olden times, sarees were also named according to the codified designs each incorporated—Pushbati, Ratnabati, Mriganayani, Gajagamini, Padmavati, Champakmali, Malinitoya, Indumati, Bhanumati, Bharatikusuma, Kalaratna, Ratnabati, Panchkanya, Kalingasundari, Utkalaratna, Topoi, etc. The famous Pasapalli saree with its distinct chequered design is inspired by a traditional board game, pasa. In most of these sarees, it is the anchal or pallu, i.e. the end panel that is the most important part of the design and visually striking. Adorned in these assemblages of auspicious motifs on the sarees, the virtuous woman is believed to constantly carry upon her body and be reminded of the traditional values of Odishan culture.

However, apart from the secular and day-to-day usage as women’s drapes, the ikat textiles also served an important religious function. In this regard it is worthwhile here to discuss the Gitagovinda cloth as an example of the contexts within which Odisha’s ikat was originally produced and received. The Gitagovinda is probably one of the oldest surviving types of the religious ikats of Odisha. These are especially made by the community of Nuapatna weavers in Cuttack district, with almost 90 per cent of this village comprising of different castes of hereditary weavers. On a mere descriptive level, the Gitagovinda is typically made in silk containing verses from the religious text, Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, a devotional poem dedicated to the Hindu deity Krishna, produced through the weft ikat technique (Figure 6). The end panel or pallu is typically made out of three dominant colours, corresponding to the chariots in Ratha Yatra festival—green for the deity Balabhadra, red for Subhadra and yellow for Jagannath. The verses most frequently deployed in these fabrics are the first part of the Gita Govinda text on the Dasvatara or Vishnu’s ten incarnations. However, on a cultural level, the Gitagovinda cloth is circulated in the extremely ritualistic domains within the Jagannath Temple of Puri, defining and negotiating anew hierarchies within the religious structures between the devotees, the different kinds of sevakas or priests of the temple, etc. Moreover, as studied by Hacker, in medieval times, political power was deeply intertwined with the religious domain, and in the case of the Odishan empire, the king would actively partake in the temple rituals and strategically place himself in a high status within the temple hierarchies, often identifying himself as a symbolic incarnation of the deity itself (Hacker,1997). This would in turn shape relations with feudatory states and neighboring kingdoms and the trade dealings. For instance, the sacred Gitagovinda cloth, apart from being offered as gifts, would also be bartered for iron, wood and ropes to make the deities’ carts for Ratha Yatra. While the kings and heads were offered silk clothes, the rest of the ministry and family were given cotton fabrics, establishing hierarchies and marking status and prestige via means of the sacred textile which became an important visual and symbolic vehicle for formalising such political transactions. Thus the cloth served ceremonial, religious as well as political functions all at once.

1.

3.

5.

Figure 4: These motifs occur recurrently in the traditional Bichitrapuri saree containing animal motifs in its end panel. The duck’s rhythmic movement (1), the deer’s beautifully batting innocent eyes (2), the elephant’s gentle walk and sensual sway of hips (3), the lion’s narrow waist (4) are compared to the female body and features. The lotus flower depicts the seat of goddess Lakshmi (5), and the conch shell stands for prosperity (6).

Figure 5: The fish, rudraksha (sacred seed) and flower motif can be seen in this traditional border.

Figure 6: The Gitagovinda sacred cloth with verses from the Gita Govinda text.

Figure 7: The traditional animal motifs of elephant, duck, lion, deer along with conch shell, temples and the lotus flower can be seen in the end panel of this saree, whose details are produced above in the previous images. This is the traditional Bichitrapuri style, one of the oldest known Sambalpuri designs.

Origin and Decline

A semblance of the Odishan ikat can be seen in the garments of the beautiful sculptures in Konark Temple. In the Chandi Mandir in Saintala also one can see the attractively patterned drapes resembling the ikat fabric on figurines of Ganga and Jamuna. So also is the case with the sculptures of Baidyanath Temple in Sonepur district. R.N. Mehta argues that the ikat tradition dates back to about the 13th century CE in ancient Kalinga (cited in Livingstone 1994). According to local oral history, the group of Bhuliya weavers were originally from Madhya Pradesh during the 18th century, and later migrated to the Sambalpuri area of Odisha and brought knowledge of the Gujarat patola ikat tradition to this region as well (Livingstone 1984). In more recent discussions of this art, T.N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufacturers of India (Mukherjee 1888) has written and highly praised the art of matha saree (coarse silk saree) in Barpalli. O’Molly, a British traveller, has also spoken of the Bhuliya tribe (O’Molley 1908). O’Molley in 1809 CE writes of his travels to Borpalli Patora, Kshetra Bhushan, Sapta Padi, Bichitra Puri, Mukta Jhari, Kumbha, etc., and speaks of the different weaving traditions in these areas. At different times, various experts have thus claimed the bandha kala art to be one of the oldest textile crafts of India. Notwithstanding these sources, the exact origin of this art in the eastern region remains unknown. While the origins seem unclear, the decline of this craft from a state of widespread production and export to neighboring areas to gradual poverty of weavers, has been traced to the 18th century. Nabin Kumar Jit cites the study of T. Motte in locating the decline of textile production in Odisha since the time of the Maratha empire of the 18th century (Kumar 1980). According to this account, the Maratha administration discouraged the local textile occupation because cotton, which was not produced in Odisha, was imported and traded with Maharashtra through the land route Raipur–Sambalpur for cheap rice and salt. But since the Maratha government instead preferred diverting Odisha’s rice to the city of Nagpur, huge customs duties were levied on the import of cotton bales to manipulate trade relations.

While the decline had started with the Marathas, a widespread regression ailed the Indian textile art subsequent to colonial exploitation, which transformed India from an exporter of manufactured goods to an importer of cloth. The British used political power to dominate a rival with whom they could not have competed on normal terms (Kumar 1980; Mukund 1992). During the last quarter of the 18th century, cotton textiles from Odisha were initially exported by the British. However, this alliance was only momentary and eventually the custom duties levied on cotton bales became so high that indigenous production and trade further declined. The British encouraged import of machine made clothes from Calcutta into Odisha. Gradually the indigenous weaving industry began to cater only to the poor peasantry of Odisha who could not afford the imported clothes. Nabin Kumar further states how the passing of the 1833 Charter Act sounded the death knell for local village level industries (Kumar 1980). Earlier, weavers in Balasore district of Odisha would belong to the middle class, but gradually this community was reduced to abject poverty. Not surprisingly, during the 1865–66 famine, weavers were one of the worst hit, resulting in their large-scale migration towards south-west Bengal to seek work as manual labourers. This crisis was only aggravated when the discovery of chemical dyes further towards the last quarter of the 19th century escalated the disparity between handicrafts and factory-produced goods (Mukund 1992).

Weavers

The villages where ikat weaving is practised in Odisha are Mankedia in Balasore or Mayurbhanj district. In the Balangir district in West Odisha, ikat weaving is done in Barapalli, Remunda, Jhiliminda, Mahalakata, Singhapali, Sinepur, Patabhadi, Sagarpali, Tarabha, Biramaharajpur, Subalaya, Kendupali, Jaganathpali, and Kamalapur. In Cuttack district it is produced in the villages of Badamba, Nuapatna, Maniabadha, Narashinpur, Tigiria and many more. Thus while several villages of Odisha are involved in this craft, it is the Bargarh district that is most widely recognized for the Sambalpuri sarees which have the maximum reach beyond Odisha. The term ‘Sambalpuri’ for these textiles is therefore misleading, for they are not actually produced in Sambalpur, but its neighboring areas. However, Sambalpuri term is used more of a metonymic manner, referring to the larger distinct performance and art culture of this region.

The western part of Barpali in Bargarh district and its nearby areas are famous for producing silk, tussar (coarse silk) and cotton. Tastefully designed cotton sarees are made by the Bhuliya community of Meher tribe. By putting in much hard work and with knowledge passed down many generations, this community specialises in making fine cotton sarees. The master weavers are skilled in creating precise and intricate patterns. The Bhuliyas belong to a higher social stratum than ordinary weavers. Apart from Bhuliyas, the Mehers of Sonepur and Bargarh and the Patras from Nuapatna and Cuttack region are other major weaving communities.

Another important weaver community of Barpalli is the Kostha. The Kosthas also use the Meher surname but do not make cotton sarees or ‘bandha’, i.e. they do not perform much of the tie and dye work. Instead they specialise in silk thread work and typically make the Kumbha saree, dhoti, pachoda (towel used for prayers) and in addition they also possess expertise in butti work, i.e. tiny circular embroidered motifs spread over the saree’s body. In Sarola Das’s Odia translation of the Mahabharata, one finds the description of devanga vastra, referring to cloth made by Kosthas in silk and tussar. It is believed that during Puranic times, the Kostha community was famously given the title ‘Devanga’ by the gods, for the sheer beauty of the fabrics and the creator’s expert handiwork.

Contemporary scene

Although the British wanted to terminate the handweaving industry of colonial India, the ikat craft still survives. Radhashyam Meher, Kunja Bihari Meher, Chaturbhuja Meher and Krutartha Acharya are some of the leading exponents of Sambalpuri ikat who have helped display this art on the world stage. After Independence, the well-known freedom fighter of Sambalpur, Sri Radhashyam Meher, made an active effort to keep the craft alive. Padma Shri Dr Krutartha Acharya also started a cooperative which was revolutionary in giving the weavers more remuneration. During the 1970s, with his extraordinary proficiency, Padma Shri Kunjabehari Meher created a special interest for this art beyond Odisha and even generated international demand through live demonstrations of Sambalpuri ikat weaving process in Philadelphia (USA), Hong Kong and London. In 1982, Chaturbhuja Meher resigned from a government job and started his own weaving factory in his native place Sonepur. Here he explored and created numerous new patterns and designs in pure silk and tussar fabrics and also promoted other traditional handloom arts of India. His products also reached a wide market and for the first time fetched better prices for the textiles throughout India and abroad.

During the 1920s Odisha ikat had begun to acquire a level of sophistication in its design and style, but even then production mostly catered to local consumption and use in temples and marriages. The village women till date wear self-woven sarees. The older women drape them without a blouse. And even school uniforms are made out of these local fabrics in areas like Barpali. It is only during the 1970s that this handloom industry acquired wider recognition and started to direct products to an all-India and international market. To appeal to this wider market, apart from sarees, other products such as scarf, bed sheet, bedcovers, handkerchiefs, dupatta, dress material, screens, curtains and wall hangings are now being made and becoming increasingly popular. As already discussed, while in the olden days, the design motifs were inspired by the stone carvings in temples and Odia and Sanskrit literature, in the more contemporary sarees, a wide range of designs are drawn from folk arts, mythology, architecture and religion, and some experimentation is being done with the layout and distribution of motifs to cater to more modern and international tastes.

Soon after Independence, the government had also opened several state organisations to support and market Odisha’s textiles and crafts, chief amongst them being Boyanika, Utkalika and the Sambalpuri Bastralaya. However, despite some measures taken to aid manufacture and reach, the Sambalpuri ikat remains limited in its economic prospects, with weavers barely surviving on their meagre incomes. Bargarh, for instance, has more than 12,000 looms, with several recipients of national and state awards, as well as two Padma Shri honours. This is possibly the only weaving community in the country with so many awards to its credit. Yet, despite the honours and the ubiquities, Sambalpuri ikat has been unable to carve out a place for itself outside the state. One of the prime hurdles faced by weavers is the procurement of raw material due to the constant fluctuations in the prices, which in any case tend to be high causing the smaller weavers to loan raw materials or threads on interest. Unfortunately, even the export market for Sambalpuri ikat is negligible, and, within India, weavers feel that due to lack of proper market surveys of demand and tastes, products are not able to reach the buyers effectively.

The mid-1990s can be seen as a point of commercial peak for Sambalpuris. During this time the textiles started being shown at the Surajkund or Dastkari Haat fairs in and around New Delhi. Demand has seen a steep decline since, particularly in the last decade. Locally, more and more consumers are moving towards the factory-produced printed products which are extremely cheap compared to the expensive handwoven clothes. Even the most basic Sambalpuri cotton saree made of coarse thread costs anything between 500 rupees to 2,000 rupees. The more intricately patterned and finer cotton sarees range between 5,000 to 15,000 rupees. These are possibly the highest priced cotton products in the market at par with silk products. The silk ikat sarees start from 8,000 rupees onwards. The steep costs of these textiles is primarily due to the labour-intensive and time-consuming nature of its production. Typically, the entire weaver’s family has to contribute to the making of each saree which takes between two or three days on a minimum to as long as six months for the highly sophisticated works. Exceptionally patterned sarees made for exhibitions abroad take months and even a year or more to complete. They are woven by rural weavers but the designs remain the copyright of master weavers. Master weavers are not only regarded as experts in the field but also culturally and financially more resourceful. They not only create the intricate designs but also support other weavers by providing raw material and purchasing back the finished products to market them adequately. Sometimes the master weavers also acquaint the local weavers with market trends and provide technical guidance and innovative designs to boost the quality of products.

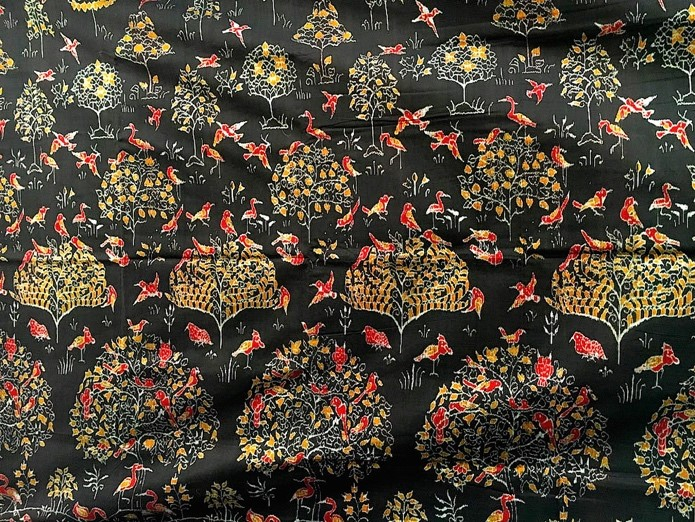

Figure 8: This exquisite cotton sari called ‘Tree of Life’ displays an elaborate design, particularly challenging to execute in the ikat method. It takes about a month or two to produce a single sari like this by an expert tier and weaver.

Conclusion

These days, with the advent of automatic looms the traditional designs are being transferred onto polyester, nylon, etc. But cotton and silk were the original raw materials for ikat and the effect with synthetics is far from the striking precision that is attained through manual supervision. Clearly in the case of ikat, machines have failed compared to hand art. It is the weaver’s discretion and the soft and magical touch of his hand which produces such symmetry in the designs of the borders and end panel that this becomes impossible to be reproduced by mechanical means. Tie and dye art is unique especially because of this manually produced synchronisation and balance. There is no limit to this art’s design potential. With little thread, one can make any number of intricate designs, including realistic portraits. The term ‘Devanga’ used to refer to weavers is therefore intuitive here, an ancient divine attribution in oral history but also an acknowledgement of the extraordinary artistic spirit of the common weaver whose entire family and life revolves around this art. As famously stated by Berkely, ‘the hand art cannot be replaced by machine because the spirit is part of the craft.’

Bibliography

Hacker, F. Katherine. 1997. ‘Dressing Lord Jagannatha in Silk: Cloth, Clothes and Status.’ Anthropology and Aesthetics 32:106–124.

Kumar, Nabin. 1980. ‘Decline of Cotton textile Industry in Odisha.’ Journal of Odisha History 1.2.

Livingstone, H. Judith. 1994. ‘Ikat Weaves of Indonesia and India:A Comparative Study.’ India International Centre Quarterly 21.1:152–74.

Meher, Kunja. 2004. Bandha Shilpi Ra Bidesa Anubhuti. Barpali: Kalabharati Museum Trust, Mita Printers.

Mohanty, Bihoy Chandra, and Kalyan Krishna. 1974. Ikat Fabrics of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. Calico Museum of Textiles.

Molley, L.S.S. 1908. Bengal District Gazetters. Puri: Calcutta.

Mukherjee, T.N. 1988. Art Manufacturers of India.

Mukund, Kanakalatha. 1992. ‘Indian Textile Industry in 17th and 18th Centuries: Structure, Organisation and Responses.’ Economic and Political Weekly 27.38:2057–2065.

Varadarajan, Lotika. 1984. ‘Designs in Cotton: Horizons of the Past and Present by in India.’ International Centre Quarterly 11.4:69–78.