The ‘Alchi murals’ have become one of the highlights of the cultural heritage of Ladakh leading to the transformation of the site of Alchi—now a major tourist destination as well as a complex of monuments protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Until recent scholarship closely examined this corpus of art and architecture, uncovering a complex history, the early temples of Alchi, as well as the Sumda and Mangyu monasteries, were directly related to the ‘Second Diffusion’ and the patronage of a key figure, Rinchen Zangpo. Also remembered as the lotsawa (‘translator’) for translating copious Buddhist texts from Sanskrit to Tibetan after having received training in the Indian Buddhist centre of Kashmir, he is credited with building numerous chortens (stupas or reliquaries) and temples as monuments to the revival of Buddhism in the Tibetan regions (https://www.sahapedia.org/cross-cultural-influences-the-early-buddhist-art-of-ladakh) . However, recent scholarship has revealed no material evidence linking the ‘Alchi Group of Monuments’ with Zangpo. Indeed, the Alchi Group in its earliest phase appears to date to 11th century, about a century later than Zangpo’s time, as is discussed below. The monuments have come to be identified together on grounds of religious iconography and style rather than direct patronage.

Religious Iconography

Tibetan Buddhism, in short, is a form of Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism, which in turn is derived from Mahayana Buddhism—the other major tradition of Buddhism being Theravada Buddhism. It was forms of Mahayana Buddhism that became prevalent in the Buddhist countries of north Asia, i.e. Tibet, China, Mongolia and Japan. Mahayana Buddhism itself is marked by an extensive pantheon of Buddha figures, Bodhisattvas (‘Buddhas to be’), minor and major male and female deities, including protector ones, as well as, later, semi-divine teacher figures. All of these divine and semi-divine characters are recognisable by their physical attributes such as their colour/complexion, appearance and number of arms, their animal mount/vehicle, as well as their accoutrements such as the objects that they hold and the costumes that they wear. Vajrayana Buddhism is further characterised by esoteric texts and rituals that require the guidance and interpretation of a teacher, leading to the cult of the lama or monk.

The Alchi Group belongs to the formative phase of Tibetan Buddhism (mainly 10th–11th century, but extending up to the 13th) marked by a reference to Indian texts and teachers. In the case of Ladakh-Zanskar and Kinnaur-Spiti (in modern India), and Guge-Purang (in the Tibetan Autonomous Region or TAR in China), collectively known as the western Tibetan regions, the Buddhist centres of Kashmir became the main point of reference. In this early period, a particular class of Tantric Buddhist texts, known as the Yoga Tantra, seems to have been popular in the western Tibetan regions, and the pantheon and themes from it are represented in the clay sculptures and mural paintings of the Alchi Group (for more on this, see Snellgrove and Skorupski 1977:8–15). The Yoga Tantra is dominated by a transcendental Buddha known as Vairochana, who is associated with the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. Four other Buddhas associated with the four cardinal directions—the red Amitabha of the west, the blue Akshobhaya of the east, the green Amoghasiddhi of the north and the yellow Ratnasambhava of the south—revolve around the sparkling white figure of Vairochana. These five Buddhas are known as the Tathagata Buddhas. Each of these Buddhas heads a family that includes counterpart goddesses and Bodhisattvas. This system is elaborately represented as a mandala consisting of concentric circles locating Vairochana at the centre, i.e. the heart of the cosmology and ritual (Fig. 2). The different concentric circles of a mandala represent the progression to the central core that represents enlightenment, the ultimate Buddhist goal. Tibetan religious art, of which the art of the Alchi Group is a manifestation, serves to illustrate complex Buddhist philosophies and as a tool in contemplation and meditation.

Fig. 2: Mandala, Alchi Sumtsek, first floor, back wall (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

Alchi Sumtsek

The Alchi monastery basically consists of a complex of temples that has accrued between circa 11th and 15th century. The ‘sacred space’ of the choskhor is demarcated by the remains of a low wall. The greater site of Alchi includes the ruins of a tiny fortress, which is an indication, as are the historical scenes (https://www.sahapedia.org/cross-cultural-influences-the-early-buddhist-art-of-ladakh), of its one-time importance as a local power base. I have elsewhere also discussed the possibility of the monastery, or at least the site, having also served as a caravanserai given its location on the south bank of the river Indus within reaching distance of the historical Leh-Kashmir highway, currently NH 1D, on the other side of the Indus (Chandra 2008:97–98).

Of the five temples that constitute the choskhor, the oldest are the Dukhang (Assembly Hall) and the Sumtsek (‘three-storey temple’), and it is indeed these two temples that are included within the classification of the Alchi Group of Monuments.[1] Some details about the foundation of these temples are recorded in inscriptions at the temples (Denwood 1980:119–54). The Dukhang was founded by a patron, Kalden Sherab, from influential Ladakhi clan of the time, the Dro clan. Sherab also built the aforementioned fortress and a bridge across the Indus connecting Alchi to the highway. A member of the same clan from a few generations later, perhaps called Tshulthim Ö (Denwood 2014:n. 9), seems to have built the Sumtsek. The scholar who translated most of the inscriptions in the two temples—also the first to do so—Philip Denwood, dated the Dukhang and the Sumtsek to earlier and later in the 11th century respectively (Denwood 2014:182). This was challenged by Roger Goepper in the next major study of the Sumtsek—also the most comprehensive documentation of the temple to date—when he dated the Sumtsek to late 12th to early 13th century based on a series of portraits and corresponding inscriptions discovered by him in the second floor of the temple (Goepper 1996:212, 216–17). Most recently, Denwood has made a strong case on grounds of paleography, orthography, style and historical circumstances upholding his original dating (Denwood 2014), as is discussed below.

Although the Dukhang contains some of the most important historical scenes (https://www.sahapedia.org/cross-cultural-influences-the-early-buddhist-art-of-ladakh), the Sumtsek is, arguably, painted with the most interesting mural paintings. Indeed, such is the skill with which they were painted that, to date, they gleam brightly within the dim interiors of the temple. The entrance wall above the door is often painted in Tibetan Buddhist temples with fierce protector deities that symbolically purify and protect these spaces. In the Sumtsek, this role is performed by Mahakala—blue-black in colour, having three eyes and two fangs, holding a chopper and a skullcap, wearing a tiger-skin loin cloth, decorated with skulls and snakes, and treading a corpse (Fig. 15). Mahakala is only one of many Buddhist deities adapted from the Hindu pantheon, the god Shiva in this case.

Fig. 15: Mahakala, Alchi Sumtsek, ground floor (photto by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

The tall temple is dominated by three huge clay statues of Bodhisattvas Avalokiteshvara (Fig. 16), the Bodhisattva of compassion, Maitreya, the future Buddha, and Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of wisdom. Measuring at least four metres, they rise from the ground floor, their crowned heads jutting into the first floor. Note that narrow galleries enable the viewing of the paintings on the first and second floors in place of full-fledged ceilings dividing the different floors. The Bodhisattva figures are located in deep alcoves in the left, back and right walls. An inscription—one of many contextualising the temple—identifies them as the receptacles of the body, mind and speech and with the sambhogkaya (glorious body of the Buddha), dharmakaya (absolute body) and nirmankaya (physical body) forms of the Buddha. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara is recognisable as such as he holds a lotus and performs the abhaya mudra (the gesture of reassurance) with his two upper hands.

Fig. 16. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Alchi Sumtsek, ground floor (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

What is unusual about this representation as well as the other Bodhisattva statues is the presence of four hands. All the Bodhisattvas wear intricately patterned dhotis, with even the dhoti designs serving a thematic purpose. The Avalokiteshvara’s dhoti is painted with palaces, Buddhist and Shaiva shrines, and even hunting scenes (Fig. 13). Roger Goepper has identified these sites with the then geography of Kashmir (Goepper 1996:50–71). In the crown of the Avalokiteshvara sits the Tathagata he is associated with, Amitabha; multiple miniature representations of whom also cover the portions of the left wall to the sides of the alcove. The sides of the alcoves towards the bottom are also painted, mostly with historical scenes and inscriptions (https://www.sahapedia.org/cross-cultural-influences-the-early-buddhist-art-of-ladakh) (Such as Fig. 10).

Fig. 13: Detail of Avalokiteshvara's dhoti, Alchi Sumtsek, ground floor (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

Fig. 10: Historical scene, Alchi Sumtsek, ground floor (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

One of the most beautiful painting compositions from the Alchi Group appears on the left wall inside the Avalokiteshvara alcove. It represents an elaborately coiffured and bejeweled six-armed Shyamatara or Green Tara (the ‘saviouress’ goddess) (Fig. 14). Previously identified either as a composite of the goddesses Tara and Prajnaparamita (the goddess representing transcendental wisdom) or the Durgottarini form of the goddess (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1977:56; Pal and Fournier 1982, 36; Huntington 1985:382–83; Goepper 1996:72–73), I have identified her with the Dhanada (wealth-endowing Tara) and Durgottarini (Tara who protects in distress) forms of Tara on the basis of the attributes in her six hands, and as a goddess who was specific to the circumstances of Alchi as a resting place for traders and merchants (Chandra 2007:72–77; 2015, 83–98).[2] It is reflective of the local variations within Buddhist ‘templates’ as the religion was adapted to diverse regions.

Fig. 14: Shyamatara, Alchi Sumtsek, ground floor (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

The next alcove is the one in the back with the red-coloured figure of Maitreya. Considering his destiny as the successor of the last historical Buddha Shakyamuni, it is not surprising that his dhoti is painted with scenes from the Life of the Buddha. The Tathagata that sits in his crown is Vairochana, who is associated with the historical Buddha, as is previously mentioned. But the Tathagata that recurs in miniature form on the sides of the back wall is Akshobhaya. One explanation for the dual association may again be found with the theme of the historical Buddha. Akshobhaya performs the bhumisparsha mudra or the earth-touching gesture that Siddhartha Gautama had performed to call upon the earth to witness his enlightenment transforming him from a seeker or Bodhisattva into the Buddha. The niche in the right wall contains the yellow Manjushri, whose dhoti is painted with the 84 Mahasiddhas, yogis or ascetics who obtained special, magical powers through unconventional means.

The first floor is mainly painted with mandalas—four on the entrance wall and two each on the other walls (See, for example, fig. 2). Both the male and female aspects of the Vairochana cycle are depicted in the mandalas in the early Alchi temples (For details of these mandalas, see Goepper 1996:149 –223).

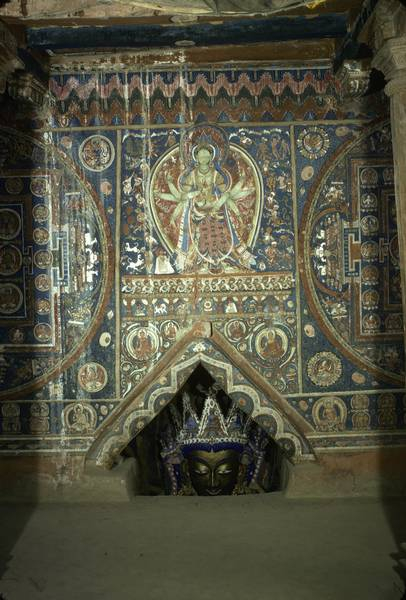

In between the mandalas on the four walls appear paintings of different deities. The fierce protective deity Yamantaka in a cremation ground is painted on the entrance wall above the door. An unusual 11-headed, 11-armed form of Avalokiteshvara dominates the left wall. The back wall is painted with the Buddha Shakyamuni identifiable on the basis of his mudra, dharmachakrapravarttana, or the gesture of turning the Buddhist wheel of law, i.e. preaching. Green Tara as Ashtabhayatrana, the ‘saviouress who protects from the eight kinds of dangers’, i.e., wild animals (specifically identified with the lion and the elephant), snakes, fire, water, theft, imprisonment and demons, is depicted as a stately figure on the right wall (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Ashtabhayatrana Tara, Alchi Sumtsek, first floor (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

The second floor barely qualifies as a floor since a small window accessed from outside is the only entrance into the cramped space. The left, back and right walls are covered by a mandala each. On the entrance wall, a triad of protective deities—Achala in the centre, flanked by two forms of Kubera, Ucchushma and Jambhala—appear on a horizontal panel above the window, on the vertical panels along the window is painted a lineage of ascetics and monks (Fig. 18). The last of the lineage is Drigungpa or Jigten Gonpo, founder of the Drigung sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Since Gonpo lived between 1143 and 1217, the Sumtsek was attributed by Goepper to late 12th to early 13th century, as discussed above (Goepper 1996:216–17). However, scholars such as Denwood have pointed to the traces of rewriting of inscriptions that suggest a later takeover by the Drigung order in the fiercely competitive world of Tibetan Buddhist sects leading to the later insertion of the Drigung portraits (Denwood 2014).

Fig. 18. Entrance wall, Alchi Sumtsek, second floor, (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

Also worth noting is the sumptuous ceiling of the Sumtsek, painted with panels made to resemble strips of textiles.These ceiling panels include, among others, Central Asian motifs such as archers mounted on horses turning around to impart the ‘Parthian shot’, fantastical griffin-like creatures and silhouettes of dancing women wearing ‘harem pants’ (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. Ceiling panels, Alchi Sumtsek (photo by Jaroslav Poncar, courtsey WHAV)

Sumda

The village of Sumda Chung in Zanskar preserves the remains of an ancient monastery, which includes a Dukhang flanked on its two sides by temples housing huge clay statues of Maitreya (right) and Avalokiteshvara (left). The Dukhang is dominated by an elaborate three-dimensional mandala made of clay against the back wall. This sculptural composition features the four-headed Vairochana surrounded by the other four Tathagatas—left, Ratnasambhava and Akshobhya, and, right, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi. It is placed against a backdrop of mural paintings, only fragments of which remain, of multiple miniature Buddha figures.

On the left wall is painted a specific kind of mandala, the Vagishvara Manjushri Dharmadhatu mandala, consisting of the central figure of Manjughosha. Akshobhaya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi occupy the appropriate cardinal positions in the mandala. On the right, opposite, wall is a mural of Vairochana. A memorable detail in the paintings in the Dukhang are particularly beautiful depictions of apsaras (fairies) floating in the air.

Mangyu

Like at Alchi and Sumda, the temple complex lies within the Mangyu village. This is a distinguishing feature of the early Ladakhi monasteries as opposed to the later monasteries that are perched on hilltops, ‘lording over’ associated villages that surround the base of the hill. The way to Mangyu is along the Indus through a valley and up an incline leading to a secluded location, not far from Alchi, but off the Leh-Kashmir highway.

The temple complex consists of two adjoining squarish Dukhangs through narrow rectangular entrance halls. The entrance halls are flanked by two tall chapels, each dominated by a huge clay statue of Maitreya, reminiscent of the Bodhisattva statues in the Alchi Sumtsek. The Dukhang on the right contains an elaborate composition of clay sculptures against the back wall, at the centre of which is a large seated statue of the Buddha Vairochana in his four-headed form. It is, hence, known as the Vairochana Temple. Vairochana is placed within an arch, from which jut vegetal scrolls and smaller arches that contain the entourage of goddesses, subsidiary deities and the other Tathagatas. Although the original mural paintings of this temple have barely survived, various mandala can be discerned: one featuring Shakyamuni, the other Vairochana, in keeping with the larger theme within the temple complex. A third mandala is dedicated to fierce deities, while a fourth is of the eight nagas (serpent godlings), which, according to Lokesh Chandra, are often painted to induce rainfall.[3] The early Ladakhi penchant for patterned textiles is seen here as well since, like in the Alchi Sumtsek, the ceiling is painted with textile patterns, although these paintings are, unfortunately, blackened with soot.

The Dukhang to the left was once dominated by a painting composition of Shakyamuni along with his disciples, obscured today by bookshelves (Luczanits 2004:164). To add insult to injury, the temple has also come to be known, not as the Shakyamuni Temple, but after a later image of the 11-headed Avalokiteshvara that joins the bookshelves in hiding the original painting composition. Traces of painting of the Life of the Buddha carry forward the theme of the historical Buddha. Christian Luczanits dates these temples to later than the Alchi Dukhang but earlier than the Alchi Sumtsek (his dating of which is later than that of Denwood’s) to circa 1175 (Luczanits 2004:164).

The gigantic statue of the Maitreya in the chapel to the right is four-armed. Echoing the theme of the ground floor of the Alchi Sumtsek, Maitreya is accompanied by the Manjushri and Avalokiteshvara, although not on the same scale, as they are simply painted on the side walls and not in very large format at that. Interestingly, if one were to look closely at the dhoti of the Maitreya clay sculpture, one would find that it is painted with frames created by distorting fantastical animal figures with miniature representations of ascetics inside. Yet another feature shared with the Alchi Sumtsek. Indeed, here the dhoti is even more fabulous than the dhoti of the Maitreya in the Alchi Sumtsek on account of the eccentric representation of the animals as framing devices! On stylistic grounds, in comparison with Alchi, Luczanits dates this chapel to circa 1200 (Luczanits 2005:167). The chapel on the left contains a two-armed statue of Maitreya. The murals paintings in this building are also, regrettably, damaged, although they seem to have represented mandalas of the Vairochana cycle. This chapel is dated to a slightly later period, 1225 (Luczanits 2004:170).

Also worth mentioning is a chorten from about the same period as the temple complex since it contains some excellent specimens of early western Tibetan painting. In the top of the chorten, all four sides contain a niche, three of which still preserve clay sculptures of the Bodhisattvas Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri and Vajrapani (the Bodhisattva holding the vajra or thunderbolt representative of Vajrayana Buddhism). Around the niches are painted Tara and Prajnaparamita in a similar, even if less sophisticated, style as the goddesses in the Alchi Sumtsek, the Tathagatas, and the fierce deities Yamantaka and Hayagriva. These artworks may be dated alongside the left Maitreya chapel. It is worth noting that the last major study of Mangyu monastery is included in Luczanits’ seminal book on the early clay sculptures of the Western Himalayas (Luczanits 2005). His dating of the different temples is based on stylistic comparison with the Alchi Dukhang and Sumtsek paintings based on Goepper’s dating. The dating of Mangyu monastery may have to be revisited in light of Denwood’s recent arguments pertaining to the dating of the Alchi Sumtsek, in which case the dates of Mangyu monastery may have to be brought forward by about a century. Unfortunately, so little is known about the early history of Ladakh, 10th–13th centuries, that such dating controversies are inevitable and we can not be very sure of the precise circumstances that gave rise to the monuments of the Alchi Group. What is indisputable is that early Ladakh had enough resources and skills to build such splendid monasteries, informed by cross-cultural influences, as discussed in the overview article by Marjo Alafouzo and the following, final, section of this article.

Painting Style

The style in the paintings from the Alchi Group can be located within the wider ‘Kashmiri’ tradition, so-called since the style seems to have had its roots in the Kashmir valley of the seventh to 12th century, although the mechanisms by which it spread across the western Himalayas, from western Tibet to present-day Himachal Pradesh has not been fully mapped. This style informs a remarkably diverse group of western Himalayan art, including metal, stone and wooden sculpture, and painting (Chandra 2013:373–75). Some of the features that identify this style across such a wide range can be seen at the Alchi Group. They include the trefoil arch and and pyramidal roof under which deities are placed, as well as the thrones on which they sit, often incorporating lions and load-bearing characters (See, for example, Figs. 20 and 21). The Alchi Sumtsek has the same receding ‘lantern ceiling’ as the stone temples of Kashmir and the early wooden temples in such parts of Himachal Pradesh as Chamba (See, for example, Fig. 22). Many of the ceilings in the Alchi Group are painted with textile patterns. The Kashmiri style seems to have incorporated a love of rich textile design. This is seen even in related sculptures, in which the dhotis (lower garments) are carved with intricate patterns (See, for example, Fig. 21). All the figures in the Alchi Group paintings wear colourful clothes painted with incredibly fine details. Like the later-period Buddhas in the Kashmiri style, the Buddha figures among the Alchi Group paintings wear pleated robes (See, for example, Fig. 23).

Fig. 20. Trefoil arch within a pediment, Lakshana Devi temple, Brahmaur, Chamba, ninth century (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Fig. 21. The river goddess Ganga on a doorjamb, Mirkula Devi temple, Udaipur, Lahaul, circa 11th century (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Fig. 22. The lantern ceiling of Lakshana Devi temple (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Fig. 23. The Buddha, Mirkula Devi temple (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Perhaps the most distinguishing trait of the Kashmiri style is the physiognomy of the figures, which is defined by wasp waists and visible abdominal muscles in the case of both the genders, pronounced pectoral muscles in the case of the males and big, round breasts of the females (See, for example, Figs. 21, 24 and 25). The females even seem to wear a corset that barely contains their curves (For example, see, Fig. 14). At the Alchi Group, careful shading and strokes are used to depict these details (For example, see, Fig. 14). Many of the figures wear the long pearl garlands of the Kashmiri style, which is hung around the shoulders and loops around the arms to end below the knees (See, for example, Figs. 14, 21, 24 and 24). Even ornamental motifs such as a row of geese holding looping strands of pearls in their beaks, and medallions painted with fantastical animal and human figures are typical of the style (See, for example, Fig. 26).

Fig. 24. The carved doorjamb at the Shakti Devi temple, Chatrahri, Chamba, circa ninth century (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Fig. 25. A carved relief, Avantisvami temple, Avantipur, Kashmir, second half of ninth century (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

Fig. 26. Stone carving from Avantisvami temple (photo by Yashaswini Chandra)

[1] The later temples include the Manjushri Temple, the Lotsawa Lakhang ('Translator’s Temple') and the Lakhang Soma (New Temple). The choskhor also includes some Kakani, or gateway, chortens.

[2] It is possible that the site of Alchi continued to provide a safe holding house into the later period, 16th century (Denwood 2014:65–66).

[3] Personal communication.

References

Chandra, Yashaswini. 2007. ‘A Form of Tara Peculiar to Alchi’. Orientations 38.4.

———. 2013. ‘The Evidence of a Goddess: The Cult of Tara, Trade and Patronage in Early Ladakh’. In The Cult of the Goddess in Indian Art, Past and Present. New Delhi: National Museum Institute and D.K. Printworld.

———. 2013. ‘The Mirkula Devi Temple: A Unique Wooden Temple in Lahaul in the Western Himalayas’. Artibus Asiae 73.2.

Denwood, Philip. 1980. ‘Temple and Rock Inscriptions at Alchi’. In The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 2, eds. David L. Snellgrove and Taduesz Skorupski. Warminster: Aris and Philips Ltd.

———. 2014. ‘The dating of the Sumtsek Temple at Alchi,’ in Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-Cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakorum, eds. Erberto Lo Bue and John Bray. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

Goepper, Roger. 1996. Alchi: Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary: The Sumtsek. London: Serindia Publications.

Heller, Amy. 2002. ‘The Silver Jug of the Jokhang’. Online at www.asianart.com/articles (viewed on March 10, 2017).

Karmay, Heather. 1977. ‘Tibetan Costumes, 7th to 11th Centuries.’ Essais sur l’art du Tibet, ed. Ariane Macdonald and Yoshiro Imaeda. Paris: Jean Maisonneuve.

Losty, Jeremiah P. 1982. The Art of the Book in India. London: The British Library.

Luczanits, Christain. 2004. Buddhist Sculpture in Clay: Early Western Himalayan Art, Late 10th to Early 13th Centuries. Chicago: Serindia Publications.

Otto-Dorn, Katharina. 1967. L’art de l’Islam. Paris: Éditions Albin Michel.

Singer, Jane Casey. 1997. ‘The Sublime Image: Early Portrait painting in Tibet’, in First Under Heaven: The Art of Asia. London: Hali Publications Ltd.

Snellgrove, David L., and Tadeusz Skorupski. 1977. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 1. Warminster: Aris and Phillips Ltd.

———. 1980. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 2. Warminster: Aris and Philips Ltd.

Tucci, Giuseppe, and E. Ghersi. 1966 [1933]. Secrets of Tibet: Being the Chronicle of the Tucci Scientific Expedition to Western Tibet. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications.

Whitfield, Susan, ed. 2004. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London: British Library.