Ladakh is situated in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in the Western Himalayas, and is bounded by the Karakoram mountain range in the northwest and by the Great Himalayas in the south. Despite these forbidding natural barriers, Ladakh has several passes and land routes that have historically made the region accessible to the outside world. Its closest neighbours are Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region/TAR of China) to the east, Kashmir to the south, and, in the west, the Northern Areas of Pakistan, which include Baltistan, Nagar (or Nagir), Hunza, Gilgit and Yasin. To the north over the Karakoram passes lies Xinjiang (Chinese Central Asia).

Historically, Ladakh has had trading and military contacts with the above regions, and, ultimately, the land routes also served as a medium through which artistic and cultural influences were exchanged. During the late 7th–early 8th centuries, Ladakh became part of the Tibetan Empire (Yarlung dynasty) and, with the region’s route connections to the west through today’s Baltistan, the Tibetan army was able to reach the westernmost parts of the Taklamakan Desert (Xinjiang). Buddhism was first introduced in the Tibetan Empire in the 7th century and established in the Ladakh region at the latest in the 8th century. The Tibetan language was introduced there perhaps as early as the 7th century (Denwood 1995:281–87, Denwood 2005). However, after the so-called ‘First Diffusion’ of Buddhism in Tibet that began in the 7th century, Buddhism lost official support in the Tibetan regions (including Ladakh) until it was reintroduced in the 10th century and found a permanent foothold (Denwood 2010:189–96). This time around, Ladakh as well as Guge-Purang—by now, two independent kingdoms on the western edge of Tibet[1]—were at the forefront of the revival of Buddhism in the Tibetan regions through Kashmir, as one of the last great bastions of Buddhism in India. The rebirth of Buddhism went hand in hand with an artistic efflorescence in a movement known as ‘Chidar’ or the ‘Second Diffusion’. This cultural movement is exemplified in the so-called ‘Alchi Group of Monuments’, which include the early monasteries of Alchi, Sumda and Mangyu in Ladakh. The art- historically important mural paintings have received international fame and been the subject of much scholarship.

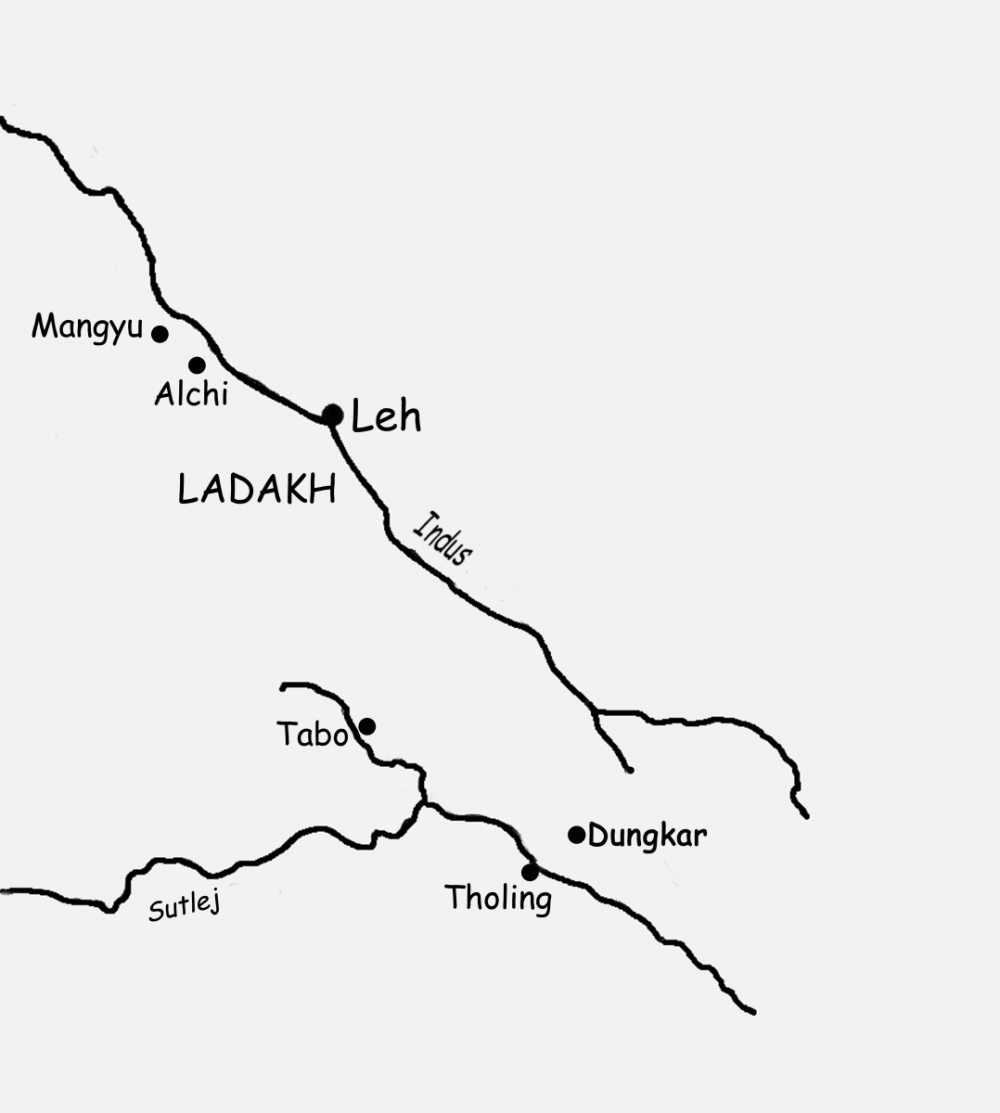

However, a closer look at some of these murals reveal a more complex legacy reflective of the diverse cross-cultural influences on Ladakh, which included but was not restricted to Kashmir. The Alchi choskhor, ‘sacred enclosure’, or monastic complex consists of six temples, and is at the heart of a mid-size eponymous village (Fig. 1). It lies at an altitude of about 3,250 meters and is situated in a valley of the same name, near the south bank of the Indus River (Map). The capital Leh is circa 60 km to the southeast of Alchi on the northern side of the Indus. Art-historically—and, indeed, historically—the most interesting murals are perhaps in the earliest temple on the site, the Dukhang (the Assembly Hall), which dates to the first half of the 11th century, and also in the slightly later Sumtsek (a three-tiered temple) (Fig. 1). Typical of the early Second Diffusion temples, the Buddhist artistic programme both in the Dukhang and in the Sumtsek is executed according to the Vairochana cycle, consisting of mandalas (Fig. 2) and magnificent depictions of Buddhist deities.

Map

Fig. 1: Alchi Choskhor or Monastic Complex (photo by Christian Luzcanits 2000, ©Western Himalayas Archive Vienna [WHAV])

Fig. 2: Alchi Sumtsek, first floor, back wall (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

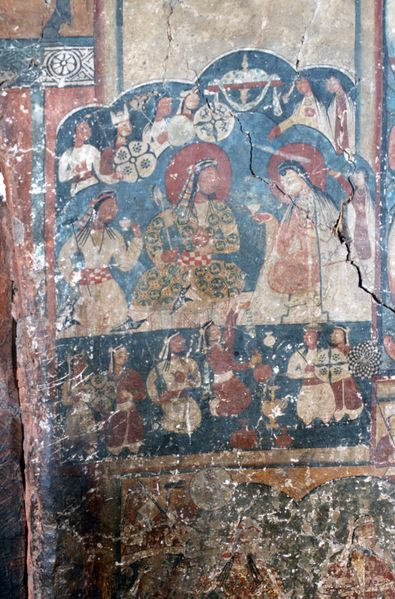

Although the murals in the Dukhang and the Sumtsek follow the Buddhist pantheon, both temples also have non-Buddhist scenes that form part of the artistic programme. In the Dukhang, there are several secular murals on the eastern left wall, of which the so-called ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ (Fig. 3) is perhaps the best known as it has been previously published (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1977). The mural is a foundation scene as it is situated near the entrance to the Dukhang and was painted at the time when the temple was built. Later examples of foundation scenes can be found in temples in Spiti in Himachal Pradesh such as Drangkhar, Nü and Luk (Tucci and Ghersi 1933:51, 105, 114) and Tsaparang in western Tibet. They depict local Tibetan women in long processions, rows of monks and laypersons, and kneeling men and women giving offerings to a deity.

Fig. 3: Alchi Dukhang (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

As the written sources for Ladakh’s early medieval history (10th–12th centuries) are particularly fragmentary, the secular murals at Alchi are important for attempting to form a picture of Ladakh’s historical background. The ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ depicts a cup rite between a man and a woman, in which the woman is offering a drinking vessel to a centrally seated man, to whose right a kneeling man also holds a cup (Fig. 4). Standing subsidiary men and women flank the three central figures. The lower part of the drinking scene depicts yet more men, some of whom are armed, amid drinking vessels (Fig. 5). Non-Buddhist themes are not commonly found in Tibetan temples and thus the portrayal of drinking scenes at Alchi seems to have a specific cultural meaning in the history of the region.[2]

Fig. 4: Alchi Dukhang (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

Fig. 5: Alchi Dukhang (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

The iconography of the drinking scene in the Dukhang at Alchi offers a rare glimpse into secular life and especially court customs in 11th-century Ladakh. The high status of the seated man and the woman may be assumed by the haloes around their heads, which in Tibetan art are reserved, in addition to Buddhist deities and important monks, for secular people thought to be worthy of the divine.[3] The female participants in the mural can be deemed Tibetan by their costumes and hairstyle. The woman offering the cup is wearing a dress with a square neckline, which is very similar to today’s local Ladakhi female costume called sul ma (Ahmed 2002:111). The Alchi dress differs somewhat, however, from the female costume portrayed in the mid–11th-century murals in the Assembly Hall in the Tabo monastic complex in Spiti (Lahaul-Spiti, Himachal Pradesh), where the women’s attire is a round-necked dress with an ample white cape with blue trimmings (Map; Fig. 6, the figure on the right), and from the v-necked plain dress covered by a red or white cape with contrasting trimmings on the edges depicted in Tholing monastery in Guge (western TAR) and also dating to the 11th century.[4] Both the shape of the dress and the cape portrayed at Tabo and Tholing are derived from the ancient Tibetan Yarlung dynasty costume.[5] The short thick boots, portrayed on women at Alchi and Tabo are also typically Tibetan and this type of footwear is worn even today across the Tibetan Plateau.

Fig. 6: Tabo Dukhang (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 2001, courtsey WHAV)

The hair of the cup-offering woman in the Dukhang is braided in multiple thin plaits, which are entwined with strands of blue stones; similar strings of jewellery are also visible around her neck (Fig. 4). The blue stones are likely to be turquoises, which are highly valued and continue to be worn by Tibetans and Ladakhis in modern times. The big blue ornament placed on the centrally seated woman’s forehead resembles a perak, a headdress worn by today’s Ladakhi women.[6] Identical hairstyles are also depicted on the women in the 11th-century murals at Tabo and Tholing (Fig. 6). The tradition of wearing plaited hair that is entwined with turquoises still continues among the women in eastern Tibet (Clark 2004:91). The woman and the attending females in the Dukhang mural can thus be deemed Tibetan; furthermore, their attire including hair ornaments, jewellery and footwear shows historically remarkable unity and continuity in the Tibetan cultural context.

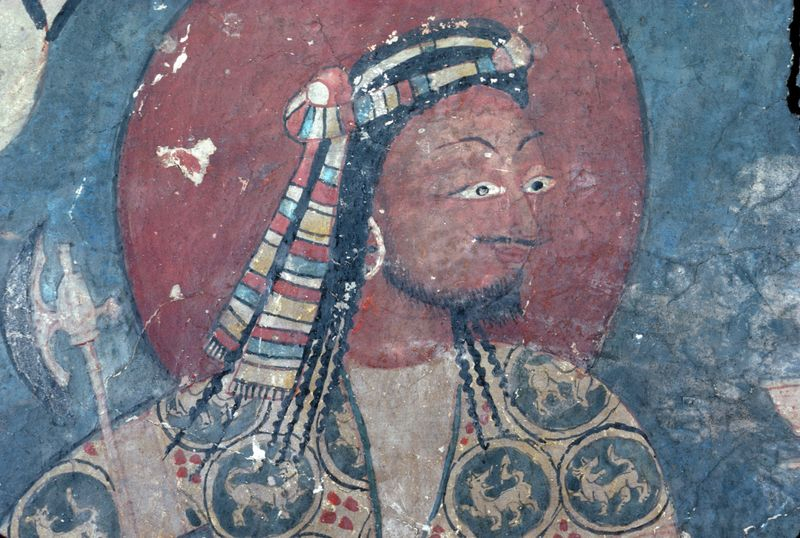

In contrast, the central man in the ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ has physiognomic features not normally associated with the portrayal of Tibetan men, such as a moustache, a goatee beard and long, thick curling strands of hair (Fig. 7). He holds an axe in his hand and a dagger hangs from his belt. He is wearing a long-sleeved caftan with a deep v-neck, whose fabric has elaborate motifs of four-legged creatures and is also ornamented with armbands (Figs. 4 and 7). The armbands formed part of the Turkic costume in pre-Islamic Central Asia and were later popular with Turko-Islamic peoples such as the Ghaznavids and the Seljuqs. The outfit of the central man is comparable to Turkic steppe costume, designed for horse riding. His close-fitting caftan, decorated with motifs, differs from the traditional Tibetan men’s outfit, which is plain and loose (Fig. 6, Tabo Assembly Hall, the two men dressed in brown robes and the man in a white costume in the middle). Some of the male attendants in the mural have a similar hairstyle and headband as on the central man (Figs. 7 and 5), while others have multiple thin plaits (Figs. 4). Thus, we can see a clear attempt by the artist to contrast different hairstyles and costumes. The multiple thin plaits depict a Tibetan men’s hairstyle; they are also portrayed on the men in the murals of the Assembly Hall at Tabo (Fig. 6). The long, thick curling strands of hair and the headbands in the ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ compare to Turkic hairstyle and headdress, depicted in pre-Islamic Central Asian arts[7]and later in Islamic arts, for example, on Seljuq ceramics. Thus, the centrally seated man and some of his attendants in the Dukhang can be deemed Turkic by the way their attire and hair are portrayed by the artist.

Fig. 7: Alchi Dukhang (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1983, courtsey WHAV)

Certain aspects of the iconography of the ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ are alien in Tibetan artistic representation, but references to them can be found in Turkic and Turko-Islamic cultural contexts. Turkic literary texts attest to a long tradition of cup rites during feasts and marriage ceremonies, and women with hennaed hands are mentioned in connection with a marriage feast in the Turkic epic Dede Korkut (Lewis 1974:69)[8] which was compiled during the 15th century from the much earlier pre-Islamic oral tradition of the nomadic Turks from the steppes. The iconography of the ‘Royal Drinking Scene’ suggests a ceremony between a foreign man and a Tibetan woman, where she is showing her allegiance to the man amid onlookers of Tibetan women and armed, mainly non-Tibetan men. A very similar scene of a cup offering, also dating to the 11th century, is portrayed in the Vairochana Assembly Hall at Mangyu (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Mangyu Dukhang (photo by Christian Luzcanits 1994, ©WHAV)

The Sumtsek or the three-tiered temple is decorated with sumptuous Buddhist mandalas and deities, but there are also murals of historical scenes on the ground floor, which continue the theme of drinking found in the Dukhang. In Fig. 9, two women clad in Ladakhi costumes are seated on either side of a bearded man and one of the women is making a cup offering to him. The man’s central position in the composition and his sumptuous robe[9] denote his high status, and the cup he is holding further identifies him as a ruler. The cup-holding man is a well-established iconographic motif that symbolises the ruler, seated among his subjects in a courtly setting. Standing or seated women and men flank the three central figures, and, in the lower scene, a male cupbearer is offering yet another drink to the couple above, accompanied by seated men. A covered offering table and ewers are placed on the ground. The attendant men all wear v-necked belted caftans, a few of which are ornamented with armbands, and their headgear is either a long striped scarf as in the Dukhang mural, or a pointed hat. Some of the men’s attires also include a cape. The female attendants are dressed in Ladakhi costumes, which are a more elaborate version of the ones depicted in the Dukhang. The robe has a black undergarment and a square neckline trimmed with colourful stripes. Similar stripes decorate the ends of the sleeves and the hem, and both women wear white capes with patterned edges. Several necklaces are placed around their necks, and the cup-offering woman has her hair in a long plait, adorned with small pieces of jewellery. The artist has again clearly distinguished between different types of costumes and headgear, and is seemingly portraying a historical event.

Fig. 9: Alchi Sumtsek (Courtesy Lionel Fournier)

The focus in Fig. 10 is on the previously portrayed lady, who is this time accompanied by two men, one of whom is a Buddhist monk and the other a layman in a black costume and white cape. All three participants are seated cross-legged and the woman has a conch shell in one of her hennaed hands (Fig. 11). A transparent black scarf, which in turn is covered by a long stripy scarf, seemingly holds the woman’s hair in place and, although she wears a Ladakhi dress, her covered hair suggests she might be a foreigner or following foreign customs in her attire. Her footwear, black embroidered boots tied at the ankles, also differs from the white felt boots seen on the Tibetan women, but is identical to that of the men wearing caftans and headbands in the mural. To the right of her, yet another drinking scene is depicted (Fig. 10). The woman offering a cup to the man dressed in a patterned caftan and wearing a tall hat are seemingly the same as those portrayed in Fig. 9. Jugs and drinking vessels are scattered on the ground, and, in the lower scene, men dressed in caftans and wearing headbands hold out cups around a covered offering table. In Fig. 10 the focus is on the Buddhist ideal, represented by the woman holding a conch shell and the seated monk, and the scene was perhaps painted to mark the occasion of consecrating the temple. However, despite the emphasis being on Buddhist aspects in the Alchi murals, the drinking rites form a major part in the secular scenes and thus demonstrate the patrons’ wishes to be portrayed in such a manner.

Fig. 10: Alchi Sumtsek (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

Fig. 11: Alchi Sumtsek (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1983, courtsey WHAV)

The style of painting in the Sumtsek is influenced by Indian Pala and Kashmiri artistic currents. The Pala style of painting is especially notable on the depiction of the protruding outer eye, a defining feature that is used frequently in the artistic representation both in the Dukhang and the Sumtsek (Figs. 4, 5, 7, 11). The projecting outer eye portrayed in a three-quarter profile was derived from the Indian tradition of painting, where its beginnings can be detected in the Ajanta cave paintings (Behl 1998:76, 86, 143), and later it was widely used in the 11th- and 12th-century Pala Buddhist manuscripts and also in Jain manuscript illustrations. The projecting outer eye also forms part of the figural portrayal both at the Entry Hall (996 CE; Fig. 12) and Assembly Hall (1046 CE; Fig. 6) at Tabo, as well as the western Tibetan monastic sites of Tholing and Mangnang.[10]

Fig. 12: Tabo Gokhang (photo by Christian Luzcanits 1994, courtsey WHAV)

The eastern Indian manuscript painting tradition has also directly influenced the portrayal of a horse in a royal hunting scene painted on the dhoti of the gigantic four-armed clay sculpture of Avalokiteshvara in the Sumtsek (Fig. 13). The Pala depiction particularly matches the movement of the horse’s legs and the pearl ornament around its neck in Fig. 13 (Losty 1982:Plate V). The tradition of placing Buddhist images inside architectural frames is also frequently observed in the Pala Buddhist manuscripts and on Buddhist phyllite stelae from eastern India. Shrines with trefoil or cinquefoil arches are commonly portrayed in the Sumtsek murals, and are comparable to those found in Pala Buddhist manuscripts. For example, in Figs. 9 and 10, ornate wooden architectural trefoil and quatrefoil arches embellished by jewels and textiles are painted in the background. In addition to these eastern Indian artistic influences, Tibetan architectural details are also used in the Sumtsek murals, thus combining both foreign and local elements (Goepper 1996:136–37, 144–45).

The artists in the Sumtsek used extensive highlighting and shading in their portrayals of Buddhist deities. Green Tara (Fig. 14) is a noteworthy example of these techniques applied on her skin, which give the image depth and movement. The Pala feature of the protruding outer eye is particularly dominant on the deity, and there are also strong influences from the Kashmiri artistic tradition in metal sculpture such as the way Green Tara’s contracting stomach muscles are depicted, and the long scarf and the garland-type necklace around her body. These features form an essential component of the portrayal of many other Buddhist deities in the Sumtsek.

Fig. 14: Alchi Sumtsek (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1981, courtsey WHAV)

The secular scenes at Alchi also include distinct Turkic iconographical details whereby the role of particular individuals in the murals can be determined by their special attributes: the cupbearer holds a cup, the soldiers have weapons and the falconer carries a bird (Fig. 13). This type of portrayal is typical in Turkic artistic representation, as are sumptuous costumes. Different textile motifs also form an important part of the artistic programme in the Sumtsek, and they are depicted frequently on deities and on people. The ceiling of the Sumtsek is decorated with painted panels imitating textiles, where, for example, the pearl roundel is used as a framing device for many of the motifs.[11] In addition to drinking and feasts, the theme of hunting is strongly represented at Alchi. In the Dukhang, a mural depicts hunters on horseback holding bows and arrows, and a very similar scene can also be found in the lower level of the mural at Mangyu (Fig. 8). Falconers are depicted among the crowds of attendants in both drinking scenes in the Sumtsek, identifiable by the bird on their arm. Men hunting on horseback are portrayed on the aforementioned dhoti of the gigantic Avalokiteshvara, and the theme of hunting continues in the ceiling in the Sumtsek, where painted panels depict an archer riding a horse or an elephant.

Fig. 13: Alchi Sumtsek (photo by Jaroslav Poncar 1989, courtsey WHAV)

Hunting, cup rites and feasts are themes that do not form part of the artistic representation in the context of Tibetan temples and art generally. They are topics that relate to court life and, essentially, portray the power of the ruler in a courtly setting. These princely themes are commonly found in Islamic arts although their origins are in pre-Islamic Iran (Sims 2002:40). It may be assumed the drinking scenes at Alchi were influenced by the pre-Islamic Turkic culture from the steppes rather than by the urban Islamic tradition. The drinking scene in the Dukhang shows an armed foreign man in the centre of the composition, accompanied by his soldiers and performing a cup rite according to non-Tibetan customs. The Tibetan woman offers him a cup in an act of allegiance, which could be marital. The setting in the Sumtsek is more sumptuous but, essentially, the portrayal is of a ruler accompanied by drinking rites. These secular murals at Alchi record important historical events from the region’s past, and offer us a glimpse into a poorly documented era in Ladakh.

[1] Ladakh and Guge-Purang previously formed independent kingdoms and are now part of separate nation states, but are collectively referred to as western Tibet in the cultural sense.

[2] Although Tibetan written sources offer no evidence for cup rites, the Tibetan legendary epic Gesar refers to a cup rite on the occasion of the enthronement of Gesar when he is offered a drink of pure nectar by his fiancée (Stein 1956:137–38).

[3] According to Jane Casey Singer, haloes are commonly seen in Tibetan portrayals of royal, noble and saintly figures (Singer 1997:128).

[4] See Zla ba tshe ring 2000:237, plate 142, for the 11th-century women’s dress depicted on the north-western stupa at Tholing.

[5] For a discussion on the ancient Tibetan costume, see Karmay 1977 and Heller 2002.

[6] See Clarke 2004:21 for such a headdress.

[7] Turks with long thick plaits are portrayed as early as mid-7th century in a Sogdian mural in Afrasiab in Samarqand, today’s Uzbekistan. See Whitfield (2004:111).

[8] The epic also describes the infidel (non-Muslim) female cupbearers as having their hands dyed with henna (Lewis 1974:42, 88).

[9] The king has been heavily repainted although part of his original costume has survived.

[10] This artistic feature can also be found in Central Tibet, for example, at the temples of Yemar and Drathang.

[11] See Goepper 1996, for the painted textiles on the ceiling.

References

Alafouzo, Marjo. 2008. 'The Iconography of the Drinking Scene in the Dukhang at Alchi, Ladakh'. PhD thesis. Department of the History of Art, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (SOAS).

Behl, Benoy. 1998. The Ajanta Caves. Ancient Paintings of Buddhist India. London: Thames and Hudson.

Denwood, Philip. 1980. ‘Temple and Rock Inscriptions at Alchi’. In The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 2, eds. David L. Snellgrove and Taduesz Skorupski. Warminster: Aris and Philips Ltd.

———. 1995. ‘The Tibetanisation of Ladakh: The Linguistic Evidence.’ Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5. Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia on Ladakh, eds.Henry Osmaston and Philip Denwood. London: SOAS.

———. 2005. ‘Early Connections between Ladakh/Baltistan and Amdo/Kham.’ In Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives, eds. John Bray. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

———. 2010. ‘Tibetan Arts and the Tibetan “Dark Age”, 842–996 CE’, Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 5.

———. 2014. ‘The dating of the Sumtsek Temple at Alchi,’ in Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-Cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakorum, eds. Erberto Lo Bue and John Bray. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

Goepper, Roger. 1996. Alchi: Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary: The Sumtsek. London: Serindia Publications.

Heller, Amy. 2002. ‘The Silver Jug of the Jokhang’. Online at www.asianart.com/articles (viewed on March 10, 2017).

Karev, Yuri. 2005. ‘Qarakhanid Wall Paintings in the Citadel of Samarqand: First Report and Preliminary Observations.’ Muqarnas 22.

Karmay, Heather. 1977. ‘Tibetan Costumes, 7th to 11th Centuries.’ Essais sur l’art du Tibet, ed. Ariane Macdonald and Yoshiro Imaeda. Paris: Jean Maisonneuve.

Lewis, Geoffrey, trans. 1974. The Book of Dede Korkut. London: Penguin Books.

Losty, Jeremiah P. 1982. The Art of the Book in India. London: The British Library.

Luczanits, Christain. 2004. Buddhist Sculpture in Clay: Early Western Himalayan Art, Late 10th to Early 13th Centuries. Chicago: Serindia Publications.

Sims, Eleanor. 2002. Peerless Images: Persian Painting and its Sources. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Singer, Jane Casey. 1997. ‘The Sublime Image: Early Portrait painting in Tibet’, in First Under Heaven: The Art of Asia. London: Hali Publications Ltd.

Snellgrove, David L., and Tadeusz Skorupski. 1977. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 1. Warminster: Aris and Phillips Ltd.

———. 1980. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, vol. 2. Warminster: Aris and Philips Ltd.

Stein, R. A. 1956. L’épopée tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version Lamaique de Ling.

Tucci, Giuseppe, and E. Ghersi. 1966 [1933]. Secrets of Tibet: Being the Chronicle of the Tucci Scientific Expedition to Western Tibet. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications.

Whitfield, Susan, ed. 2004. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London: British Library.

Zla ba tshe ring, ed. 2002. Precious Deposits: Historical Relics of Tibet, China, vols I–V. Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers.