During the rule of the Solankis (also known as the Chalukyas) in Gujarat, many grand monuments were built between the 11th and the 12th centuries CE. The surviving monuments include temples at Somnath, Modhera, Sidhpur Patan, reservoirs such as the Sahasraliṅga Talav at Patan Anhilwad, and stepwells such as the Ran-ki-Vav, to name a few. (Dhaky 1961:passim).

The Ran-ki-Vav[1] or ‘Queen’s stepwell’ is situated in Patan, which was the medieval capital of the Solanki empire, located 125 km north of Ahmedabad. The stepwell, a sacred memorial built entirely below ground level, is one of India’s unique contributions to the architectural heritage of the world, and UNESCO has recognized it as such in 2014.

Stepwells were developed in the arid region of Gujarat and Rajasthan in Western India. In their earliest forms, nothing more than plain dressed stones protected the sides of the sandy pit, hence the underground passage was kept as short as possible. Gradually, architects devised the means to strengthen these structures and the corridors were expanded vastly in length and width. Other developments included landings at regular intervals, pavilions with multiple storeys, and stepped passages, which to begin with were only a practical adjunct to the wells but later acquired a character of their own. In this way, the humble village well, that ubiquitous sign of human habitation, transformed itself into a strikingly original and complex architectural form.

Since the construction of watering places was considered to be a meritorious act, especially to commemorate the dead, innumerable stepwells were built over the centuries in western India. In the barren and the featureless landscape, these subterranean structures with their ornate interiors make a strong impact on the mind of the visitor who chances upon them.

Fig. 1: Ran-ki-Vav Stepwell, Patan

The Ran-ki-Vav (Fig. 1) was built during the third quarter of the 11th century by Queen Udayamati as a memorial to her husband, the Solanki king Bhīmadeva I, who during his reign had built the great Sun-Śiva temple at Modhera[2]. The Ran-ki-Vav stepwell is amongst the largest in Gujarat, and in terms of its sculptural wealth surpasses all others.

The stepwell faces the east and possesses all the four principal components of a fully developed structure of its type. These are: a stepped corridor beginning at ground level and leading down to the underground masonry reservoir (kuṇḍa), compartmented at regular intervals by multi-storeyed pillared pavilions; a draw well at the rear end (Fig. 2); and a large reservoir for collecting the well’s surplus water, located between the stepped corridor and the well. At the head of the monument, at ground level, there was a toraṇa or ornamental arch, a ceremonial freestanding gateway often seen in Gujarat, which is no longer there. The length of the stepwell measured at ground level of the toraṇa to the far side of the well is about 65 metres, or 213 feet. The four intervening pavilions, which demarcate the stages along the descent, has an increasing number of storeys with the roof of the top storey of each of the pavilions reaching up to the ground level.

Fig. 2: Interior of the Ran-ki-Vav Stepwell

The sheer scale of the stepwell is remarkable in terms of size, profusion of sculpture and quality of workmanship. The sculptures enhance the corridor’s walls, the pavilions and, exceptionally, even the inner circumference of the well itself. The large images alone, even in the stepwell’s present ruined state, number some 400. Had all the seven levels of the monument been fully furnished with all of their planned sculptures, the total number would certainly have been at least 800.

Ran-ki-Vav has suffered extensive damage in the past. There is evidence that repeated flooding of the Sarasvati River brought down the upper parts of the structure leaving heavy deposits of sand. Then, in the early 19th century, entire pillars and structural components of the upper storeys of the pavilions which had collapsed but did not get buried under sand were carted away by the owner of the land at the time and used in a new stepwell known as the Barot Vav in Patan itself. Submerged by the river’s periodic deposits and despoiled of its visible remains, Ran-ki-Vav underwent neglect and although its existence was known of, it received little attention over the following century.

Since the 1980s, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has carried out desilting of the monument, realigned the walls and structural parts and reset the surviving sculptures. The stepwell originally consisted of seven storeys or terraces, though only five survived; the upper terraces as seen today have been extensively restored by the ASI.

The Method of Construction

Commissioned by no less a person than the queen Udayamati, mother of the monarch Karṇadeva, who was known for his vast territorial possessions and continuously expanding wealth; Ran-ki-Vav was the most ambitiously conceived stepwell of its time. Its design and execution must have called forth all the experience and resourcefulness at the disposal of its builders.

As stepwells were subterranean structures, their builders were confronted with unique problems not encountered in the construction of temples and other monuments. The builders were required to dig a trench, construct an underground staircase to the bottom of the well, and to build strong embankments against the sides of the trench in order to protect this path from the sandy soil of Western India. After much experimentation through the centuries—during which hundreds of stepwells were built—by the 11th century architects had perfected a design and a simple but efficient method for constructing these underground structures.

The architects included various measures to make the monument strong, such as the introduction of a buffer structure of bricks behind the walls to withstand the pressure of the soil. Thus, the visible stonewall of the monument is only 45 cm thick and is actually a veneer that is secured by the hidden brick support. The builders broke up the deep walls on the two long sides to create a series of stepped terraces and provided for baulks or buttresses at regular intervals, which were later converted into the pillared pavilions. In this way, a deep terraced trench, rectangular in shape with internal divisions of four smaller interconnected compartments was constructed. The advantage of this ‘stepping down’ was that it effectively reduced the height of the wall, thus minimising the risk of collapse. Also, the steps provided a foothold and working space for the builders (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: High Wall

Eventually four multi-storeyed pillared pavilions were built in the space that became available when the baulks were removed, By means of placing a basal course on each terrace, vertical panels at regular intervals above and a crowning course over these vertical panels, niches were created on each terrace to accommodate divine images (Fig. 4). The well shaft was dug beyond what was to be the fourth pavilion, the work on the shaft probably proceeding at the same pace as on the other parts since it was adjunct to them.

Fig. 4: A Wall Section

The architecture of the stepwell

An easily manageable descent from the ground level to the bottom of the well was an essential part of a well-designed stepwell. In the Ran-ki-Vav, in addition to the main flight of steps from the ground to the reservoir, supplementary stairs provided access from the seventh to the fourth storeys. These supplementary staircases between the higher storeys obviated the need to walk around the entire monument every time one wanted to reach a lower storey from a higher one. Small, pyramid-like turreted steps attached to the main stairs—doubtlessly an influence from the architectural styles of Rajasthan—further imparted a pleasing and harmonious effect to the whole construction.

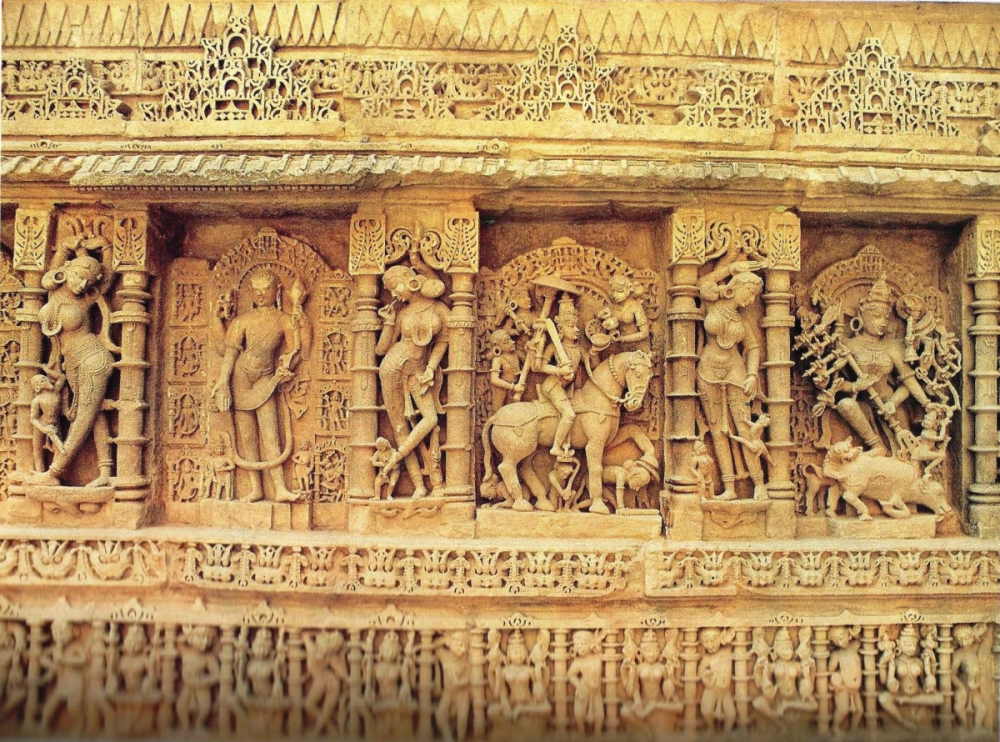

The central zone on each terrace, with alternating projecting panels and sunken niches, is the principal repository of sculpture. The niches on the walls of the corridors (as also on the pavilions) are occupied by figures of the deities of Hindu pantheon, while the projecting pillared panels portray apsarās (celestial women) and other figures.

There were 292 pillars in the pavilions, out of which 226 still remain, some are fully intact while others only partially so. Even though the first two stages and pavilions are badly damaged, a visitor may observe the architectural details of the stepwell from the third stage where the walls, including the apsarās and the deities in the niches, are well preserved.

The masonry tank (kuṇḍa) attached to the well to receive its surplus water through the fourth pavilion was planned on a scale befitting the rest of the monument. Some other stepwells (e.g., Adalaj near Ahmedabad) have similar reservoirs to collect excess water from their wells but Ran-ki-Vav’s reservoir is the largest amongst all the other stepped wells of Gujarat. The rectangular tank measures seven metres east to west, and six metres north to south, and is a little less than three metres deep from the floor of the third pavilion that gives access to it. The reservoir’s significance as a large, independent architectural member of the stepwell is clearly evident. Its floor is paved with smooth slabs. Apart from the main steps from the rear of the third pavilion, turret-shaped steps lead down to the water from the northern and southern sides. Numerals and vertical markings engraved for the alignment of slabs in the reservoir testify to the care that went into its construction.

An interesting feature of the monument as a whole is the presence of hundreds of masons’ marks on various parts of the stepwell. These marks, which are found on some other monuments as well, served the practical purpose of helping identify the artisans or their guilds, in order to settle their dues at the completion of work.

The reservoir facing the well stands in a pit and is at the lowest level of the corridor; high walls of about 15 metres flanking it on either side. Realising that its depth could affect the structure’s stability, the builders introduced additional measures such as a two-storey high ‘bracing structure’, which was quite likely an afterthought. This two storeyed structure built into the bed of the reservoir consists of a frame of pillars and beams to strengthen the walls on both the northern and southern sides. The pillars of this structure are identical to the pillars elsewhere in the Ran-ki-Vav, from which we can conclude that no great interval of time intervened between the building of this structure and the rest of the monument.

There are visible signs that this intervention was an unplanned one: the steps leading down to the floor of the reservoir were cut arbitrarily to accommodate this structure and the niches in the lowest course could not be filled up. Thus, although the builders had designed an imposing setting for the reservoir facing the well, the bracing structure made it impossible to view this basin in its entirety from any spot. Despite the provision of as many as 10 niches on the lowest terrace (on both the south and north walls) and the niches in the centre on either wall being offset by means of prominent frames (corresponding to similarly framed niches higher up the stepwell), the niches themselves are totally obscured by the pillared structure.

The first three pavilions have suffered damage. The fourth pavilion, fronting the well, is the final portion of the long corridor and is almost an adjunct to it. The floor of the corridor is at its deepest in the reservoir; hence, this adjoining pavilion at the rear end of the monument, where as many as seven storeys were planned, had the greatest height (or depth, which in this case is the same thing) of all the pavilions. For the same reason that prompted the builders to add a bracing structure—the fear that the structure might not be able to withstand the weight of the high walls—for the fourth pavilion the builders filled up the interspaces between the columns in the three lowest floors.

The well

The draw well, situated at the western extreme of the stepwell is the raison d’être of the whole complex structure. It is imposing both for its depth of more than 28 metres, as well as for its diameter, which is 10 metres at the top. Sculptures girdle its inner circumference, which is a unique feature in a stepwell (see below, and the allied article). All stepwells are fed by rivers; Ran-ki-Vav was supplied by the river Sarasvati flowing about 500 metres to its north. The well’s shaft is divided into seven levels, three of them terraced, their diameter diminishing as the depth increases. Three channels in the lowest storey drain the well’s surplus water into the reservoir.

The sculptures

At Ran-ki-Vav, large sculptures, which may originally have been as many as 800, and a countless number of smaller figures, decorate the corridor and the well itself. Each terrace was organized into three horizontal zones, of which the broad median band was reserved for large sculptures. These were either in the form of projecting panels or sunken niches.

The major sculptures are broadly of two kinds, one comprising deities in niches and the other consisting of figures such as apsarās and the regents of the directions (dikpālas) carved on the upright posts. Both categories feature an equal number of sculptures. In this article the sculptures of the major deities are discussed, while the sculptures of apsarās will be considered in an allied article.

There are nearly 400 niches on the monument and within these, the sculptures depicting two divinities, Viṣṇu and Pārvatī, outnumber all others. Viṣṇu as Nārāyaṇa is intimately associated in mythology with cosmic waters: wells, tanks and reservoirs used to be consecrated to him. Sculptures of Viṣṇu reclining on Śeṣa, the mythical serpent, were installed in such a way that the surface of the reservoir’s water became a part of the theme and indicated the primal substance in which Viṣṇu reposes at the beginning of Creation. At Ran-ki-Vav too, the Śeṣaśayana form of Viṣṇu Nārāyaṇa figures in many prime positions. Viṣṇu Nārāyaṇa is also depicted in other forms, including his avatāras (incarnations) and his 24 forms (Caturviṁśatimūrtis). The other major divinity depicted here is Pārvatī, because of the commemorative nature of the monument. This aspect will form part of an allied article.

The first two stages of the corridor, together with the pavilions, are greatly ruined. Hence, it is only as one enters the third stage that one is face to face—literally—with the sculptures. As we can consider and illustrate only a small number of images here, for detailed descriptions, please refer to Mankodi 1991 and Mankodi 2012.

The avatāras

In Puranic mythology, God Viṣṇu assumes avatāras or incarnations for the good of humankind. Seven out of Viṣṇu other avatāras found at the Ran-ki-Vav are: (1) Varāha or Boar, (2) Vāmana or the Dwarf, (3) Rāma, (4) Balarāma, (5) Paraśurāma, (6) the Buddha and (7) Kalki. The niche for the Narasiṁha or Man-Lion avatāra is empty. Independent sculptures of the Matsya (Fish) and Kūrma (Tortoise) incarnations were not represented during this period in Gujarat, therefore, their absence here is hardly surprising.

The series of the avatāras, all rendered in strikingly original forms, begins with Varāha on the wall facing the south, and ends with Kalki on the opposite wall.

(1) Varāha (Fig. 5): This avatāra has a human body and a boar’s head. He strikes a heroic pose as he lifts the earth-goddess out of the ocean. Varāha’s natural right hand rests besides his body while his rear right hand holds a mace. His upper left hand supports a discus in the palm and the natural left hand holds a conch.

Fig. 5: Varahā Avatāra

(2) Vāmana (Fig. 6): Vāmana, who appeared in the court of the Daitya (‘demon’) King Bali to reclaim the supremacy of the gods, is a plump acolyte depicted in a loincloth. He has a scarf thrown over his shoulder and is adorned with simple ornaments, which include large earrings. Vāmana has only two hands, his right hand holds a rosary and forms the gesture of blessing, and the left hand is holding an umbrella. His close-cropped hair is tightly curled; his chest displays the śrīvatsa mark, revealing that the cherubic boy is really none other than Viṣṇu.

Fig. 6: Vāmana Avatāra

(3) Rāma (Fig. 7): This is an unusual four-armed figure of Rāma, hero of the Rāmāyaṇa, holding in his hands an arrow, a sword, a shield and a bow. Four-armed sculptures of Rāma are rare, and none is known with attributes similar to this sculpture.

Fig. 7: Rām Avatāra

(4) Balarāma (Fig. 8): This avatāra is standing with a slight bent, with his weight balanced on the left foot. In his four hands, he bears a plough, a lotus, a pestle and a citron. Śeṣa, his snake patron, spreads his three jewelled hoods overhead.

Fig. 8: Balarāma Avatāra

This is one of the few independent representations of Balarāma known from Gujarat, and it exemplifies the traits that contributed to the make-up of the deity. While Balarāma is an incarnation of Viṣṇu, he is also a partial manifestation of Śeṣa or Ananta, the mythical snake, hence the snake hoods over the head. However, one singular attribute of the god found in Balarāma’s representations elsewhere in Northern India is not seen here. A flask of wine often features in Balarāma’s hand since ancient times, and even such an early authority as Varahamihira of the sixth century mentions it (Bṛhatsaṁhitā 57.36), but here the innocuous citron fruit replaces it (Joshi 1979:35–36).

(5) Paraśurāma: The brahmanical hero, who destroyed the Kṣatriya race 21 times over, is standing with a single bend in his body, carrying in his four hands an axe (paraśu), an arrow, a bow and a fruit.

(6) Buddha (Fig. 9): This unique sculpture has a slender form befitting that of an ascetic. He is standing with his body slightly bent, in a short loincloth and an upper garment, a coarse cotton sash slung across his chest, a rosary around his neck, and a long garland down to his ankles. He has curly hair and a slight protuberance on the crown of his head signifying his superhuman character. His earlobes are so long that they almost touch his shoulders, which is one of the 32 traditional marks of great men (mahāpuruṣalakṣaṇas). His coarse garments bring out Buddha’s ascetic aspect vividly. In his four hands he holds two rosaries, a lotus and the edge of his robe.

Fig. 9: Buddha Avatāra

Buddhism had disappeared from Gujarat many centuries before Ran-ki-Vav was built, and the sculptors were no longer familiar with the iconography related to the Buddha. Hence, his form here differs from the traditional Buddha image (Mankodi 1991:103fn).

(7) Kalki (Fig. 10): The incarnation that Viṣṇu is believed to be assuming in future to destroy evil is represented here as a warrior and a sovereign ruler. Some of his warrior characteristics are: he is riding on horseback wielding a sword, armed with a dagger tied at his waist, clad in high protective boots, and sparse ornaments and trampling his adversaries. His royalty is evidenced by his tall crown as well as his being shielded by a parasol and fanned by a female attendant. Kalki has four hands, three of which display a mighty arsenal: a sword, a mace and a discus; but his left front hand is intriguing, for in this hand Kalki holds a bowl into which the attendant pours out from a pitcher. The horse is caparisoned, and his reins rest over the left wrist of the hero’s left hand.

Fig. 10: Kalki Avatāra

The third stage of the corridor had other sculptures besides Viṣṇu’s incarnations, some of which are there in their niches.

Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Fig. 11): Durgā’s violent form strikes an aggressive pose, planting her left leg on the ground. She wields in her 10 right hands a trident, thunderbolt, arrow, mace, goad, spear, discus, lotus, kettledrum and sword. In her 10 left hands she holds a shield, bell, skull cup with a fish, three-headed cobra, war horn, bow, noose, the demon’s hair and the shaft of the trident. The buffalo is shown to be buckling under her thrust, his tongue hanging out, and his human form, wielding a sword and shield, emerges to continue the combat. Durgā’s lion attacks him from the rear.

Fig. 11: Durga killing the buffalo demon

Bhairava (Fig. 12): This niche houses a twenty-armed dancing Bhairava. His eight discernible right hands display a dagger, the gesture of striking or slapping, a thunderbolt, a baton, a kettledrum, a sword and a cobra. The 10 left hands have the tail of the cobra held in the right hand, the gesture of striking, a shield, a threatening gesture, an indistinct object, a noose, a goad, a skull bowl with a fish, and a human head. His wild dog is mauling a decapitated corpse and is reaching up to lick the blood oozing from the freshly cut head in the deity’s hand.

Fig. 12: Bhairava

However, even in this relatively well-preserved part of the monument, only about half the numbers of original sculptures are preserved. From the surviving sculptures on the terrace above the avatāras, it appears that the terrace was consecrated to forms of the Devīs (goddesses), two of whom, Cāmuṇḍā and Gaurī, remain.

The next major repository of sculpture is on the high walls of the reservoir. Prominent among them are the 24 aspects of Viṣṇu (Caturviṁśatimūrtis) and the 12 Gaurīs (Dvādaśagaurīs), which dominate the walls on the north and south. The twenty-four forms of Viṣṇu are where Viṣṇu’s four attributes, conch shell, discus, mace and lotus are rotated between each of his hands. The 12 Gaurīs are the forms of Śiva’s consort Pārvatī, and they emphasize the memorial character of the stepwell (cf. allied article).

One of the terraces on the front face of the fourth pavilion, facing the reservoir, has six interesting sculptures. They are: Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva, the three Great Gods, with their consorts, on one side of the pavilion, and the three gods of good fortune, Gaṇeśa, Kubera and Lakṣmī, on the other (Fig. 13). Here, Ganesha and Kubera too have been depicted with their consorts. The niches in the lowest level of the walls remained vacant in view of the construction of the bracing or retaining structure built to stabilize the high walls, as mentioned before.

Fig. 13: Ganesha with his consort

However, the logic of the iconographic ordering among the 24 forms of Viṣṇu and the Gaurīs on the reservoir’s walls is not clear, with no symmetry being discernible in the grouping of the deities. The reason for this may be that these sculptures were displaced when the walls had collapsed, and were then reset when the monument was conserved.

Apart from these sculptures of Viṣṇu and Gaurī, there are other important sculptures on either side of the reservoir’s walls, such as one where Viṣṇu is depicted with many arms and is riding on Garuḍa (‘Garuḍārūḍha’), and another one where he is depicted with his human, boar and lion heads (‘Vaikuṇṭhamūrti’) facing each other. These sculptures are in central niches on the higher terraces on opposing walls in the north and south.

The well and its sculptures

Provisions for sculptures were made on all the courses of the well, but the arrangement of the terraces is not the same as on the corridor’s walls. Only the second, third and fourth levels have a stepped profile exactly like the corridor, and here niches alternate with pillared panels. The lowest course is a continuous frieze with divine figures. On the well’s inner circumference prominence is given to Parvati’s five-fire penance and to her consort Śiva, which may be suggestive of the monument’s memorial character (allied article). However, a large number of these niches are vacant now.

The central niches on the rear side on the second, third and fourth courses depict Viṣṇu sleeping on the mythical serpent Śeṣa, accompanied by his consorts and other figures (Fig. 14, see also allied article). Depending on the rise or fall in the water level in the well, one or more of the three sculptures would have been visible always—this seems to have been the idea behind placing as many as three images one above the other.

Fig. 14: Viṣṇu sleeping on Śeṣa

On the fifth course of the well, where certain pillars serve as bases for the brackets supporting the Persian wheel that draws water from the well, the terraced arrangement of the wall ends. The wall here does not consist of recessed niches alternating with projecting panels but has a straight profile with a row of 33 sculptures around its circumference, including a central figure of Viṣṇu seated in the meditative posture of samadhi. The 32 other sculptures flanking him on either side are of various divine couples but due to their damaged condition only a few are identifiable. These include the Brahmanical triad of Śiva, Viṣṇu and Brahmā as well as some of the regents of the directions, known as the Aśtadikpāla.

The sixth and seventh courses of the well’s wall, which were exposed to the elements while the rest of the structure remained buried under sand, are badly weathered.

The medieval chronicler Merutuṅga in his Prabandhacintāmaṇi (‘Wishing Stone of Narratives’, 1306 CE.) attributes the building of the Ran-ki-Vav to Queen Udayamati after the death of her husband, King Bhīmadeva, in 1064 CE (Mankodi 1991:234–35). A later marble portrait of the queen inscribed with her name confirms this fact (Mankodi 1991:230).

Bibliography

Banergea, Jitendra Nath. 1956. The Development of Hindu Iconography. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

Burgess, Jas and Henry Cousens. 1903. The Architectural Antiquities of Northern Gujarat, More Especially of the Districts Included in the Baroda State. London.

Dhaky, M.A. 1961. ‘The Chronology of the Solanki Temples of Gujarat’. Journal of the Madhya Pradesh Itihasa Parishad. 3:1–83.

Jain-Neubauer, Jutta. 1981. Stepwells of Gujarat in Art-Historical Perspective. New Delhi.

Joshi, N.P. 1979. Iconography of Balrāma. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

Lobo, Wibke. 1982. The Sun-Temple at Modhera: A Monograph on Architecture and Iconography. Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck.

Mankodi, Kirit. 2012. Rani ki Vav at Patan. New Delhi.

———.1991. The Queen’s Stepwell at Patan. Bombay.

———.2009. ‘To What God Shall We Render Homage in the Temple at Modhera?’, in Prajñādhara: Essays on Asian Art, History, Epigraphy and Culture in Honour of Gouriswar Bhattacharya. eds. Gerd J.R.Mevissen and Arundhati Banerji. Vol. I:177–98.

Meister, Michael W. 1979. 'Juncture and Conjunction: Punning and Temple Architecture', Artibus Asiae, vol. 41:226–28.

———. ed. 1980. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, vol. 2, part 1. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies.

Mevissen, Gerd J.R., and Arundhati Banerji. 2009. Prajñādhara: Essays on Asian Art, History, Epigraphy and Culture in Honour of Gouriswar Bhattacharya.

Rao, T.A. Gopinatha. 1968. Elements of Hindu Iconography. Vol. 1. Part 1. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.

[1] In the official records of the Archaeological Survey of India, the stepwell is named as 'Rani ki Vav', which nomenclature is erroneous (Mankodi 1991:30, fn. 2).

[2] Ever since the Modhera temple was brought on archaeological record in the early 20th century, it has been considered to be one dedicated to the Sun god. It has been argued recently that the temple was meant for a blend of the Sun god and Śiva rather than for the Sun god alone: Mankodi, 2009:177-198.