Rani ki Vav is replete with sculptures that symbolize water and fertility. There are hundreds of sculptures of young celestial women, known as apsarās, surasundarīs or nāyikās; of god Viṣṇu as Nārāyaṇa and personifications of the river goddesses.

Apsarās/Nāyikās

The walls of the corridor and several hundred vertical panels rest on the basal course at fixed intervals, supported by the overlying coping course. Since the monument was commissioned by the mother of a monarch with significant wealth and accompanying prestige, the vertical props too were not left plain but instead were adorned with figures reflecting the stature of the family. The builders chose sculptures with themes related to the fertilising quality of water, such as heavenly apsarās, surasundarīs, young mothers and serpent damsels (nāgakanyās). These alternate with the major deities in the niches of the corridor’s terraces (see overview article, Figs. 3-4 for examples). Although only around 300 such carvings now remain, it can be safely assumed that the original number must have been much larger.

The corners of the walls include sculptures of the regents of the directions (dikpālas) but the majority are those of female figures standing under elaborate creepers. Images of young women, either alone or with their youthful male partners, have been found in Indian art since early times; some of the earliest documented ones are at the Bharhut Stupa (mid-2nd century BCE) in Madhya Pradesh. These sculptures symbolize fertility and in the case of the apsarās (a term derived from ap-sṛ ‘moving in water’) this connection between water and fecundity is even more apparent.[1] The young women are portrayed in a variety of attitudes—bearing objects of worship such as lamps, conch shells, bells, garlands, or fly-whisks; adorning themselves with earrings or anklets; gazing into a mirror; dancing, sporting with balls; reacting to mischievous monkeys, and so on.

Alongside these gentle figures of apsarā or nāyikā are other female figures—anchorites of cults—clad in ornaments of bone and bearing in their hands skull-cups containing fish and weapons made from human femoral bones (khaṭvāṅga, literally, ‘charpoy leg’, from its resemblance to the leg of an Indian bedstead). These images also feature dogs snapping at the heels of the ominously attired women, providing a realistic touch to the scenes. Even more striking are the sculptures of the ‘serpent maidens’ or nāgakanyā. These figures carry cranial cups overflowing with fish and snakes and have cobras coiled around their limbs. Some of the sculptures depict owls perched on an overhanging ledge while others have peacocks, considered as being the natural enemies of snakes. Neither the maidens nor the slithering snakes appear in any way threatened and the maidens playfully gesture in tarjanī hasta as if they are about to strike them. Several elements of this motif—the nudity, owls, peacocks, the tarjanī hasta (as though admonishing the snake) and the skull-cup with fish, with its esoteric tantric symbolism—add to its enigma[2].

The presence of serpent maidens is not surprising in a stepwell, since serpents, like the apsarās, were conceived of as primarily as water-dwelling creatures. and sporting in water. Interestingly, while apsarās, who play an important part in celestial mythology, have always been an essential component of temple statuary, the nāgas, or snake figures, remained rooted to their subterranean dwelling, represented mostly on monuments that were closely connected with water.

Out of the several hundred such panels, only a few can be described and illustrated here.

Fig. 1: Apsarā

Fig. 1 is of an apsarā or nāyikā biting an aromatic twig, with perhaps a betel leaf in her left hand. A bearded dwarf tickles her foot.

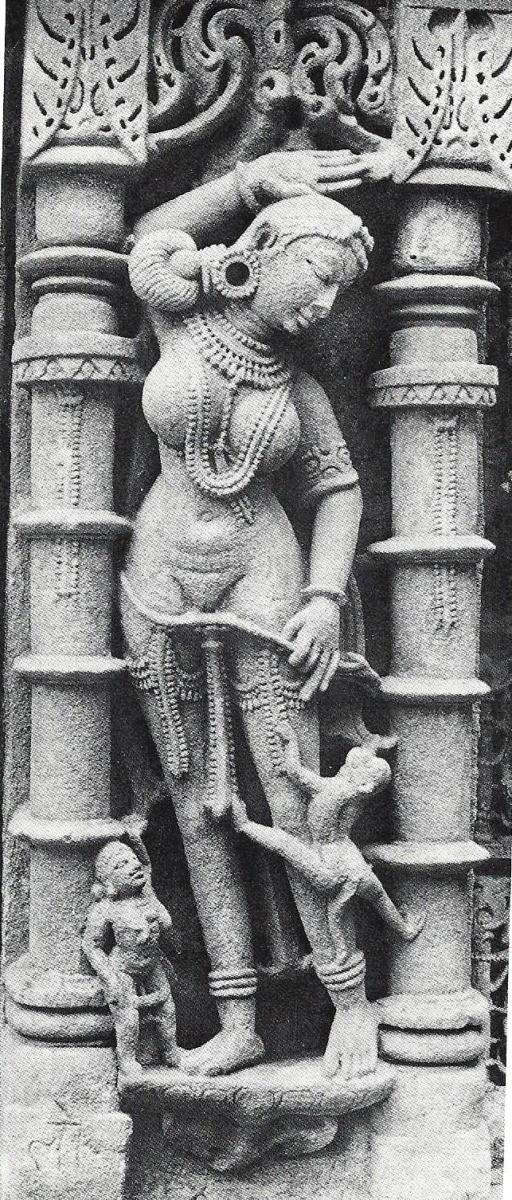

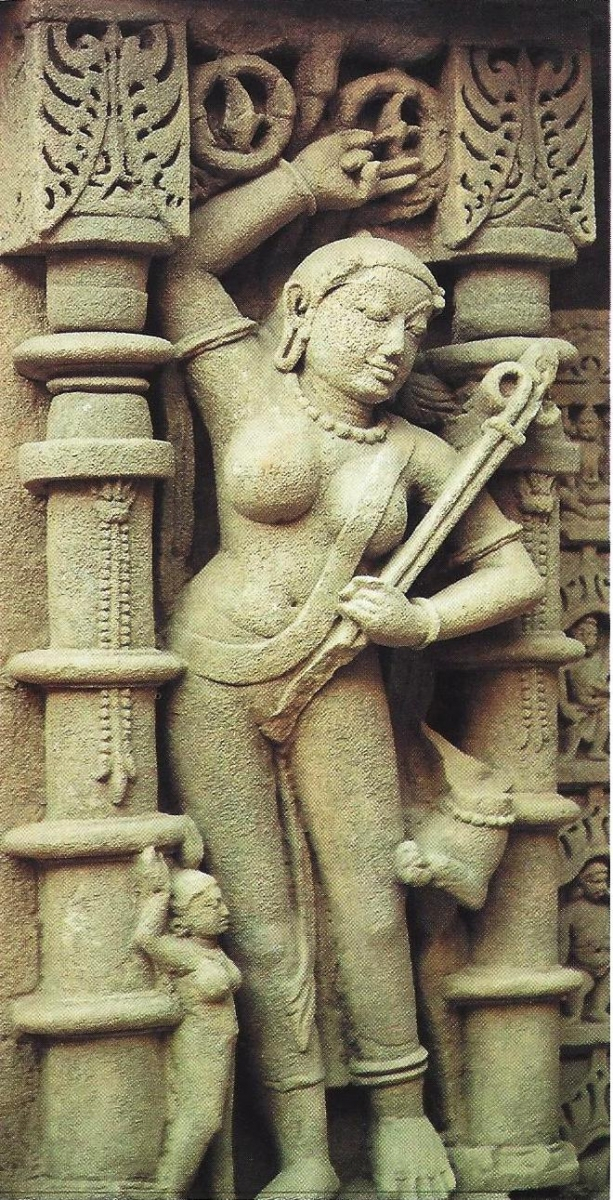

Fig. 2: Dancing female medicant

Fig. 2 is of a dancing female ascetic, probably a Yoginī. That she represents a left-handed (tantric?) sect is evident from the skull-cup with a fish, and the khaṭvāṅga in her hands. Her hair is in a jaṭā; she is adorned with ornaments, animal skin is wrapped around her waist, and she wears sandals on her feet. A bearded ascetic beats a drum.

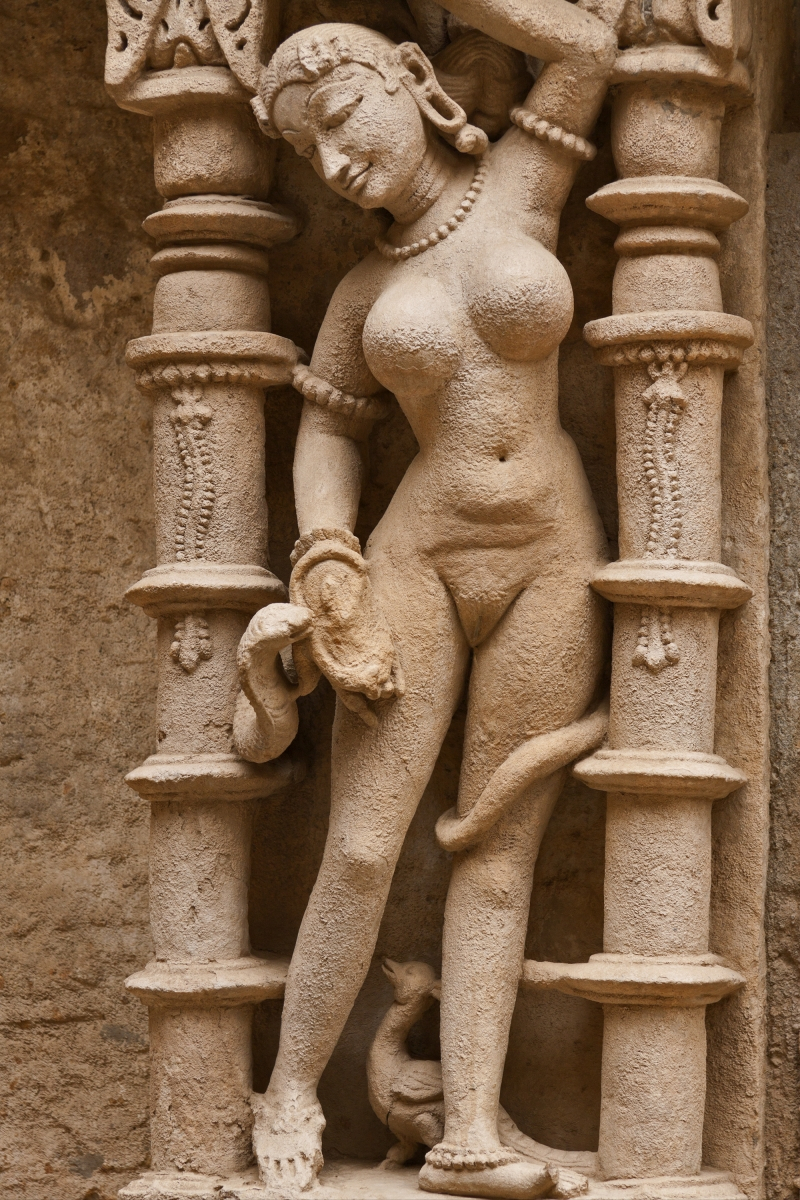

Fig. 3: A nāgakanyā in the corridor

Fig. 3 represents a nāgakanyā, depicted in daring nudity. A skull-cup with a fish is in her hand, and a snake crawls up her legs as if to sip from it; the fingers of her raised left hand form the tarjanī gesture of admonition; a peacock is at her feet; and three owls are perched on a ledge at the top. The same motif is represented in the interior of the well.

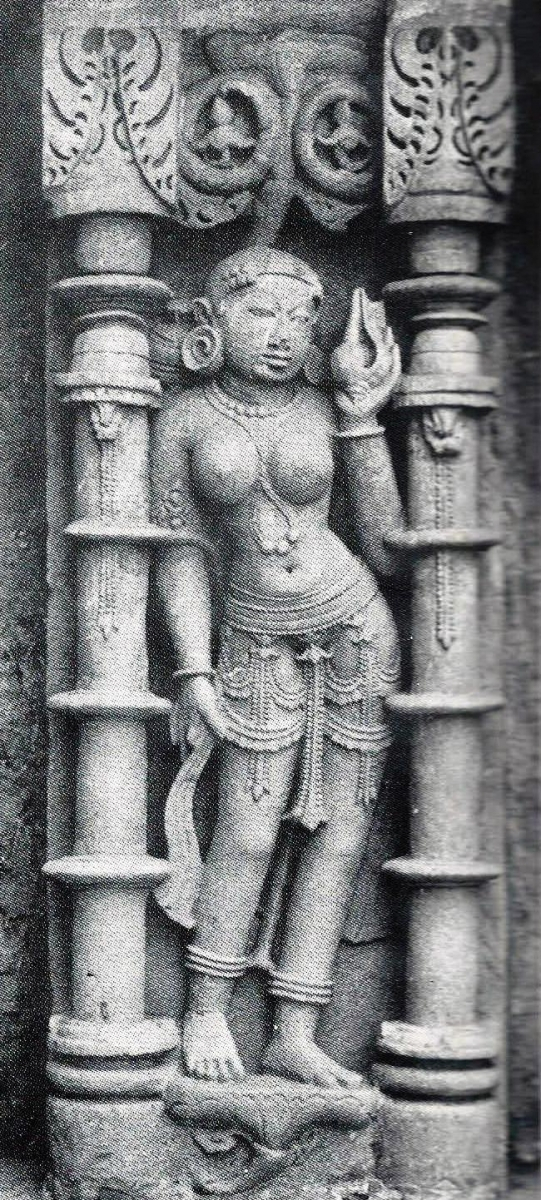

Fig. 4: A nāgakanyā in the well

Fig. 4 on the inside of the well has an identical theme but the feeling for sculptural form is different in the two.

Fig. 5: The nāyikā 'Karpūramañjarī' (camphor spray), in the reservoir area

In Fig. 5 the nāyikā, Karpūramañjarī, is drying her hair after her bath; a goose, mistaking the water-drops for pearls, swallows them up. This sculpture is at the edge of the basin or kuṇḍa fronting the well, as though the heroine has just taken a bath there![3]

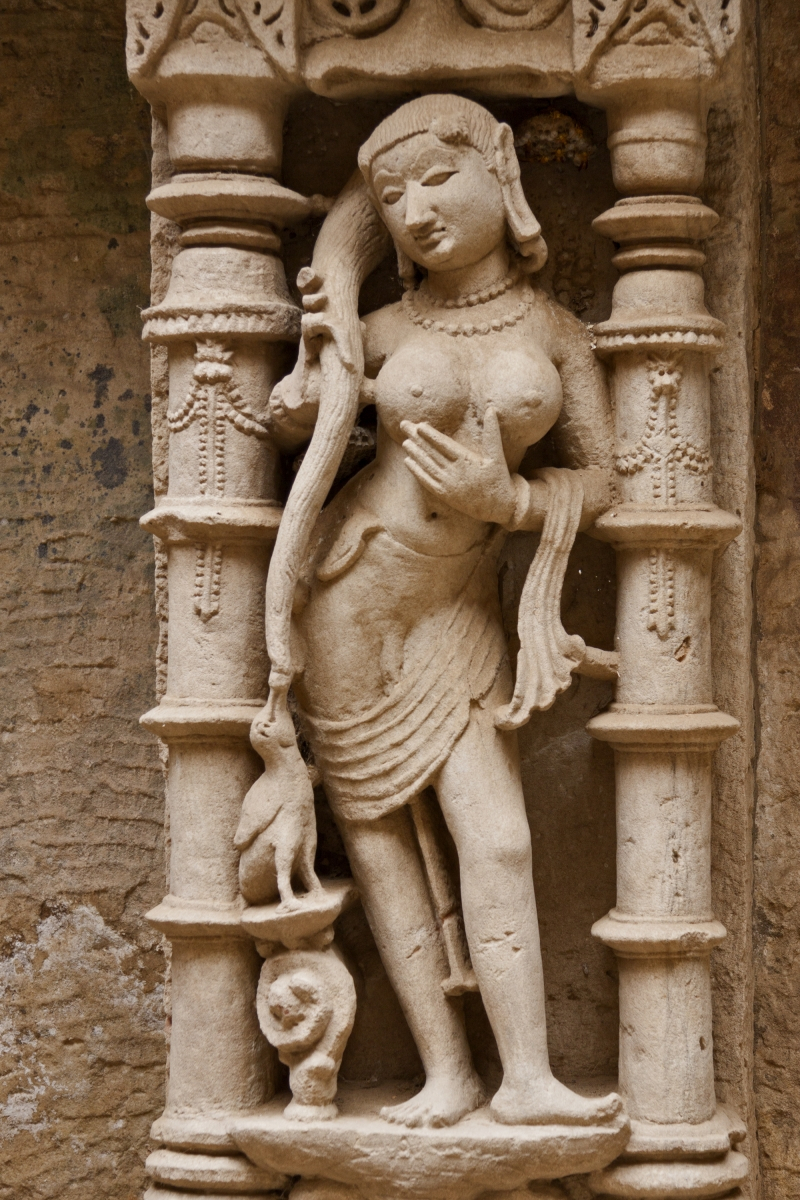

Fig. 6: Apsarā or Nāyikā with a bird

Fig. 6 is of a nāyikā with a bird in one hand and a bunch of mangoes in the other. She gestures as though tempting the bird with the fruit. Literary motifs must have contributed to artistic tradition. The motif of birds with young women is reminiscent of the young bride’s embarrassment in front of her elders: the bird having heard the loving exchanges between the newly married couples during the night innocently repeats everything before the elders—the bride offers it pearls from her necklace pretending they are pomegranate seeds.

Fig. 7: Young women being teased by a monkey

Fig. 7 is of an apsarā being teased by a monkey. The animal is tightly clinging to her leg and as she tries to shake it off her garment slips from her waist. At her feet is a smaller female figure, with a snake coiled around her breasts.

Fig. 8: Apsarā adjusting her ear ornament

Fig. 8 is of an apsarā adjusting her ear ornament by looking into a mirror; a smaller female figure near her feet is carrying a bowl of cosmetics on her head.

Fig. 9: Apsarā with objects of worship

In Fig. 9, an apsarā holds a cloth and a large sinistral conch. Her necklace is made of a plain string with three large beads—the same kind of ornamentation is often seen at this monument. It is worth noting that all the conch shells depicted here are of the sinistral shell type which was considered more sacred than the common dextral one.

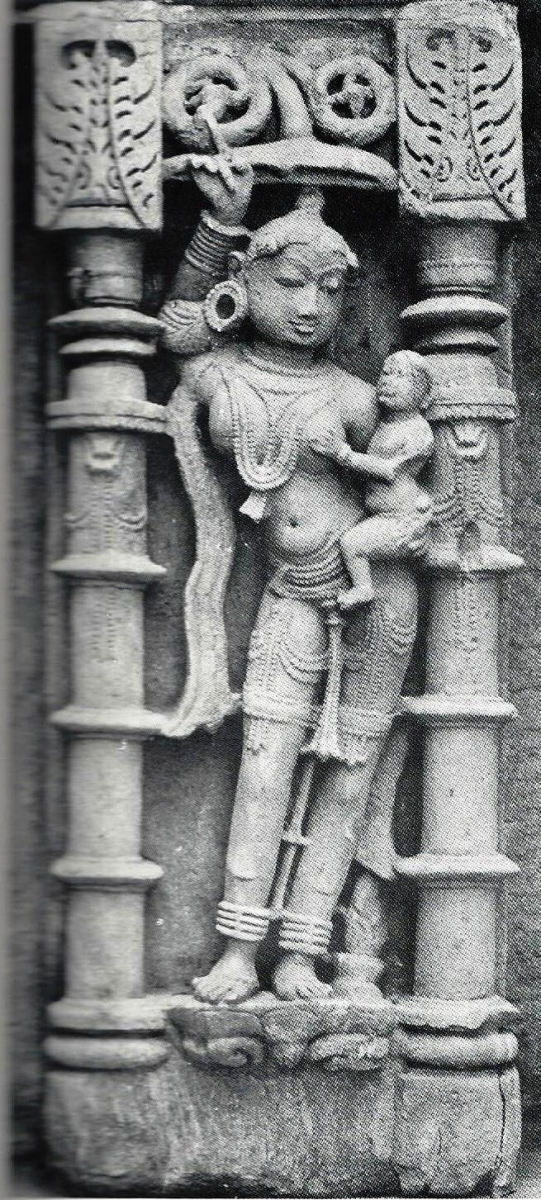

Fig. 10: A young mother points out the moon to her child

Fig. 10 is of a young mother (putravallabhā nāyikā) pointing to the moon, with her child on her hip.

Fig. 11: A Nāgakanyā

Fig. 11 is of a nāgakanyā, clad in nothing but a coarse sash across her shoulder. She has a skull-cup in her right hand, into which she dips her left hand. A snake has knotted itself around her knees. Her sash closely resembles the one worn by the Buddha in the Avatāra series of the monument (see overview article, Fig. 9).

Fig. 12: Apsarā at play

Fig. 12 is of an apsarā playing with balls. She wears a supporting band across her chest.

Fig. 13: Female mendicant

Fig. 13 is of a Yoginī. She bears in her upraised hand a skull-cup with a fish; in her left hand she holds a long noose. The fish in the skull-cup and the noose in her hand seem to be related in some esoteric manner, since they occur together, but the connection is no longer clear. Unlike in other representations of this motif on this monument, here her hair is not matted to form a jaṭā, but is styled in the normal way.

Fig. 14: A nāgakanyā playing with a snake

In Fig. 14, a nāgakanyā playfully strikes a snake which has slithered up her leg. The snake’s head is disfigured. The maiden’s left hand forms what may be called the tarjanī gesture, but at the same time, the tips of the extended fingers support a small object—which could be the snake’s crest jewel snatched away in jest.

Fig. 15: Female mendicant or Yoginī

Fig. 15 is of a Yoginī. She is clad in a simple garment which reaches down to her ankles, and a sash or scarf draped over her shoulder. She wears a necklace with large beads which could be made of bone. In her left hand, she carries a metallic noose or pincers, with straight sides and a clasp securing its loops. At her side, a big dog is seen to be attacking her, while she wards him off with her free hand forming the tarjanī gesture. The presence of the barking dog was no doubt inspired by daily life in medieval India.

Fig. 16: Apsarā putting on an anklet

In Fig. 16, an apsarā is shown to be putting on an anklet.

Fig. 17: Apsarā or nāyikā being harassed by a monkey

Fig. 17 shows an apsarā or nāyikā being harassed by a monkey that clings to her thighs, causing her lower garment to slip away from her waist.

Fig. 18: Apsarā forming the tarjanīmudrā and pointing downwards

Fig. 18 is of an apsarā forming the tarjanīmudrā and pointing downwards.

Fig. 19: A Nāgakanyā playing with a snake

Fig. 19 is of a nāgakanyā playing with a snake.

God Viṣṇu as Nārāyaṇa

Viṣṇu in his Nārāyaṇa aspect is intimately associated with the cosmic waters in mythology. Wells, tanks, and stepped wells were consecrated to him. The images of Viṣṇu reclining on Śeṣa, the mythical serpent that appear at these sites serve as symbols reminding the visitor that the well’s water is that archetypal substance in which Viṣṇu himself reposed at the beginning of creation. At Rani-ki-Vav too, the Śeṣaśayana form of Viṣṇu-Nārāyaṇa was introduced at many prime locations such as the three central niches of the well, one above the other, as well as on the corridor’s walls (see overview article, Fig. 14)

River goddesses

Fig. 20: Frieze depicting the river goddesses

The basal frieze on the corridor’s walls is elaborately carved. Rows upon rows of female deities, identical in all respects, are seated in the varada or blessing pose with a pitcher of sacred water and a pair of lotus flowers in their hands (Fig. 20). The lotus and pitcher are clearly evocative of water and these figures, then, may be representative of the rivers of the country, personified and replicated a thousand times, as if to augment the sanctity of the well’s water. The spirits of the rivers were invoked through mantras (sacred chants) and rituals at the time of the consecration of any reservoir or well. The two rivers that are considered the most sacred—Gaṅgā and Yamunā—mark the entrance to many shrines. Even today, devout Hindus invoke the seven most sacred rivers, Gaṅgā, Yamunā, Godāvarī, Sarasvatī, Narmadā, Sindhu and Kāverī to be present in their bath water (Nadīstotra). The vast resources of the royal patroness of the stepwell made it possible for the sculptors to depict such a rich variety of mythological figures, lending to the Rani-ki-Vav an air of sanctity.

References

Mankodi, Kirit. 1991. The Queen’s Stepwell at Patan. Bombay.

———. 2010. Reviews of Steps to Water, Water Architecture in South Asia and Therapeutics in Indian Sculptures, Marg 61.4:86–89. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

———. 2012. Rani ki Vav at Patan. New Delhi.

Rao, Rekha. 2006. Therapeutics in Indian Sculptures: Ranki Vav. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

[1] Recently one author (Rao 2006) has seen in these youthful figures not apsarās and their association with the fertilizing power of water but rather women afflicted with various diseases and disorders: thyroid, rheumatism, respiratory diseases and indigestion. See this author’s review in Mankodi 2010.

[2] These stunning personages occurring on many Indian monuments are usually passed over by scholars without comment. For examples, see Mankodi (1991:174, fn 70).

[3] ‘Karpūramañjarī’ is the young heroine of a play of the same name by the poet Rājaśekhara, written in the 10th century CE. When a magician casts a spell, Karpūramañjarī, then bathing, is transported in the same state—clothes sticking to her skin, wet hair—into the presence of the king, and the two fall in love straightaway. The motif of an apsarā drying her hair after a bath, with a goose (who, in folklore, eats only pearls) swallowing the water dripping from her hair, was much favoured by Indian sculptors. In visual arts, a figure depicted in this manner is identified as the nāyikā Karpūramañjarī. A panel with various types of apsarās carved on the Vijay Sthambha (Victory Column) of Rana Kumbha (r. 1433–68 CE) on the Chittorgarh hill in the 15th century has the same motif with the inscription, ‘Karpūramañjarī.’