Banner image: 'Bhishma Version 2'; Copper and brass welded; Height 210 cm; Collection of Nina Kothari, Chennai

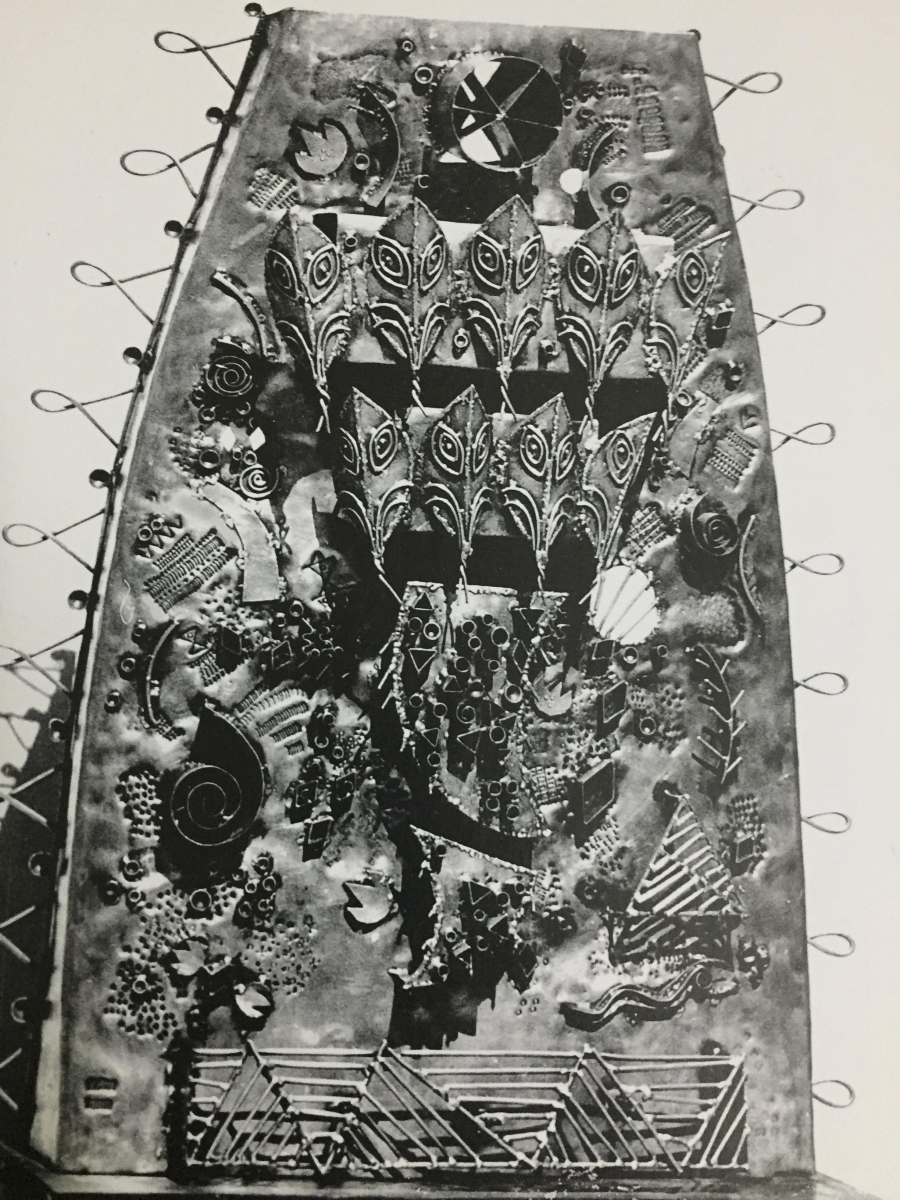

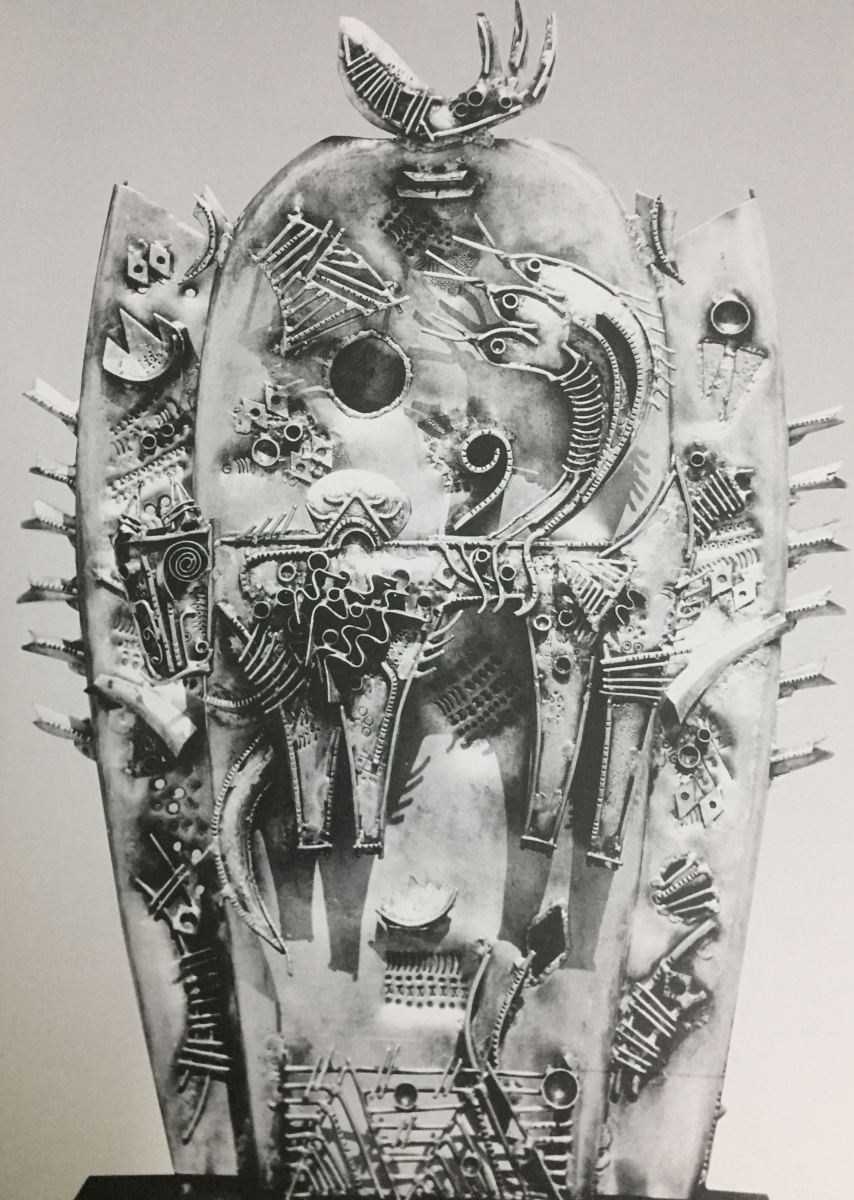

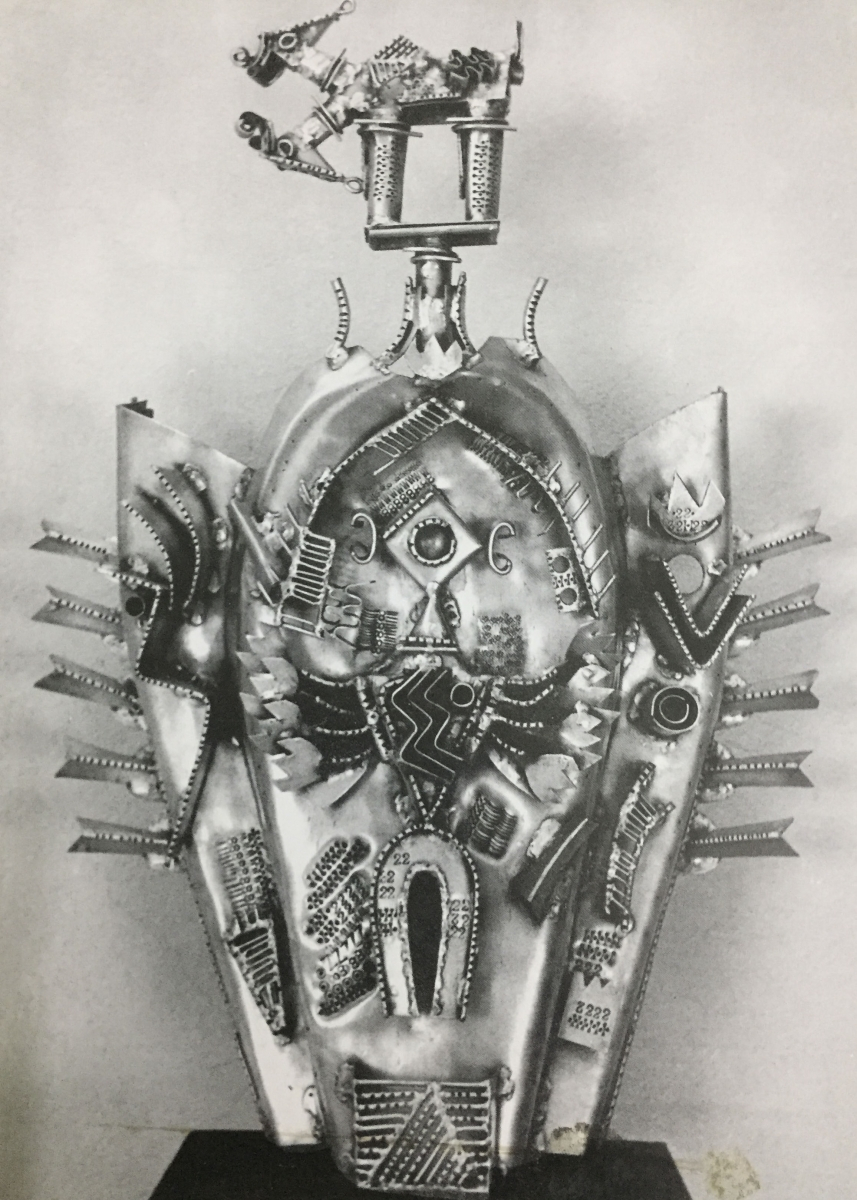

Phyllis Granoff, a Harvard Indic religious studies professor and an art critic, identified early in Nandagopal's sculptures a dialogue with India's ancient religious imagination by an artist with contemporary and modern sensibilities. Writing in the journal, Art International in 1980, Granoff found structural similarities between the South Indian temple gateway tower, the gopuram, and the early sculptures of Nandagopal. Granoff observes that the South Indian gateway tower involves two visual processes: one, seen from a distance, the gopuram offers a broad base narrowing and pointing towards the sky; the other, observed in proximity, it provides narrative panels and figurines frozen in activities, mythical or real. Comparing the gopuram's visual processes with that of the early sculptures of Nandagopal, Granoff equips us with the key to enter into the magical world of Nandagopal (Granoff 1980). In a 1993 article on Nandagopal’s works included in the volume, Contemporary Indian Sculpture: The Madras Metaphor, Ranvir Shah confirms with the artist that the gopurams were indeed his inspiration for his early sculptural ideas (Shah 1993:154). While the two sculptures, 'A Many Headed Figure' and 'A Naga Symbol', both crafted in silver-plated copper in 1968, stand testimony to Granoff's theory likening them to that of the gopuram's structure, what intrigues us are the details on the surface. Both the sculptures evoke primeval sensibilities in their compositions, but they indicate no specific meanings. The stack of protruding triangular faces, a wheel on top, an inverted triangle for a body with wavy lines and pedestal with short legs give the 'Many Headed Figure' a known evocation and presence, but its meaning remains elusive. Comparatively, 'A Naga Symbol' appears to be more accessible with its stack of sharply edged metal leaves constituting an inverted triangle of a face, but this sculpture too defers its meaning. These two sculptures (Fig. 2) share a few visual elements such as the wheel on top, randomly placed cyclonic twists and triangle grids, twisted loops on the sides and a lattice mesh for the base. Indeed these two sculptures daunt us like totemic structures in their commanding presence, but they also charm us with their enigmatic quality.

Fig. 2 (i). 'A Many Headed Figure' (1968); Silver plated Copper Height 120 cm; (ii): 'A Naga Symbol' (1968); Silver-plated copper; Height 120cm

In a conversation with art critic Joseph James, Nanadgopal specifically explained his outlook towards religion, ritual, mythology and tribal lore. Joseph James poignantly asks, 'Has your "non-figurative, non-abstraction", if I may so describe your work, anything to do with religion? A good many of your sculptures are on religious subjects, and almost all of them have strong iconic aspect.' Nandagopal replies, 'When I look at a sculpture, I do not see it as religious or secular, nor am I aware of the distinction as I plan my own sculpture. What is true to life, as I see it, is something, which is both one and the other at the same time. I have sensed this from the start in the lives of people around me, which I share with them, in the nature of belief, behaviour, art, and outlook. My sculpture cannot be true to life, I feel, if this unknown "something" is not its subject or its ground. I do draw heavily from legend, mythology, and ritual because I find in them rich figures for the "unknown something" which I feel reflected all around. I have not known it as an image or abstraction' (James 2008:33).

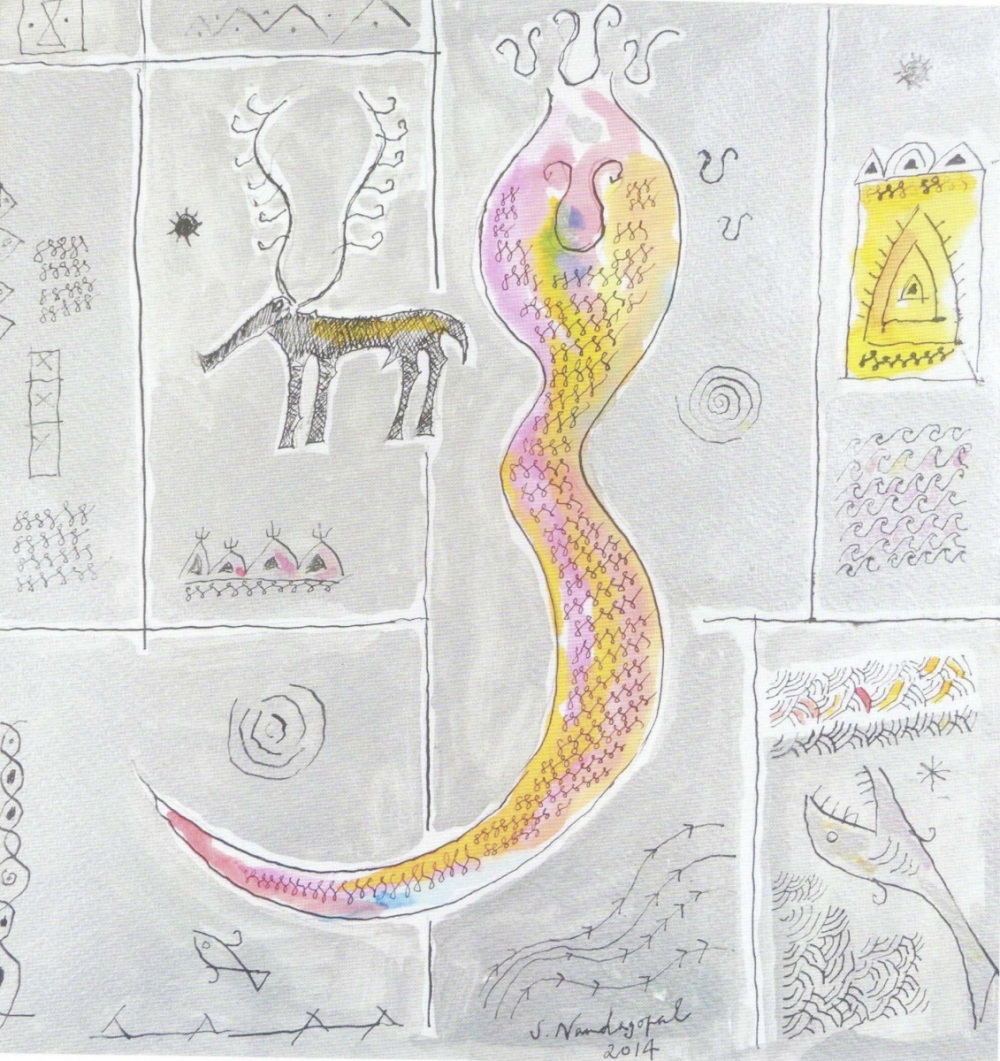

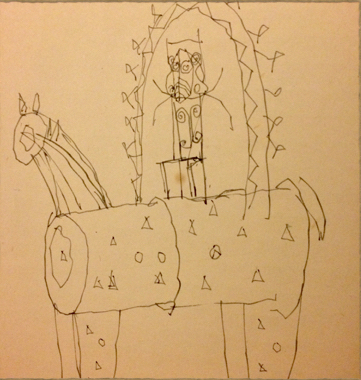

Phyllis Granoff, perceptive she is, attributes that Nandagopal’s fascination with the 'unknown something' must have come from his father, the legendary painter K.C.S.Paniker, as a formative influence. Writing about the surface details of Nandagopal's early sculptures Granoff informs us, 'these details recall the decorative surface ornamentation of folk art, .... They also recall to mind the enigmatic notations on some of the works of Madras painters of the 1960's, most notably K.C.S.Paniker, Nandagopal's father. K.C.S.Paniker radically altered his style of painting in the 1960's inspired by Paul Klee, by mathematical manuscripts, and by the revival of Tantric symbols and Tantric philosophy. He produced a remarkable series of paintings called "Words and Symbols" in which a number the elements found in Nandagopal's sculptural decoration occur. Nandagopal has here removed them from the metaphysical context in which his father had ordered them, and in search of his own process of ordering' (Granoff 1980). While it is not true that Nandagopal entirely removed the metaphysical contexts of decorative ornamentations because he produced an exhibition of coloured ink drawings on paper titled, 'The Metaphysical Edge' in 2014 (Fig. 3), he did order the surface details of his sculptures to suit his sensibilities and worldview.

Fig. 3. From the watercolour and coloured ink on paper drawing series, 'The Metaphysical Edge' (2014)

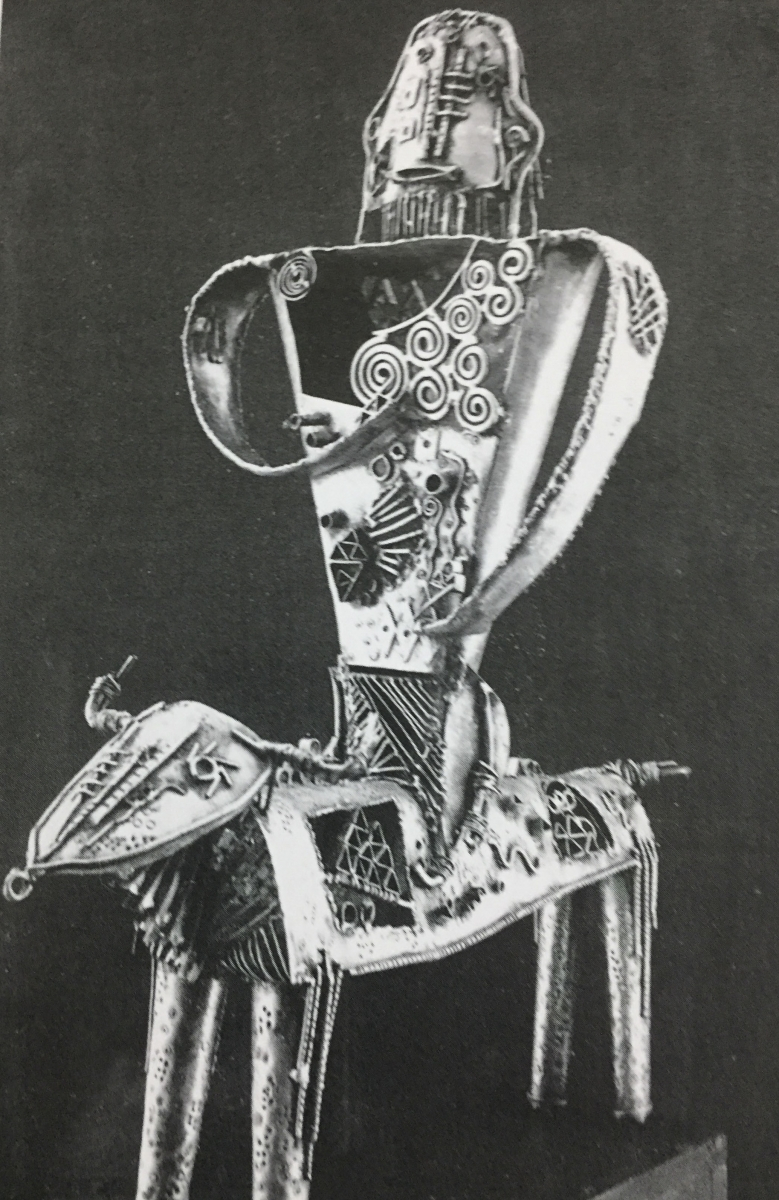

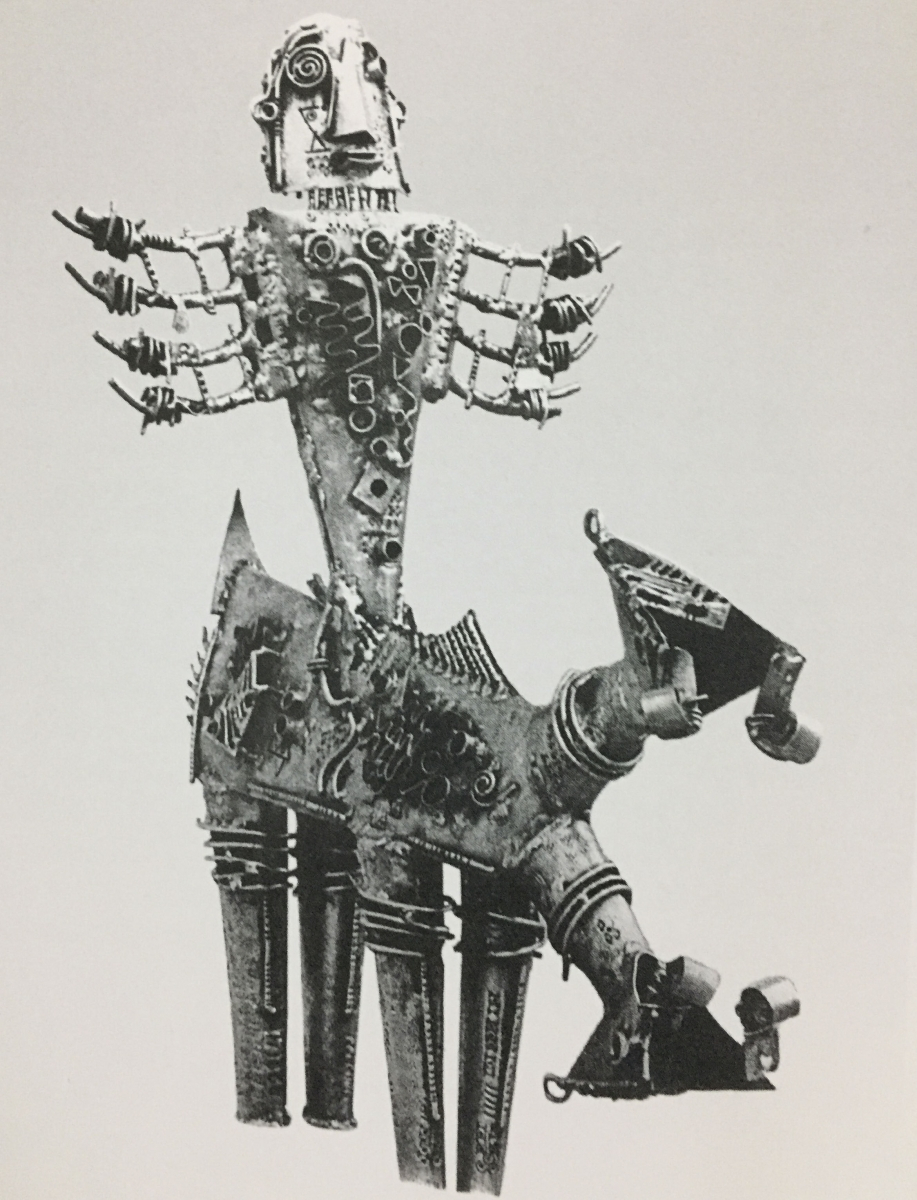

If we look closely at the animal figurines and the rider sculptures of Nandagopal in the late 1960s, we are struck by their referential resemblance to the dhokra metal crafts of the tribes of Central India. The rider on a horse or any animal is a central figure of worship and ritual across India, ranging from village Ayyanar figures in Tamilnadu to votive tribal rites in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. A silver-plated copper sculpture of a rider in 1969 and a bull sculpture of the same material reveal Nandagopal’s early attempts to place his art in prominent relation to the widespread Indian tradition of riders and the ethos of folk and tribal art. We see his efforts to retain the references to tribal and folk art even later when he worked on classical Puranic themes such as Garuda, Vishnu and the Mahabharata episode of Bhishma resting on a bed of arrows. If tribal folk aesthetics of metal crafts thrive in the simplicity of their forms and expressive mental modes, we see Nandagopal enhancing their mythology by presenting them as artefacts. Nandagopal's rider series and the animal sculptures are not representational, but they are remnants and relics of a civilisation. An early Nandagopal's drawing for the rider sculpture series indicates how he brings about the effects of an artefact into his sculptures. After reducing the body of the animal into a bare minimum of a drum and the neck into a pipe, Nandagopal embellishes his drawing of the rider and his animal with dots, triangles and an arch (Fig. 4). We see that those decorative elements of the picture translate onto the sculptures as natural corrosion of the metal and the designs of the artefact. In 'Bull' we see a bird etched on the metal body and a calf cuddling beneath. The corroded metal shapes intermingle with triangles and holes revealing the Bull to be a metal sheet crafted, welded, and beaten into a form.

Fig. 4 (i). 'Rider' Silver-plated copper (1969); Height 80 cm; (ii): 'Bull' Silver-plated copper (1969); Height 50 cm; (iii): An early drawing of bull

Fig. 5 (i). 'Rider' (1971); Silver-plated copper; Height 20 cm; (ii): 'Rider' (1971); Silver-plated copper; 80 cm

In the rider series of sculptures (Fig. 5), we see Nandagopal presenting numerous possibilities of sheet metal craft in the tiny little embellishments with which he adorns his figurines. Twisted wires, lattice meshes, spikes, wavy lines, circles, bolts, crescents, and triangular shapes adorn the body of the rider and the animal. While it is possible to read the assemblage of Nandagopal's visual language of metallic elements on the forward-thrusting, multi- handed heroic figures with magnificent postures as the portrayal of divine power, we are also reminded of what artefacts they are. If the twin-headed animal of the silver plated copper rider (1971) tells us how mythical these sculptures are, they also invite us to view them as well-constructed artefacts. The triangular bodies of the riders balance well with the upward thrusting hands and their frozen majesty. One would venture to say that Nandagopal is assembling his evolving visual language not to embellish or decorate but to create self-referential artefacts.

Fig. 6 (i). 'Shattered Image' (1975); Silver-plated copper; Height 120 cm; (ii): 'Ritual Memory' (1976); Silver-plated copper; Height 76 cm

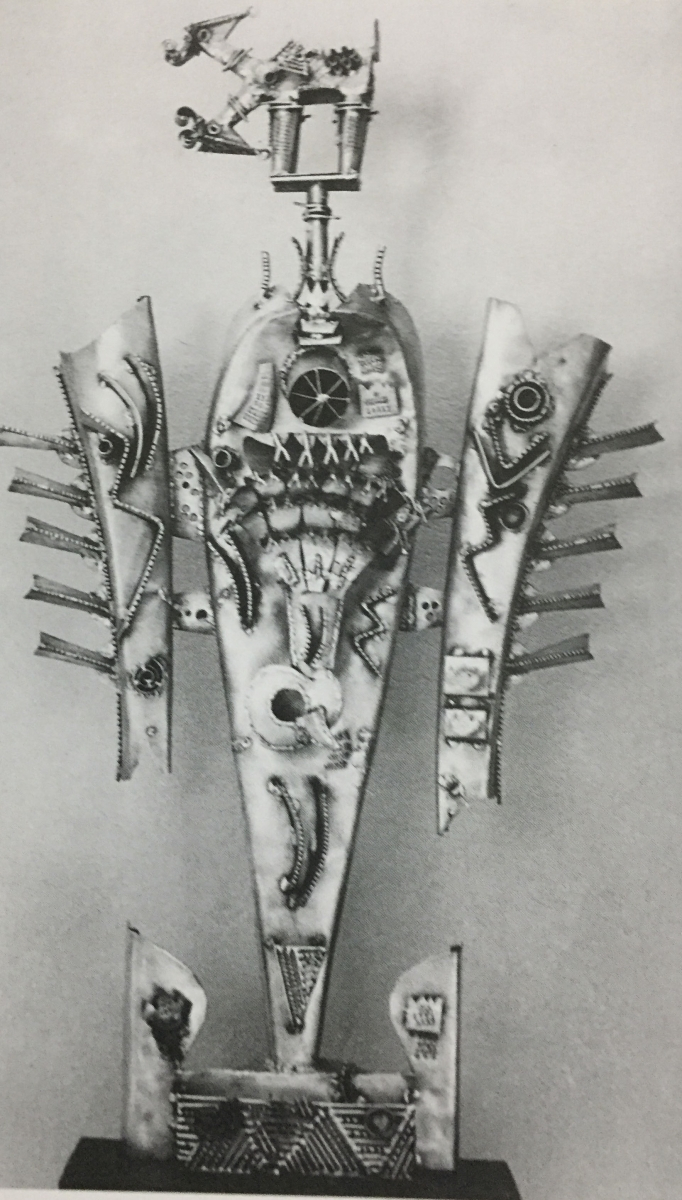

We see that Nandagopal advances the self-referential qualities of his sculptures in works such as 'Shattered Image' (1975), 'Ritual Memory' (1976) (Fig. 6) and 'Deity and Double-Headed Animal' (1976). Without referring to any particular tradition or mythology, these sculptures launch Nandagopal as a new mythmaker presenting the modernist delirium of the soul in his sculptures. Stylistically these sculptures share several features with other sculptures of the 1970s like 'Tortoise as Deity' (1978) and 'Mesha' (1979) (Fig. 7). Referring to the pictorial quality of his sculptures of the period Nandagopal said in an interview, 'The drawing that developed in Madras removed the reference to sculpture altogether. I am talking of the drawing developed by K.C.S.Paniker, Reddeppa Naidu, Santhanaraj, Ramanujam and others. They evolved a drawing with which one could make pictures straightaway without the mediation of sculptural forms. I had followed the work of these painters very closely; I was actually brought up on that drawing. When I started to sculpt it took me some time to discover that my sculpture was something that arose from the drawing. What I am saying is that in my work the relation between sculpture and drawing stood reversed. My sculpture turned directly pictorial like the drawing, which brought it into being, and stood free of any "sculpturesque-ness''' (James 2008:35).

Fig. 7 (i). 'Tortoise As Deity' (1978); Silver-plated copper; Height 75 cm; (ii): 'Mesha' (1979); Silver-plated copper; Height 120 cm

Viewing Nandagopal’s sculptures of the '70s in the context of the modernist aesthetics of Madras Art Movement and its allegiance to the nativist lyricism and calligraphy of the drawn line is illuminating. We notice that the 'Shattered Image' and the 'Ritual Memory' are asymmetrical in the arrangement of their surface details. Scattered and distorted, the graphic elements exhibit a different harmony and entirely new order compared to the Animal and Rider series. We see that these sculptures are completely liberated from their referential moorings of folk and tribal lore but they establish a new syntax for Nandagopal's visual language. During this period Nandagopal came to assert the frontal pictorial sculpture as his medium of artistic expression. Acknowledging his indebtedness to sculptor P.V.Janakiram for reinventing the frontal sculpture as a modern medium, Nandagopal once explained, 'It is not necessary to imitate in sculpture the three dimensionality we sense in our experience of the ordinary world. One can bring it all to the surface and lay it flat in a spread. This is frontality. And it is a technique. There is nothing religious about it. No iconic value. It does not ask the viewer to go round it or box it in. It is perforated sheet metal sometimes with light from behind, with nothing at all at the back of it, nothing at all' (Shah 1993:159). Having taken away the religiosity and the three dimensionality the animistic deities of Nandagopal's sculptures become parables of modern man in metal sheets presenting the hallucinating details on the surface and exposing the hollowness inside. Reacting to his works Mulk Raj Anand wrote, 'The total effect is to create a restlessness beyond the supine images before which the orthodox burn incense. Beneath the outer form one can see the shadows of delirium of the human soul.'

The frontal sculpture technique assisted him well to picture complex mythological and philosophical concepts. The Matsya Purana conceptualises the universe as a milky ocean with two oceanic currents, one visible and another invisible and subterranean. Between these two oceans, Vishnu sleeps as Maya, the illusory reality perceptible to the human senses. Nandagopal in his 'Koorma Tortoise as Deity' (1978) sculpture captured the subterranean cosmic figure of creation and reality passing through time in the great epochal sequence. 'Tortoise as Deity' demands us to look at the sculpture from the below. It is more orderly than the 'Shattered Image', but we see Nandagopal's familiar motifs of meshes, snakes, springs, and animal figures mysteriously leading to the fish on top, the visible world.

Fig. 8 (i). 'Deity and Double Headed Animal' (1976); Silver-plated copper; 60 cm; (ii) and (iii): Details

'Deity and Double-headed animal' (1976) (Fig. 8), 'Tortoise as Deity' (1978) and 'Mesha' (1979) show Nandagopal refining his art of the frontal sculptures and moving away from the visual processes of the gopuram. 'Deity and Double-Headed Animal', a silver-plated copper sculpture of 1976 reveals to us that Nandagopal had refined his visual elements to configure recognisable shapes yet retained their mysterious qualities. We see a central figure with multiple lotus hands, a horse shoe for legs, two supporting columns of bows, arrows and weapons. The square head of the figure is like an embedded jewel, and on the arch top of its head, there is a two-headed animal balancing on a tip. More than the surface details, the sculpture draws our attention to its axis, balance, optical depth and the powerful affect of a jewel—the characteristics that became the defining features of his later works. In 'Mesha' (1979) we see these traits of a big sculpture balancing on a thin bottom, another signature mark of Nandagopal's later works.

The transition to space shifting narrative sculptures was the result of Nandagopal's experiments with the surface, depth, axis, and line. About the sculpture 'Ritual Image' (1978), Nandagopal said in an interview, 'I wanted to see the changes I could try with the fulcrum and see how much weight could be taken at one end. I also wanted to see how far I could stretch the axis. Earlier my pieces had one shape and also no movement. With this piece, a lot of symmetry came in. The piece has a tail that rises in the sky as if tracing the line a blazing comet.' The movements Nandagopal brought into his later works such as 'Memory of a Hero Stone' (1985) and 'Garuda' (1986) are akin to the space-shifting metamorphoses in the narratives of avatars of Vishnu and world mythology in general. Shape-shifters are part of many cultures. In Nordic mythology, Odin could manifest himself as any beast or bird; and in Greek myth, Zeus assumed animal guises such as that of a bull and a swan to pursue beautiful young women. In Buddhist thinking, however, there is no constant, underlying being; each form, even the perfected form, is only an appearance. For Nandagopal, the presentation of space shifters in vertical narrative sculptures is not only an experimentation in sculptural ideas, but it is also a civilizational statement and an aesthetic value.

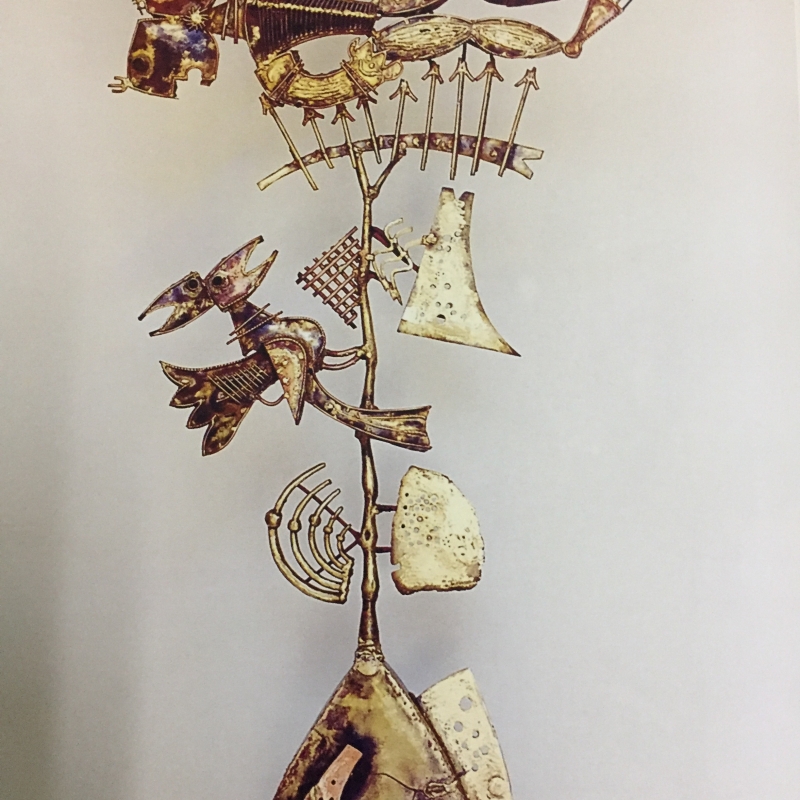

Fig. 9. 'Memories of a Hero Stone' (1983); Copper and Brass welded; 120 cm

Variously referred to as 'drawings-in-space', 'flight of forms', and 'animations-suspended-in-air' by different critics, the space-shifting sculptures of the '80s exhibit Nandagopal's excellent workmanship and rare refinements (Doctor 2007). In the '80s, while the 'unknown some things' of his formative years have transformed into lyrical compositions of movements and enactments, his subterranean visual language finds articulations in expressing collective memories. In Nandagopal's sculptures, we do not find expressions of personal memories. Susan Sontag once wrote, 'What is called collective memory is not remembering but a stipulating; that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.' This is particularly the case of Nandagopal's series on 'Memories of Hero Stone'. Nandagopal did the series on hero stones apparently from the mid-1980s to 2006. The hero stone tradition again is a prominently Tamil folk tradition of several centuries with parallels all over the world, and by placing his sculptures in evocation and projection of this heritage, Nandagopal stipulated the sacredness of remembering valour, sacrifice, renunciation, love and a pastoral life of living in unison with birds, animals, rivers, animals and gods.

In his space-shifting sculptures of mythological imagination, Nandagopal's arrangement of memories of hero stones fused animals, birds, and humans in the form of a tree with a small bark and multiple wild branches. As we see in the copper and brass welded sculpture of 1983 (Fig. 9), the very first one in the series, there are three layers of vertical spaces. Grounded on the earth is an animal's body with a bird for a tail, an elephant for a face, and two jars for a body: one jar houses a warrior and another is the body of bird whose beak forms the second layer of the sculpture. On the beak of the bird, the third layer is fused with dancing figures and a mesh of arrows. The fusion of bird, animal and human is like a blurring memory on one level, and it is a provocative presence of a union with nature on another level. As much as he subjected the fusion of elements to his mythological imagination, Nandagopal transformed all representational forms into impressions fused in a moment, as we see in his sculpture, 'Bird' (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. 'Bird'; Silver-plated copper; 75 cm

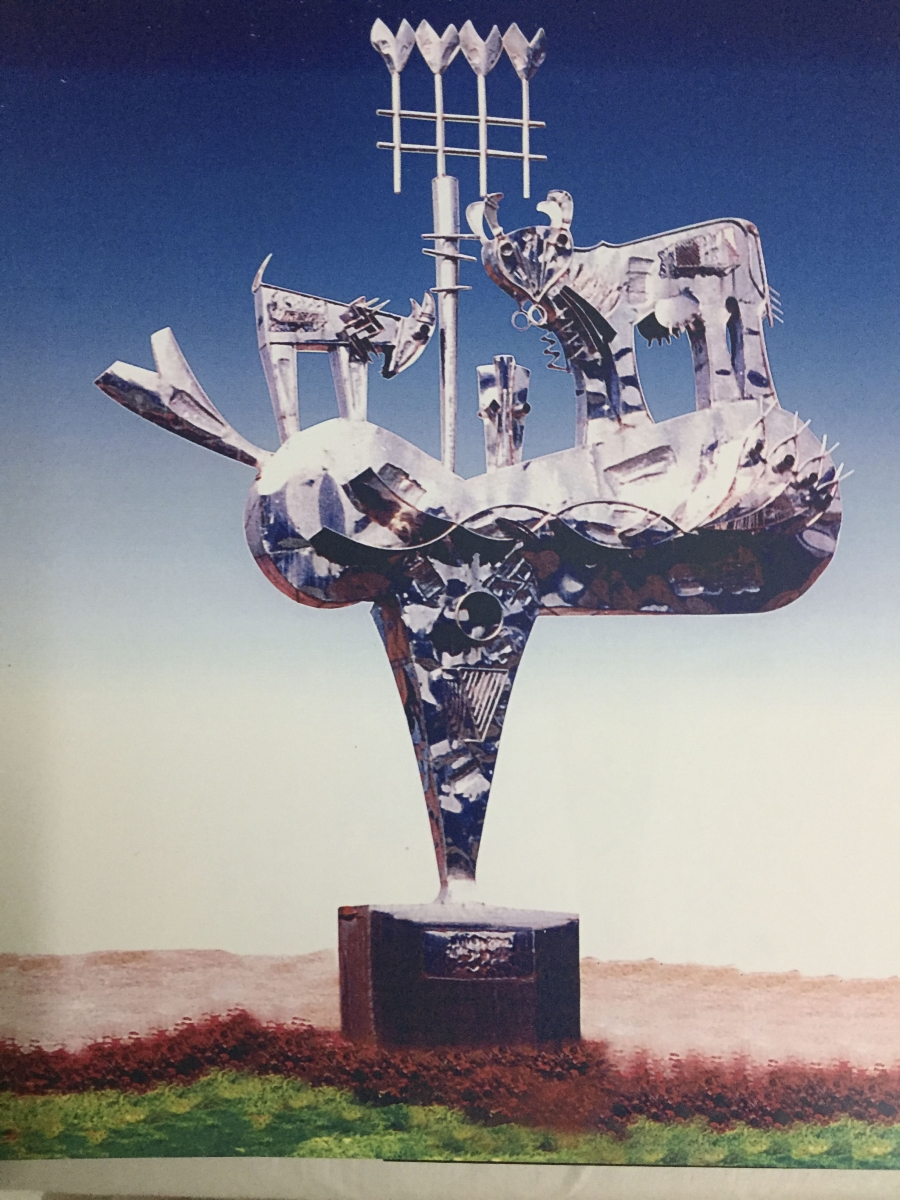

Fig. 11. 'Tree'; Stainless steel; Height 600 cm (model made in 1981)

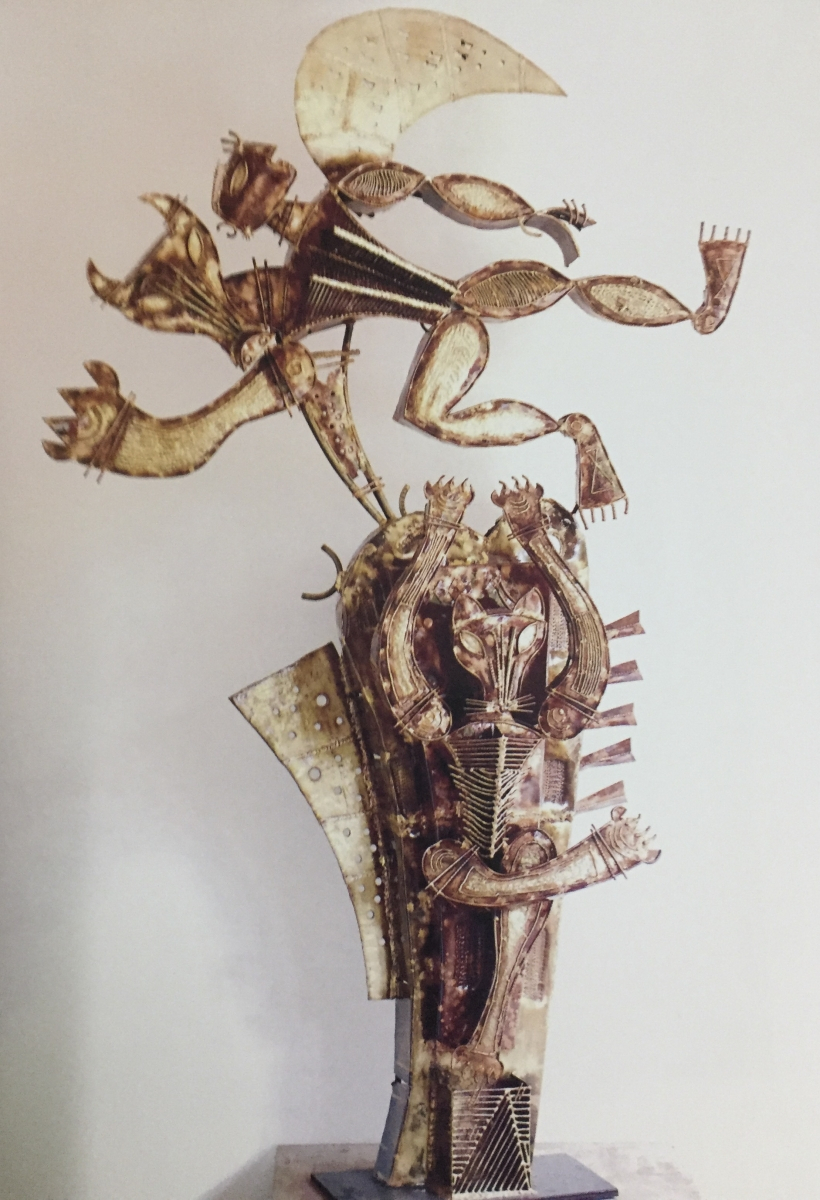

Expanded in scale, Nandagopal's sculptures achieved monumentality; reduced in size, they become toys or jewels. Of the three large-scale sculptures of Nandagopal, 'Tree' (1981) a stainless steel sculpture in the collection of National Center for the Performing Arts, Mumbai (Fig. 11) shares its features more closely with the memories of hero stones series. 'Tree' looks like a gigantic beetle standing on its one leg carrying a cow and a goat with a mesh of arrows kept in between as a flag post. As it is familiar with the Nandagopal's sculptures, the body of the tree beetle is filled with subliminal elements of snakes, triangle meshes, and a wheel that could be mistaken for an eye. While the semiotics of the complex symbolism of the Tree is elusive, its affective dimensions are definitive; it creates a sense of wonderment and exhilaration of seeing a large asymmetrical form balancing on a delicate point. The playfulness of all becomes much more evident in the enormous bell-top Garuda which actually could be of any size. Devoid of his usually complex surface details, Nandagopal’s 'Garuda' sculptures, whether they are small or big, focus on their fierce expressions with minimalist portrayal of their traditional iconography. Unlike the traditional submissive, worshipful Garuda of the temples, Nandagopal's Garuda (Fig. 17) is intense and assertive in its posture and expression.

Fig. 12 (i). 'Monkeys' (1992); Copper, Brass and Enamel; 120 cm; (ii) Watercolour of 'Monkeys'; (iii) 'Hanuman' (1999); Copper, Brass and Enamel

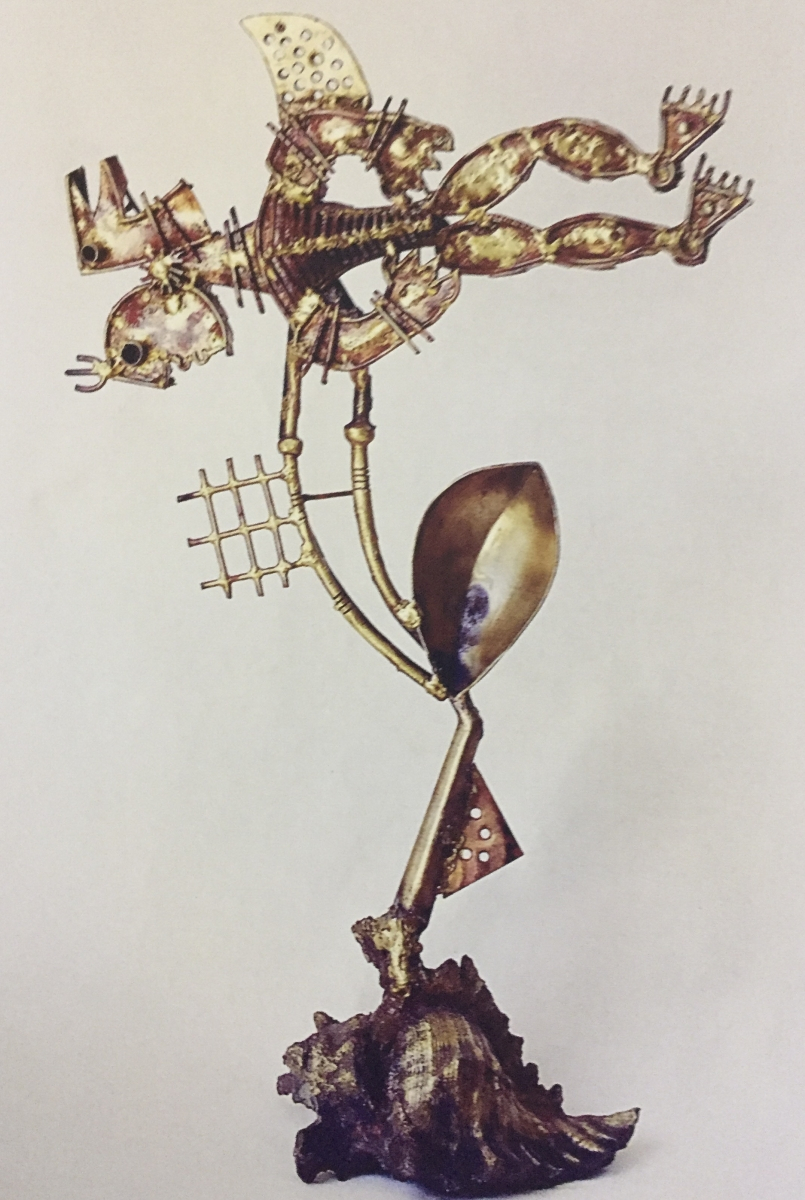

If Nandagopal's Garuda sculptures carry us to see his playfulness and humour in its public prominence, we soon realise the invocation of the comic is an inherent quality of all his sculptures. Nandagopal's playfulness also has an egalitarian impulse, with which he transforms the ordinary into the divine, the commonplace into heroic, and everyday material into a jewel. In the 'Monkeys', a brass, copper and enamel sculpture of 1992 (Fig. 12) we see Nandagopal depicting monkeys playing on a tree. A watercolour picture of the same sculpture exposes the circular joyful movement in the sculpture. The revelry is contagious, and the identical looking monkeys do not single out a hero among them. When one of the monkeys is taken out and presented as Hanuman, we see that it is a joyous doll and a precious ornament at the same time. The basic constituent unit of Nandagopal's visual language, we come to realise, is a jewel in motion. Our notion that Nandagopal unites the ordinary with the divine is further augmented when we compare the structural similarities of three other sculptures: (i) Bhishma version I, (ii) Vishnu, and (iii) Figure on a spoon (Fig. 13). While Vishnu, the Lord is almost hung on the weighing hooks and clipped on to the board with flat spatulas, Bhishma, the legendary warrior and the ultimate Father figure of the Mahabharata and the figure on the spoon are up in the air in a similar fashion, tied so as to stem delicately from a conch. Nandagopal hides his impish humour behind the sculptures just as his profound truth of seeing divinity in everyday objects presents itself in its overpowering radiance.

Fig. 13 (i). 'Bhishma version I; Brass and Copper welded; 46 cm; (ii) 'Vishnu' (2005); Copper and Brass welded; 60 x 94 x 18 cm; (iii) 'Figure on a Spoon' (2001); Copper and Brass welded; Height 60 cm

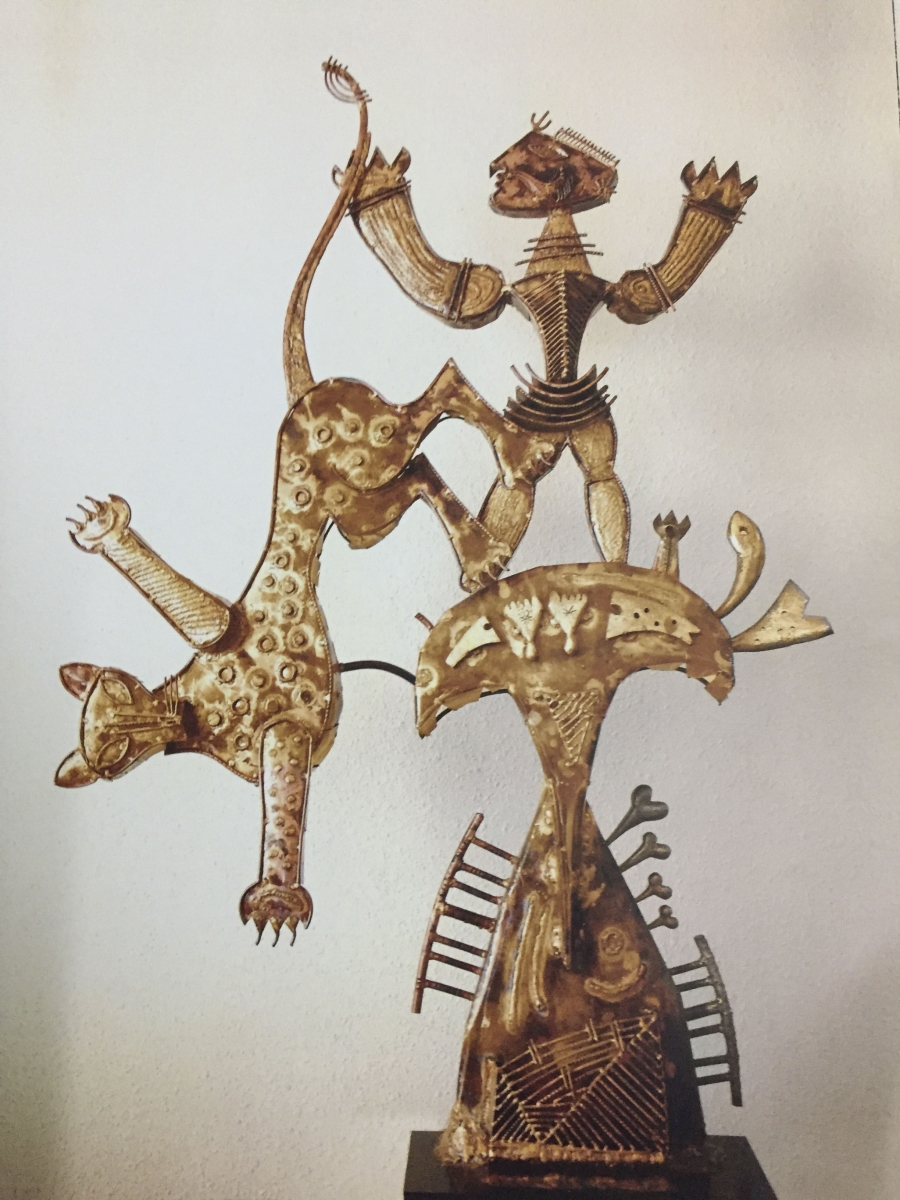

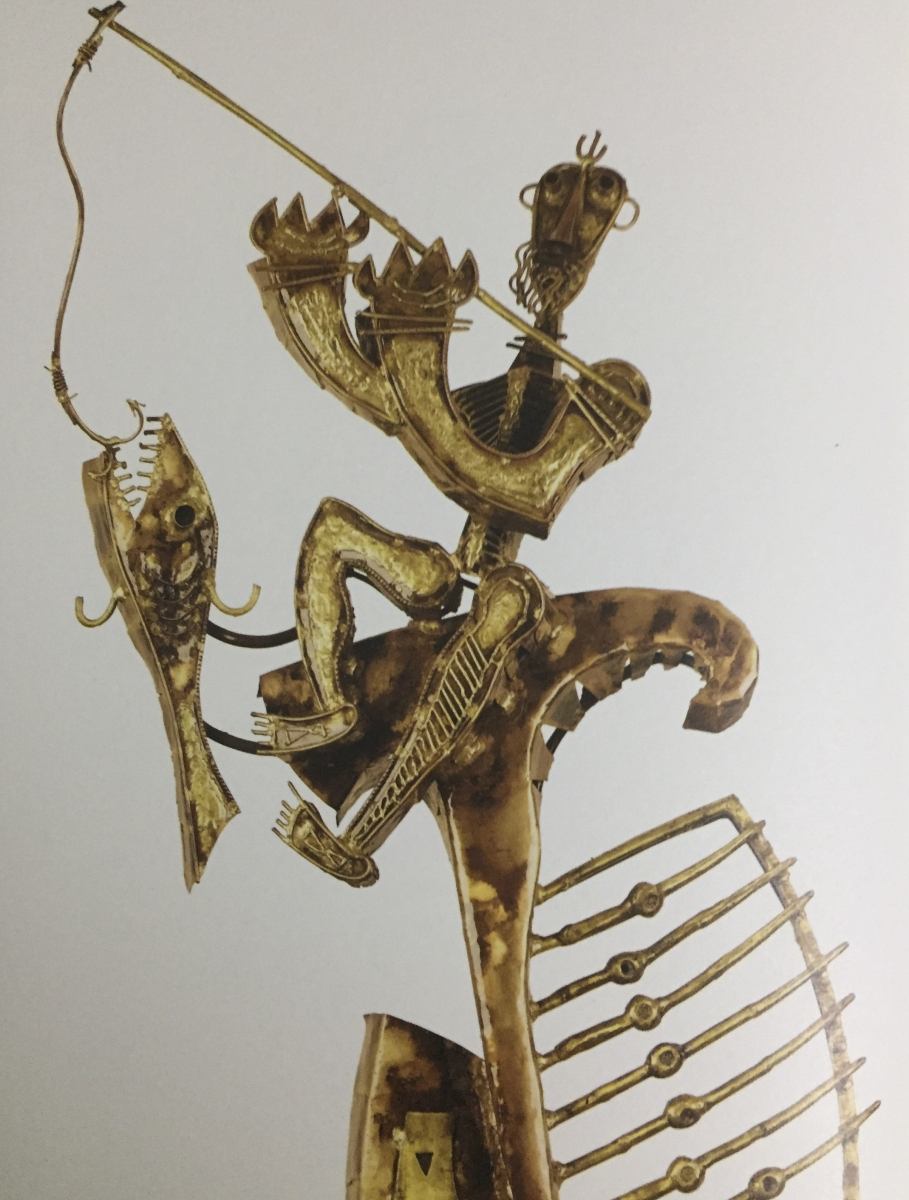

The glossy and shiny surfaces Nandagopal uses for his sculptures for depicting ordinary people such as 'The Fisherman' (2007) and 'Musician' (2007 and 2009) acquire new meanings in the contexts of his endeavours to present memories of the hero stones as the activities of ordinary men in everyday pastoral life. From the 1990s onwards Nandagopal's artistry is to be found in his explorations of the public nature of the sculpture itself. He continuously presented collective memories and metamorphoses in the sculptures this period. In 'Leopard', a copper and brass welded sculpture of 2005, we see the man standing on a totemic mound and holding the tail of the animal is almost an extension of the leopard itself. For Nandagopal, the heroic deeds are when his subjects merge and metamorphose one with the acts they are engaged in. A perusal of the watercolour of Leopard discloses to us that for Nandagopal human actions occur against the background of several memories represented by totemic symbols. Interestingly Nandagopal's small sculpture, 'Head', depicts a panel filled with totemic symbols, which are as much inside the head as much they are outside (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14 (i). 'Leopard'; Copper and Brass welded; 150 cm; (ii) Watercolour of Leopard; (iii) 'Head'; Welded copper, brass and enamels; Height 24 '

Fig. 15. 'The Fisherman' (2007); Copper and Brass welded; Height 100 cm

In the classical Tamil classificatory system of Akam (interior, love) and Puram (exterior, war) poetry and artistic expressions, one would place Nandagopal's sculptures in the Puram, the genres of the exterior. For the Puram artistic expressions, while the public display of the mastery of skills conforms to the ethos of the genre, presentation of internal Akam processes would be against the norms. Perhaps for this reason, Nandagopal presents an acrobat on a wheel, brave encounters with animals and humans in his memories of hero stones in great splendour and wonder-struck detail, but he ridicules Mahabalipuram’s famous public display of stone sculpture, Arjuna's penance in his 'Cat on Penance', a copper and brass welded piece done in 2005.

Fig. 16. 'Cat on Penance' (2005); Copper and brass welded; Height 240 cm

In the Mahabharata, Arjuna undertakes an arduous and punitive penance to acquire the Pasupatha Astra, the deadliest of the weapons that could wipe out the entire humanity from the face of the earth. Arjuna's penance is not about the acquisition of skills or knowledge but about getting magical powers to annihilate his enemies. In Nandagopal's caricature, 'Cat on Penance' (Fig. 15), we see a man merged with an ominous animal carried on the beak of a bird, hovering over the cat's head and making it the subject of the cat's meditation.

Fig. 17. S.Nandagopal with his sculpture 'Garuda'

In an interview with Kathryn Meyers Nandagopal once said, 'Personally I feel that one's art has to reflect your heritage in some way or the other. Günter Grass once remarked that he could never have written, The Tin Drum without the knowledge of a thousand years of German history. In France, in the '60s, there was a movement by some of the artists to actually involve themselves in digging the earth to feel the Celtic soil and to get to their roots which they felt was fast disappearing from their lives.' Faithful to his words, Nandagopal produced his sculptures—whether it is a small toy ornament of a bell-top Krishna or a large monumental and benevolent tree of sculpture—as modernist expressions of Indian heritage and its sensibilities.

Fig. 18. Bell top Krishna (2006); Brass, Copper and Enamels; 40 cm

References

Doctor, Geetha. 2008. Sculptures by S. Nandagopal Past Present in Search of the Heroic. New Delhi: GE Gallaery Espace.

Granoff, Phyllis. 1985 [1980]. S.Nandagopal: A Modern Visionary in an Ancient Tradition. Bangalore: Kala Yatra. Reprint of Art International Essay

James, Josef. 2008. ‘In Conversation with the Artist’. In Nandagopal. New Delhi: Gallery Espace.

Shah, Ranvir. 1993. ‘S.Nandagopal’. In Contemporary Indian Sculpture: The Madras Metaphor. Madras: Oxford University Press.