Little is known about the rich culture and heritage of Jammu and Kashmir which is also perhaps what makes the archaeological and historical study of the state so interesting. Academic research in the state has undeniably been marred by the decades of insurgency it has seen. With scant researches from these fields seeing the light of the day, art and archaeology of the state remains largely unexplored.

The cultural horizons of Kashmir are very broad. Kashmir has archaeological cultures right from the Stone Age to colonial times. The Palaeolithic, Neolithic, Megalithic, early historic and later historic cultures are well attested from a large number of archaeological sites dotting the landscape of Kashmir, which were documented by a few archaeological reconnaissance studies.

Among all the occupation levels (former land surface), the early historical period (early centuries of the Christian era) of Kashmir is the most significant. The surface finds in addition to the excavations conducted at many settlements have produced significant archaeological sources that highlight the nature of historical processes of the early historical period. The most important aspect of the cultural processes of this period is the coming of the Kushanas to Kashmir.

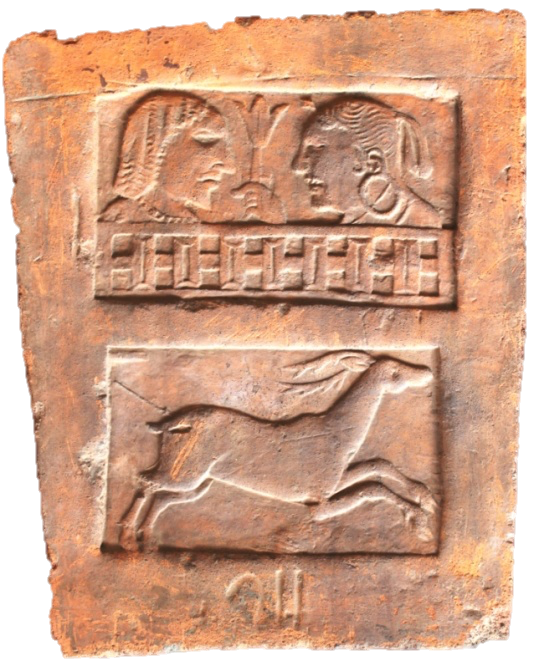

The valley of Kashmir, under the rule of the Kushana kings, saw the rise of the Kashmir terracotta school of art. Instead of stone, which was a popular material for the artists of the Kushana period in the Indian subcontinent, especially those related to the Gandhara School of art,[1] the artists of the time in Kashmir preferred clay as a popular medium for exhibiting their artistic flavours.[2] This is attested by the recovery of enormous terracotta-decorated tiles and terracotta figurines of humans and animals[3] (Figs 1 and 2) as well as terracotta beads, skin rubbers, seals and miscellaneous objects throughout the length and breadth of the Kashmir Valley and its peripheries.

The diaper–pebble style[4] of constructions—along with paving of the Buddhist stupa courtyards with the wedge-shaped, decorated terracotta tiles (Fig. 3)—is an established feature of the settlement pattern designs we come across in the Kashmir Valley and outside, belonging to the Kushana period.[5] Almost a dozen archaeological sites featuring this style of settlement pattern have been unearthed throughout the geographical horizons of the Valley. In some cases, like at Kutbal and Hoinar-Lidroo in the Anantnag district, only the terracotta tile pavements have been recovered. In others, the terracotta tile pavements have been found in association with the pebble and the diaper–pebble styles of constructions. Prominent among the latter are Harwan in Srinagar district,[6] Huthmura[7] and Semthan in Anantnag; Ushkar and Kanispur in Baramulla,[8] and Kralchak in Pulwama district.[9] The tradition of decorating floors with terracotta tile pavements is also reported from Takiya Bala in Pulwama[10], a few closely situated sites at Doen Pather in Pahalgam, Ahan in Sumbal, Bham-ud-din Sahib mosque near Mattan in Anantnag,[11] and Gurwait-Yarikhan in Budgam.[12] Two brick tiles with a cross within a circle were also recovered from Semthan from stratified Kushana levels.[13] Such tiles were also documented from private collections at Semthan and Bijbihara, recovered from the Tengun area of Zablipora. (Figs 4 and 5)

Some aspects of the origin and development of these art forms within Kashmir is discussed by Bandey[14] and its comparisons and other related issues are highlighted by Fisher[15]. These art forms, especially terracotta figurines, bear Hellenistic influence. The Hellenistic ideas of art and learning which left a lasting impression[16] can be traced back to the Gandhara kingdom,[17] of which Kashmir was geographically and politically an integral part. The Gandhara School of art flourished between the first and fifth centuries CE and continued till the seventh century CE in parts of Kashmir and Afghanistan.[18]

Among all the archaeological sites featuring terracotta figurines and tile pavements as their cultural assemblage, Harwan, Huthmura and Semthan are especially significant. Harwan and Huthmura are the two prominent archaeological sites from where the terracotta tile pavements were found in situ in proper stratigraphic context. Semthan is prominent for the recovery of the terracotta figurines of animals and humans, among other objects. Additionally, there have also been important findings from the sites at Kanispora, Ahan, Ushkar, Akhnur and Lethpora.

Harwan was accidentally discovered in 1895 and was subsequently excavated by R.C. Kak in 1920–21. The excavations at the site exposed the ruins of a Buddhist structural complex that flourished around fourth to seventh centuries CE. The earliest and the first of the series of constructional activity at the site was purely of pebble style. An isolated patch of a monastery and a rectangular structure to the north-west of the monastery, laid in north–south orientation on the middle terrace of the site, were in pure pebble style. On the lower terrace of the settlement, two adjacent walls in pure pebble masonry were found. The pebble style was followed by the diaper–pebble style of masonry in 300 CE. On the highest terrace are the ruins of foundations of an apsidal temple built in diaper–pebble masonry. It is surrounded by a courtyard paved with terracotta tiles bearing motifs of humans, animals, birds, flora and abstract designs. Robert E. Fisher has described the structure in the following words:

The rubble-filled walls of the raised apsidal temple, its doorway looking out upon the valley, were probably covered with a layer of smooth plaster and the lowest portions faced with the same terracotta plaques of ascetic figures which surrounded the area on three sides forming a low wall that established the limits of the temple and separated it from the hillside behind.[19]

The area around the stupa, exposed in the lowest terrace of the site, is paved with decorated terracotta tiles which, according to Kak, were broken into pieces bearing figures with incomplete motifs. Kak says, ‘though some [broken tiles] were flat and might have formed part of a pavement, there were a few which bore mouldings in relief and could only have belonged to walls.’[20] It is clear from this statement that the tiles do not belong originally to the courtyard where they were found during the excavations but were probably transported to this place from some other structure of an earlier date.

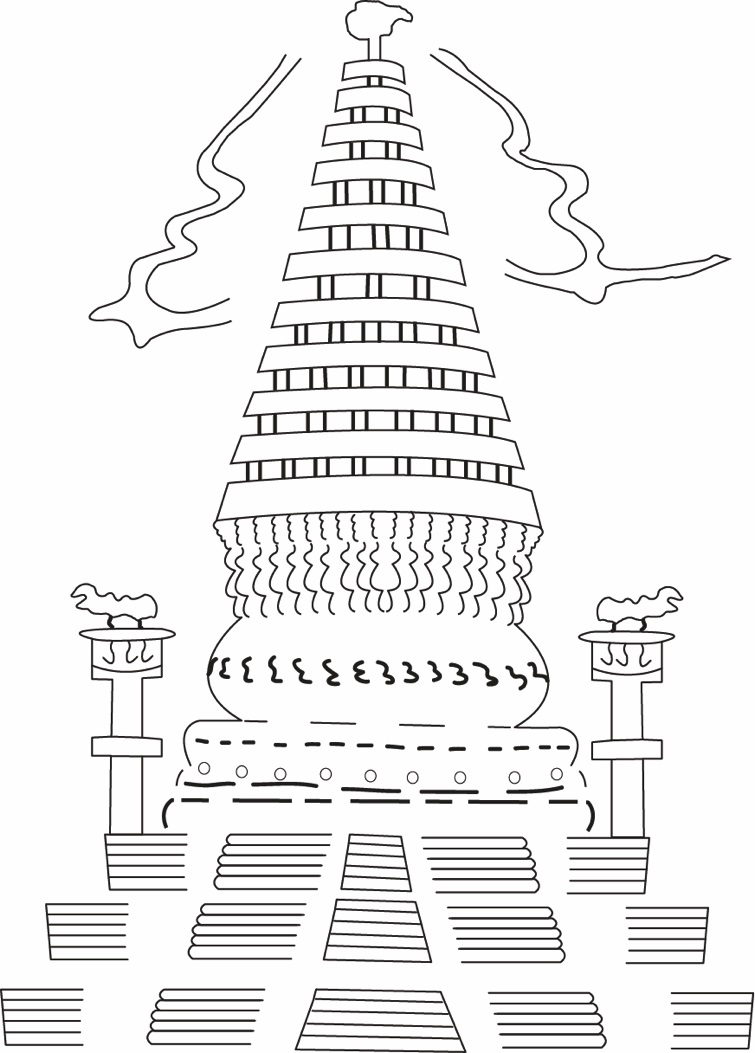

The other finds include several terracotta figural fragments and three plaques impressed with stupa images. These plaques allow us to ascertain the form of a stupa in fifth century Kashmir. (Fig. 6) Pratapaditya Pal describes the stupa depictions on these plaques:

All three [stupas on plaques] have a triple basement with three flight of steps, the drum with a line of beading and plain moldings with plain dome. A row of projecting brackets makes up the harmika, above which is a succession of eleven umbrellas of diminishing size, with fluttering ribbons tied at the very top. At both corners of the top terrace is a tall column with seated lion.[21]

Similar to Harwan, an archaeological site explored and subsequently partially excavated in 1988, is Darad Kut-Huthmura located in Anantnag district. During the trial diggings carried out at the site, the terracotta tile pavements were exposed at three places laid in a systematic plan.[22] The most extensive and the largest among them was exposed on the second and middle terrace laid artistically in nine concentric circles with a diameter of 7.47 metres,[23] with a full-blown lotus in centre. The plan was similar to the tile pavement that was exposed at Harwan.[24] The shape and size of each tile was determined by its position in the circle. The entire tile pavement was demarcated by the pebble style of construction[25] which was further surrounded by a low diaper-rubble wall, measuring 45 centimetres in height and encircling this circular tile pavement.[26] Under this rubble wall, a terracotta spout, originally used to drain out water, was recovered at the level of the tile pavement.[27]

The pebble walls excavated at Harwan are dated to earlier than 300 CE by the excavator.[28] Therefore, the terracotta tile pavement, the pebble structure and the associated material remains at Darad Kut cannot be from later than the fourth century CE.

As in the case of Harwan, the Darad Kut terracotta tiles were also inscribed in Kharosthi numerals and are equally well developed and sophisticated in treatment and fabric. The first and the innermost row of this tile pavement has a three-dimensional full-blown lotus (kamalaghatta) in the centre, surrounded by tiles with lotus petals engraved on them. The second row consists of 12 tiles with depictions of various motifs such as the mythological wishing tree (kalpavrksa) emerging from ‘the vase of plenty’ (puranaghatta). Six tiles of this particular row have cock and swan motifs appearing alternately. The third row comprises 20 tiles. On the upper tier of each tile are motifs of lion and stag facing each other in separate compartments while the lower tier has engravings of different geometric designs. The tiles in the fourth row have floral motifs. The motifs on the tiles of the fifth row are a repetition of the third one. The tiles on the sixth row (Fig. 7)[29] shows three anthropomorphic creatures.

The tile measures 42×30×6 cm. It is wedge-shaped and might have been part of a circular pavement. The portion of the tile bearing the figures is in relief (attached to the background) while the figures themselves are moulded. The relief portion is trifurcated vertically into three separate panels and three human-like creatures are shown standing in different postures. On the extreme right is the figure of a human being, possibly a man with the head of a boar (varaha). The right hand of the figure rests on his raised right knee and the left hand seems rested on his hip. With his eyes fixed on the middle figure of the panel, he seems to be in the middle of a movement. To his right, he is flanked by a figure (perhaps a woman) in a dancing pose with arms up in the air. The figure has a pointed tail which, also up in the air, seems to be in harmony with her performance. The third figure, on the extreme left, is again a man with a smiling face and hair twisted in a projected knot. His right hand rests on his right hip and with his left he holds an object that appears to be a club or an incense burner. Below these depictions are probably some Kharosthi numerals inscribed on the tile giving it the number equivalent to 24. The seventh to ninth rows of the tile pavement at Darad Kut repeats the motifs of the first six rows with slight variations in design and texture. Some motifs on these tiles show human beings with common facial expressions while others have bipedal figures with animal heads and tails. While the pictorial representations on some of the tiles of the early historical period found in Kashmir are stamped, others seem to be made out of a mould, an uncommon practice in Kashmir’s art.

It is also necessary to ask why Kashmiri artists of the period used terracotta instead of stone, the material of choice in Kushana art across the subcontinent. Was it because Kashmir, even before it came under Kushana rule, had an indigenous school of art in which terracotta was in vogue? Evidences seem favourable and convincing. The early historical period in Kashmir had already entered a phase of urbanism before its conquest by the Kushana rulers. There existed a local school of art whose expressions are mostly articulated in terracotta. The Hellenistic features were only an addition to these figurines by the artists who came from the Gandharan territories because of the change in political power and patronage. The tiles show a gradual evolution in terms of surface treatment, from plain to profusely decorated tiles at Harwan, Darad Kut-Huthmura and Semthan. This is supported by Bandey’s argument that Taxila, a Gandharan city, borrowed from Kashmir the technique of making and paving their courtyards with terracotta tiles.[30]

Evidences suggest that the relations between Kashmir and Gandhara strengthened manifold with the arrival of the Kushanas. Influences in art were fuelled by the trade relations between the territories. There was a continuous exchange of ideas, making Kashmir’s art a combination of regional manifestations and foreign influences. [31]

The Kashmir School of art that used terracotta disappeared all of a sudden after the fall of the Kushana dynasty. The Huns are believed to have vandalised many Kushana settlements throughout their empire.[32] There are archaeological attestations of incidents like burning of settlements at Harwan and Darad Kut-Huthmura. Additionally, the coins of the Hun rulers found at Harwan immediately follow the occupation levels of the Kushanas.[33]

There are evidences that suggest terracotta art was present even during the the initial days of the Huns. The excavations at Semthan which led to the recovery of figurines belonging to the fifth century CE and onwards, vindicates this claim.[34]

What happened after that is a mystery. Where did the art vanish? Do we find evidences of such terracotta-making within the geographical horizons and neighbourhood of Kashmir? These are the research questions that await proper probing, explorations and excavations.

Notes

[1] Singh, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India, 462.

[2] Bandey, Silk Route Manifestations in Kashmir Art.

[3] Gaur, ‘Terracotta Art of Kashmir,’ 368–72.

[4] The method of reinforcing a wall of pebbles with the insertion of large and irregular stones at intervals.

[5] Gaur, ‘Semthan Excavation,’ 327–37.

[6] Kak, Ancient Monuments of Kashmir, 105–11.

[7] Pal, The Arts of Kashmir, 55.

[8] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 2; Mani, ‘Excavations at Kanispora,’ 1–2.

[9] Shali, Settlement Pattern in Relation to Climatic Changes in Kashmir, 146–73.

[10] Thapar, Indian Archaeology 1977–78—A Review, 23–24

[11] Bhan, ‘Tile—A Vital Link,’ 47.

[12]The findings of this site were reported in a local daily The Tribune, Jammu, April 30, 1999. A passing reference to this discovery is also mentioned by Ahmad, Ancient Greeks in Kashmir, 161.

[13] Gaur, ‘Semthan Excavation,’ 331.

[14] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 2.

[15] Fisher, Art and Architecture of Ancient Kashmir, 1–16.

[16] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 152.

[17] Singh, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India, 264.

[18] Ibid., 426.

[19] Fisher, Art and Architecture of Ancient Kashmir, 7.

[20] Kak, Ancient Monuments of Kashmir, 106.

[21] Pal, The Arts of Kashmir, 55.

[22] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 2.

[23] Bhan, ‘Iconographic Interactions between Kashmir and Central Asia, 75–90.

[24] Shali, Settlement Pattern in Relation to Climatic Changes in Kashmir, 166–67.

[25] Ibid., 168.

[26] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 2.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Kak, Ancient Monuments of Kashmir, 105–11.

[29] The descriptions of the terracotta tile pavement at Darad Kut and of this tile is mainly based on the writings of Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, and Shali, Settlement Pattern in Relation to Climatic Changes in Kashmir.

[30] Bandey, Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir, 9.

[31] Siudmak,The Hindu–Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences, 32–57.

[32] Dani, Litvinsky, and Safi, ‘Eastern Kushans, Kidarites in Gandhara and Kashmir, and Later Hephthalites,’ 167–87.

[33] Kak, Ancient Monuments of Kashmir, 106.

[34] Lone, ‘Semthan and the Historical Archaeology of Kashmir.’

Bibliography

Ahmad, I. Ancient Greeks in Kashmir. Delhi: Dilpreet Publishing House, 2011.

Bandey, A. A. ‘Silk Route Manifestations in Kashmir Art.’ In Silk Route and Eurasia: Peace and Cooperation, edited by A. A. Bandey, 147–68. Srinagar: Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, 2011.

Bandey, A. A. Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir. Srinagar: Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, 1992.

Bhan, J. L. ‘Tile A Vital Link.’ In Central Asia and Western Himalayas-—A Forgotten Link, edited G.M. Buth, 47. Jodhpur: Scientific Publishers, 1986.

Bhan, J. L.‘Iconographic Interactions between Kashmir and Central Asia.' In Kashmir and Central Asia, edited by B. K. Deambi, 75–90. Srinagar: Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, 1989.

Dani, A. H., B. A. Litvinsky, and M.Z. Safi. ‘Eastern Kushans, Kidarites in Gandhara and Kashmir, and Later Hephthalites.' In History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750, edited by B.A. Litvinsky, 167–87. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996.

Fisher, R. E. ‘The Enigma of Harwen.’ In Art and Architecture of Ancient Kashmir, edited by P. Pal, 1–16. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1989.

Gaur, G. S. ‘Terracotta art of Kashmir.’ In Puraratna: Emerging Trends in Archaeology, Art, Anthropology, Conservation and History, edited by C. Margabhandu, A. K. Sharma, and R.S. Bisht, 368–72. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakshan, 2002.

Gaur, G. S ‘Semthan Excavation: A Step towards Bridging the Gap between the Neolithic and the Kushan Period in Kashmir.' In Archaeology and History (Essays in memory of Shri A. Ghosh), edited by B. D. Chattopadhyaya and B. M. Pande, 327–37. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1987.

Kak, Ram C. Ancient monuments of Kashmir. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2000.

Lone, A. R. ‘Semthan and the Historical Archaeology of Kashmir.’ PhD thesis, Department of History, University of Delhi, 2015.

Pal, Pratapaditya. The Arts of Kashmir. New York: Asia Society and Museum, 2008.

Singh, Upinder. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Delhi: Pearson, 2008.

Siudmak, John. The Hindu–Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. Boston: Brill, 2013.

Shali, S. L. Settlement Pattern in Relation to Climatic Changes in Kashmir. New Delhi: Om Publications, 2001.

Thapar, B.K., ed. Indian Archaeology 1977–78—A Review. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1980.