Satyajit Ray was a legendary filmmaker who influenced directors and actors in India and across the world. During his lifetime, not only did he receive the admiration of his peers, but was also appreciated and supported by influential politicians. Not known to many, the Bengali filmmaker’s work and genius found support and encouragement from two influential women—Indira Gandhi and Marie Seton.

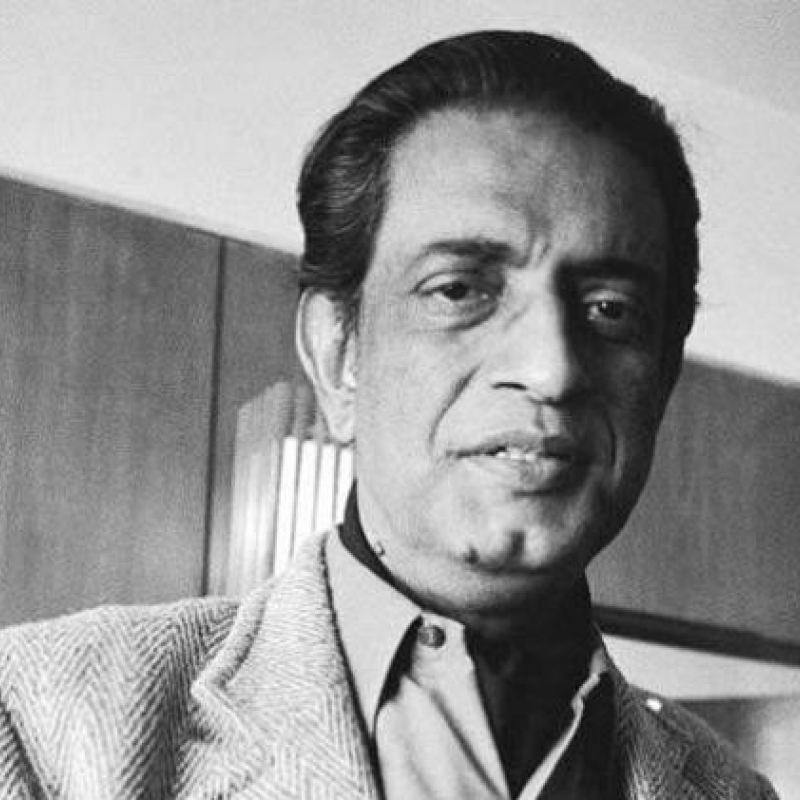

(Photo Source: Dinu Alam Newyork/Wikimedia Commons)

As India sought to rebuild itself post-Independence, its filmmakers found patronage from a rather unusual and enthusiastic quarter—film connoisseurs and cinephiles such as Jawahar Lal Nehru and Indira Gandhi—who helped them reach the global arena. The iconic Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who placed India on the global film map firmly with his epoch-making debut film Pather Panchali (1955), was a product of such patronage. Ray’s early mentors were two influential women—Indira Gandhi, the first female prime minister of India, and Marie Seton, a family friend of the Nehrus and a British film consultant, who had been invited to India in the 1950s to assist the government with the making and promotion of films after penning a biography of the Russian iconoclast filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein.

Unbeknown to many, Gandhi had a keen interest in promoting Indian arts, especially films. In 1952, she brought one of her family friends, Indo-French filmmaker Jahangir Bhownagary, to India to launch the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) under the Films Division. It’s now in its 67th year. Gandhi was in search of talented Indian filmmakers when she came across Ray.

Also Read | The Cinema of Satyajit Ray: In The Prison-House of Humanism

Gandhi was excited about the release of Ray’s Pather Panchali in 1955 and its compassionate portrayal of countryside poverty in India. Seton too was all praises for the film. Having seen it during her multi-city lecture series across India, Seton identified Ray’s film as the neo-realist advent among Indian films and gave a good report to Gandhi and her father, the then prime minister Jawahar Lal Nehru. Those days Nehru not only had the last word in politics, but in the arts and sciences as well. As many critics began to denounce Ray’s debut film for selling Indian poverty abroad, it was Nehru who declared that ‘if a filmmaker shows poverty with such empathy, I am all for it’.

It was because of Satyajit Ray that Marie Seton remained a lifelong Indo-phile and was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1984.

(Photo Source: Calcutta Film Society courtesy V.K. Cherian)

Also Read | The World of Pather Panchali

Gandhi’s and Seton’s relationship with Ray did not end with Pather Panchali. Soon, after Seton heard of the Ray film in August 1955, she went to Kolkata to revive the Calcutta Film Society. The film society had been established in 1947 but had stopped activities as its founders were busy making their debut films in the early 1950s. Seton went around Calcutta (now Kolkata) and wrote the first English biography of Ray, Portrait of a Director – Satyajit Ray, in 1971. It was because of Ray that she remained a lifelong Indo-phile and was awarded the Padma Bhushan—the third highest civilian award in India, in 1984. ‘After her first visit (in 1955, the year Pather Panchali was released), Marie Seton developed such an attraction for India, she virtually become a citizen of this country’, Prof. Satish Bahadur of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) wrote in his centenary tribute to Seton in The Hindu in 2010.[i]

Indira Gandhi (left) had a special relationship with Satyajit Ray (right); being a huge admirer of his films, she also heeded his counsel on all matters related to the Indian film industry (Photo Source: Calcutta Film Society courtesy V.K. Cherian)

Gandhi too had a special relationship with Ray and was a huge admirer of his films. Surely, she appeared to be all ears for Ray and pushed all issues in his name to make the Film Society Movement the toast of the 1960s and 1970s. In December 1959, when the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI) was being formed, Gandhi—who had not yet joined politics—agreed to become FFSI’s vice-president for a brief period when she was told that Ray was the president of the organisation. Ray’s presence at FFSI and Gandhi’s admiration for his films ensured that film society movement had all the patronage from the government of the day. ‘She suggested, getting her a letter from Manik da on this and Manik da was ever obliging as President of FFSI. And Mrs Gandhi as Information and Broadcast Minister waived off censorship for film society films’, Vijay Mulay, a long-time activist of Delhi Film Society said in an interview.[ii]

Also Watch | Satyajit Ray Through a Filmmaker's Lens: Conversation with Tarun Majumder

Gandhi consulted Ray even with key appointments in film institutes and departments. In the early 1960s, Ray recommended Ritwik Ghatak, an equally bright filmmaker from Kolkata, to be sent to the newly started FTII at Pune, as its vice-principal. Gandhi gladly obliged. Ghatak made brilliant films, but most of them, barring one, fared badly at the box office and no film producers in Kolkata were willing to fund his films. Though Ghatak spent only a few years at FTII, they were enough to inspire the first few batches of students at FTII. In Ghatak, India got its mentor for the ‘new wave’ of films as both Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, the prime proponents of Indian parallel cinema remained Ghatak’s lifelong fans. Ironically, Ray was occasionally acerbic towards Ghatak. ‘It is strange that both Kaul and Shahani should acknowledge their tribute to Ritwik Ghatak, who taught them at Poona,’ Ray wrote in his book Our films, Their Films (1976), ‘when the only Ghatak trait they seemed to have imbibed is a lack of humour’.

Both Gandhi and Seton remained lifelong admirers of Satyajit Ray, who remained the FFSI president for the rest of his life. Even today, Seton’s biography is still one of the most authentic accounts of the filmmaker’s life. Together, the triumvirate represent Indian cinema and its growth during the first three decades after Independence—often deemed as the golden era of Indian cinema.

Views expressed are personal.

[i] Satish Bahadur, ‘Pioneer Remembered’, The Hindu, New Delhi, March 4, 2010, https://www.thehindu.com/arts/Pioneer-remembered/article16483563.ece.

[ii] V.K. Cherian, India’s Film Society Movement: The Journey and its Impact (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2017), 50.