As Shakespeare never exhausts his supply of 'horn' jokes for mocking cuckoldry, the satirist of contemporary fashions relies without fail on the mistaken sexual identity.

—Susan C. Saphiro[1]

Perhaps the most hackneyed subject of ridicule in a satire of any form, from any part of the world, is the woman who forgot her place. Thus, Saphiro’s frustration with the repetitiveness of ‘Punch’ cartoons poking fun at the woman who wears a man’s clothes is entirely understandable. In cultural studies, Punch magazines have been regularly revisited for their representation of the ‘new woman’—the educated, liberated and opinionated woman who began asking for her rights—as she emerged at the end of the nineteenth century in England. So, when the Indian vernacular press started to bring out its own Punch magazines and their ilk in retaliation of the stereotyping and ridiculing of the colonial subjects by the British Punch, the ‘new woman’ trope too got imported and transcultured.

In the long tradition of Bengali anti-colonial cartooning (beginning in 1872 and continuing into the last decades of India’s fight for independence), these cartoons can be read in three ways: sociologically, politically and semiotically. In the sociological reading, we take them as reflections of social phenomenon and, more particularly, the moralities of the society. Studied politically, they reflect subtle power hierarchies; cartoons, like most visual texts, privilege certain points of view over others and unpacking these power structures within the frames of the cartoons is an important political exercise. Finally, semiotically, cartoons use standardised signs to put across messages that create the satire; certain signs in cartooning signify certain meanings, and it is very important that these meanings remain consistent to a particular culture, so as to convey the humour of the artist. However, this essentially requires that the cartoons be dependent on dominant ideologies, moralities and social practices of a society and, thus, inclined to ridicule anything that challenges the authority of these principles. It is this manipulation of signs that Subhendu Dasgupta explores in his book Chinho Bodol, Chinho Dokhol[2]. The representation of women in caricature in Bengal has been widely misogynistic as Dasgupta points out in the introduction of his book, and while caricature in general has had little scholarship on it, women’s representation in cartooning is a matter further ignored.

The Interaction of the Bengali Middle Class with Print

As historian Anindita Ghosh points out, the technology of vernacular print created a social hierarchy within the Bengali public sphere.[3] The consumers of certain standardised Sanskritised Bengali became the dominant sociopolitical group, and the texts published by the Battala printing culture—the cheap and often promiscuous literature consumed and produced widely by women and other marginalised sections of the demography—remained a thriving counter-cultural response to the middle-class Bengali bhadralok.

The public sphere of the Bengali bhadralok reforming the Bengali society in the late nineteenth century was repeatedly threatened by the existence of the subversive print culture of the Battala press. The bhadralok visibly distanced himselves from these ‘cheap literatures’, at least in public; the women of the antahpur (the inner sanctum of the house which was their space), however, continued to consume this literature widely. Battala publications, with their use of a commonly spoken Bengali dialect instead of the Sanskritised Bengali, were not only linguistically different from the public language of the bhadralok but also dealt in issues of questionable morality. They explored sexuality, promiscuity and marital relationships with little concern for the Victorian morality that the colonial Bengali bhadralok was desperately trying to appropriate in his attempt to modernise his society. This is important because caricature belongs essentially to the public realm of the Bengali bhadralok; in fact, one of the first Punch magazines in Bengali was published by Gaganendranath Tagore, a member of the illustrious Tagore family of Bengal, which assumes a canonical status in the minds of Bengalis across the globe. In the public realm, the patriarchal bhadralok was attempting to reform the vices that did not suit the narrative of modernity that he was trying to construct; the Bengali Punch cartoons of the late nineteenth century that dealt with the female subject painted her as the embodiment of these vices. The public space was essentially male, and looking within at the private female domain, the male gaze of the bhadralok caricaturist found a lot to disapprove and rectify.

New Women, Old Jibes in ‘Modern’ Bengal

The representation of political cartoons from the period of India’s independence struggle showed women either as the symbol of moral decadence in the society or the victim of it. The Bengali bhadralok, invested in the attempt to reform his society along the lines of Western Enlightenment that colonial education had initiated him into, found the woman an easy receptacle to which he relegated the problematic, creating a neat impression of a modern society; further, she was also simultaneously the project of this modernity. Her emancipation, education and empowerment were markers of modernity; the middle-class bhadralok, in saving her, saved his society from being condemned to the dark premodern. The woman was both the problem and the project, a belief widely popularised by the cartoons of the era.

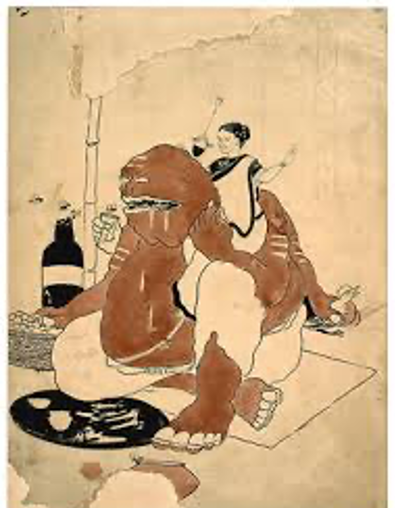

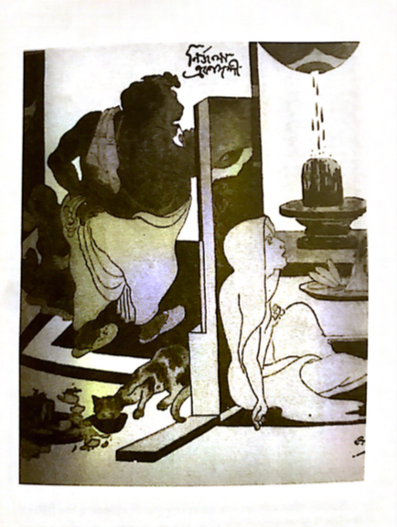

For example, Gahanar Hisab Poriya Swami Hatabhabmba, Grihini Phanka Mone Abhimanini (Husband thunderstruck at the cost of jewellery while wife is still recalcitrant and upset), a cartoon published in the Bengali language magazine Banganibashi, in 1893, shows a husband appalled by the cost of jewellery purchased by his wife and the fact that her material desires are still unsatiated. (Fig. 1) This obsession of the woman with material comforts suggested a spiritual corruption. Her agency in the spiritual decadence of the society becomes much more prominent in Kalijuger Brahman, a cartoon published by Gaganendranath Tagore in Adbhut Lok, where, among the other things corrupting the Brahmin, is also a woman actively doing away with the spiritual texts. (Fig. 2)

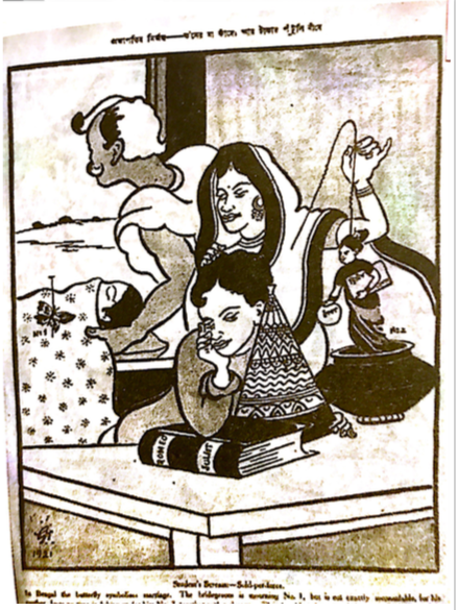

Tagore also painted the picture of the woman oppressed by Brahmanism in Bengali society repeatedly, such as in the cartoon The Brahmin and the Widow, where the Brahmin priest is finishing a hearty meal and a child widow is forced to observe a fast (Fig. 3), and the cartoon Matrimonial Scream—Marriage Reform, published in Naba Hullor, where a child bride is married off to a tin of kerosene oil (Fig. 4). In these caricatures, there is a sharp critique of the practice of sati and dowry. In another of Tagore’s works, Srudem’s Scream—Sold-per-force, the child bride is shown lying dead while the husband, who is reading Romeo and Juliet as a symbol of his Western education, is already preparing to marry another child who will bring him more dowry. (Fig. 5)

This dichotomy of the woman simultaneously embodying the corruption of Bengali society and being oppressed by it charged most of this project of emancipation. However, this emancipation did not necessarily permit the woman to join the public sphere. While the new woman was more widely appreciated in the Bengali society than her English sister, as soon as she stepped into the public sphere and began appropriating the male symbols, she became a subject of ridicule. Take, for example, Jyotindra Kumar Sen’s Nari Bidroho (Women’s Rebellion) published in 1919 and Benoy Kumar Bose’s Ekobingsho Shotabdite Nari-choritam (Character of Women in the Twenty-first Century) published in 1927: while discussing these cartoons, Subhendu Dasgupta[4] calls them subversive, however, what is most striking about them is that to ridicule a woman, the cartoonists drew her as ‘acting like a man’. These women were working professionals, who wore functional clothes and brought home men they married, in short, strutting the domain of the man.

The image of the lady clerk (Fig. 6) in Bose’s work of the same name inspires a long discussion by Dalia Chakraborty[5], and she looks at the sociological meanings of the ‘working woman’ in the early twentieth century. Yet, in a detailed discussion of the social dynamics of colonial Bengal in the inter-war era, what she misses out is the need for the cartoonist to give the clerk a masculine gait and near masculine clothes. The Bengali cartoonist’s motives behind creating these caricatures mirror the anxieties he shared with the middle class in the metropolis of London, when inter-war circumstances propelled women to join the workforce outside their homes and voice their opinions in the public sphere. While initial Bengali cartoons began by wanting to educate the woman and liberate her from Brahmanical oppression, as soon as she stepped into a public life, she became an object of ridicule much like her English sister in the British Punch: the woman who forgot her place and appropriated symbols of masculinity, such as the clothes, the stride and the black umbrella of the Lady Clerk. Thus, the art form that began as a form of resistance against the colonial narrative, emulated the ‘original’ in form and content, and often uncritically.

Away from the controlling gaze of the bhadralok’s women emancipation project, the Bengali woman’s only respite was in the thriving subversive cultures of cheaper prints brought out by the popular Battala press, which embraced in both tone and content the politics of the antahpur.

Notes

[1] Saphiro, ‘The Mannish New Woman Punch and Its Precursors,’ 1.

[2]Dasgupta, Chinho-Bodol Chinho-Dokhol, 9.

[3] Ghosh, Power in Print.

[4] Dasgupta, Chinho-Bodol Chinho-Dokhol.

[5] Chakraborty, ‘The Cartoon of a Bengali Lady Clerk.’

Bibliography

Chakraborty Dalia. ‘The Cartoon of a Bengali Lady Clerk: A Repertoire of Sociological Data.’ Sociological Bulletin 53, no. 2 (May–August 2004): 251–262

Dasgupta, Subhendu. Chinho-Bodol Chinho-Dokhol. Kolkata: Monfokira Publishers, 2017.

———. Gaganendranath Thakur-er Cartoone Hindutwobad. Kolkata: Boipattor, 2018.

Ghosh, Anindita. Power in Print: Popular Publishing and the Politics of Language and Culture in a Colonial Society. New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Gupta, Abhijit, and Swapan Chakraborty. Print Areas: Book History in India. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004.

Shapiro, Susan C. ‘The Mannish New Woman Punch and Its Precursors.’ The Review of English Studies 42, no. 168 (1991): 510–22.