Political caricature was introduced to the Indian subcontinent by the British colonisers in the second half of the nineteenth century. The railways, the telegraph and the printing press that were introduced by the British to help the imperial project in India went on to become critical apparatus in the formation of nationalist consciousness. Similarly, cartooning went on to assume severe nationalist overtones as more and more Indians began drawing and publishing political cartoons in periodicals and in the form of books or albums. The British Punch magazine, a weekly that began publication in 1841 in London, routinely derided the colonial subject and caricatured it in several ways. Soon, as an attempt to respond to this humiliation, vernacular ‘Punch’ magazines and political cartoons in various newspapers began to be published. The first of these dissenting cartoons in an Indian publication was published in 1850 in the newspaper Delhi Gazette. In 1872, the first Bengali cartoon was published in the newspaper Amrita Bazar Patrika, commencing a long legacy of cartooning in Bengal. [1]

However, despite their significant role in shaping the consciousness of the nation, political cartooning in India has not been studied extensively as an academic field of enquiry, and vernacular cartoons even less so. Pioneering works in the study of vernacular cartoons include American anthropologist Ritu Gairola Khanduri’s book Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World and historian of colonial north India, Mashirul Hassan’s work focussing on the Punch magazines in northern[2] and western India[3]; these works agree that the development of vernacular Punch magazines and caricature in India was an outcome of growing dissidence against the colonial government in India.

Bengali cartooning had similar beginnings in voicing anti-colonial sentiments. The first attempt to anthologise these cartoons was made by the renowned cartoonist of postcolonial Bengal, Chandi Lahiri. He anthologised the cartoons published in the magazine Basantak and attempted to annotate these. In his book Bangalir Rongo-Byango Chorcha, he attempted to paint the larger picture of practices of wit and humour in Bengal, like Mashirul Hassan does for the other regions. But, academic and systematic enquiry into these cartoons have been a recent phenomenon led by professor of economics at the South Asian Studies department at University of Calcutta, Dr Subhendu Dasgupta. In recent times, sociologist Dalia Chakraborty’s study of women’s representation in the Punch cartoons[4] and art historian Partha Mitter’s analysis[5] of the cartoons as transculturation of the Punch magazine into colonial Bengal are notable academic endeavours on the topic; Mitter’s is a fascinating study of how the art form introduced by colonisers became an anti-colonial apparatus, used to ridicule and question the British governance.

The Chronology of Political Caricature in Bengal

To look at the cartoons as simultaneously a reflection and an apparatus of the middle-class cultural ethos in colonial Bengal, it is important to divide them into three distinct historical phases of anti-colonial movement in Bengal. The first is the phase between 1872, when the first Bengali Punch cartoon was published, and 1910; this phase marks the development of nascent political aspirations within the Indian subcontinent in demanding self-governance. With the suppression of the Revolt of 1857, the handover of power from the East India Company to the Queen and parliament, and a general ushering in of political modernity in the subcontinent, there was a characteristic change in the public sphere and political aspirations of the Bengali colonial subject, which reflected in the cartoons of this era.

The second phase begins in 1910 and ends in 1930. The opening decade of the twentieth century saw the rise of radical nationalism and the demand for swaraj. This political demand was fuelled by the Swadeshi programme, a declaration of boycotting all British goods and embracing Indian products. The cultural spectrum saw a similar movement with the Bengal school of art developing and finding inspiration in Mughal miniatures and other pre-colonial classical art schools in India; this is reflected in the political caricature of painter and cartoonist Gaganendranath Tagore, an eminent member of the Bengal school of art, known for his stylistic contribution to modernising political caricature in Bengal.

The final decades leading up to Indian Independence, Partition of the subcontinent, and formation of the constitution were marked by the need to define a coherent Indian identity and Indian national consciousness that were not dependent on the antagonism against the colonial government. Contesting opinions on secularism, religious differences and economic organisation—mainly the contradictions between socialist economic criticism of the British and the mainstream nationalist criticism which focussed on political independence—featured in the cartoons of this era.

1872–1910: Growth of nascent nationalism

The beginning of cartooning in the subcontinent in general and in Bengal in particular was not an isolated event, neither was it a pure reproduction of the art as brought in by the British colonisers. Bengal had a long history in caricature in the folk art form of patachitra. The development of woodcut paintings in Kalighat in the nineteenth century showed a distinct presence of the sociopolitical realities of the day as caricature. While the paintings started off as colourful depictions of gods, goddesses and mythologies, they soon began catering to contemporary demands and reflected everything from ‘henpecked husbands’ to crime scenes. The introduction of lithography in the 1860s also facilitated cheap printing in the subcontinent, providing access and market for books from the Battala press situated in North Calcutta. The Battala press (literally, a press under a banyan tree) was actually a number of cheap printing establishments in a stretch along the northern part of the city, publishing promiscuous works of literature. The Battala publications were consumed by the women and lower classes of the city that were not exposed to the perceived refinement of Western education and political thought; these texts reflected a certain assertion of the politically marginalised as they subverted the dominance of the middle-class Bengali bhadralok in the more formal print cultures and political public spheres. Interestingly, caricature, though an art of subversion, remained the domain of the bhadralok.

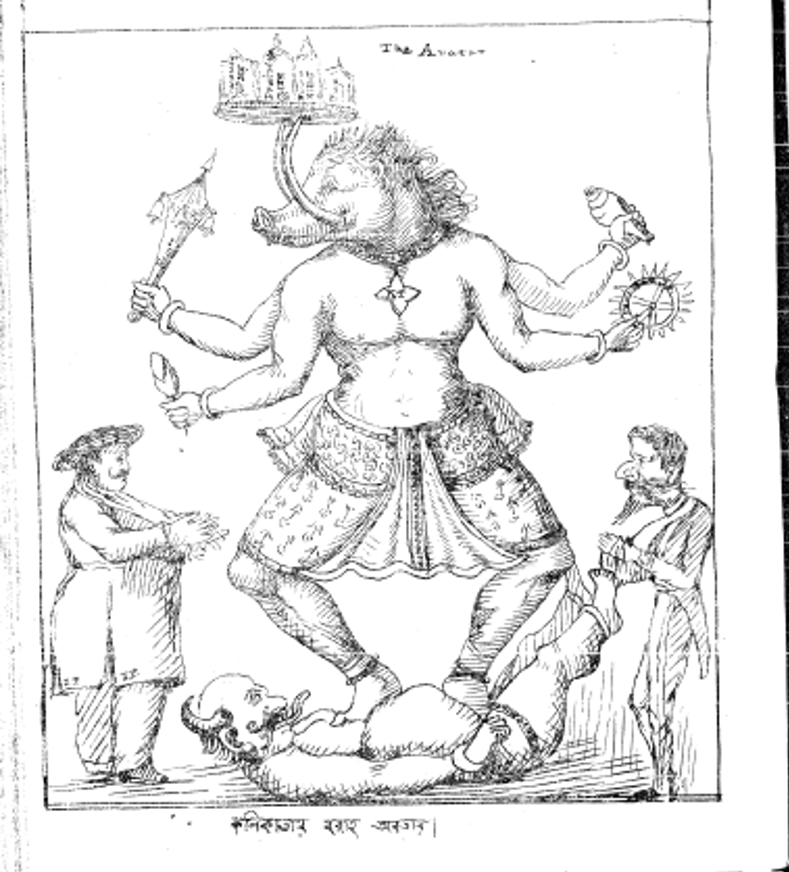

The introduction and wide circulation of the British Punch magazine caricaturing the colonial subject was the final straw that necessitated an answer to the colonial discourse. In 1872, Amrita Bazar Patrika published a caricature of the then Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, Sir George Campbell, which started a trend. A growing demand for the right to participate in the municipal elections of Calcutta, known as the ‘municipality movement’, soon led to the birth of two periodicals, Harbhola Bhanda and Basantak, that published satire and cartoons in Bengal in 1874. Basantak was run by the Dutta brothers of Hatkhola, Prananath Dutta and Girindranath Dutta, and these editors were also simultaneously leading activists in the municipal movement in Bengal. Basantak regularly criticised the British city officials like Sir Stewart Hogg, who was once caricatured as the Baraha (pig) avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, playing on his surname, pronounced as ‘hog’; even Brahmo Samajists and police officials were criticised by the Basantak. (Fig. 1) Dubbed the first Indian Punch, Basantak found wide circulation and resonance in Calcutta’s bhadralok society. It is interesting to note that these dissenting cartoons were published by a growing middle class in Bengal and not the marginalised voices that otherwise found expression in the Battala publications. These were cartoons for the literate, for the trained, and for those with political and social aspirations. They bore political messages that required a sense of awareness and a Western training in political thought—of democracy, self-rule, rights, duties and citizenship that these cartoons were discussing in context of British colonial rule.

1910–1930: Radical swadeshi Gaganendranath

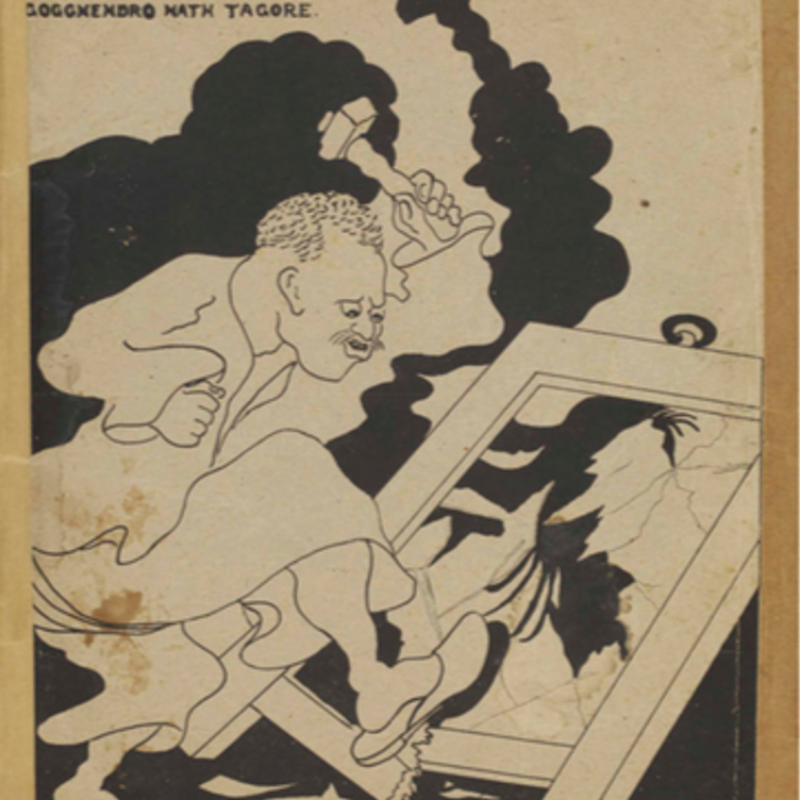

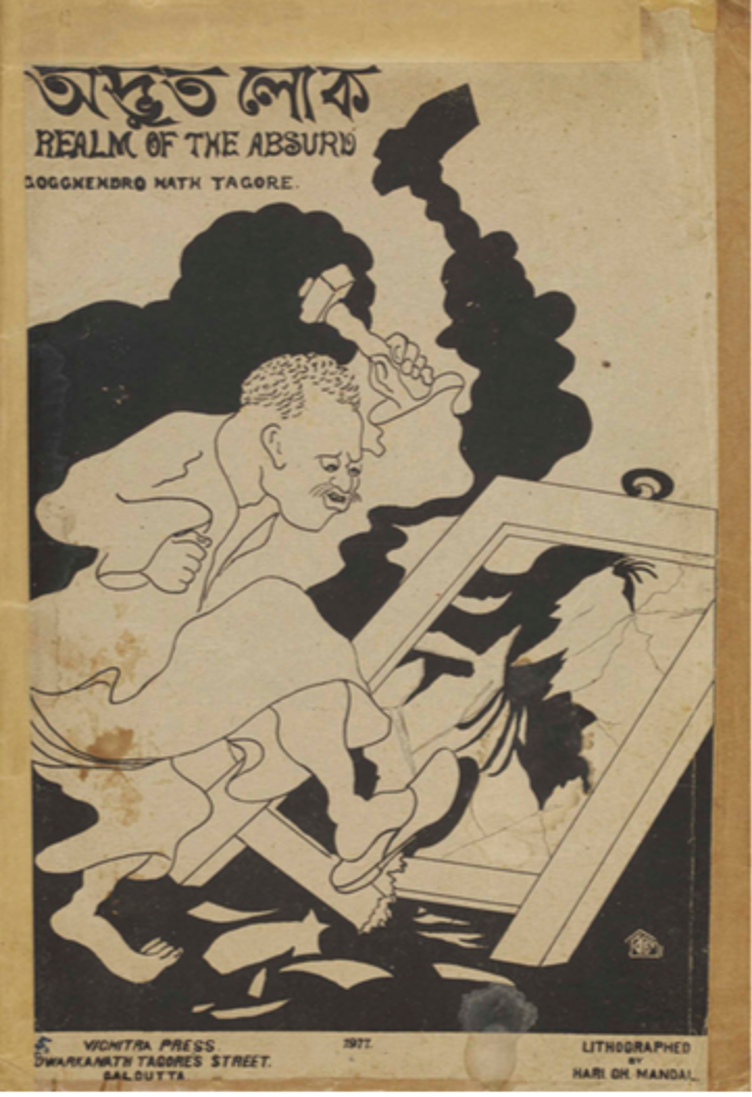

Perhaps no single family in Bengal, before or since, have embodied change and modernity as the Tagore family of Jorasanko. Besides the illustrious poet Rabindranath Tagore, who achieved iconoclastic importance in Bengali culture, the family had several figures who revolutionised the Bengali middle-class cultural ethos. With the presence of a strong and ongoing Swadeshi movement, Rabindranath’s nephews, Abanindranath Tagore and Gaganendranath Tagore, formed the Bengal school of art that broadly rejected European styles and found inspiration in India’s pre-colonial artistic techniques. The poet Rabindranath, himself an artist of renown, was ambivalent to the idea of swadeshi and both his novels on the subject, Gora and Ghore Baire, reflect similar sentiments. He is said to have remarked that nephew Gaganendranath was ‘radically swadeshi’, perhaps with a hint of dismay. Gaganendranath, however, did not wait for his uncle’s approval; with the advent of lithography, he began publishing cartoon magazines that mercilessly attacked not only the British coloniser but also the anglicised Bengali. He attacked with equal gusto the various social evils that plagued the Bengali society: brahmanism, patriarchy and anglicisation. From 1917 onwards, Gaganendranath published three books, Birup Bajra, Naba Hullor and Advut Lok. (Fig. 2) He also published in several periodicals such as Probashi and Modern Review. Gaganendranath brought a distinct modernity to Bengal’s art; while his subject was strongly anti-colonial, the art developed strong shades of the European style that the New Zealand-born British cartoonist David Low and his anti-fascist cartoons was later famed for.

This is not only important as a change in the form of art but also in our understanding of the critical shifts in the public sphere. Political discourse in India of the opening decades of the 1900s began using the language of Western political modernity and its concepts like liberty, equality and rights of citizens as a tool against colonial rule. In essence, the knowledge derived from Western society began to inform anti-colonial discourse. A similar trend is seen in Gaganendranath’s cartoons, which are modelled more on a British style than on the local Kalighat patachitra but seem to question the anglicisation of the Indian in content. Gaganendranath’s cartoons decidedly do away with bold lines, bright colours and mythological characters, and assume a very European minimalist and realist style. The content, however, reflects a strong disdain for the anglicised Indians who gave up their traditions and customs to adopt the masters’ language. For example, in a cartoon published in 1915–16, Gaganendranath drew an Indian man dressed in European clothes in distress and captioned it: ‘By the sweat of my brow I try to dress like a Sahib but that man calls me Babu’, a joke on the anglicised Bengali because, as his uncle Rabindranath said, ‘Gagan is radically swadeshi’.

So, Gaganendranath was swadeshi in content and European in style. As the bhadralok’s nationalism grew politically virulent, he became increasingly dependent on Western political thought to justify it. This fractured identity continued to haunt the Bengal public sphere up to Independence and beyond.

1930–1947: Whose India is it anyway? The socialist aspiration of Chittoprasad’s pen

The Lahore session of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1930 declared the demand for absolute independence, marking the beginning of the last phase of colonialism in the subcontinent. In the closing decades of colonial rule in Bengal, the public sphere sprang to life debating the vision of India, and there was visible political split in the anti-colonial struggle. The socialists pulled out of the Quit India movement launched by Gandhi in 1942, and the Forward Bloc and the Indian National Army led by Subhas Chandra Bose attempted an armed attack against the British government. The proposed ‘two-nation theory’ also fractured the long-standing Hindu-Muslim unity of the anti-colonial movement. Finally, the man-made famines of 1942–43 ruined the rural economy in Bengal. These political events found deep resonance with the cartoonists of the era. Yugantor, the Bengali daily from the Amritabazar Patrika group, opened up to famed cartoonists including Revati Bhushan, Kafi Khan, Amal Chakraborty and Saila Chakraborty. Yugantor cartoonists brought with them a new lexicon of nation building that went beyond criticising the British and focussing on the idea of nationalism. While some openly supported the two-nation theory, others contested this with a more secular outlook. The most striking images, however, were the works of the socialist artist Chittoprasad Bhattacharya. He covered the Bengal Famine extensively in simple pen-and-ink drawings. Easily reprinted in cheap copies, these were used by the Communist Party of India (CPI) as socialist propaganda against the colonial government as well as the Indian National Congress, which was perceived by the socialists to be an ally of the British ruling class. The striking factor about most of Chittoprasad’s work is that it was made to mobilise and organise rather than express opinions, criticise or simply produce humour, in fact, much of these cartoons were not even humorous.

The closing decades of colonial cartooning in Bengal differ largely from the cartoons published by Sankar, often called the father of political cartooning in India, and others in English newspapers in one primary respect: while English cartooning dealt with political concerns, Bengali cartoon developed a lexicon of economic criticism as well. This, however, was not a legacy that survived. Political cartooning as a tool to mobilise and organise political opinions remained a largely unused apparatus.

Cartoons in Colonial Bengal: A Middle-class Culture

Anindita Ghosh in her book Power in Print talks of the hierarchies of language introduced by print in late nineteenth-century Bengal.[6] The language in print was changed vastly by standardisation and Sanskritisation of Bengali middle-class literature, whereas cheaper and more vulgar literature published in Battala by marginal populations and women were written in a different language that was more commonly the spoken dialect. Cartooning as an art of dissent has always been thought of as originating from the margins of society and voicing concerns against the oppressor. While cartooning in Bengal did play a similar role in developing criticism against the British, it was never a mass culture. Cartooning was limited to the Western educated, politically conscious middle class that read print and subscribed to periodicals. Unlike the more folk forms of caricature like patachitra, the caricature in Bengali Punch magazines was an upper-caste Hindu middle-class pursuit. This is reflected in the astonishing diffidence to accord women equality of representation; in the near absence of Muslim voice, despite Bengal being a Muslim majority province; and the readiness with which bhadralok cartoonists accepted Western styles abandoning patachitra. Cartooning in colonial Bengal was an art of dissent but never an art of the masses.

Notes

[1] Harder and Mittler, eds., Asian Punches.

[2] Hasan, Wit and Humour in Colonial North India.

[3] Hasan, Wit and Wisdom.

[4] Chakraborty, ‘The Cartoon of a Bengali Lady Clerk.’

[5] Harder and Mittler, eds., Asian Punches.

[6] Ghosh, Power in Print.

Bibliography

Chakraborty, Dalia. ‘The Cartoon of a Bengali Lady Clerk: A Repertoire of Sociological Data.’ Sociological Bulletin 53, no. 2 (May–August 2004): 251–262.

Dalmia, Vasudha. The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions: Bhāratendu Hariśchandra and Nineteenth-Century Banaras. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Ghosh, Anindita. Power in Print: Popular Publishing and the Politics of Language and Culture in a Colonial Society, 1778-1905. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Gupta, Charu, ed. Gendering Colonial India: Reforms, Print, Caste and Communalism. Critical Thinking in South Asian History. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2012.

Harder, Hans, and Barbara Mittler, eds. Asian Punches: A Transcultural Affair. Heidelberg: Springer, 2013.

Hasan, Mushirul. Wit and Humour in Colonial North India. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2007.

———. Wit and Wisdom: Pickings from the Parsee Punch. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2012.

Khanduri, Ritu Gairola. 'Vernacular Punches: Cartoons and Politics in Colonial India.' History and Anthropology 20, no. 4 (December 2009): 459–86.

———. Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Naregal, Veena. Language, Politics, Elites and the Public Sphere: Western India under Colonialism. London: Anthem, 2002.

Orsini, Francesca. The Hindi Public Sphere 1920–1940: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Sunderason, Sanjukta. 'Arts of Contradiction: Gaganendranath Tagore and the Caricatural Aesthetic of Colonial India.' South Asian Studies 32, no. 2 (July 2, 2016): 129–43.