Photo courtesy Rupayan Sansthan

(With inputs from Vishal Pratap Singh Deo, Kuldeep Kothari, Ashita Sirohi and Simran Agarwal)

PHOTOS BY DINESH KHANNA

The quintessential image of Rajasthan is often one of princely lifestyle and courtly traditions, captured within heritage hotels, and imposing palace/fort museums showcasing royal artefacts. Aside from such opulent displays of regalia and palanquins, the Arna Jharna museum celebrates the quiet beauty of the desert and local adaptation to life in this terrain.

The wide open spaces of the Arna Jharna museum is a reflection of the expansiveness of the desert terrain

Nestled in Moklawas village near Jodhpur, in the midst of desert flora and fauna, Arna Jharna is an expression of the lifelong efforts of Komal Kothari and Vijaydan Detha at providing an alternative image of Rajasthan as a region rich in folk culture and oral traditions. It is a museum dedicated to the Thar as frontier region informed by a history of travel and mobility.

This photo with Komal Kothari was taken soon after he had acquired the ‘perfect spot’ for a desert museum

Kothari, the renowned oral historian, along with Detha, the famed writer of Rajasthani folktales, formed one of the greatest intellectual partnerships of post-Independence India. It was this partnership that found fruition as the Rupayan Sansthan, an institution dedicated to the folklore of Rajasthan, established by Kothari and Detha in 1960–65 (See overview article from the module ‘Reimagining Rajasthan: An Institutional History of Rupayan Sansthan’). Over the years, Rupayan Sansthan has come to have a special association with the performing arts of Rajasthan, which has evolved within the wider framework of cultural engagement refined by Kothari. Rupayan Sansthan manages the Arna Jharna museum, as well as an archive in Jodhpur city consisting of an extensive corpus of audio-video recordings and a small but significant collection of photos from the areas of folklore, performing arts, sustainable living, indigenous knowledge, and arts and crafts. Traditionally, the theme of regional culture is subsumed under the majoritarian concept of the nation state. The archive and the museum, on the other hand, offer a more profound understanding of the unique folk culture and regional identity of Rajasthan by documenting the life, leisure and labour of the people of the desert.

Seen from left to right seated under the tree are the musicians Pappa Khan Manganiar on the dholak, Shankra Khan Manganiar, Hakam Khan Manganiar on the kamaicha in an open-air setting at the museum. Multan Khan Manganiar looks on. In the background are the mud buildings housing one of the museum displays

Collection of Folk Musical Instruments

Built in the local style of village architecture, Arna Jharna evokes the romance of nomadism with open-air music performances by local groups and artistes of the region. It also houses a matchless collection of folk musical instruments unique to western South Asia, including the jantar, jogia sarangi and nagfani, which are no longer used or produced. Rupayan Sansthan is presently raising funds for a research project linking the musical instruments in its collection with musical traditions available as recordings in its audio-video archive. The publication of a catalogue and monograph, as well as the renovation of the folk musical instruments gallery to incorporate the AV experience of associated musical traditions are also envisaged.

.

1a

1b

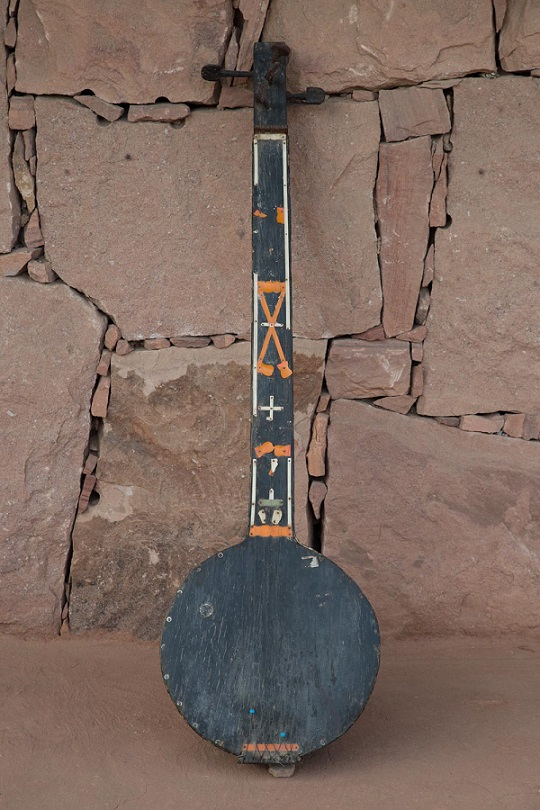

Fig. 1a & b. Sarinda: This bowed chordophone or stringed instrument is used in some form or the other from Iran, and Baluchistan in Pakistan, to north and east India. It is used only by the Surnaiya Langas in western Rajasthan, where it is also known as the surinda, as accompaniment to the aerophonic instruments played by these exclusively instrumentalist musicians. It is made of sheesham wood and has eight strings. Note the intricate patterns decorating these particular instruments.

Sarangi: Different kinds of this bowed chordophone—the sindhi sarangi, pyaledar sarangi, gujratan sarangi, dedhpasli sarangi and jogiya sarangi—are used in different parts of Rajasthan by Langa, Manganiar, Dhadhi and Mewati Jogi musicians. The sarangi produces a specially lilting tune. Note the ghungroos or bells on the bow of this particular jogiya sarangi that would have provided rhythmic accompaniment

Ravanhatha: The long neck in this string instrument lends itself to being held up and played by Nayak or Bhil bhopas or priests as they dance in the Pabuji re phad performances. The sound of the ghungroos attached to the bow are an intrinsic part of the instrument’s music. The resonator is made of coconut shell, and one string of horse-tail hair and one or two of steel stretch across the long neck of the ravanhatha. Importantly, the bhopas themselves manufacture this signature instrument of theirs.

Kamaicha: This bowed chordophone is reflective of the shared history of the western frontier of South Asia, as it is only found in Sindh in Pakistan and western Rajasthan, used exclusively by Manganiar musicians. Komal Kothari traces its origins to Gujarat. It is immediately recognisable by its large, rounded body, covered with goatskin. It is usually carved out of a single block of mango wood and sometimes sheesham. Its two main guts strings are made of goat intestine and three other strings are made of steel. Altogether, it has 17 strings. It is played with a bow known as gaj. The kamaicha is known for its deep, haunting melody.

Hakam Khan Manganiar is seen here tuning the kamaicha.

Ektara: The ektara is a plucked chordophone, commonly used in devotional music in different parts of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The great Bhakti saint of Rajasthan, Meera Bai, used it to sing all her compositions. A single string stretches from a small resonator across a long bamboo neck, which is plucked by a single finger.

Tandura: Also known as the veena or chautra, it is used by the Meghwal, Kamad and Bhil communities in devotional group singing. The tandura can be found all over Rajasthan except in the district of Jalore. The player wears a mijraf on the tip of the index finger, striking the strings with rhythmic stress from right to left.

Aerophones: The wind instruments used in the folk music of Rajasthan are designed so that their music carries in the vast, empty distances of the desert landscape. They are played to produce continuous sound achieved through circular breathing. They can be divided between oboes and flutes

.

Bankia: This aerophonic instrument is used by bhopas and the Dhadhi community. It is played by blowing hard at the mouthpiece, functioning like a simple bugle. It is used during weddings, ceremonial processions, festive occasions, and as an accompanying instrument in folk dances.

Khartal: Classed as an idiophone, the tapping sounds of the khartal are achieved through clicking two pairs of rectangular pieces of smoothened and polished wood held in both hands, one piece with the thumb, the other with the four fingers. It is used in Rajasthan mostly by Manganiar musicians but also by the Langas.

Manjira: A percussion instrument, manjiras are little cymbals commonly used in devotional music in India, known for their sharp clanging sound. Female dancers of the Kamad community hold them in their hands and tie them to their legs in the Teratali folk dance. They ensure that they strike the manjiras even as they balance metal pots on their heads and sometimes hold swords in their mouths.

The Broom Project

The ‘living museum’, through displays such as that of different kinds of brooms and pottery, gives visitors a glimpse into not only the labour and skills of the local communities but also the world of rituals and beliefs associated with these objects of daily life. These humble objects are rooted in the local ecology and traditional knowledge systems of the region. This is the reason Komal Kothari chose the broom, an inconspicuous object of fundamental importance in our lives, as the flagship concept for a museum collection. The broom project was supported by Ford Foundation, India. It was directed by Rustom Bharucha, author of the book on Kothari Rajasthan: An Oral History, presently a professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Bharucha was aided by Kothari’s son, Kuldeep, presently the secretary of Rupayan Sansthan. The display was designed and curated by the visual artist Madan Meena.

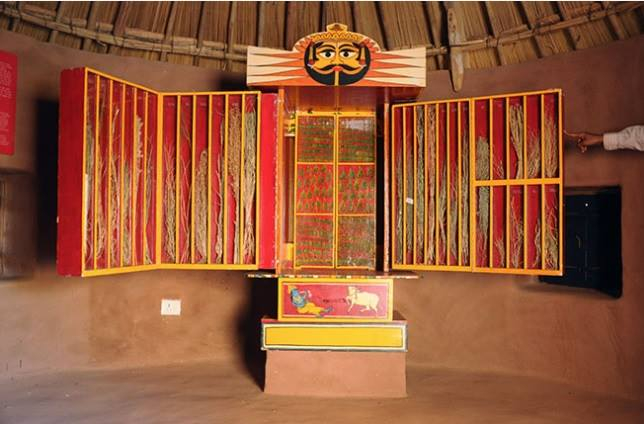

A kavad, a story-telling device, is customised at the Arna Jharna museum to showcase the different varieties of desert grasses. Courtesy Rupayan Sansthan.

The brooms are classified according to the different agrarian zones of Rajasthan identified by Komal Kothari: millet (bajra), sorghum (jowar) and maize. The collection is divided into the ‘female’ brooms used in the inner spaces and the ‘male’ brooms reserved for outer spaces. The names of the brooms can indicate their ‘gender’: examples of female brooms being buari and havarni, and male ones being bungra and havarno. The female brooms are associated with the goddess Lakshmi signifying prosperity and are stored in horizontal position for luck. The male brooms tend to be sturdier to suit the purpose of sweeping rougher surfaces. Types of them are also used during the harvest season to remove husk. Through a series of videos on broom production, the museum aims at sensitising the audience about the stigma and risks associated with it for the largely poor and marginalised communities that produce them for our daily use.

Jhoonjhli. Grass; District: Sirohi; Zone: Maize. The jhoonjhli grass that is used to manufacture this broom grows in the forests and hills of southern Rajasthan. It is collected by the Garasiya and tribal Bhil communities, who sell it to villagers at the rate of rupee one for a bundle. Although this broom is used both inside and outside, albeit only on mud floor surfaces, it has a feminine name. Broom made by Amru Khan.

Khemep. Shrub; District: Barmer; Zone: Millet. Found on the scrublands and sand dunes of western Rajasthan, this shrub is adapted to various domestic uses. It is made into a broom used to sweep the insides of homes as well as cattle sheds. It is used to manufacture a rope that is tied to pots to draw water from wells and twisted into rings used by women to balance water pots on their heads. Its fruits are used to make a vegetable dish. Villagers use it to manufacture a home remedy for skin diseases. Broom by made Ranaram Rebari.

Siniya. Grass; District: Jodhpur; Zone: Millet. This small grass grows in arid zones. It is used to clean cattle pens. Broom made by Kirtaram Chaudhary.

Daab. Grass; District: Jalore; Zone: Millet. This grass lends itself to numerous ritual as well as practical uses. It is used in rituals pertaining to death, to sprinkle and offer water, made into a ring and worn by the son conducting the rituals. It is also used to ward off eclipses. The grass is used to make brushes for whitewashing homes and ropes for making cots. Its fragrant roots are used in perfumery. Broom made by Babu Lal.

Panni. Grass; District: Dausa; Zone: Millet. The grass grows in loose soil during the monsoon and is cut during the Kartik month of the Hindu calendar, corresponding with October–November. This broom is manufactured by sweepers and used by them to clean public spaces. Broom made by Ratan Lal.

Burada re bangri. Grass; District: Barmer; Zone: Millet. Broom made by Shakaram Meghwal.

Kankoon ro bhuaro. Plant; District: Alwar; Zone: Millet. This shrub grows in the Sariska forest belt throughout the year. The broom is used in cattle sheds. Broom made by Laxman Meena.

Guncho khejur. The dried branches of the date palm tree supply readymade brooms that are used for the highly specialised task of removing cobwebs! It is made by the Bhil community and other tribal communities.

This pool of water next to the museum is known as Raimal Talab or Nada. It is contained by a bund in a traditional rainwater-harvest system. Local legend has it that it was built in partnership by a brother, Mal, who owned the land, and his sister, Rai, who financed its construction. Sadly, the siblings fell out spectacularly when both demanded that it is named after him/her leading to both their deaths. The embittered Rai put a curse on it that led to it being dry for centuries. It is an auspicious sign that the pool has been full since the museum was established, providing a watering hole for animals and birds

References

Bharucha, Rustom, 2003. Oral History of Rajasthan: Conversations with Komal Kothari. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Kothari, Komal. 1972. Monograph on Langas: A Folk Musician Caste of Rajasthan. Jodhpur: Rupayan Sansthan.

Neuman, Daniel, Shubha Chaudhuri with Komal Kothari. 2006. Bards, Ballads and Boundaries: An Ethnographic Atlas of Music Traditions in Western Rajasthan. Calcutta, London and New York: Seagull Books.