This article is based on conversations with Dinesh Yadav, a theatre director and artist who has been working with and on Pandun ka kada (Pandava’s couplets) since 1997, and Gafruddin Mewati Jogi, a senior artist and performer of Pandun ka kada.

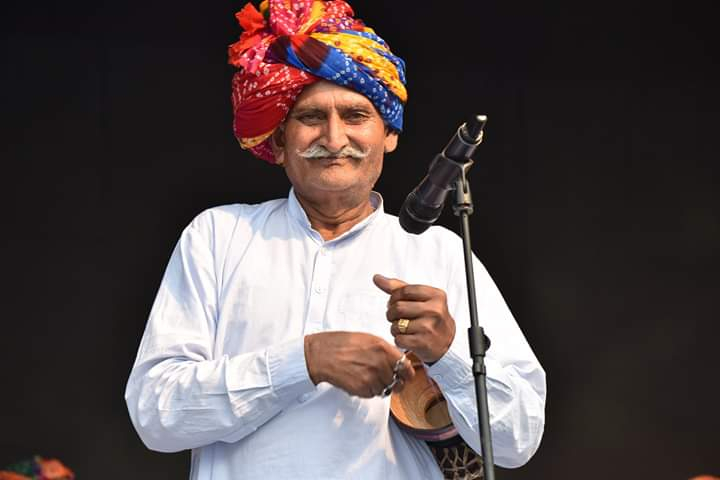

For centuries, Mahabharata has allowed for fascinating variations of itself. Pandun ka kada (Pandava’s couplets) is one such variation. In this tradition of singing and storytelling, artists first recite a doha (couplet), and then sing primarily in dhani raga as they elaborate on it. (Fig. 1)

A little-known tradition, Pandun ka kada, comprising over 2,500 dohas, is sung by the Jogi and Meo communities of Mewat. There are no formal boundaries demarcating the Mewat region and, mapped roughly, it includes Faridabad, Nuh and Mewat in Haryana, and Alwar and Bharatpur districts in Rajasthan. Mewati, the dialect of the region and the language in which Pandun ka kada is recited and sung, is influenced by both Haryanvi and Rajasthani. (Fig. 2)

Like many storytelling traditions of north India, Pandun ka kada was performed wherever there was a gathering of people. Artists would travel from village to village, performing between clusters of houses, in village squares, at weddings as entertainment for the baraat (wedding procession) at chhuchhak (a postnatal ceremony), and so on, and collected grains and other basic supplies as payment. An oral tradition, Pandun ka kada has been passed down from generation to generation from memory. While there is little to no historical material available on this tradition, it is speculated that poet Sadullah Khan put Pandun ka kada to paper for the first time in the middle of the sixteenth century, though there are no known records or remains of the manuscript.

Gafruddin Mewati Jogi, an elderly artist who follows his traditional occupation of performing Pandun ka kada, learnt the entire performance from his father and guru Buddhha Singh Jogi Mewati. (Fig. 3) Until just a few decades ago, Pandun ka kada was quite popular, and it was not uncommon for people wanting to have a performance of these dohas at family weddings to fix the wedding dates, according to when Buddha Singh was available to perform. In those days, Gafruddin remembers performing for as many as three baraats in a single day or night. (Fig. 4) Pandun ka kada was very much a part of local culture and parlance, and often people at panchayats would quote dohas from the tradition to aid in the process of decision-making and conflict resolution, which indicates at something which Gafruddin explicitly states as well—people would listen to Pandun ka kada and find doing so important because, to paraphrase Gafruddin, there is something to learn from these dohas: 'usmein wazan hai, gyaan hai' (It has weight and wisdom).

A Unique Tradition

One of the most fascinating and fundamental aspects of the Mahabharata is that there is no notion of an original. Different regions, languages and communities in India have their own tradition(s) of retelling the story, and thus, like all the traditions of Mahabharata, Pandun ka kada is unique.

The Nath Jogis of Gorakhpur are followers of Guru Gorakhnath, and Pandun ka kada is influenced by the Gorakhnath tradition of Gorakhpur, a city which takes its name from its revered guru. In fact, the story as retold in Pandun ka kada begins with an exchange between Guru Gorakhnath and his disciples. The disciples come to Guru Gorakhnath and express their desire to see duniyaadari (which can be roughly translated to worldly life), saying that they have experienced sanyaas (renunciation of worldly affairs), and want to see worldly life. Guru Gorakhnath acquiesces, and in order to show his disciples the worldly life they wish to witness, he takes them to Hastinapur. From there Mahabharata unfolds, and the story is seen from the bird’s-eye view of Guru Gorakhnath.

In most versions of the Mahabharata it is episodes such as Draupadi cheer haran (forceful stripping or taking away of clothes) which form the major cause of animosity between the Kauravas and Pandavas. In Pandun ka kada, the rivalry begins with another episode altogether.

Gandhari and Kunti both do puja to Suryadev (Sun God). One day Gandhari asks Duryodhana to build a large mud elephant for her, and from atop that elephant, she begins doing her puja. Seeing this, Kunti taunts Arjun:

Arjun mera ladla,

na to in batan ko tol,

ek haathi mohe mangayi de,

teri diyo mausi ne bol

Arjuna my son,

mark the weight of my words,

your mausi [maternal aunt] has taunted me that all my sons are useless,

and that her son Duryodhana has made her a tall elephant.

Arjun mulls this over and decides that he cannot make a large mud elephant, and hence must do something else. So, with his lakshya-dhaari baan (arrow sure to reach its mark), he sends a letter to his father, Indra, asking for Airavata (a white elephant who is Indra’s vehicle). As soon as Indra receives his son’s letter, he immediately sends Airavata to Arjuna on the same lakshya-dhaari baan. Now, Kunti climbs atop Airavata to do her puja to Suryadev, and of course, Airavata is much larger than even the large mud elephant Duryodhana made for Gandhari.

When Kunti’s puja is over, Bheema, who is a manchala (unafraid with a streak of mischief) character from the beginning of the story, goes up to Arjuna and suggests that before sending Airavata back to Indra, he, Bheema, could sit atop Airavata and take it to the Jamuna River to bathe. Arjun agrees, and Bheema sits atop Airavata. On his way to the river, Bheema, sitting atop the mighty Airavata, breaks the mud elephant Duryodhana built for Gandhari. Gandhari is enraged and taunts Duryodhana:

tero maati ka haathi banaeyo,

woh bhi diyo dhakel,

jinka bhai markhana,

unko dunia mein haasi khel

Even the mud elephant you made for me was broken,

life will be a laugh for those whose brother is a mischief monger.

And from here begins the rivalry between the Pandavas and Kauravas. Pandun ka kada has several similar deviations from the ‘mainstream’ Mahabharata and, like many retellings, its episodes often break away and then eventually return to the popular and prevalent storyline.

The Jogis and Meos of Mewat

The Jogis and Meos of Mewat, who sing Pandun ka kada, are unique communities. In some traditions they consider themselves Jogis, while in others they consider themselves Muslims. Apart from the Mahabharata, their songs retell stories about Shiva and other Hindu devas, and for several centuries their culture has been a blend of Hindu and Muslim practices. The Meos in particular are said to be Rajput Hindus who converted to Islam during the time of Aurangzeb. Drawing on Pandun ka kada, Meos have traditionally traced their lineage to characters from Mahabharata, such as Arjuna.

Most contemporary work on Meos states that their cultural practices and self-image are increasingly shaped by the mainstream discourse of Sunni Islam. As a result, the mixed practices of Meo culture have faded, especially in the last 50 years. However, traditionally, while Meos followed three Muslim practices—nikah (Muslim marriage ceremony), khatna (circumcision), and burying the deceased—Jogis and Meos celebrated several Hindu festivals, were followers of Guru Gorakhnath, and had their own temples of Hindu devas and devis. While this is by no means a unique phenomenon, given India’s rich culture and complexity of interaction between communities and traditions, the Jogis and Meos are remarkable in that their culture and their own relationship to their ‘identity’ as Jogis and Meos and as Hindus and Muslims present us with an avenue to take note of and reflect upon Indian culture. It becomes a context within which we can ask: What can the existence of communities such as Meos and Jogis tell us about Indian culture and its attitude towards religion, ‘identity’, communities, and traditions?

This is an important question to raise today, when clear lines are being drawn in Indian society—lines that tend to ignore the reality of India as presented by the Jogis and Meos. To put it more clearly, it is important to think about what the Jogis and Meos and their tradition of Pandun ka kada can tell us about Indian culture in a time when it is very possible for these communities to be asked: ‘why should we sing these stories, they are not our stories?’ or for these communities to be told: ‘why are you singing these stories, these are not your stories, they are ours’.

Pandun ka kada in Contemporary Times

Once a thriving art form in Mewat, Pandun ka kada is no longer popular. In decline for some time, the tradition has lost most of its audiences and practitioners. Performances would traditionally take place through the night, but only a few today choose to sit through such extended retellings. The number of artists performing Pandun ka kada has also shrunk, and today there are only two or three artists who continue to sing this retelling of Mahabharata. Of these, Gafruddin Mewati Jogi is the only person who has all 2,500 and more couplets committed to memory. For those who would like to locate these artists and witness a performance, Kaman and Deeg tehsils in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, and Mewat district in Haryana are places to explore.

There is a vital link between folk traditions and artist/performing communities. As the traditional performers of Pandun ka kada, Jogis and Meos are also its only performers and principal guardians. For reasons yet to be fully determined and reflected upon, the vital link between Pandun ka kada and Jogis and Meos is tenuous today. In the recent past, few within these communities have picked up the tradition as their own. Artists such as Gafruddin, who do continue to sing Pandun ka kada, rely on debt and occasional international performances to make ends meet.

Jogiyaar Mahabharata, a production by Swayambhu Foundation New Delhi, is an attempt to bring Pandun ka kada to a national audience in order to revitalise the tradition and create a new platform for these artists. (Fig. 5) Dr Dinesh Yadav, creator and director of Jogiyaar Mahabharata, also hopes to undertake projects that create an environment in which Jogis and Meos can reclaim Pandun ka kada as their tradition, and through which the vital link between these communities and their tradition can be re-strengthened.

Bibliography

Chawla, Abhay. ‘How Meos Shape Their Identity.’ Economic and Political Weekly 51, no. 10 (March 5, 2016): 7–8.

Ghosh, Paramita. ‘What You Should Know about the Meo Muslims of Mewat.’ Hindustan Times, September 16, 2016. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.hindustantimes.com/static/Meo-Muslims-of-Mewat/.

Mayaram, Shail. ‘Meos of Mewat: Synthesising Hindu-Muslim Identities.’ Manushi, no. 103 (1998): 5–10.

———. Resisting Regimes: Myth, Memory, and the Shaping of a Muslim Identity. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Naqvi, Saba. ‘Meet the Muslims Who Consider Themselves Descendants of Arjuna’. Scroll.in, March 30, 2016. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://scroll.in/article/805833/meet-the-muslims-who-consider-themselves-descendants-of-arjuna.

Roychowdhury, Adrija. ‘Meet the Meos, the Muslim “Gau Rakhshaks” of Mewat.’ The Indian Express, New Delhi, June 13, 2017. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/cow-vigilantes-groups-cow-slaughter-meet-the-meos-the-muslim-gau-rakhshaks-of-mewat-4700295/.

Co-contributers:

Dr Dinesh Yadav is a graduate from NSD and LAMDA and has been involved in the theatre world for more than fifteen years. A doctorate in Chemistry (2008) and Theatre (2017), Dr Yadav has worked in various capacities in the media, theatre and film industries. In 1997 after a chance meeting with Gafaruddin Mewati, a Jogi following his traditional occupation of rendering Pandun ka kada, Dr Yadav became fascinated by this Mewati tradition of singing the Mahabharata. He has been involved in documenting, reviving and showcasing Pandun ka kada ever since. His organisation, Swayambhu Foundation, is actively involved in fulfilling this goal. Swayambhu Foundation's production, “Jogiyaar Mahabharata”, is an outcome of and one step towards this larger effort.

Shri Gafruddin Mewati Jogi is a renowned folk artist, Bhapangvaadak, and performer of Pandun ka kada. He began singing Pandun ka kada with his father, Shri Buddha Singh Jogi, at the age of seven. Gafruddin ji has been performing Pandun ka kada for more than 60 years now and is currently the only person alive who knows all 2,500 and more couplets of Pandun ka kada. He is based in Bharatpur district, Rajasthan, and can be reached on +919829567606.