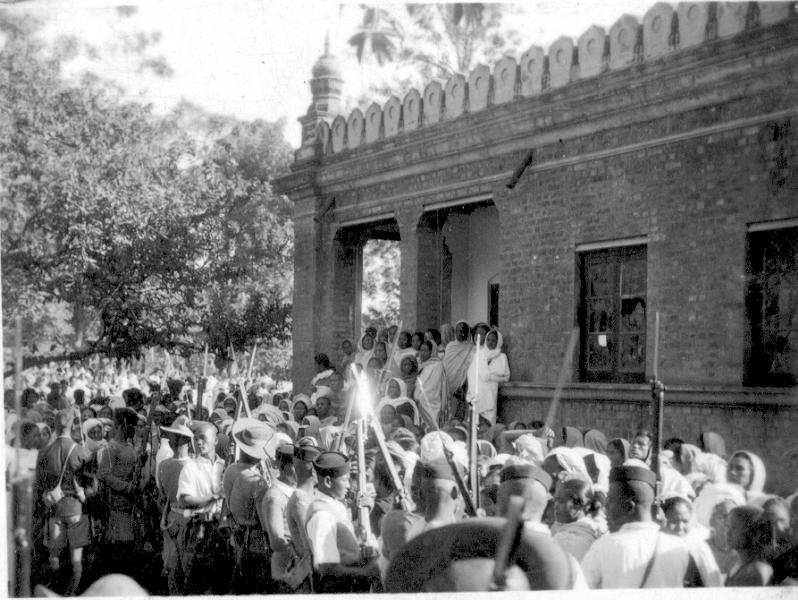

Long before the images of women of Shaheen Bagh came to symbolise feminine power in contemporary India, thousands of Manipuri women came together to effect change unlike any other. We look at how the two Nupi Lan movements (1904 and 1939) changed the course of history. (In pic: The Nupi Lan Memorial in Imphal, Manipur; Photo courtesy: Shruti Chakraborty)

In a letter to confidant and fellow activist Ludwig Kugelmann on December 12, 1868, Karl Marx wrote: ‘Anybody who knows anything of history knows that great social changes are impossible without the feminine ferment.’ Little did he know that almost a century later, the very day would be commemorated as ‘Nupi Lan Day’ in the state of Manipur, India. Nupi Lan means Women’s War, and December 12 marks the day when thousands of women in Manipur valiantly stood up for the rights of their countrymen and women against the British in 1939.

In the year 2020, as the women of Shaheen Bagh make headlines across the world, creating history, there is some merit in looking back at one of the first protests led by women back in 1904. Those familiar with the history of Manipur, know that Manipuri women have always enjoyed a high and free position in the kingdom. It is believed the Khwairamband Bazar (currently more popularly known as Ima Keithel, or Mother’s Market) was set up in the late sixteenth century, and more than 2000 women have been conducting trade of all kinds of commodities here ever since. This market proved to be an important location for the two Nupi Lans later.

The Nupi Lan of 1904

The first agitation was triggered by the action of Colonel Maxwell in July 1904 to reintroduce the abolished Lallup System (wherein men were required to perform free labour for 10 days after every 30 days). After the bungalows of two British officials was burnt down in 1904, Maxwell temporarily reintroduced the Lallup System to rebuild them. This move proved a misstep as the women rose up in unison to protest against the injustice of forced labour.[1]

Related | History of Student Protests in Postcolonial India

On September 3, thousands of women gathered spontaneously and marched towards Maxwell’s official residence. They were assured that the order would be reconsidered, however, it all came to naught. Hence, on October 5, around 5000 women gathered at Khwairamband Bazar in protest, refusing to move till the order was retracted. ‘The violent agitations and demonstrations led by the market women had to be dispersed by the use of force but ultimately the British had to build the houses at their own expense,’ wrote Sanamani Yambem in the Economic and Political Weekly.[2] The womenfolk of Imphal, thus, according to academic Lal Dena, achieved what their male folk could not.[3]

In 1925, the women raised their voice again when the state authorities increased the water tax. There were widespread demonstrations, again led by the tradeswomen, against the measure. This was similar to the later women’s agitation later of 1939.[4]

Second Nupi Lan in 1939

After the Anglo-Manipur War of 1891, Manipur came under direct British rule till 1907, when the administration was handed over to Raja Churachand Singh and his durbar. However, a British Political Agent was employed to oversee the functioning of the region and had powers over the royal durbar. This had major implications on the economy and trade of Manipur.

The Manipur valley was and is a major rice-growing region. While rice was exported outside of Manipur—primarily Assam—even before 1891, the quantity increased by gargantuan proportions thereafter. Irrespective of production and internal need, export quantity continued to increase. This was aided by the replacement of bullock carts as mode of transport by motorised vehicles, which made it easier and faster to export large quantities of rice. According to Prof. N. Joykumar, from 1925–26 to 1938, there was an increase of only 10,322 acres of total area under cultivation, however the volume of the export of rice increased from 1,55,014 mounds to 3,72,174 mounds, respectively, before the outbreak of Nupi Lan.[5]

Also read | The Vaishnava Temples of Manipur: An Historical Study

In addition to exporting more rice than Manipur could afford, the British slowly and steadily converted the region into a market for imported manufactured goods, which ultimately led to the decline of indigenous cottage industries.[6] For instance, the import of Liverpool Salt (which was sold cheaply) competed with the local brine wells of the state. On the other hand, the Marwaris—who had settled in the region and took over much of the rice trade—spied a business opportunity and bought most of the paddy land, and built rice mills. This resulted in running the local husking industry out of business.

All these factors contributed to the mobilisation of the second Nupi Lan. In July-August and then November 1939, excessive rain and hail severely damaged paddy production. The farmers appealed to the durbar to ban export to meet local demand. While the durbar temporarily agreed, they overturned the ban under pressure from the exporters. The situation resulted in acute shortage of rice and a rise in price, hitting the poor sections of Manipur hard.

Also read | Laiphadibi: The Cloth Dolls that Guard and Guide Manipuri People

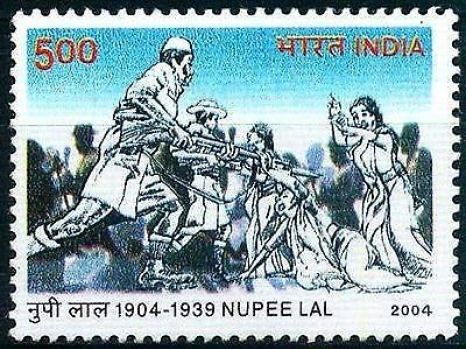

On December 12, hundreds of women came out on the streets of Imphal demanding a ban on rice export and a closure of rice mills, marching up to the durbar office. However, since Maharaja Churachand Singh was travelling, they were told a decision could not be taken. Undeterred, the women dragged T.A. Sharpe, president of the Manipur state durbar, to the Telegraph office to send an urgent telegram to the maharaja. Sharpe and other officials were held captive till a response came, with the gathering of women swelling to around 4000. Soon a posse of Assam rifles arrived at the scene to disperse the women, and a ruthless bayonet charge followed. It was met with stone-pelting by the women, many of whom were injured.[7] This scene has been portrayed in the Nupi Lan Memorial in Imphal. While the women had to backtrack under the shower of brutality, their voices were heard by the maharaja, who messaged the next day asking for rice export to be stopped. Jubilant, the women then turned their focus towards the rice mills, eliciting a promise from them to stop milling paddy. Minor attempts by traders to restart export or milling was met with immediate resistance by the women.

Khwairamband Bazar was closed for almost a year in protest against the violence meted out to the women. As Yambem wrote, ‘The Nupi Lan, which started as an agitation by Manipuri women against the economic policies of the Maharaja and the Marwari monopolists, later on changed its character to become a movement for constitutional and administrative reform in Manipur.’[8]

Since then, Manipuri women have bravely led protests across the years—be it the Meira Paibi movement in the 1970s against drug abuse and alcoholism or the 12 women standing nude in 2004 against AFSPA. There have been other women-led movements across the country as well, but Nupi Lan remains a strong testament to the power of women’s voice in India.

This article was also published in Scroll.in.

Notes

[1] ‘Nupi Lan: The Great Second Women Agitation of Manipur, 1939-40 - Part 1’, E-pao.net, accessed March 5, 2020, http://e-pao.net/epSubPageExtractor.asp?src=manipur.History_of_Manipur.Nupi_Lan.Nupi_Lan_The_Great_Second_Women_Agitation_of_Manipur_1939-40_Part_1.

[2] Sanamani Yambem in the EPW 1976 article ‘Nupi Lan Manipur Women s Agitation, 1939’, accessed March 5, 2020, https://www.epw.in/journal/1976/8/special-articles/nupi-lan-manipur-women-s-agitation-1939.html.

[3] Nupi Lan : The Great Second Women Agitation of Manipur, 1939-40 - Part 1’, E-pao.net, accessed March 5, 2020, http://e-pao.net/epSubPageExtractor.asp?src=manipur.History_of_Manipur.Nupi_Lan.Nupi_Lan_The_Great_Second_Women_Agitation_of_Manipur_1939-40_Part_1.

[4] Sanamani Yambem in the EPW 1976 article ‘Nupi Lan Manipur Women s Agitation, 1939’, accessed March 5, 2020, https://www.epw.in/journal/1976/8/special-articles/nupi-lan-manipur-women-s-agitation-1939.html

[5] Lal Dena (ed.), History of Modem Manipur, 1826-1949 (New Delhi: Omsons, 1991), 146.

[6] Nupi Lan: The Great Second Women Agitation of Manipur, 1939-40 - Part 2’, E-pao.net, accessed March 5, 2020, http://www.e-pao.net/epSubPageExtractor.asp?src=manipur.History_of_Manipur.Nupi_Lan.Nupi_Lan_The_Great_Second_Women_Agitation_of_Manipur_1939-40_Part_2.

[7] Haorongbam Sudhirkumar Singh, ‘Socio religious and political movements in modern Manipur 1934–51’, Chapter 4, 2011, accessed March 5, 2020, https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/121665/9/09_chapter%204.pdf

[8] Sanamani Yambem in the EPW 1976 article ‘Nupi Lan Manipur Women s Agitation, 1939’, accessed March 5, 2020, https://www.epw.in/journal/1976/8/special-articles/nupi-lan-manipur-women-s-agitation-1939.html.