The state of Jharkhand is part of the central tribal belt of India and home to more than 40 Adivasi communities such as Munda, Oraon, Ho, Santal, Birhor and Kharia. The habitations of these communities typically comprise mud houses located within paddy fields and forests. Driving along the highway and turning into one of the smaller roads, one is likely to find clusters of neatly plastered and painted mud houses flanking the street. In the months between October and January particularly, the houses are resplendent, having been freshly painted by the village women in preparation for the harvest festival of Sohrai. This is considered as an auspicious time, when the painting of the houses forms part of the ritual renewal of the dwelling and marks the end of one agricultural cycle and the beginning of another. The painting of murals on the occasion of Sohrai has led to its nomenclature as Sohrai art. It is also a common practice for women among some rural communities to paint murals in preparation for weddings. Such paintings are known as Khovar, where kho refers to cave or shelter and var refers to the bridal couple. The word thus refers to the mural art of the bridal room. Both Sohrai and Khovar however are not singular traditions but broad terms encompassing a range of mural practices and designs characteristic of Jharkhand. This article focuses on two regions, Hazaribagh in the north and Singhbhum in the south, and discusses the production, design scheme and motifs, and the significance of the mural art in each site.

Figs. 1 and 2. Murals of Jharkhand

Before delving into a detailed discussion of design, it is important to understand the role of murals in the preservation of mud architecture. Mud is one of the oldest building materials and is extensively used by communities around the world. Contrary to popular belief, mud buildings can be extremely strong structures that last for centuries. This however requires regular maintenance in the form of plastering and painting in order for the mud structures to weather rains and moisture. Jharkhand has heavy monsoons and the mud houses of the region are repaired and re-plastered after the rainy season. The preparations begin with the reworking of the wall surface. Depending on the extent of weathering or rain-damage, fresh clay is added to cover the cracks or other damaged parts. The entire wall is then scrubbed to remove the earlier mural or a new layer of clay or cow dung is added over the existing wall surface. Once this dries, the design is drawn using a piece of chalk, or inscribed into the wall using a sharp object like a nail. Natural clay oxides that will be used for painting are prepared with water and then applied according to the design. The tools and techniques used for painting vary from region to region and across communities. The differences notwithstanding, the final mural produces a smooth surface that works to largely repel water or at least ensure that it flows down and does not penetrate and weaken the earthen wall. In this way, the practice of painting murals becomes integral to the preservation of the mud houses.

Fig. 3. Clay plaster in preparation for painting a mural; note the white lines which are remnants of the previous mural

Mural techniques

The mural traditions in Jharkhand present a variegated landscape of techniques and motifs. Broadly, mural designs are distinctly different in Singhbhum and Hazaribagh. The types of clays found in the two regions differ in mineral content and therefore in pigmentation, leading to two distinctive colour palettes. Singhbhum has brighter colour clays occurring naturally in the region, and the murals tend to have deep rust, ochre, black and light blue colours. Hazaribagh on the other hand has less variation and the mural designs are dominated by black manganese-rich clay, the nearly white kaolin clay and the occasional use of reddish coloured clays. The difference in palette is further heightened by the use of artificial paints, which is much more common in Singhbhum than in Hazaribagh. Singhbhum is historically a more highly industrialised region and Adivasi and non-Adivasi villagers have been employed by local industrial establishments for generations. The proximity to industrial construction techniques may have resulted in the exposure to artificial paints and brushes, which in turn led to its incorporation into domestic mural practices. On account of this as well, the mural palette of Singhbhum is brighter than that in the Hazaribagh region.

The motifs found in Singhbhum murals tend to be geometric and characterised by very precise painting. While horizontal bands form the basic structure of the murals, some women add geometric shapes or floral motifs by way of detail. The Hazaribagh murals are completely different and present more organic forms. Each mural is a profusion of lines, dots, animal figures and plants, often representing religious iconography such as the mythic tree of life or Pashupati (a horned image of Lord Shiva as the lord of animals, see Fig. 7). These are discussed in greater detail in the accompanying archive of mural designs.

There are two techniques used to produce the murals viz. comb-cutting and painting. Comb-cutting is an unusual technique used by mostly by Kurmi women in the few villages around Hazaribagh. A layer of black or dark grey manganese-rich clay is first applied on the wall. Once it dries, a second layer of whitish kaolin clay is applied. When the second layer is just set but not fully dry, the designs are scraped onto the wall using a broken comb or a similar toothed instrument. This scratches off the kaolin clay to reveal the blackened surface below. The final designs thus comprise multiple delicate black lines on a whitened surface.

Fig. 4. Mural produced with comb-cutting technique

Fig. 5. Detail showing scraping gesture revealing the black clay below the white surface

Painting is the more common technique used in mural production. However, due to the variation in tools, the mural designs in different villages and by different communities are quite varied as well. The most basic painting device is a piece of cloth which is dipped in colour and then applied to the wall resulting in large swathes of colour. This technique of painting is common in the Singhbhum region and the basic design scheme comprises broad horizontal bands starting at the base of the wall and extending to the top. It is likely that the strong horizontality of the mural aesthetic is linked to the technique of painting itself.

Fig. 6. Typical Singhbhum mud houses painted in horizontal bands

Fig. 7. Hazaribagh Kurmi sohrai painted using datun or chewed neem twig

In the Hazaribagh region, the painting technique is different. Women use datun or pieces of twig from the neem tree which are chewed for use as a toothbrush. The frayed and softened edge of the chewed twig becomes a paintbrush, which allows the artist to produce lines and dots on the walls. Consequently, the designs produced with the datun are finer in texture than the large bands of colour characteristic of Singhbhum murals. A third type of mural painting uses the stencil technique, where darker coloured clays are applied in a manner that leaves certain parts of the whitened wall base exposed thus creating a motif (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Hazaribagh ghatwal painting using stencil technique

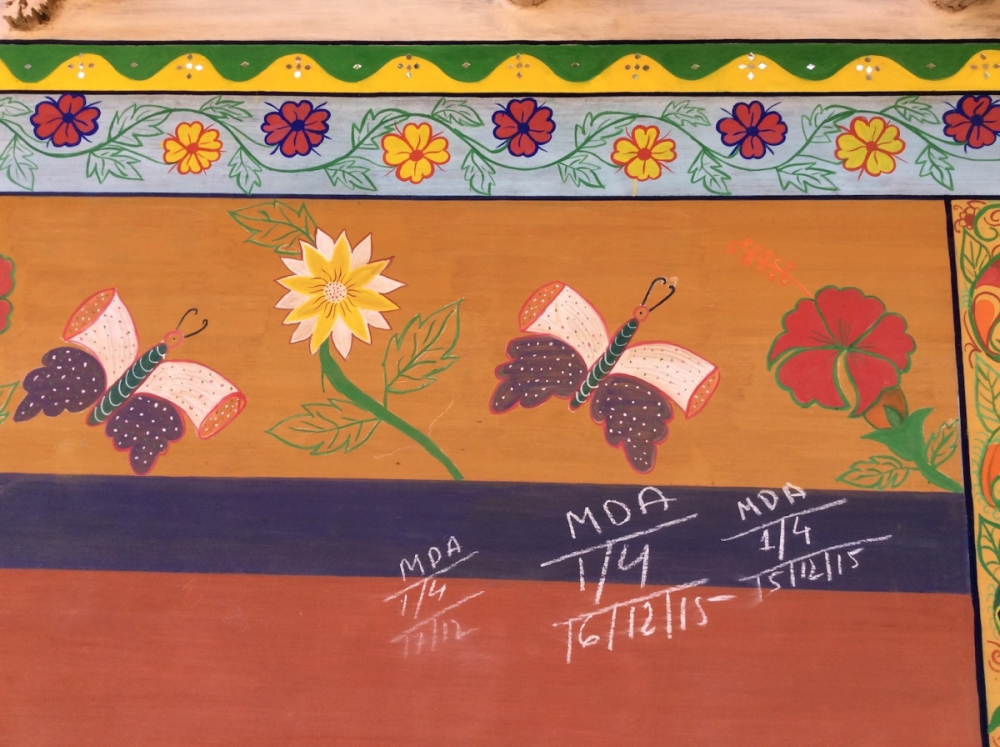

It is important to flag up that not all Singhbhum murals lack detail. The recent addition of paintbrushes to the repertoire of the women artists has led to the emergence of very finely detailed designs in some villages. Women draw elaborate floral patterns, insects, butterflies and decorative details within the horizontal bands painted onto the walls. This, however, is not widespread but is only occasionally found in some villages. Its almost ad hoc occurrence may be attributed to the varying exposure of the women artists, which in turn is directly linked to women’s livelihood and networks of mobility. As mentioned earlier, when women work on construction sites as wage labourers, they encounter the use of paintbrushes and artificial colour more frequently than their agriculturist counterparts. These women then have the opportunity to incorporate the use of brushes into the painting of their murals.

Fig. 9. Mural details using paintbrush in Singhbhum

The inspiration for mural designs is directly linked to women’s networks of mobility since they are the primary artists and men are rarely involved except occasionally for buying coloured clays or paints. For instance, Santal women’s movements are typically limited to their own neighbourhood in the village. This is because the community has a deep-rooted belief in witchcraft and the power of women to cast an evil eye on others. As such, women’s movements are restricted to their own homes and the immediate neighbourhood. Under these circumstances, one of the most important sources of inspiration for the women artists are their neighbours. This is evident in the similarities between mural designs within each village. Over two or three years and cycles of painting, similarities in murals within a village emerge as women see each other’s murals and choose to emulate certain ideas. For instance, a few years back, one of the women in a village decorated her mural with small mirrors, and over the next two years, mirrors became common to mural designs across the village. These channels of inspiration also result in mural designs in even neighbouring villages being distinctly different, since women do not usually visit other villages except for their maternal homes. Increasingly, economic compulsions require women to travel outside the village in search of work, and their movements expand to include transportation networks, places of work visited as daily wagers, the weekly markets in the vicinity of the village. One cannot easily pin down the inspirations from these sites but further research may reveal the impact of popular culture motifs on the women’s mural practices.

Developments and challenges

One of the biggest challenges faced by the women artists are the compulsions of time. The completion of a mural may take between one week and one month (in addition to the preparatory effort of procuring coloured clays), depending on the complexity of design. The women artists typically balance their domestic and agricultural responsibilities with the task of painting. The hours of the morning are taken up by tending to cattle, cleaning the house, gathering wood for fire, and food preparation. It is after lunch and just prior to the return of cattle from grazing at dusk that women typically find the time to paint the walls. This window of opportunity is further narrowed when women work as daily wage labourers since they themselves return home at dusk. In such cases, women attempt to paint the walls little by little in the fading evening light, or often, do not paint at all. The weather affects the schedule of painting as well. Women have to wait for the end of the monsoons in order to begin painting. Bearing in mind the constraints of time and the weather (in terms of the end of the monsoons), women may begin preparations for painting the murals upto one month in advance. The year this study was carried out (2017) saw a protracted monsoon which, unusually, carried on until early November. The window for painting murals thus coincided with the time for harvesting paddy. In short, the production of painting and the elaborateness of designs is directly linked to quantum of domestic responsibilities and the time available to the women artists.

In the Hazaribagh region, the past decade has seen a gradual decline in the production of murals. The challenges faced by the women artists are manifold. On account of the time constraints described above, women increasingly struggle to find the motivation to paint murals. Combined with the gradual decline in mud construction—contributed to in part by state-sponsored rural housing schemes that mandate construction in brick and concrete—this means mud murals are a severely threatened tradition. Jharkhand antiquarian and art expert Bulu Imam and his family started an organisation known as the Tribal Women Artists Cooperative in 1995 to find ways of revitalising the tradition. They created channels for increasing visibility for the women artists through collaborative exhibitions world-wide and by developing techniques for transferring the mural designs onto paper. This has provided the mural art practices with new currency and longevity. Bulu Imam’s son, Justin Imam and his wife Alka, then established the Virasat Foundation which encourages women to continue to paint murals on the walls of their houses. In addition to the paper-based paintings, if the mural traditions are to continue, it is crucial that they remain embedded within the architectural, social, religious and ecological lives of the village communities. The challenges faced by the women artists reveal that the mud murals are not just painted surfaces but a complex and rather fragile ecology of practice.

Further Reading

Bharat, Gauri. 2015. ‘An Enquiry into Santal Wall Painting Practices in Singhbhum, India’, Journal of Adivasi and Indigenous Studies 2.1:35–50. Online) at http://joais.org/papers/vol2no1/3.%20Gauri%20Bharat%2035-50.pdf (viewed on April 2, 2018).

Dallapiccola, Anna L., ed. 2011. Indian Painting: The Lesser Traditions. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Huyler, Stephen. 1994. Painted Prayers: Women’s Art in Village India. London: Thames and Hudson.

Imam, Bulu. 2009. ‘Kovar and Sohrai Art: The Painted Houses of Hazaribagh’ in Heritage India 1.4.

———. 2017. ‘Karanpura must Live: The Story of a Campaign to Save a Landscape” in Sanctuary Asia 37.8. Online at http://www.sanctuaryasia.com/campaigns/10690-karanpura-must-live-the-story-of-a-campaign-to-save-a-landscape.html (viewed on April 2, 2018).

Rycroft, Daniel. 1996. ‘Born From the Soil: The Indigenous Mural Aesthetic of Kheroals in Jharkhand, India’, South Asian Studies 12.1:67–81.

Troisi, Joseph. 1978. Tribal Religion: Religious Belief and Practices Among Santals. New Delhi: Manohar Publications.