Assam has a long tradition of mask making. Although bamboo is usually the raw material of choice, wooden masks have been used for centuries by communities in lower Assam and are still common in khuliya bhaona[1] of Darrang district and bhari gan[2] of the Rabha community. (Fig. 1)

Masks are intrinsic to the Sattriya arts of the state, which flourished as part of the Srimanta Sankardeva-led Bhakti movement (also called Neo-Vaishnavism) in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[3]

Sankardeva, considered the first khanikar (mask maker) in the Sattriya tradition, began the theatrical performance of bhaona at the naamghars (community prayer halls) to instill the ideology of Vaishnavism among the masses of a stratified society. He introduced mukha (mask) in ankiya naats (one-act plays of bhaona) as a key component to capture various expressions of mythical superhuman characters. Mukhas are an important part of bhaona, animating the performances while imparting moral and religious teachings to the viewers.

Sankardeva’s plays, based on stories from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Bhagavata Purana, were imbued with local flavour. His extraordinary creativity and strategy drew people’s attention and opened the path towards a cohesive Sattriya culture. Sankardeva was influenced by the prevalent mask-making tradition in Assam and the rest of India. He improvised on the techniques of the craft that he observed during his visits to various holy places in the country.

As mentioned in Ramcharan Thakur’s Guru Charita[4], Sankardeva began using masks with his debut play Cihna Yatra in 1468.[5] He crafted the masks of Brahma, Garuda and Hara for this play. This tradition was continued by his disciples like Dwaitari Thakur, who used masks in his plays including Nrisimha Yatra.

Aesthetics

The term bhaona is derived from the Sanskrit word 'bhavna', meaning emotion. Masks used in bhaonas express the navarasa (nine poetic emotions) that are impossible for bhaoriyas (actors) to express with bare faces.

Masks such as those of Narasimha (literally, man-lion; an incarnation of Lord Vishnu) and Ravana (from the Ramayana) are viewed with awe and reverence because of their grandeur as well as their powerful characterisation in the myths.

Traditionally, masks are kept in the naamghar. Earthen lamps and incense sticks are lit in front of them. Because of the belief that disrespecting the masks invites bad luck, actors worship them before putting them on.

Mask artists also treat their craft with great respect. They never start their work without bathing. Since masks are aesthetic creations used in mythological storytelling, the artists also need to have a good grasp of the poetic descriptions of the characters in the texts. Prior experience of drawing or painting can be helpful in creating quality masks.

Types

The morphological features of Sattriya masks are usually derived from natural forms. The masks possess human (anthropomorphic) or animal attributes (theriomorphic), or both. There are two types of masks—loukik (worldly) and oloukik (otherworldly, supernatural). Masks based on natural forms of human beings and animals are known as loukik mukhas. On the other hand, oloukik mukhas are mythological characters with exaggerated features, including the 100-hooded Kaliya Nag, 10-headed Ravana, and Brahma with four faces.

On the basis of structural process, masks are divided into three types:

Mukh mukha or Mur mukha

Masks made only to cover the face of the actor are known as mukh mukha. During performances, actors wear these masks over their face and cover the rest of their body with colourful cloth. Characters like Maris (Maricha), Xubahu (Subahu), Chakrabat, Upananda, Surpanakha are enacted with mukh mukhas. (Fig. 2)

Bor Mukha or Su Mukha

These masks cover almost the entire body of the actor. Various parts of the mask are made separately before being assembled during the performance. The head of the mask is called mukha and the body is called su, which is why a bor mukha (large mask) is also called mukha-su or su-mukha.

The actor’s body from the waist down is covered with a skirt-like garment—mekhela, ghori or ghagra—hiding the legs from the audience. The bor mukha is around eight to 10 feet tall, much taller than the actors who can barely reach the chest or stomach of the mask. They view the audience through the tiny holes near their eyes. These masks are heavy but since they are made of bamboo, they can be carried with little difficulty.

The size of the masks reflects the majesty of the characters like Ravana, Narasimha, Moi Danava, Narakasura, Banraja (or Banasura) and Kumbhakarna. As they are three-dimensional, they resemble sculptures (Fig. 3).

Lutukai or Lutukori or Suti Su Mukha

Lutukori mukhas are smaller than bor mukhas. Their heads are not tied to their bodies. Since body parts are separate elements in lutokori masks, they allow ease of movement. The actors wear these masks for the roles of demons such as Putna, Taraka, Trishira, Dundubhi, Shankhasura and Bakasura. These masks are seen more during the Rasa festival than regular bhaona performances. (Fig. 3)[6]

Wooden, Fabric and Earthen Masks

Xaasor mukha is a type of mask made with basic bamboo, wooden or earthen frames, by pasting around 10 layers of paper pulp or cotton fabric on it. The gum required for pasting the layers of paper is made of wheat flour, seeds of kendu tree and hawthorn. Other important ingredients include kumar mati (potter’s clay) and cow dung, especially used in making fabric masks. In this process of mask making, multiple masks can be produced using the same xaas (mould or frame). Actors find these masks convenient because of their light weight. Although its simple production process makes it commercially viable, it dilutes the originality of the bamboo mask culture of Sankardeva.

While making fabric masks, required amount of cotton is stuffed inside double layers of cloth and given shape by stitching its boundaries. Though used mostly for mukh mukhas, fabric might also be employed in lutukori mukhas.

The various other materials for mask making include earthen pots, old, round bottle gourds and the sheath of betel-nut tree. These masks are either used in paddy fields to keep birds from destroying newly germinated seeds or for children’s amusement.

The practice of making masks from kuhila (pith plant) is believed to have existed in Bongaigaon district even before Sankardeva’s era. Miniature kuhila masks are regularly used in puppet shows in Assam.

Raw Materials for Mask Making

Masks are made from perishable raw materials like bamboo, cane, potter’s clay, cotton cloth, cow dung, jute fibre, paper, sholapith, and natural colours. (Figs 4 and 5) Thus, they cannot be preserved for long.

Bamboo mask making requires two-to-three-year-old jatibanh (a type of bamboo). Other species of bamboo are too thick to bend and their splits crack easily. The bamboo has to be cut into two to three hollow pieces (paab). Traditionally, bamboo pieces are kept in pond for about a week so that glucose seeps out and insect attacks are preempted. Alternatively, the bamboo pieces are boiled in water with lime.

Potter’s clay is preferred for making the base of the masks, because it is sticky and pliant and becomes hard once it dries. Cow dung is also used but it has to be calves’ waste, which is smoother and less fibrous. A small amount of kerosene is mixed with cow dung, as it acts as a disinfectant and deodorant.

The masks are painted with natural colours extracted from hengul (vermillion) for red, hiatal (arsenic) for yellow, indigo for blue, khorimati or dhawalmati (white clay) for white, tree leaves for green, and ash collected under an iron pan or kerosene lamp (chaki) for black. Hengul and haital are ground on a stone slab (pota) for at least a week to get the ideal luminescence. (Figs 6 and 7) The more it is ground, the more it glows. Colours are stored in different bamboo tubes. Gum mixed with colour are extracted from wood apple or tamarind. Sholapith is used to lessen the weight of the mask and mould facial features while jute fibre is used for making hair.

In the past, artists used pigeon feathers, hair of goat or squirrel, and jute fibre to make colour brushes on bamboo sticks.

Process of Mask Making

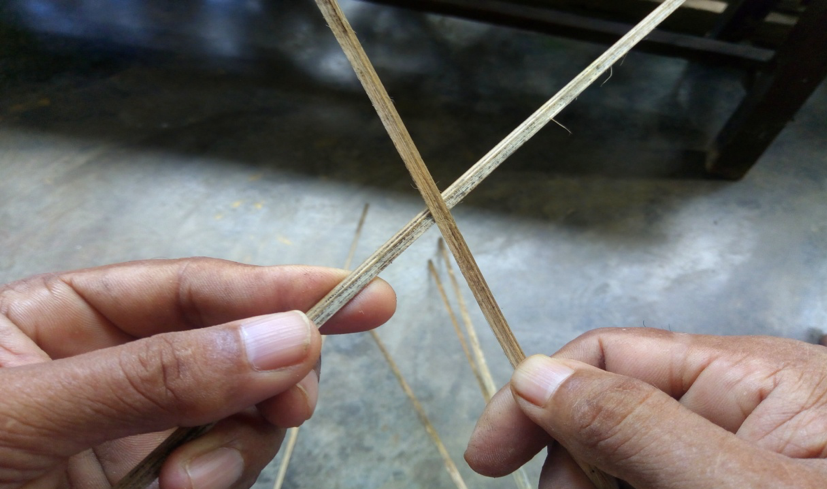

The process of mask making requires split bamboo to be arranged in a hexagonal shape.

In Assam, paddy seeds to be sowed the following year are carefully kept in a bamboo basket called tum, which is weaved in open hexagonal pattern. Since paddy is considered Lakhimi (Lakshmi), the goddess of wealth and prosperity, the guiding theory of making masks from these hexagonally arranged bamboo is called Lakhimi sutra. It is also known as Vishwakarma mur (theory), after the presiding deity of craftsmen and architects. (Fig. 8)

To make the basic structure of the mukh mukha, 32 hexagons are formed out of 18 splits of bamboo. (Fig. 9) Its edges are trimmed and it is encircled with cane. Small pieces of cotton cloth dipped in potter’s clay are placed on the skeleton for the base layer of the mask.

In the second stage, a mixture of clay and cow dung is applied on it with a bamboo scraper (karani), and the features of the mask become clearly visible. Then comes chehera-diya (giving the appearance), when the mask is dried in the sun, and features like moustache, crown, hair and ornaments are added to it. While it is still semi-dry, fabric dipped in clay is glued to it, and it is again smoothened by the scraper. Cow dung provides the mask a smooth finish, and it is left in the sun. (Fig. 10)

Finally, the masks are painted to be displayed.

Changes

Mask artists are well aware of the need to continue and promote the art of mask making in its traditional form. However, it is difficult due to lack of time and the cost of raw materials. For instance, hengul and haital are expensive colours and the process of painting with them is time-consuming and labour-intensive. The unavailability of the once-abundant natural resources is another factor that has hastened the shift towards synthetic colours.

Masks are no more kept inside the naamghar or su ghor but in a museum-like room for viewers. However, they are still made following the Lakhimi sutra, and often in traditional patterns. In recent times, masks have been widely embraced by Assam’s modern dramas and performances, furthering their appeal.

Innovations

Conventional masks restricted the actors to static facial expressions. But this has changed with innovators like the Majuli mask artist Dr Hemachandra Goswami, whose masks allow actors not only to move their limbs but also their eyes and lips, making the performances livelier without compromising on the aesthetics.

Goswami’s masks use aspects of lutukori mukhas in bor mukhas, making them more mobile. Similarly, he fuses the flexibility of puppets with the lutukori mukhas to create putola (puppet) mukha. His masks can be dismantled into small pieces, making them easy to carry.

According to Goswami, such innovations can go a long way in popularising this art form and making it commercially viable, which is an absolute necessity for mask artists.

To promote the art of mask making, artists now hold workshops both within and outside the state. They also make small masks in the form of wall hangings, which are popular among the masses.

Challenges

Despite its cultural significance, mask making is not as widely embraced as it needs to be. While the craft is part of the Sattriya culture, it is not practised in all satras. Those that use masks are mostly based in upper Assam, especially in the Majuli island. Notun Samaguri Satra (Majuli district), Khatpar Satra (Sivasagar district) and Bor Alengi Bogiai Satra (Jorhat district) are some well-known satras where the art survives. It has still not managed to gain enough following in lower Assam.

The financial disadvantages that plague mask making scare away students who learn the techniques in art schools but do not dare to become artists for a living. Government and social aids are hard to come by. Even the veterans who have practised the art form for decades live in destitute conditions with no definite source of income or pension.

It would not be incorrect to say that the art of mask making in Assam is fighting for survival. Unless a concentrated effort is made for its preservation, the state might lose a vital part of its culture.

Notes

[1] Khuliyabhaona is a theatre performance of the Darrang district. Wooden masks are used for characters like Ravana, Hanuman and Sugriv.

[2] Bharigan (also known as bhaugan) is a folk performance of the pre-Sankardeva period, prevalent especially in the south Goalpara region of Assam. It is practised by the Rabha community on the basis of themes from the Ramayana.

[3] Neo-Vaishnavism was a sociocultural and religious movement led by Srimanta Sankardeva during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

[4] Mahanta, ‘Ankiya Bhaonar Anyatam Aharjya Paramparagata Mukha Silpa.’

[5] Cihna Yatra was the first play written and staged by Sankardeva, where he exhibited the great cultural asset of Assam called Vrindavani Vastra, a tapestry exhibiting the saptavaikuntha (celestial abode of Vishnu). Sankardeva used masks for the first time in CihnaYatra. (Source: https://www.atributetosankaradeva.org/cihna.htm; accessed August 27, 2019).

[6] Rasa festival (Rasa Mohotsav) is a festival of Assam. The people of Majuli and Nalbari districts fervently celebrate this festival.

Bibliography

Barooah, Julie. ‘Assam’s Folk Performers Cling on to the Last of the Wooden Masks.’ Nezine.com, August 11, 2015. Accessed August 27, 2019. http://www.nezine.com/info/Assam%E2%80%99s%20folk%20performers%20cling%20on%20to%20the%20last%20of%20the%20wooden%20masks.

Goswami, Dr Mrinal Jyoti. ‘Sankardevar Natya-Paribeshonot Tholuwa Upadanor Kolatmak Prayug.’ In Srijansheel Pratibhar Garakee Sreemanta Sankardeva, edited by Dr Milan Neog, 100–116. Guwahati: Students’ Stores, 2006.

Goswami, Krishna. Mukha: Satriya Mukha Shilpa. Guwahati: Kasturi Press, 2016.

Kakaty, Keshab. Majuli: A Treasure House of Heritage. Majuli: Priyam Printers, 2015.

———. Majuli: The Paradise of Sattriya Culture. Majuli: Priyam Printers, 2010.

Mahanta, Akhyai Jyoti, and Udeepta Phukan. ‘Tete-a-Tete with Hemchandra Goswami, Eminent Mask Artist from Majuli.’ Discover North-East, February 8, 2017. Accessed August 27, 2019. http://discovernortheast.in/hemchandra-goswami/.

Mahanta, Jadav Chandra. ‘Asomor Mukha Sanskriti u Nirman Pranali.’ N.p., December 19, 2011.

Mahanta, Reba Kanta. ‘Ankiya Bhaonar Anyatam Aharjya Paramparagata Mukha Silpa.’ In Bhaona Darpan, edited by Raktim Ranjan Saikia and Monoranjan Bordoloi, 70–8. Jorhat: Sankalan Koch Samiti, 2003.

Medhi, Birinchi Kumar, and Arifur Zaman. ‘Tradition of Mask Making in a Vaishnavite Monastery of Assam.’ n.p., n.d.

More, Akash, and Nayan Shrimali. ‘The Divine Art of Disguise . . .,’ Gaatha: A Tale of Crafts, September 12, 2011. Accessed August 27, 2019. http://gaatha.com/assam-mask-making/.

Pisharoty, Sangeeta Barooah. ‘Of Theatre, Masks and Tradition— Keeping Folk Art from Assam's Majuli Alive,’ The Wire, February 15, 2017. Accessed August 27, 2019. https://thewire.in/culture/masks-hem-chandra-goswami-majuli-theatre-assam.