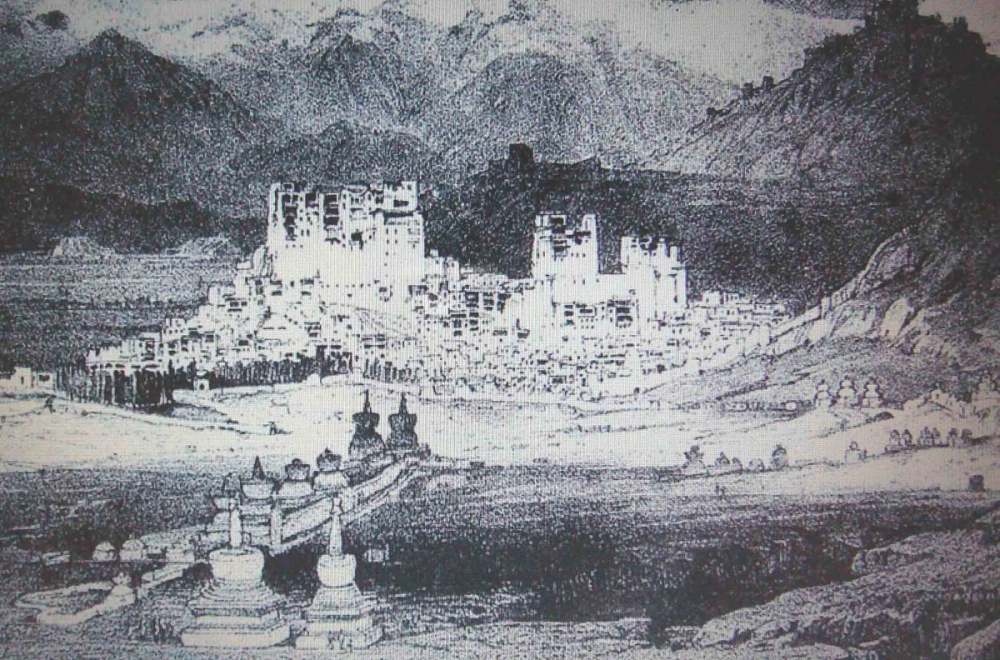

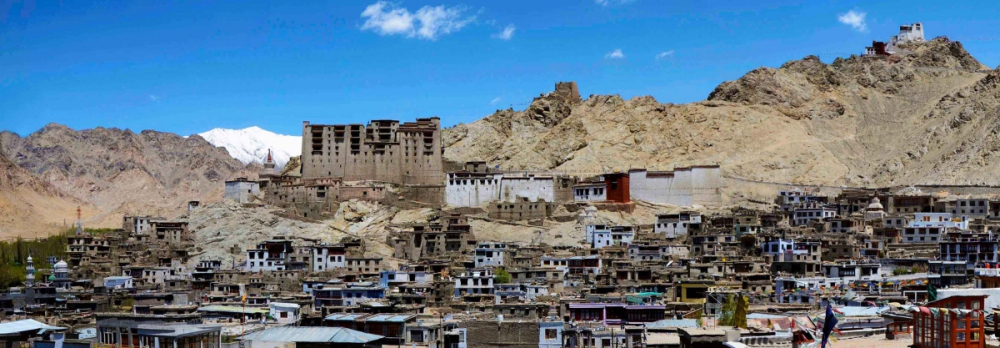

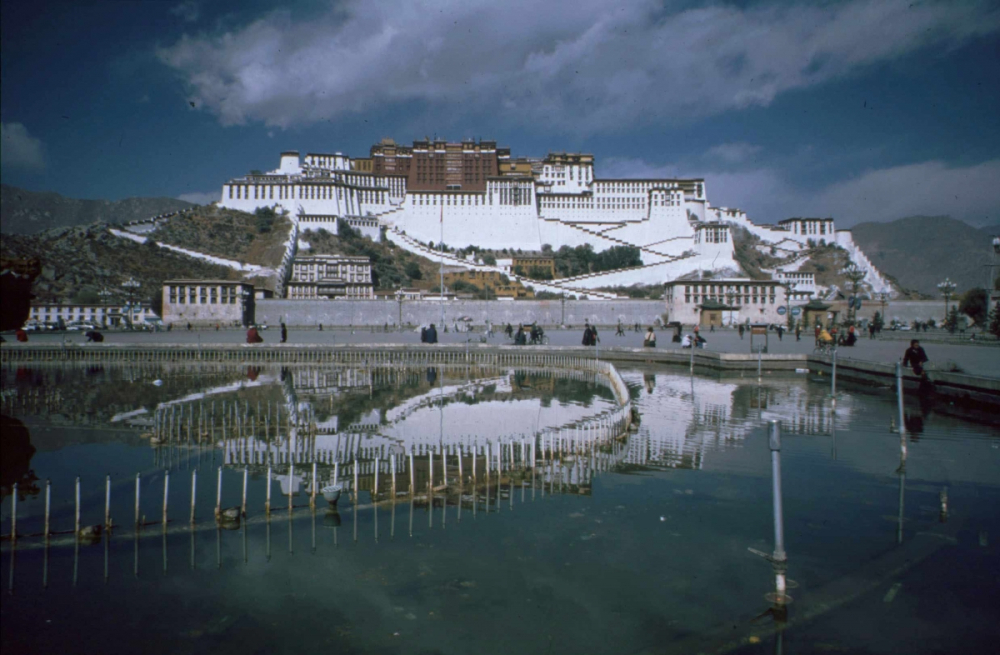

The imposing nine-storeyed seventeenth century Leh Palace greets people as they approach Leh. Perched high on a hill, the structure looms over the town’s temples, mosques and houses spread out below. Over the years, the familiarity of this visual image has become legendary, as it is the main subject of numerous sketches, paintings, and photographs of the region (Figures 1 and 2): ‘Leh . . . was particularly well served by a stream of European travellers, sportsmen, army officers, diplomats and missionaries. They came frequently with their cumbersome box cameras and glass plates, and they chose the same views . . . the dramatic picture of the town, palace and castle from the Lhato hill to the south’ (Harrison 2017: 17). At the time when it was built, it was the highest building in the Himalayas—until the construction of the 13-storey high Potala Palace in Lhasa a few years later (Figure 3). ‘The Palace of Leh antedates the Potala . . . and is on a much more modest scale; but the two buildings are clearly in the same tradition, as are the great monasteries of both countries. Domestic architecture too is an expression of similar canons of style, though adapted to a different function’ (Rizvi 1996: 3).

The Leh Palace is also called Namgyal Palace or more appropriately, described in local folklore and songs as, Lechen Palkhar—the Victory Palace of Leh. It was built in the early seventeenth century by King Sengge Namgyal (1590–1640 AD).[1] Popular traditional songs about the palace have poetic references to its construction, including descriptions of the construction materials used and where they were brought in from—starting with the auspiciousness of the day the building started. A song titled ‘Lechen Palkhar’ goes like this[2]:

When the magnificent palace of Leh was built,

It was the day when stars and time synchronised.

When Ladakh’s magnificent palace was built,

Incense and offerings were made all around.

The top of Leh Palace touches the heavens,

The foundation of Leh Palace touches the subterranean world of spirits.

The beams of Leh Palace were

Brought in from the thick grove of Alam Tilat.[3]

The mud of Leh Palace was

Collected from the middle of Chushot Stongbu.

The expert mason laid each layer,

The High Lama [monk] blessed them

Stagsang Raspa blessed each layer.[4]

The song also praises the lama Stagsang Raspa (1574–1651 AD), who was the spiritual guru (Ula) of the king Sengge Namgyal, who built the Leh Palace. It is believed that Stagsang Raspa was not only an enlightened Buddhist saint, but also an experienced and tireless traveller who had been to parts of the Middle East, Arabia and Afghanistan. ‘Stag’ in the name of Stagsang literally means tiger, and the king’s name ‘Sengge’ means lion. It is said that together the ‘Tiger Lama and Lion King’ built Leh into a sophisticated and cosmopolitan trading town, making it the economic, social and cultural centre of Ladakh. It became the centre of power for Ladakh as the king expanded the area under his control; his territory reached as far as Guge-Purang on the Nepal border in the east and the entire Purig area in the west. Prior to this, the capital had been in Shey (about 15 kilometres away) but as Leh was growing in importance as a trading centre, Sengge Namgyal saw it more advantageous to be in the centre of the economic hub—so as to enable better control and larger benefits.[5]

The Architecture of Leh Palace

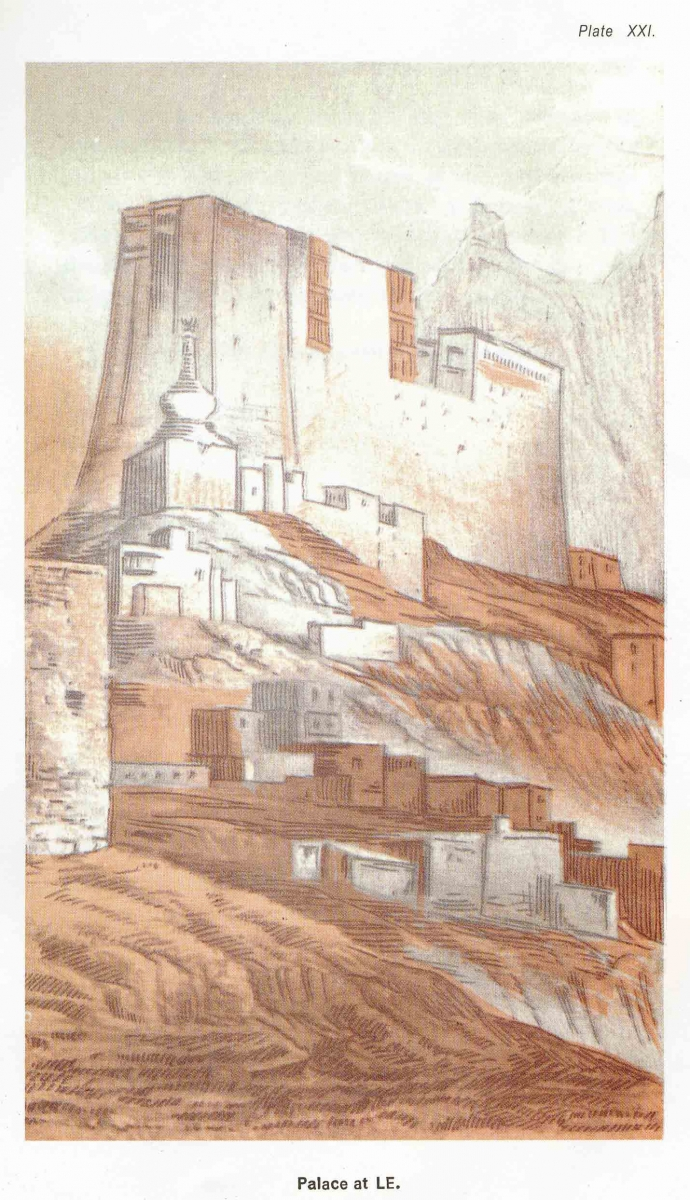

The royal palace of Lé is a large, fine-looking building that towers in lofty pre-eminence over the whole city. It is 250 feet in length and seven stories in height. The outer walls have a considerable slope, as their thickness diminishes rapidly with their increase of height. The upper stories are furnished with long open balconies to the south and the walls are pierced with a considerable number of windows. The beams of the roof are supported on carved wooden pillars and covered with planks painted in various patterns, on the outside. The building is substantial and plain; but its size and height give it a very imposing appearance. (Cunningham 2005: 312-313).

Alexander Cunningham provided one of the first detailed descriptions of the palace, when he visited Leh in 1854; and almost every traveller since then has remarked on the building’s size and grandeur (Figure 4). In oral traditions, it is said that Stagsang Raspa suggested that the palace be built in the shape of his robes which were that of a Tibetan monk’s. The robe has two folds in the middle and two on the sides and the design of the dress is upwardly tapering, with a wide and thick base. Further, it is believed that on the completion of each floor, Stagsang Raspa would bless it with his footprint and pray for the building’s strength and long life.

Fig 4. ‘Palace at LE’. Watercolour by Alexander Cunningham, 1854, Plate XXI.

The architectural layout of this nine-storeyed towering building suggests that it was more of an administrative building than merely a king’s residential palace. One of the key contributions to the palace’s design and construction was made by a skilled craftsman called Chandan Ali Singge. He was a Balti Muslim who was also known as Shinkan Chandan or carpenter Chandan (Sheikh 2005: 41).[6] Prior to Leh Palace, Chandan is said to have built the palace in Chigtan, which today stands in ruins (Figure 5). Local oral sources say that Leh Palace took three years to complete and the king was so pleased with the structure that, not wanting Chandan to be able to repeat the feat, he amputated his right hand. However, it is said that, despite that Chandan went on to build palatial buildings in Hanle, Rudok and other places (2005: 41).

The palace is built from locally available materials such as stone, wood (juniper, poplar and willow), sun-dried mud bricks and markalak (waterproofing clay). The materials were brought in from neighbouring villages around Leh, mainly Phyang and Sabu (Tashi Rabgyas 1984: 183–184). It is said that the stones were brought from Phyang village through a system called ‘war len’, wherein people would line up in a very long single line from one point to another, and then transfer items from one person to another.

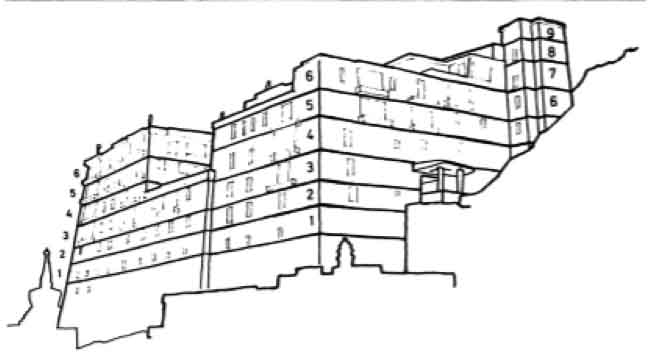

Fig. 6. This sketch identifies the nine levels of Leh Palace. Sketch courtesy Corneille Jest and John Sanday, 1983.

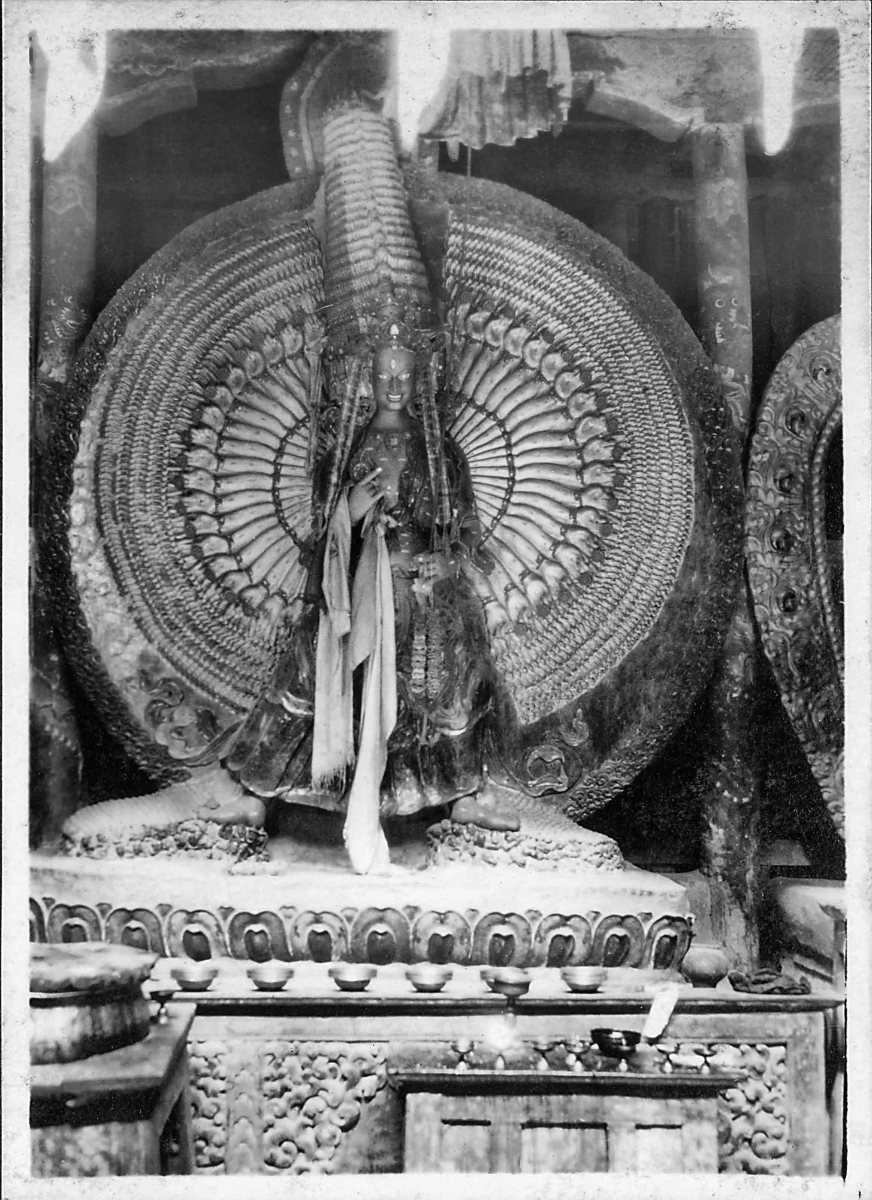

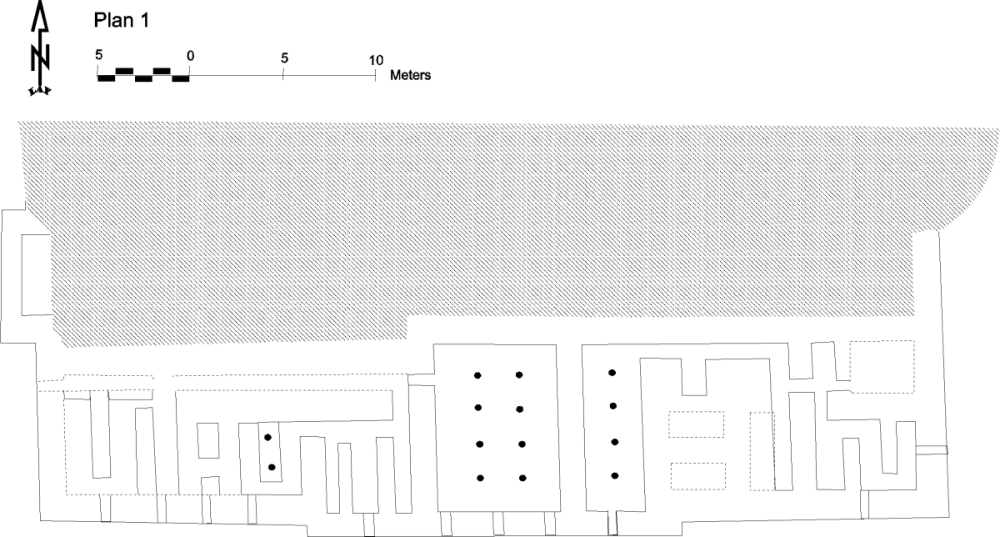

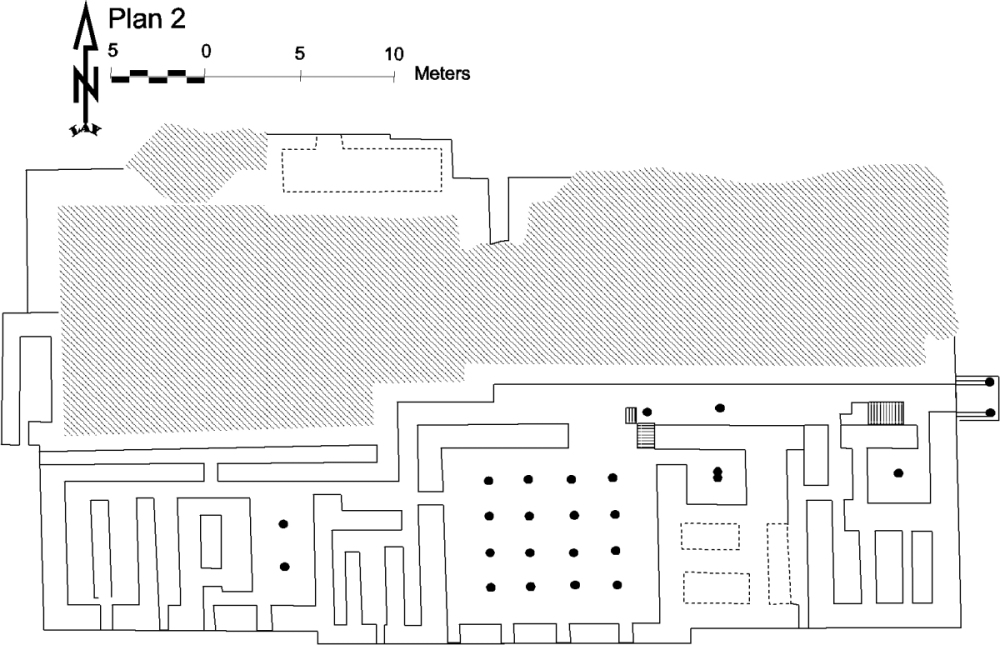

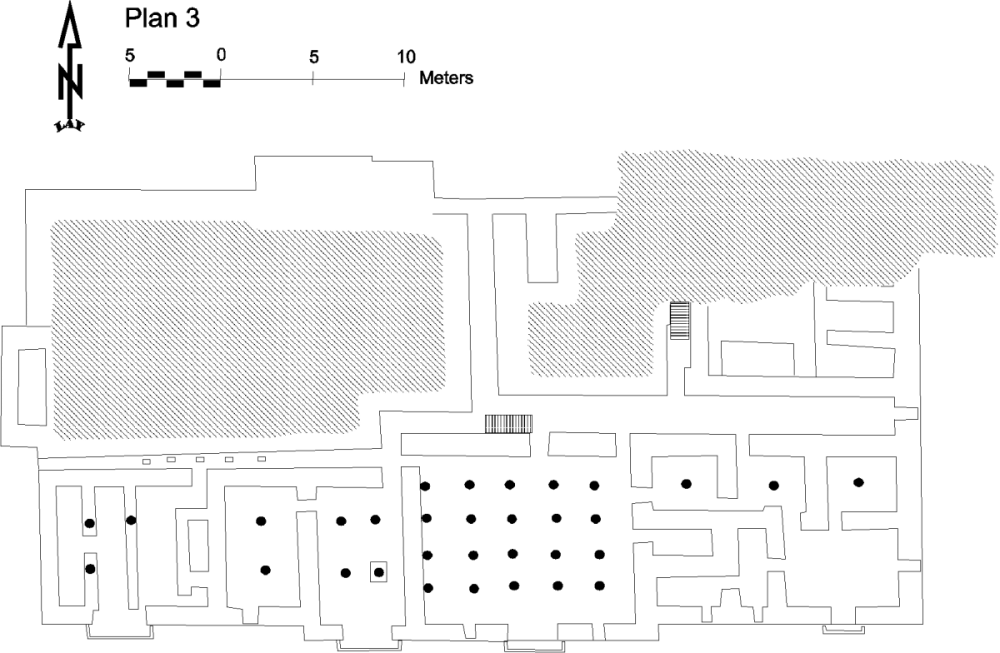

Ladakhi buildings follow regional Himalayan and Tibetan patterns of massive masonry walls, enclosing a timber structure of columns and beams supporting a flat earth roof (Harrison 2017:11). There are nine floors to the palace; the height of the structure is 58 metres from the base of the walls on the southern elevation to the summit of the ninth level (Figure 6). The main entrance porch is on the fourth floor of the palace which is where the administrative offices were housed. Dukar Lhakhang is also situated here; the temple (lhakhang) contains a stucco image of Dukar (gdugs dkar), also known as the ‘Lady of the White Parasol’, who is the triumphant thousand-armed form of the goddess Tara (Figure 7). There is another chodkhang (chapel) on the fifth floor, and on the uppermost roof is the lhatho—shrine to the gods (Figure 8). Till today, both temples are taken care of by regularly appointed monks from the Hemis Monastery. A plan of the various levels of the palace can be seen here (Figure 9).

Fig. 7. The image of Dukar in the temple at Leh Palace. Photograph by Rupert Wilmot, 1931; courtesy R Wilmot, R Bates and N Harman, Lost World of Ladakh: Early Photographic Journeys in Indian Himalayas, Stawa Publications, 2015

The main quarters for the king and queen and a large kitchen dominate the centre of the space on the sixth floor. The seventh floor has a throne room and a temple called Samyeling Lhakhang (bsam yasgling lha khang). The eighth floor has seven rooms in the northeast corner and there is another small shrine room on the ninth floor. The lowest floor housed the stables, while the second-lowest had storerooms and the third was for servants (Sheikh 2005:41).

The two big assembly halls on two floors are called Thag-chen Kong-Yog, which literally means Upper and Lower houses, akin to a modern-day parliament. According to oral traditions, this is where 60 wise men called Ganmu Tukchu were invited from all over Ladakh to discuss and brainstorm on institutional matters related to socio-cultural frameworks of Ladakh.

Fig. 9. Plans of the various floors of Leh Palace. Photograph by Sunder Paul and Tashi Ldawa Tshangpsa

The open terrace alongside the halls, in the centre of the building, is called kathog chenmo or the ‘Big Terrace’ (Figure 10). It was mainly used for performances, especially song recitals, music and dance. Meant for the royal family’s entertainment, these were performed by the takshosma (royal dancers), who were from 10 different families of Leh town.[7] One such member, Padma Angmo of the Nochung family, is 98 years old as of 2018, and is the only living takshosma; she remembers how the dancers were led by the Lhardak family and used to perform on kathog chenmo for the king and the queen mainly during Dosmoche and Losar celebrations. Though the royal family no longer lived at Leh Palace, they would come from Stok with a large entourage to witness the celebrations. Shon tses and Shondol were the main dance and song that they performed on kathog chenmo as the king and queen sat in their royal apartment and watched. She recalls the queen wearing a veil, watching the show from behind a panjiri or jali (wooden screen).

The south and east facades of the palace consist of a number of latticed and carved wooden balconies known as rabsal (Figure 11).[8] Similar woodwork can be seen in the old mosques and imambaras as well as the homes of the chiefs of Baltistan and other parts of Ladakh (Sheikh 2005: 41). In fact, the number of balconies in a house, at one time in Ladakh, denoted the resident’s status and prosperity.

Fig. 11. Wooden balconies on the south wall of Leh Palace. Photograph by Monisha Ahmed; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive, 2005.

The main entrance to the palace lies on its east side and consists of an elaborate wooden porch with three lions, alluding to Sengge Namgyal’s name and legacy (Figure 12). The canopy and brackets are elaborately carved, still bearing traces of paint, and their style seems to lie between that of the temple porch in Wanla and standard seventeenth century Tibetan style. The lion in the centre could be moved in and out of its box-like niche with the help of a mechanism within the palace; oral traditions say that it even opened its mouth and roared at unwanted visitors to demonstrate the king’s power (Figure 13).

During Losar (New Year) celebrations, a royal feast called Zhung Dral would be organised in Thagchen Hall, facing the open terrace. The king would sit on a high throne on this terrace and aristocrats, including his ministers (such as the Lonpo and Kalon amongst others), sat on seats lower than his to show their reverence and rank. A special dance called Drog-rtses Chenmo would be performed on kathog chenmo, with the king’s minister (lonpo) leading other aristocrats to the accompaniment of music by the kharmons (royal musicians).[9]

The construction of Leh Palace is said to be quite unique for its engineering techniques, including the traditional rammed-earth method—the walls of Leh Palace and most of the monasteries are a testimony to the strength and durability of this method. In addition to this is the mud-mortared stone technique that is used distinctively in the palace (Howard 1989: 218). This consists of a wall of mud-mortared stone (as opposed to, for example, cement-mortared ones). Sometimes, but not throughout, the stones are lightly dressed.

The visual texture of the wall faces comes about from the way the stones have been laid. The majority of the wall faces show random texture but a few have a distinct, banded texture. This banded texture is deliberately created by first setting a row of large stones, best faces forward, then using small stones to pack the spaces between them and to form a levelling layer for the next row of large stones (1989: 218).

Another interesting technique is the use of timber lacing of walls, a technique commonly used in many parts of the world including the Himalayas—from Hunza to Central Nepal (1989: 221).

Decline of the Importance of Leh Palace

In the summer of 1834, Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu declared war on Ladakh and sent his general, Zorawar Singh, to capture the region. The Dogra invasion succeeded and the Namgyal dynasty gradually lost its importance and power. The last king of independent Ladakh was Tsepal Migyur, also known as Tsepal Namgyal, who ascended to the throne in 1792. He was deposed by the Dogras in 1834 and by 1837 had moved to his palace in Stok, across the river Indus from Leh, where his descendants live till date.

With the king’s movement out of Leh, the areas surrounding the palace rapidly lost their grandeur and importance. Other residents in the area also followed the king and moved to areas further below Leh Palace that were developing at a faster pace than the rocky slope more immediately below the palace. Bereft of its residents and with a lack of regular maintenance, the structure of Leh Palace slowly started dilapidating and decaying. In 1991, the palace was sold to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). In 1995, the ASI started its renovation plans with some initial repairs to the structure. Then, in 1998, they began major repair and renovation work (Paul 2009; Paul and Tshangspa 2010).

Today, Leh Palace is a much-visited tourist destination (Figure 14). Visitors throng it to get a feel of the indigenous architectural style and to witness the splendid view of Leh town from the top of the building. Leh’s Old Town, Leh Palace, the Tsemo, various monasteries and houses that are built around the palace represent the cultural heritage of Ladakh. The need for conservation is imperative in the twenty-first century. These buildings are markers of the identity of the people of Ladakh and the changes that took place in this entrepôt called Leh, once a grand trading town that changed over time.

Notes

[1] Leh Palace is not mentioned in the accounts written by Fransisco de Azevedo, one of the first European visitors to Ladakh in 1631 (Wessels 1924: 109). Sengge Namgyal (probably born during the 1570–80 decade) is considered to be one of the greatest and the best known of the Ladakhi kings (Petech 1939:136).

[2] The Ladakhi song starts with:

Gle chen sku mkhar bo dzang tsa ne

Zhag po tang skar ma azom pay zhag yod

La dags sku mkhar bzhang tsa ne

Phogs tang dkar mchor khra chem chem.

Translation by Tashi Morup (2018)

[3] Alam Tilat refers to a grove of trees along the Zanskar Chaddar road. This is also mentioned in Tashi Rabgyas’s book titled History of Ladakh called the Mirror which Illuminates All (Bodyig) (1984: 183–184).

[4] Stagsang Raspa was the head of Hemis monastery; the monastery was expanded during the reign of King Sengge Namgyal.

[5] The construction of the palace may be taken to reflect the growing importance of Leh, vis-à-vis the ancient capital of Shey. ‘For it may have been about now that Leh, conveniently situated on the approach to Khardung-La, the main summer route to Yarkand, began to assume importance as a trading centre’ (Rizvi 1999: 69).

[6] Chandan Ali Singge’s actual profession is a little confusing, and it is not clear whether he was a carpenter (shing-khan) or a chief mason (rtsigs-pon). Both occupations play significant roles in the construction of buildings in Ladakh.

[7] Some of these families were: Lardak, Nochung, Gangba, Serchung, Gyaoo, Tongspon, Suku, and Tsaskan.

[8] It is this distinctive feature of the projecting balcony that sets Leh Palace apart from the Potala (Harrison 2017:8).

[9] The kharmons were mainly Muslims from Baltistan who had accompanied King

Sengge Namgyal’s mother Gyal Khatoon, a Balti queen, when she got married to the Ladakhi King Jamyang Namgyal (1580–1590 AD).

Bibliography

Ahmed, Monisha and Clare Harris (eds). Ladakh: Culture at the Crossroads. Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2005.

Cunningham, Alexander. Ladak: Physical, Statistical and Historical. New Delhi: Pilgrims Book House. 1854.

Harrison, John. The LAMO Centre: Restoration and Adaptative Reuse in Leh Old Town. Leh: The LAMO Trust. 2017.

Howard, Neil F. ‘The Development of the Fortresses of Ladakh c.950 to c.1650 AD’. East and West 39 (1–4): 217–288. 1989.

Jest, Corneille and John Sanday. ‘The Palace of Leh in Ladakh: An Example of Himalayan Architecture in Need of Preservation.’ Mountain Research and Development 3(1): 1–11. 1983.

Moorcroft, William and George Trebeck. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab (1819–1825). 2 Vols. London: John Murray. 1841.

Petech, Luciano. A Study on the Chronicles of Ladakh (Indian Tibet). Calcutta: Oriental Press. 1939.

Paul, Sunder. ‘Climate Change in Ladakh.’ In Ladakh Studies, edited by Kim Gutschow, vol. 25: 3–6. Kargil and Leh: IALS. 2010.

Paul, Sunder and Tashi Ldawa Tshangspa. ‘The Restoration of the Palace in Leh’ in Recent Research on Ladakh 2009—Papers from the 12th Colloquium of the International Association for Ladakh Studies, Kargil. Edited by Monisha Ahmed and John Bray, 72–96. Kargil and Leh: IALS. 2009.

Paul, Sunder and Tsering Phunchok. Ancient Palace, Leh. Leh: Archaeological Survey of India. 2017.

Rabgais, Tashi. History of Ladakh Called the Mirror Which Illuminates All. New Delhi: C Namgyal and Tsewang Taru. 1984.

Rizvi, Janet. Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. New Delhi: Oxford India. 1996.

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani. ‘Islamic Architecture in Ladakh.’ Ladakh: Culture at the Crossroads. Edited by Monisha Ahmed and Clare Harris, 34–43. Mumbai: Marg Publications. 2005.

Wessels, C. Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603–1721. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. 1924.