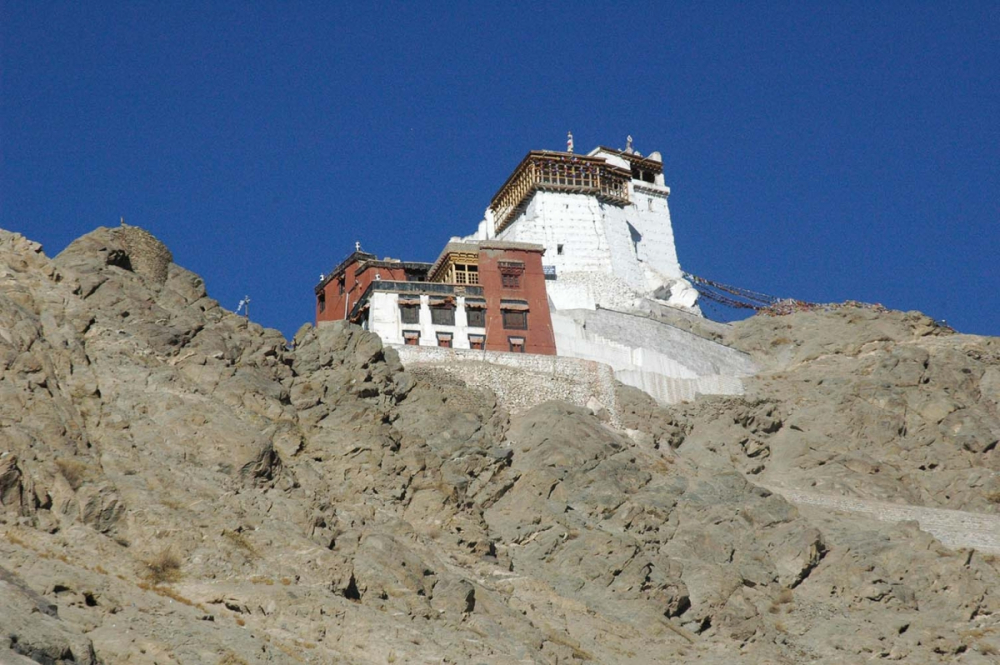

The historic Old Town of Leh is generally called Kharyog (mKhar-yog), referring to the residential houses and community spaces directly below the seventeenth century Leh Palace (Figure 1). Earlier, the houses were located within a walled fortification with five gates in different directions. It is said that there were only 120 houses within these walls, which were categorised into two equal parts popularly known as Skyanos Tukchu (tukchu means 60) and Gog-sum Tukchu. The palace stands as a dominating figure along the edge of the hill with other houses built along the gradient, in order of the importance of positions held by each family in the royal court—the most important being the Lonpo (Prime Minister's) House, right at the foot of the palace. A remnant of a dividing wall between the two parts (Skyanos and Gog-sum) still exists; however, the main protective wall encircling the town has almost entirely disappeared, except for minimal portions hidden in the labyrinth of narrow alleyways and maze of buildings. On the peak of the hill stands Tsemo Castle, the much older fort built by the predecessors of King Sengge Namgyal, who built the nine-storied Leh Palace or Lehchen Palkhar as described in popular folk songs (Figure 2).

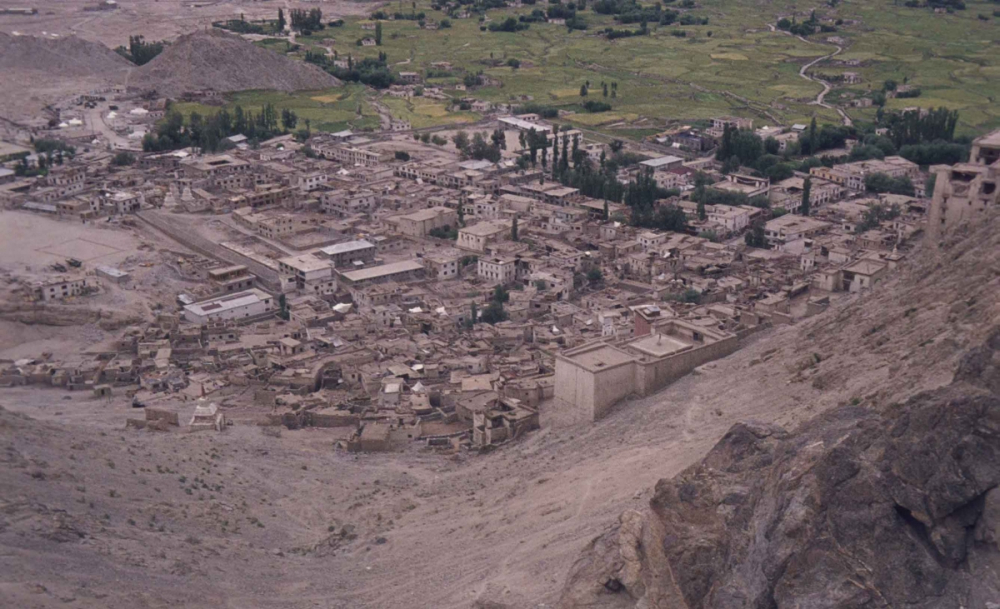

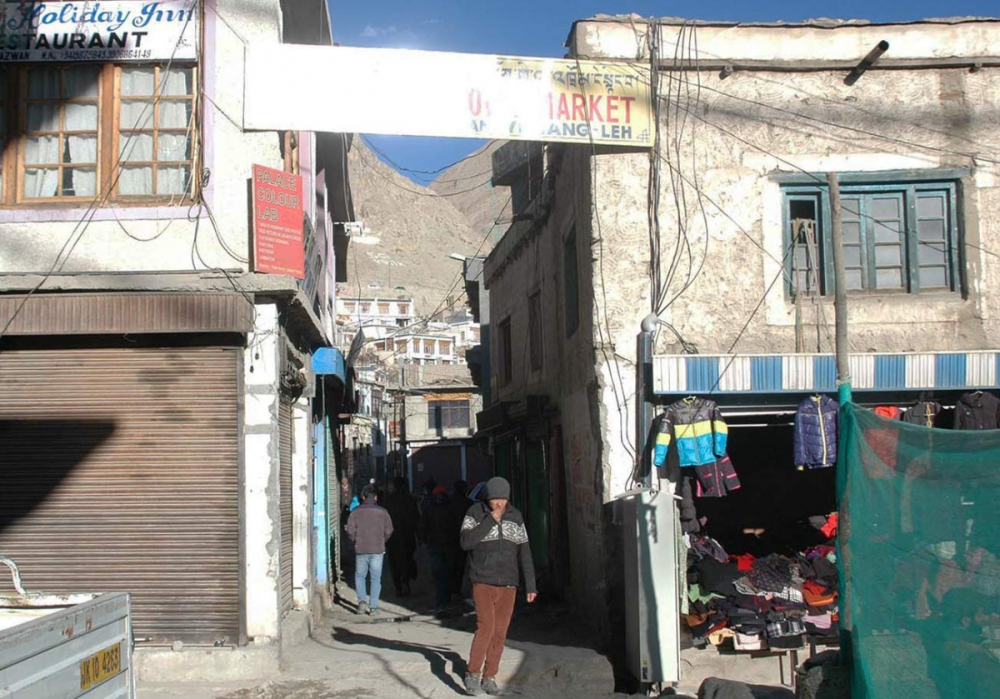

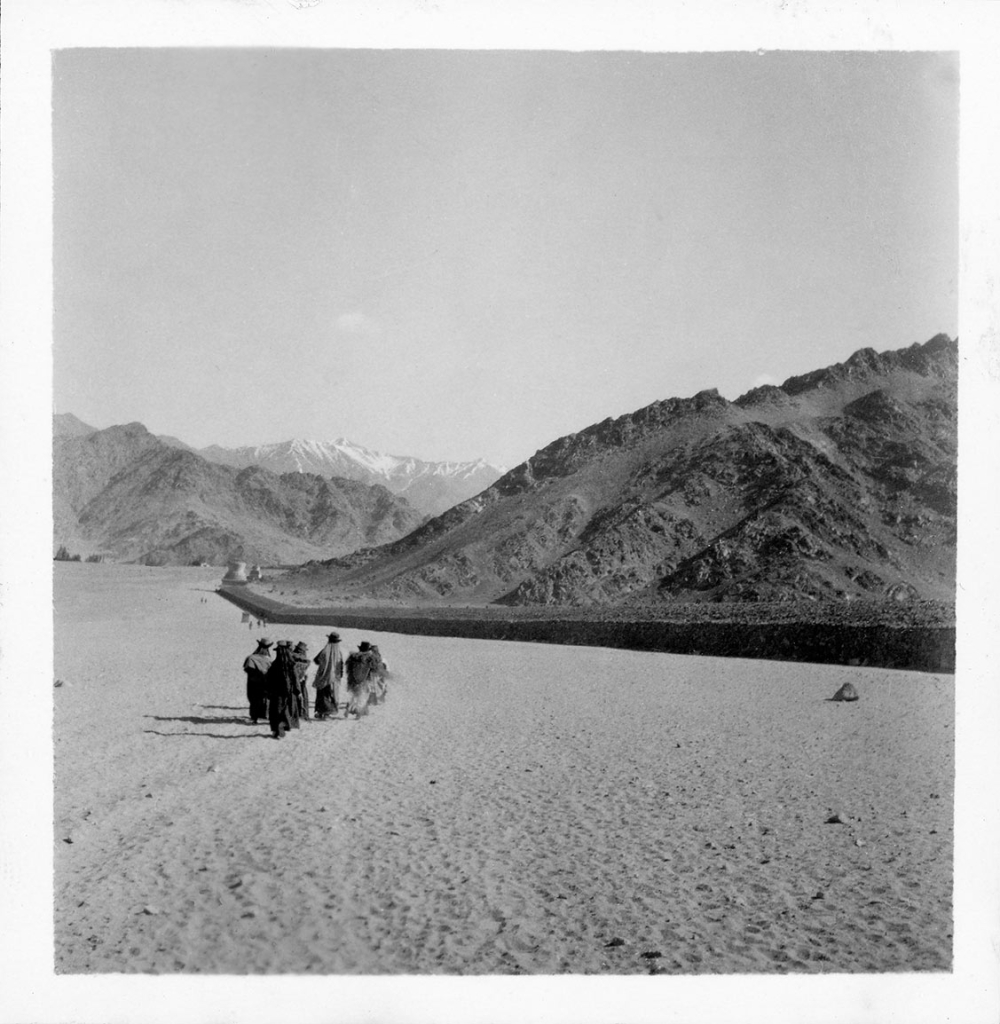

The whole settlement on the gentler slope of the hill facing south made a perfect place for establishing winter residences (gun-sa). Dr Phuntsog Angchuk, the owner of Munshi House, claims that his home existed much before the palace was built, and he believes that the township predates the construction of the palace.[1] This means that Old Town had its own settlement history independent of the palace. The community that lived here followed a shifting pattern of residence between their summer and winter homes; this practice was followed till the recent decades when the majority of owners abandoned their houses in Old Town (the winter residence) and moved to their summer residences in the greener, more fertile parts of the valley amidst agricultural lands (Figure 3a and 3b).[2]

Fig. 3a. A view of the Leh town from 1975 showing that the town ended at the Girls Higher Secondary School, on the lower left; the area where the Tibetan Gol Market (locally known as Bangladesh Market) is today, was still largely covered in fields. Photograph by Hans D Engelhardt, 1975; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive

The first permanent settlements in Leh are said to have been established on the marshy outgrowth of the Chhubi settlement, at the back of Tsemo Hill (Figure 4). This was during the reign of King Takpa Bumlde (1400 AD). In fact, the name Leh is connected to the Chhubi marsh that served as lhas or pastureland, which is pronounced as le by nomadic communities in eastern Ladakh.

The summer residences (yar-sa) are in clusters, embedded along the glacial stream of Leh (known as Leh Tokpo). The stream descends downhill from Phutse and Nangtse glaciers, located on the highest reaches of the valleys on either side of the Khardong-la pass which goes to Nubra. These clusters (rChutsos) begin with Gang-lhas upstream, the name that means ‘pasture on the higher ground’. Other clusters downstream are Gonpa, Khagshal, Samkar, Chubhi-Yangtse, Yurtung, Changs-pa, Shenam, Tukcha, and Skara at the end.

Owning a house below the palace was, in fact, a favourable factor in marriages; a matter of prestige when choosing a partner, as suggested by this old and well-known proverb, ‘Khar-Yog ga Khangpa, Zing-Yog ga Zhing.’ (A house below the palace, field below the water reservoir).

The proverb implies that unless a man has a house below the palace and an agricultural field next to a reservoir, he is not eligible to get married in Leh town.

As per the 1901 Bandobasti Khewat (land delimitation) records with the revenue department, the number of families in Leh was registered as 356. This suggests an almost three-time increase in the total number of households in Leh town (primarily, Old Town) from the original figure. The same revenue record gives the size of Old Town as follows:

Bandobasti Settlement [3]

No. Khasra 4356/6 Area 9.8 Kanals (Area around bazaar) [4]

No. Khasra 4380 Area 42.3 Kanals (Zangsti area)

No. Khasra 4465 Area 52.2 Kanals (Nowshara)

No. Khasra 4490 Area 88.3 Kanals (Stago Philok/Kharyog)

Abadi deh / Residential area, Leh.

A Heritage Precinct—The Historic Importance of the Old Town

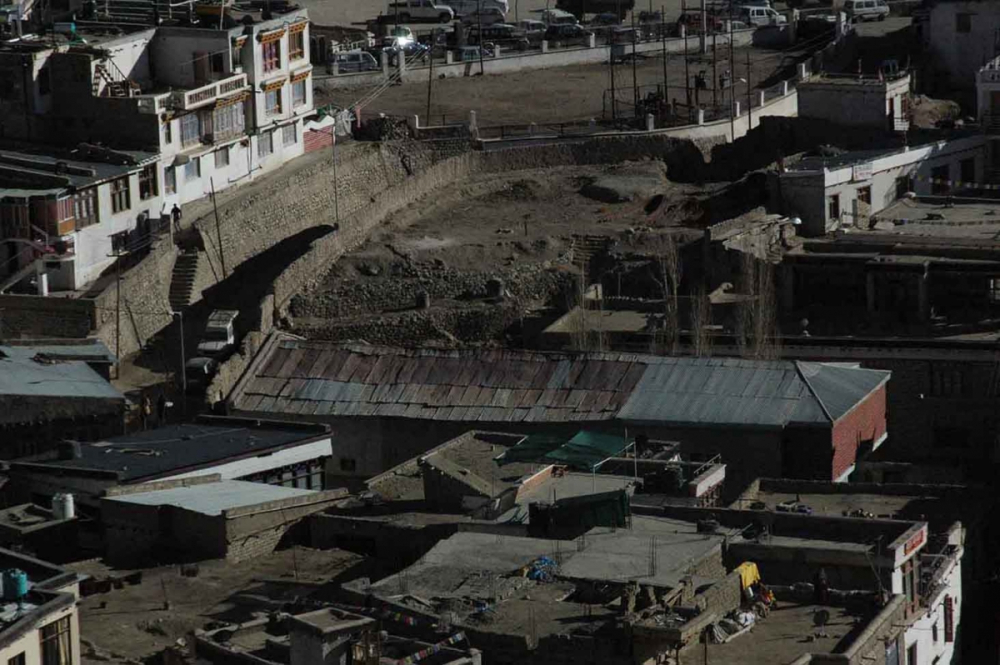

Old Town bears testimony to the architectural heritage and socio-cultural history of Ladakh, which demonstrates an indigenous aesthetic as well as links to Central Asia, Tibet and Kashmir. Situated behind Leh’s main market, the town covers an area of roughly 24.07 acres. This area is circumscribed by the polo ground to the south, the Balti bakeries in Chutey Rantak in the west and the motorable road going up to the palace in the east (Figure 5). Within this area, lie several important historical buildings including religious structures and Leh’s first cinema hall (Figure 6).

Fig. 5. Chutey Rantak Street with Balti bakeries on the left. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2018; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

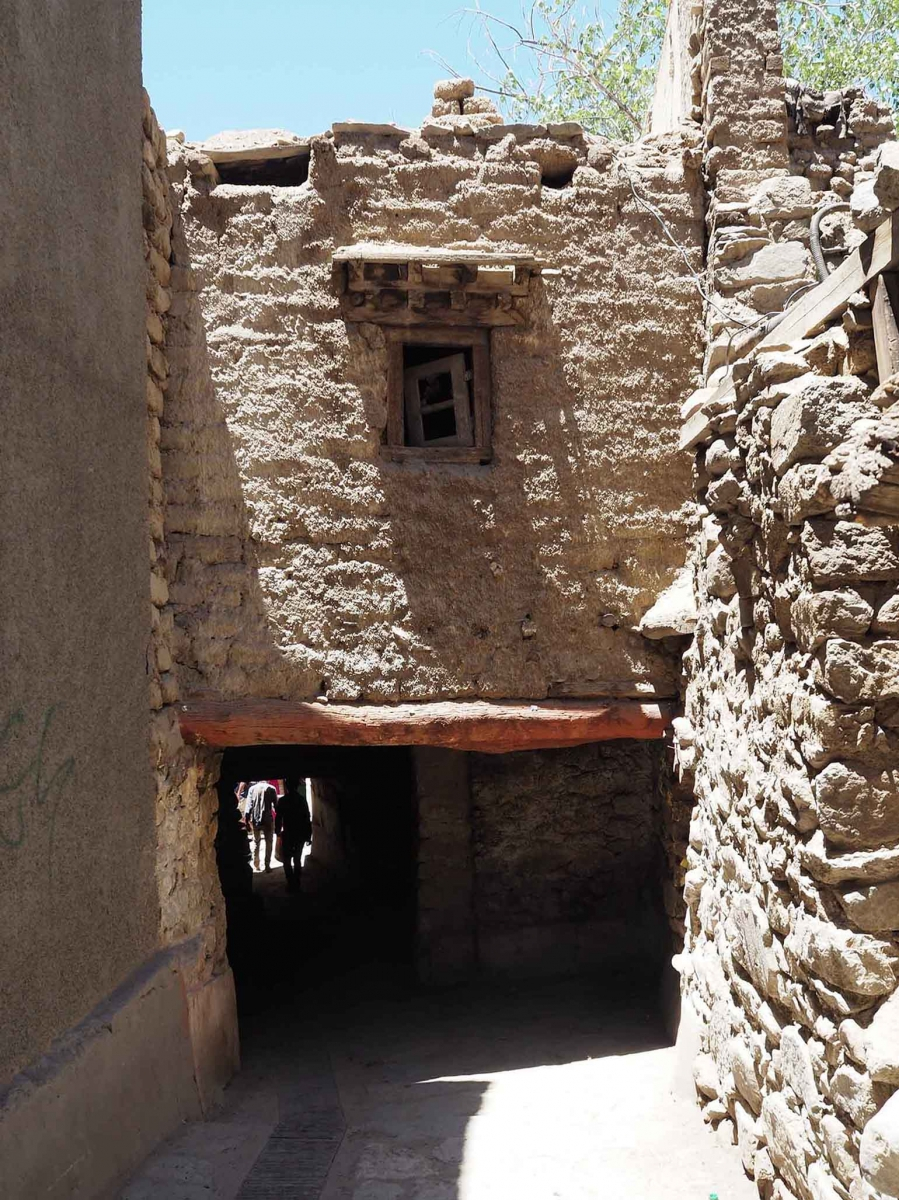

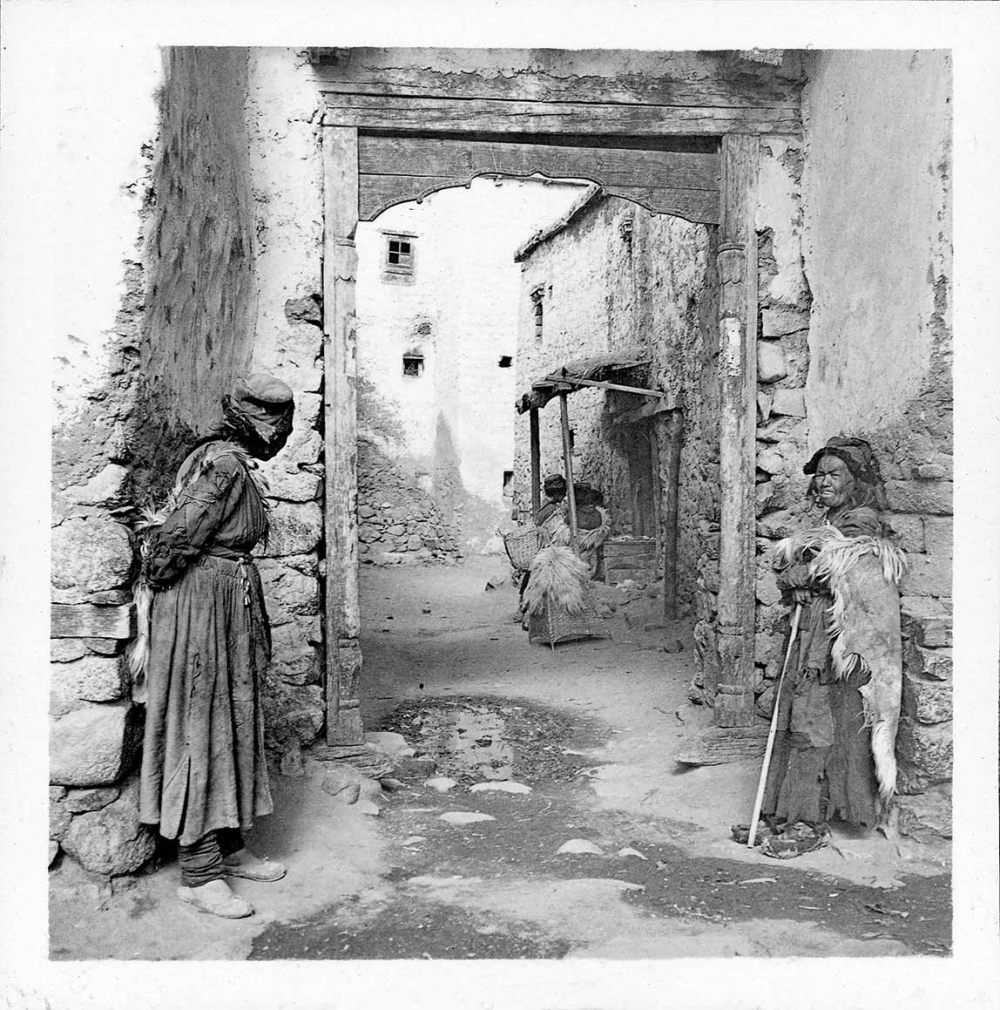

The main area of Skyanos and Gog-sum is made up of five wards: Kharyok, Stalam, Lobding, Stago Philog and Maney Khang. They are connected by a labyrinth of narrow, winding pathways, most of which are still accessible only to pedestrians (Figures 7a and 7b). Some of the wards are covered as the houses are built very close to one another and the roofs from the first floors protrude over the pathways.

The following rough sketch may help understand the location of these wards within the Leh town:

Chhubi Namgyal rTsemo

Leh Palace

Chhutay Rantak Kharyok

Maney Khang Stalam

Mosque Old Leh Town Skampari

Leh Town Lobding Stago Philoq

Leh Bazaar Nowshar

Note: Names in bold letters carry some important landmarks while others show adjoining areas.

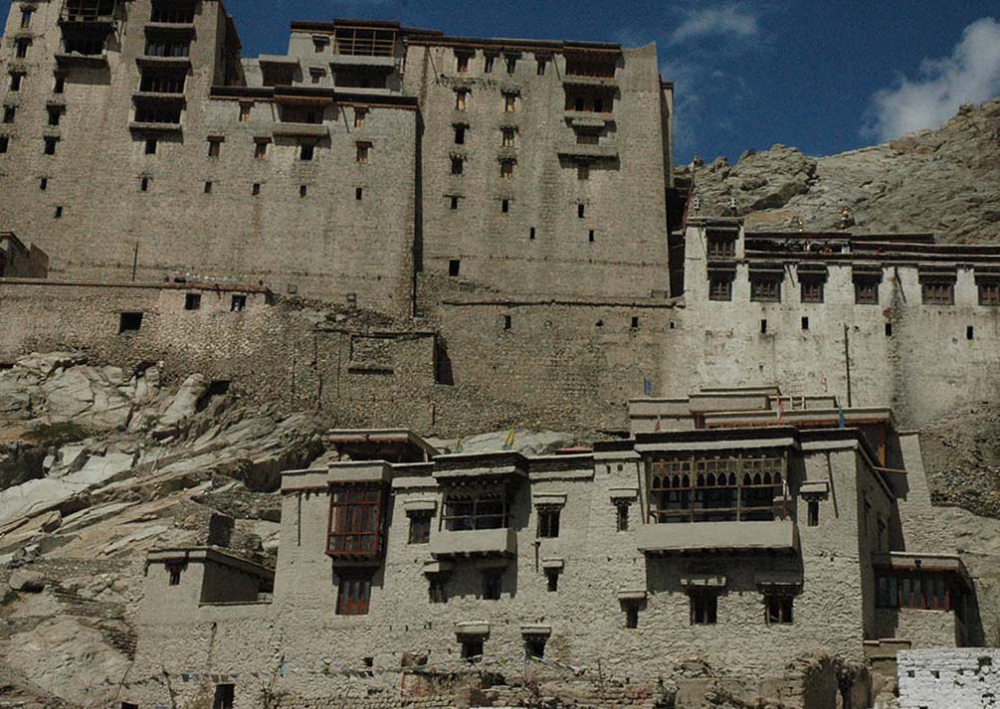

The area dates back to the first part of the seventeenth century, or earlier, when Leh Palace was constructed. The first king to take up residence at the palace was Sengge Namgyal, one of the most powerful rulers of the Namgyal dynasty. Most of the residents of Old Town lived here by virtue of their affinity to the king—his ministers, secretary, horsemen, tailors, jewellers, musicians and artisans, among others—and had accommodation of varying sizes and types depending upon their rank in the area below the palace. Thus, the area around the palace was the most important part of Leh, as well as Ladakh, as it played a crucial role in the political, commercial and cultural life of the region. Many of the homes that remain, display some of the best remaining examples of the vernacular domestic architecture of this time (Figures 8, 9 and 10).

There were a total of five gates that led to the inner part of the walled town of Leh under the Leh Palace; they opened at 6 am and closed by 8 pm. The main gateway was a wooden structure that led to the Old Town (Figure 11); now the entrance is through the main bazaar side of the street next to the Jama Masjid (Figure 12). The other four gateways were stupas (chortens) that functioned as gateways, called kagan (Figure 13).

Fig. 13. Stupas, also called kagan, functioned as gateways for the Old Town. Photograph by Sonam Angchok, 2017; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

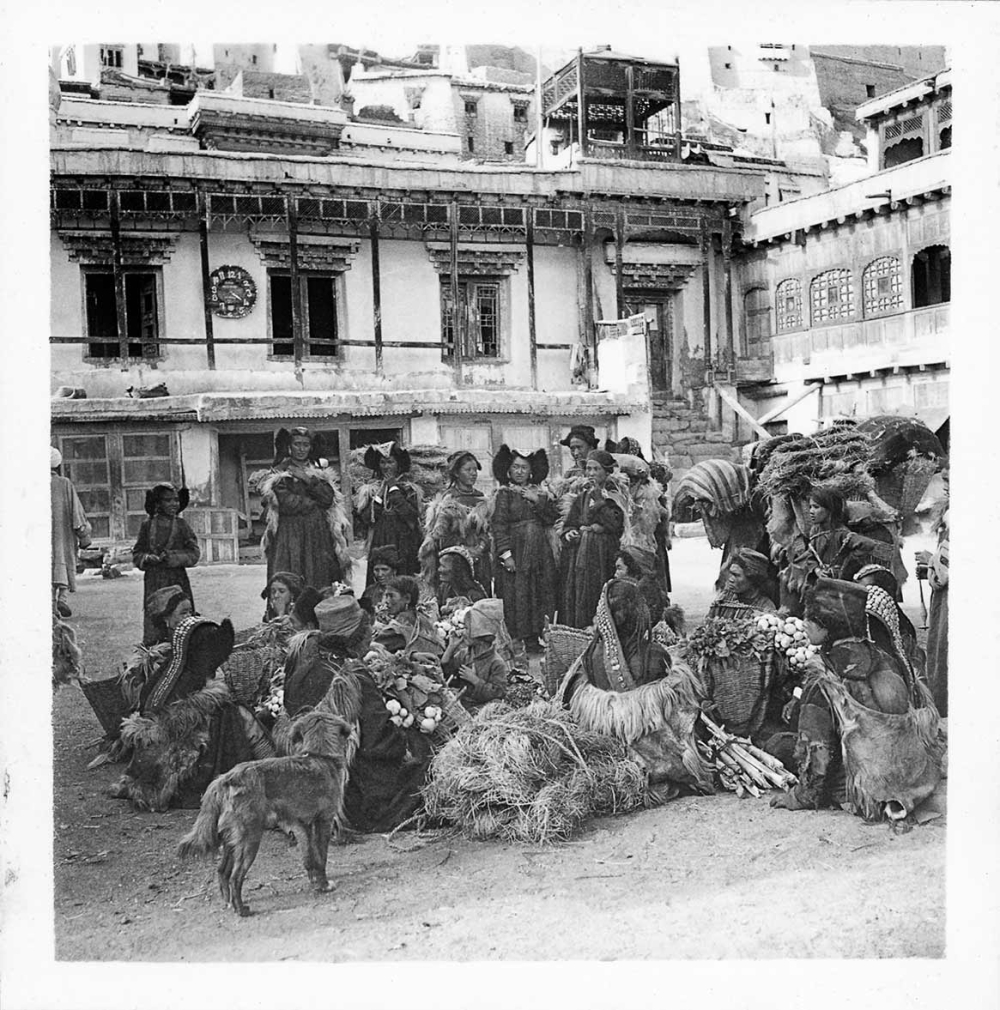

The main gateway into the town led to an area known as Maney Khang, traditionally an important public space for the residents who would sit around here and chat or offer prayers at the two monumental stupas (chortens) that mark its location (Figure 14).[5] The area was (and continues to be) a commercial centre with several shops, small eating places, workshops of jewellers and dyers, and a small rest house (labrang) of Sankar monastery (Figure 15). The caretaker monk (Kom nyer) of the Maitreya temple below the palace used this house as his residence (Figure 16). One of the back rooms of the house holds five ancient Buddhist rock-carved images. A little beyond Maney Khang was the location of the royal kitchen garden, which was known by the name Lobding meaning ‘land strewn with leaves.’

Fig. 15. A blacksmith’s shop. Maney Khang is a commercial area with many artisanal workshops and small eateries. Photograph by Rigzin Chodon, 2017; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Prominent temples in the town are Mahakala Temple on Namgyal Tsemo (victory peak) above the palace, Guru Lakhang (Padmasambhava Temple) and Chenrezig Lhakhang or Avalokitesvara Temple (Figure 17). There are many smaller shrines including the temple in the palace devoted to Dukar. Some of them have exquisite wall paintings, including the Red Maitreya Temple (Chamba Marpo) recently restored by Tibet Heritage Fund (Figures 18a and 18b).

Fig. 17. The Chenrezig Lhakhang. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2018; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Fig. 18b. Red Maitreya Temple wall paintings after conservation. Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2007; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

The first public mosque to be built in Leh was located in Tshas Soma or ‘new garden’.[6] It was built sometime after 1620 at the request of Muslim traders conducting business in Leh (Sheikh 2005: 37). It is a single-storey one-room structure with six wooden pillars, their capitals carved at the top in Ladakhi style. The mosque had stopped being functional by 1950, but has recently been restored by Leh Old Town Initiative (LOTI) exclusively for use by women. The Leh Mosque, popularly known as the Jama Masjid, was built during the reign of King Deldan Namgyal (1642–1694 A.D.). Around the mid-seventeenth century, the Tibetans invaded Ladakh and the king asked the Mughals for assistance to which Aurangzeb agreed. After successfully defeating the Tibetans, he made the king agree to three conditions of which only one was kept—to give a piece of land below the palace for building a mosque (2005: 37). The Sunni Jama Masjid now stands at the crossroads of the two main streets, dominating the main bazaar in Leh (Figure 19). It has gone through several renovations and rebuilding, with the latest beginning in 2017 (Figure 20). Further down the road is the Shia Imambara, built in the mid-nineteenth century during the reign of the Dogra king Ranbir Singh (1857–1884).

Fig. 19. The square in front of the Jama Masjid was often used for public meetings and for traders to sell their wares; women often gathered here in the late afternoons to sell vegetables. Photograph by Rupert Wilmot, 1934; courtesy R. Wilmot, R. Bates and N. Harman, from Lost World of Ladakh: Early Photographic Journeys in Indian Himalayas, Stawa Publications, 2015.

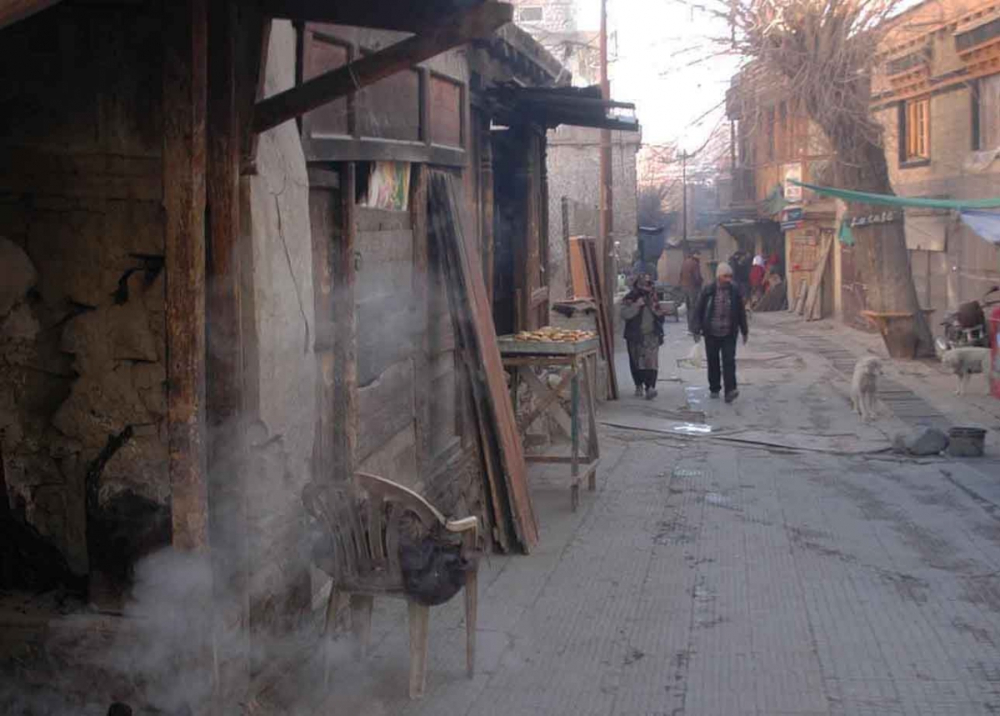

Two of the main pathways on the edges of Old Town were Chutey Rantak and Nowshar, both roads remain pedestrian-only till date. Chutey Rantak was originally called ‘Chuskor Rantak’ referring to a traditional mill for grinding grain that uses the force of water; usually, roasted barley grains as barley flour (tsampa or sattu) is a staple food in Ladakh. This place was built by the Baltis during Queen Gyal Khatoon’s time (first part of the seventeenth century). The main owners of the area where the water mill once existed are Nakpo, Ldumbu and Tongspon families. Perhaps because of the presence of the water mill, many bakeries came up in the area (Figures 21 and 22).

Fig. 21. Kashmiri bakers making kablama/ tabtan and kulcha in a tandoor oven in Chutey Rantak. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2018; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

A Lhar Chhang tree, known as gTsug Tor Lhar Chhang, stands in Chutey Rantak (Figure 23). Historically known as the gTsug Tor, the tree gets its name from its protective deity, Tsug Tor, Gyamo. The tree was planted by Stagsang Raspa, the founder head lama of Hemis monastery and the guru of King Sengee Namgyal. The king is said to have selected the location, which is a granite spur, like the shape of an elephant’s head. This tree must be at least 400 years old. Currently, the tree is taken care of by the Sikh community in Leh, who have renamed it Datun Sahib (referring to Guru Nanak’s toothbrush).[7]

Fig. 23. The lhar chang tree, Chutey Rantak, Leh. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2017; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

The Nowshar area originally consisted of a community hall which used to be the office of Basti Ram, the man credited for making Leh Bazaar. His residence, known as Basti Haveli (or Basti Ram’s haveli), was located beside it. Though now only the wooden entrance gateway exists, the local government has plans to restore the building (Figure 24).

Fig. 24. The entrance of the haveli of Basti Ram (on the left), a Dogra Tehsildar, is located in Nowshar. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2018; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Traditionally, the Nowshar area used to be called Chang-gali, where chang (local beer) used to be sold in some local houses by Ladakhi women. The street contains many interesting and colourful shops that sell a variety of fabric and traditional items like Ladakhi dresses (Stutung, Pabu, tipi, bok, kos,among others), local utensils and metal tools (Figure 25). Goldsmiths, tailors and barbers can also be found in this area, along with a few shops belonging to butchers and other meat vendors. Bam-e Duniya is a cooperative fair price office that also exists in the area. The shop of veteran astrologer Thupstan Jhanphan is also in this street; he sells traditional ritual objects, scriptures, and Buddhist religious books. In the heyday of Leh Bazaar, this area behind and almost parallel to it, thrived as a sort of alternative bazaar. Initially called Nau Shehar (meaning New City), it gradually became Nowshar.

Fig. 25. A shop front in Nowshar selling Ladakhi robes, ritual objects and a variety of textiles. Photograph by Monisha Ahmed, 2009; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Historical Homes in Old Town Leh

It is difficult to find written records about most of the family houses in Old Town; however, documentation is possible through personal narratives, songs and the way constructions have been laid out on the hill slope below the palace. Some of the families who held important positions appear frequently in books written on history and trade in Ladakh, as well as genealogies of Ladakh and Central Asia.

The palace is said to have been built over a settlement that already existed. Earlier, chieftains or vassal kings controlled different territorial parts of the region. Around the tenth century, they were unified under a single entity by a king from the Namgyal dynasty of Tibet. Shey was the first capital; Tigmosgam in Sham (lower Ladakh) was also an important strategic centre for rulers of Ladakh until the seventeenth century when the capital shifted to Leh and the town gained significance for its trading network. The region gradually became more consolidated and protected.

Each house of Old Town is accorded its position based on the family’s status and standing with the royal family. This can be understood by carefully observing the layout of the various constructions in the town. The Lonpo House sits at the top, barely a foot away from the palace. The next line of houses includes the Rupshu House, Ayu Kalon House, and Umla Nangso House. After the king, the Lonpo was considered the most powerful family. Their home is almost in line with the main temples in the vicinity of the palace. These houses and the temples were actually built beyond the existing city wall which divides Gog-sum—the old part of old town immediately below the palace—from Skyanos (literally meaning ‘beyond the wall’). These houses beyond the wall were apparently later constructions, added to the older town Gog-sum (meaning ‘three gates’ as found today in this area). As a result of Leh becoming the main centre or the capital in the seventeenth century, the process of incorporating important families around Ladakh led to the expansion of the town beyond the wall and the three temples of Maitreya built by King Tashi Namgyal (1500–1530 AD) who also built the Tsemo Castle. These were the first signs of urbanisation of Leh town, showing how a small town grew out of an ancient settlement and then was added to over the years—a practice that continues till date.

Below is a description of some of the important houses.

Ayu Kalon House

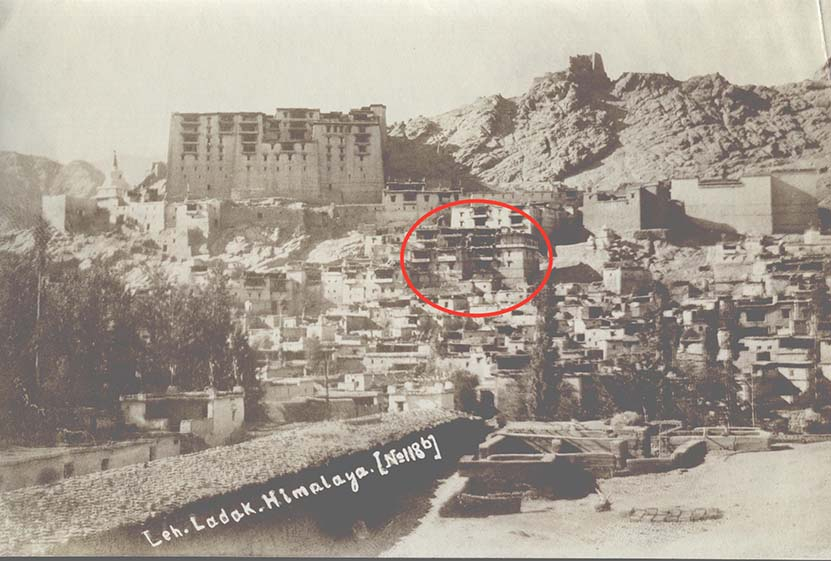

The once-magnificent Ayu Kalon House under the Leh Palace, now brought to ground, has a fascinating history (Figure 26). After the death of King Sengge Namgyal, his son Deldan Namgyal ruled from 1620 to 1640 AD. During that period the prime minister Ayu Mgarmo’s son, Kalon Chosnit, had a wife named Shema Zilzom, a very beautiful and charming lady. Deldan Namgyal got attracted to her beauty and charm. Filled with desire, he plotted to kill Kalon Chosnit so that he could marry her. He ordered some of his officials to stone him to death. They did so in the dark corridor of the palace entrance, however, the Kalon (prime minister) escaped but on his way to Ayu (about five kilometres from Leh), the men caught up with him and killed him.

Sometime after the prime minister’s death, the king sent his proposal for marriage to Zilzom; not wanting to offend the king, she wisely dealt with his delegates. She said she would accept the proposal if the king built a mane (prayer) wall in memory of her late husband. The king got his men to build the mane wall on the outskirt of the town. She further delayed her marriage by saying that the mane wall should be rebuilt in the shape of her perak (turquoise-studded headdress). The king complied and then sent his delegates to Zilzom again, who was at her home in Igoo further away from Ayu. She received the guests and served them tea and asked to allow her to pray for some time in the house chapel before leaving. When she emerged, Zilzom was in a nun’s attire with her head shaved. The confused king’s men narrated the incident to the king and on hearing that he deeply regretted his action and ordered the building of two big stupas at either end of the mane wall (Figure 27). Shema Zilzom’s son, Shakya Gyatso, was made the prime minister and a beautiful palatial residence was built below the palace next to the city wall beside the Munshi House. This house was dismantled many years ago and the descendants of the family now live in Ayu area of Sabu village.

Fig. 26. The Ayu Kalon House (encircled in red) when it stood tall on the right side of Munshi House (on the left), early twentieth century. Photograph M-T-1-248, courtesy Moravian Archives London (MAL).

Fig. 27. The famous mane wall that was built with two big stupas on either end. Photograph by Rupert Wilmot, 1934; courtesy R. Wilmot, R. Bates and N. Harman, from Lost World of Ladakh: Early Photographic Journeys in Indian Himalayas, Stawa Publications, 2015.

Munshi House

The Munshi House stands on the upper part of the town, below Gompa Soma and the eastern end of the royal palace (Harrison 2017: 27). It was once the residence of Togoche family— secretary to the king, which was a very powerful position. After the invasion of Ladakh by the Dogras, the term ‘Munshi’ was used as an official title for the secretary in the Ladakh court; it was a hereditary position.[8] Munshi Spalgyas, who lived in the nineteenth century and considered one of the most owners of the house, renovated the old building and added new rooms to the house.

It has been stated that the original construction of the Munshi House can be traced back to the early seventeenth century; the remaining buildings gradually extended over the centuries as new rooms with richly decorated interiors and balconies (rabsals) were added. The house has five levels on the hill slope with several rooms of which the main ones were the chapel on the uppermost level; around the courtyard there’s a large painted room with a balcony for important occasions and a smaller one to receive guests. The house has two kitchens—a small one used in the summer and a larger one for winter when all the family lived in one room that was kept warm during the cold winter. This kitchen and its adjoining rooms have several grain bins beneath the wooden floor boards, as the family stored grains for themselves as well as for other families in Leh. In 1984, the family left their house to build a new one in Fort Road, where their fields were located. The house, along with the adjoining Gyaoo House (residence of artisans to the king) was restored from 2005 to 2009 and is now used as a community arts and media space (Figure 28).

Lonpo House

The Lonpo family was arguably the most powerful of all the ministers under the king, as their residence lies immediately below Leh Palace and above all the other houses (Figure 29). It has a spacious room on the terrace and a kitchen and a guest room on the floor below. The house existed before Leh became an important centre with the construction of Leh Palace in the early seventeenth century. The last Leh Lonpo was a legendary figure known for his aristocratic physical stature; he was also a keen dancer and used to lead the Kathog Chenmo performance, a special dance by aristocrats during Dosmochey, Losar ceremony or royal marriages at the palace.

After the demise of the last Lonpo, the house was inherited by the Kalon family of Changspa. They in turn offered it to Chemday Monastery and it was used by their monks. From 2000 to 2003, it was restored by conservation architect John Harrison. The house continues to be used by the monks of Chemday Monastery, and a room has been let out to the Himalayan Cultural and Heritage Foundation (HCHF).

Shangara House

This is one of the bigger houses in Old Town, known for its large Chodkhang (prayer room). Apart from the prayer room and a kitchen, there is a beautiful balcony with intricate woodwork that faces the Leh Bazaar (Figure 30). The descendants of this family were key members of the Lopchak Mission, leading it in turns along with the Kalon, Khwaja and Radhu families. Lopchak was a biannual trade mission that went to Lhasa on behalf of the Ladakhi king, bearing items of trade as well as gifts for the Dalai Lama. In return Lhasa sent the Chaba which primarily brought brick tea to Ladakh amongst other items of trade.

Qadir Sheikh House

Located directly behind the Jama Masjid, this house has an exquisitely carved wooden balcony. Once it was famous for a small room perched above the mosque with the Chutey Rantak pond below, looking as if it were suspended mid-air (Figure 31). This room was dismantled some years ago. The winter kitchen of the house was so large it could hold roughly 100 people. The grandson of Qadir Sheikh remembers, especially during the Dosmoche festival, many people coming to the house in the evening, and dancing and singing. One of his great grandfathers wrote the famous folk song titled ‘Rholtak Ringmo’. Sheikh Ghulam Rasul, the last owner to live in the house, had a small shop where he repaired a range of items from torches, radios and even broken teeth. This innovative man also created a pulley to lift water to his house from the Chutey Rantak pond. Rasul belonged to the Skara village and was from a Buddhist family called Sasoma; this was before he married a Muslim woman and converted to Islam. The Rasuls moved out in 2008 leaving behind Ghulam’s name which he had inscribed on the ‘foundation plate’ of the town’s Jama Masjid.

Kalmak House

Kalmak House is located behind the Jama Masjid, sandwiched between the Onpo and the Shangara House (Figure 32). The walls of the house are in distinct blue colour. The family’s descendants were from Central Asia, and the house was at one time called ‘China-Pa’ (‘man from China’). The king gave them the title of Takshos-pa. Originally, the family was Buddhist—the owners’ name in the revenue record of 1908 is registered as Gatuk, son of a person called, Ishay. Revenue papers also mention one of the owners as a Tsewang (a Buddhist name) and the house also had a Buddhist chapel. When the daughter of the family Abhi Khanoom converted to Islam, she gave away the ritual books and objects in the chapel to the Gog-sum Pa (the people of Gog-sum). The family used to host travellers and traders from Kargil for a long time.

Old Town Today

In 1834, soon after the Dogra invasion of Ladakh, the royal family vacated their palace in Leh and moved to their residence in Stok where they reside till date. The wall and the gates surrounding the town were gradually brought down. With the departure of the royal family from the palace, the grandeur and importance of the place diminished. Residents of the area followed them, most moving to the lower parts of Leh town where they owned land. With their movement out of Old Town, a slow and steady deterioration of the neighbourhood took place; homes lay neglected—some demolished while others are almost in ruins (Figure 33). In 2008, the town was declared an endangered site and added to the World Monuments Watch list.

The town still lacks sensitive infrastructure development. While modern amenities have been provided in the area, they have been introduced without taking into account the terrain of the land and heritage value of the town. The problems in this area are numerous including lack of sustainable drainage and disposal of waste, unreliable water and electricity supply, proliferation of garbage leading to unhygienic conditions, and open spaces being used as toilets (Figure 34). There are no proper pathways in the area and the town also lacks street lighting (Figure 35). In addition, there are inadequate public spaces for the community, especially children.

Fig. 34. Sewage and drainage problems seen in the street of Manekhang, in Old Town. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2011; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Fig. 35. Woman trying to walk down a path from Zpya Café, in the old town of Leh. Photograph by Tashi Morup, 2011; courtesy LAMO Visual Archive.

Electricity first came into this area in the 1970s, but electric poles have not been positioned with any kind of consideration for their placement with respect to houses and pathways. It is the same with pipes that bring water into the area. Although public taps arrived in the 1980s, the pipes have been haphazardly laid—some of them right across pathways making it extremely difficult to walk, especially at night in the absence of street lighting. Some water connections have come up right next to soak pits where dogs and cows are often seen scrounging for food, making it unhygienic and open to diseases. In the absence of regulations for disposal of kitchen waste, the waste is often thrown on pathways which encourages more street dogs in the area. Open sewers were built in 2002–03, and these are too shallow which leads to overspills on the pathways. At other times, drinking water pipelines run too close to them or right through them. And there are times when the sewers get blocked with garbage. Open defecation is one of the biggest problems—as lack of sanitation facilities not only affect the visitors but also the residents who often have to make do with rented houses that lack toilets and washing facilities. In the absence of an efficient process for garbage collection and public containers for disposal; trash is strewn across the pathways, dumped into the sewers and on the ruins of former houses.

While a few of the historical houses in this area have been restored, others have either fallen to ruins or have been demolished to make way for cement and concrete structures. Many of the original owners no longer reside in their homes; some have rented their houses out and there are others still who have let their homes disintegrate. Thus, due to cheap rates of accommodation, the town has become home to many migrant workers. However, tenants live in crowded rooms without basic amenities.

A lack of proper infrastructure has prevented the old town of Leh from coping with the developments taking place around it, making it harder to realise its full potential as an important heritage area for Ladakh. This also blocks its tourism potential as an important heritage precinct which could have economic benefits for the community that resides here. What was once the pride of Leh town—the heart of its political, economic and cultural kingdom—has now been reduced to a squalid settlement.

Notes

[1] Personal communication, Dr Phuntsog Angchuk Munshi, Tashi Morup, January 31, 2018.

[2] What is today known as Fort Road and Old Fort Road.

[3] ‘Land Holding Settlement (Bandobasti Khewat ) of 1908.’ Revenue Record. Leh: Tehsil Office, Urdu.

[4] 1 kanal equals 505.857 square metres.

[5] The two stupas are said to have been built by Sengge Namgyal but there is no documentation to confirm this.

[6] Gyal Khatun, King Jamyang Namgyal’s wife and Sengge Namgyal’s mother, is said to have had a small mosque for her own personal use just below the palace. Built in the sixteenth century, the mosque no longer exists (Sheikh 2005: 37).

[7] Guru Nanak is the founder of the Sikh faith.

[8] Togoche, according to Dr. Phuntsog Angchuk Munshi, means ‘tax collector’, and was not the family house name. The Munshi retained this function after the Dogra occupation. In the later nineteenth century Munshi Palgyas was the Keshar, the treasurer for Ladakh, operating from the Munshi House as there was no separate treasury. The ‘treasury’ may have been the stone storeroom next to the summer kitchen in the Munshi house (Harrison 2017: 22).

References

Harrison, John. 2017. The LAMO Centre: Restoration and Adaptative Reuse in Leh Old Town. Leh: The LAMO Trust.

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani. 2005. ‘Islamic Architecture in Ladakh.’ In Ladakh: Culture at the Crossroads, edited by Monisha Ahmed and Clare Harris, 34–43. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Bibliography

Bray, John and Tsering D. Gonkatsang. ‘Three 19th Century Documents From Tibet and the Lo Phyag Mission From Leh to Lhasa.’ Rivista Studia Orientali Supplemento, no. 2 (2009): 97–116.

Cunningham, Alexander. Ladák: Physical, Statistical and Historical: With Notices of the Surrounding Countries. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 2005.

Jest, Corneille and John Sanday. ‘The Palace of Leh in Ladakh: an Example of Himalayan Architecture in Need of Preservation.’ Mountain Research and Development 3, no. 1 (1983): 1–11.

Kimura, Megumi. ‘Past forward: Understanding Change in Old Leh Town, Ladakh, North India.’ MA thesis, Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, 2013.

Leh: Ladakh Arts and Media Organization. ‘The Survey of Old Town.’ LAMO Papers (2011-2012).

———. ‘Old Town Leh Neighbourhood Study Project’. Unpublished Papers.

J&K Revenue Department. Land Holding Settlement (Bandobasti Khewat) of 1908. Revenue Record. Leh: Tehsil Office.

Li, Kuang-Han. 2004. ‘Conservation of Vernacular Ladakhi Architecture: The Munshi House in Old Town Leh, Ladakh.’ Unpublished MA thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

LAMO and LATO. Rajiv Awas Yojna—Pilot DPR. 2013. Research conducted by LAMO and LOTI. Leh: Municipality, Leh & Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council.

Rizvi, Janet. 1999. Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.