A man of many firsts, Khemchand Prakash’s unparalleled contribution to the music of Hindi film industry pioneered a legacy that should never be forgotten. We train the spotlight on the life and work of the musical genius ‘whose contribution to Hindi film music was far greater than just the songs he composed’. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

Hindi film music aficionados are familiar with the story of Lata Mangeshkar and Kishore Kumar’s first meeting on their way to the recording studio Bombay Talkies, where Mangeshkar thought she was being stalked by Kumar.[1] The two singers were on their way to record their first duet, ‘Ye Kaun Aaya Re’ from the film Ziddi (1948), at the same time which led to the confusion. Incidentally, Ziddi, besides being dubbed as Dev Anand’s big break, also marked Kishore Kumar’s debut with his solo song, ‘Marne Ki Duayen Kyon Mangu’.

The man responsible for bringing the two singers together—clearly a watershed moment in the history of Hindi film music—was Khemchand Prakash, a celebrated music director of the 1940s and early 1950s.

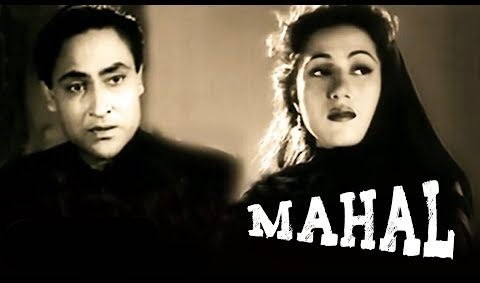

A forgotten legacy, Khemchand Prakash, besides launching the careers of Lata Mangeshkar and Kishore Kumar, mentored artistes such as Manna Dey, Mukesh, Mohammad Rafi and Naushad sa’ab, among others. Working with the top stars of the time, including K.L. Saigal, Kamini Kaushal, Noorjehan, Shamshad Begum and Ashok Kumar, making them, literally, sing and dance to his tune, Prakash died due to liver cirrhosis in his early ’40s just months before the release of Mahal (1949), which had the haunting melody of ‘Aayega Aanewala’ sung by Mangeshkar that catapulted her to fame.

In his short but illustrious career in Hindi films, Prakash successfully steered the musical journeys of several Hindi film singers. So powerful was his composition in Mahal that HMV had to include Lata Mangeshkar’s name as part of its credits on the records after All India Radio was inundated by listeners to name the singer.[2] This gave an impetus to the ongoing fight by playback singers to give them ‘singer credits’.

Also read | Mubarak Begum: Bollywood Music's Shooting Star

Interestingly, the echo effect of the iconic Mahal song, according to a Filmfare report, was brought out by Prakash getting Mangeshkar to slowly walk from the recording booth’s door towards the mic in the centre of the room.[3] Another important contribution of Prakash was that he used not just Hindustani classical music elements in films (he was a trained classical vocalist and a kathak dancer) but also became ‘one of the first [music directors] to use piano and clarinet in his song settings’, explains John Caldwell quoting Ashok D. Ranade’s book, Hindi Film Song: Music Beyond Boundaries. Author Ganesh Anantharaman describes Prakash as the ‘man whose contribution to Hindi film music was far greater than just the songs he composed’.[4]

The Beginnings

According to Dr Vidya Arya, who completed her thesis on the music director after three years of intensive research, which included meeting luminaries of the film industry such as Kamal Amrohi, Manna Dey, Naushad, among others, Prakash was born in Jaipur (not Sujangarh, as many websites suggest) on December 12, 1907, in a culturally rich household. His father, Pandit Govardhan Prasad was a well-known Dhrupad exponent and a kathak dancer.

The Years of Struggle

Regarded as a child prodigy, Prakash began performing in the royal courts of Rajasthan as a young boy, before moving to Nepal in his late teens to become a royal court singer at the invitation of the then king of Nepal who was impressed with his singing style. For the next seven years, Prakash remained in Nepal before leaving the royal court to begin an independent career as a music director in Calcutta.

The days in Calcutta, despite Prakash’s musical prowess, were rife with challenges. Though he became an artiste with All India Radio, money was hard to come by and it was only when Timir Baran, music director of Devdas (1935), starring K.L. Saigal, offered him a role as an assistant that Prakash’s career received an uptick before getting its brief but stupendous success.

Success in Bombay

Prakash arrived from Calcutta to Bombay in the late 1930s. ‘It was a time when his friends such as Prithviraj Kapoor and Ashok Kumar were shifting or had already shifted to Bombay. They were all newcomers then, all wanting to try their luck in films,’ explains Arya.

In Bombay, the late Naushad sa’ab worked as Prakash’s music assistant on his first film as an independent music director Gazi Salauudin (1939), made under the banner of Supreme Pictures. In a documentary celebrating Prakash’s birth centenary, Naushad said that his mentor’s method of using ragas in film music influenced him greatly. Given his background as a trained Dhrupad singer and kathak dancer, his sense of rhythm—as evident in many of his compositions—is undoubtedly outstanding. Tansen (1943) bears evidence of this mastery.

Also read | Mani Kaul: The First Rebel of Indian Parallel Cinema

According to Ashok Raaj, author of Hero: The Silent Era to Dilip Kumar (Volume 1), Tansen was one of the greatest musicals of the film industry, which paved the way for other musicals such as Baiju Bawra (1952), Basant Bahar (1956), Sangeet Samrat Tansen (1959), Rani Roopmati (1960), and Meera (1979). Similarly, ‘Aayega Aanewala’ worked as a signature tune throughout the film and a similar trend was seen in later thrillers such as Madhumati, Woh Kaun Thi, and Mera Saaya.

‘While his contribution is unparalleled, who knows how else he would have steered the Hindi film music genre if he hadn’t died so suddenly,’ wonders Shamsuddin Snehi, a resident of Sujangarh who, along with other members of a local NGO Marudesh Sansthan, is trying to convince the government to allot some land to honour the late music director. ‘I fear that the memory of his contribution is slowly fading away with the passage of time,’ says Snehi.

Gone Too Soon

In less than a decade of working as a solo music director, Prakash worked on close to 40 films and had a massive success rate. Towards the end, he was working on three films and it is believed that Manna Dey who was closely working with the music director then eventually found a way to complete the films.

Sadly, Prakash’s family faded into oblivion with lyricist Javed Akhtar even commenting some years ago in parliament that his wife was found begging years after his death when, ironically, money worth INR 50 lakh was owed in royalty to him for ‘Aayega Aanewala’.

A Pick of Prakash's Top Five Hits

‘Kookat koeliya kunjan mein’ from Bhartrihari (1944): Also used innovatively in a scene in Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala (1985) where it is heard on an old gramophone

‘Diya Jalao Jagmag, Jagmag’ from Tansen (1943)

‘Ye Kaun Aaya Re’ from Ziddi (1948)

‘Aayega Aanewala’ from Mahal (1949)

‘Aati Hai Yaad Humko Janvary Farvary’ from Muqaddar (1950): One of the first few duets of Asha Bhosle and Kishore Kumar

This content has been created as part of a project partnered with Royal Rajasthan Foundation, the social impact arm of Rajasthan Royals, to document the cultural heritage of the state of Rajasthan.

This article was also published on South Asia Monitor.

Notes

[1] Nasreen Munni Kabir, ‘In Lataji’s Own Voice’, Mumbai Mirror, October 4, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/others/sunday-read/in-latajis-own-voice/articleshow/78466943.cms

[2] Poonam Saxena, ‘The Way We Were: Lata and the dawn of the playback era’, The Hindustan Times, August 16, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.hindustantimes.com/art-and-culture/the-way-we-were-lata-and-the-dawn-of-the-playback-era/story-OyUByvcmCYpeY2nd3agzUP.html

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ganesh Anantharaman, Bollywood Melodies: A History of the Hindi Film Song (New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2008).