Patuas, the itinerant performers of the folk art of patachitra, went from village to village with illustrated pats (scrolls) made of handmade paper; their performance involved reading out their hand-drawn religious narratives interspersed with songs to a patient rural audience.[1] The first mention of such a travelling group of performers can be found in a thirteenth-century Sanskit text Brahma Vaivarta Purana.[2]

In the early nineteenth century, when Calcutta was slowly becoming the epicentre of trade and commerce with a strong British presence, the city attracted a conglomeration of folk artists of different cultures and professions, all looking for opportunity in the growing economy the city provided.[3] Patuas followed suit, settling in the area around the Kali temple called Kalighat, the spiritual centre of Calcutta. Once performance artists who survived on donations, in their new environment, divorced from their itinerant life, the patuas became painters who sold their work for money. However, the transition did not happen without modifications and adaptations; instead of traditional scrolls, the Kalighat painters started painting on single panels made of cloth or handmade paper, before shifting to cheap factory-made paper as time progressed. The new medium, easier to carry, soon made Kalighat paintings a favourite souvenir for tourists and pilgrims to the Kali temple. Their popularity soared in the 1830s, and they were very much in vogue until the 1930s.[4]

Mythology and Religion

In villages, the patachitra form was creating a dynamic oral tradition, aided by visual art. The subjects of the scrolls were mostly religious in nature where both Hindu and Muslim tales were depicted, the most famous being parts of Ramayana and stories on the lives of popular Islamic saints.[5] According to art historian Atul Chandra Bhowmick, the two religions illustrated on paper expressed themselves in patua lives and cultures as well, with rural Bengal being influenced by the influx of Islamic armies from the western part of the subcontinent as early as the twelfth century.[6]

When the patuas moved to the urban setting, they painted the pats from the perspective of souvenirs, focussing on mythological and religious figures. Pats with Hindu gods and goddesses, scenes from Ramayana and Mahabharata, and Kali, of course, found favour among their working-class patrons.[7] Shiva in the form of Panchanan (five headed) or sitting with Parvati on Nandi was a popular painting, as was Lakshmi and her various avatars; other oft-painted deities included Durga as Mahishasur Mardani (slayer of the demon, Mahishasur), Kartikeya, Ganesha, and Saraswati. Different incarnations of Vishnu as Parashurama, Balarama, Krishna, Rama, and a series of scenes from the life of Krishna showing him milking a cow, killing the demoness Putana, his love affair with Radha, Kaliya daman (subjugation of the serpent, Kaliya) were all part of the Kalighat repository.[8]

Keeping with Kalighat painting’s cosmopolitan nature which helped its spread, the illustrations also included Islamic and Christian iconography. Historians A.N. Sarkar and C. Mackay attest, ‘It is important to note the presence of strong images from Islam and Christianity in the Kalighat repertoire. The painters sought to capture all slices of the truly cosmopolitan market available to them.’[9] The Bodleian Library in UK, for example, has a painting made in 1875 that shows a carnival float in the form of a Buraq (an anthropomorphic figure in Islamic literature), on which Prophet Muhammad flew to heaven, signifying the Muslim holy day of Muharram; another famous representation is of the horse called Duldul on which Hussain, the younger grandson of the Prophet, was killed at Karbala.[10]

Influences on the Art

From the mid-nineteenth century, the themes of Kalighat paintings began to change from religious to relatable, humorous and contemporary. They started reflecting and critiquing the urban society, the rich Bengali aristocracy, and their British lifestyle. ‘Events of burning interest, social oddities and idiosyncrasies, follies and foibles of people, and hypocrisies and meanness—these never escaped the Kalighat painters.’[11]

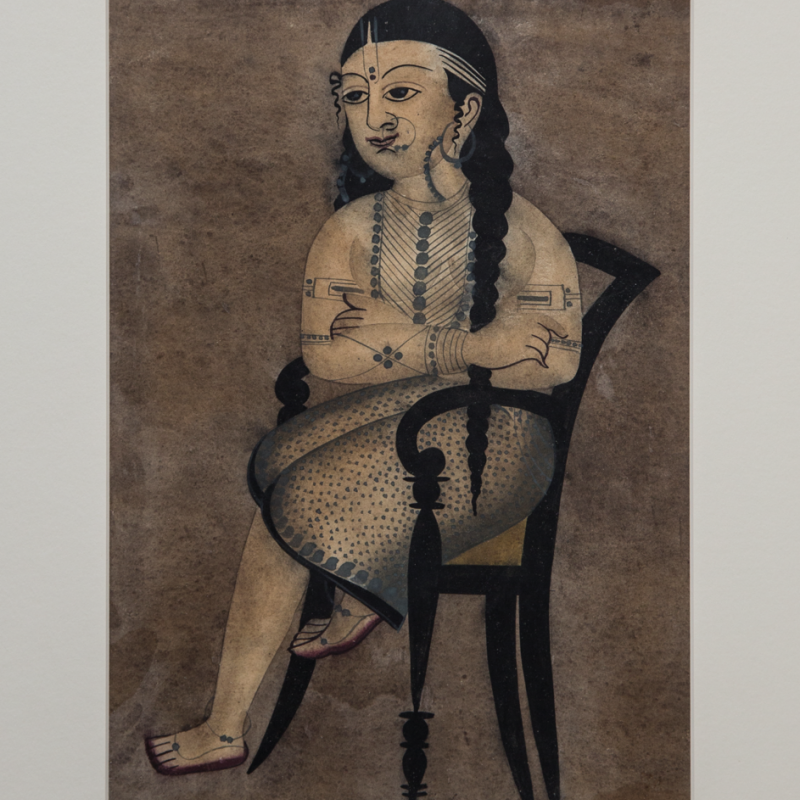

The Kalighat paintings tapped into the working class’s disdain for the babus who were close to the English elites and tried to ape their way of living.[12] Dhoti-clad babus with oiled hair, carousing with courtesans, smoking a hukkah, drinking and chewing paan (betel leaf), were often cast as embodiments of moral decay as historian Mukul Dey writes, ‘…wealthy zeminders spending their money on wine and women, foppish babus spending their day and night at nasty places…they would draw the caricatures in such a way as would repel ordinary people from such activities.’[13] Among the other favourites of the Kalighat painters were the corrupt Brahmin, who would take bribes and seduce women; courtesans; and the bibi, the female equivalent of the babu. In Kalighat paintings, bibis were often seen dominating their husbands, ‘submissive babu’[14], and chastising them for their immoral behaviour. The painting of the courtesan in goddess-like postures was an interesting deviation from the Victorian morality that saw them as women of questionable character; they were often shown seated in a Goddess Saraswati-like pose with a violin.

As Kalighat painters functioned amidst influences of various cultures, their paintings too melded the East and the West and the traditional and contemporary. Prime examples of these assimilations are paintings of Ram and Lakshman sporting Prince Albert hairstyles, Yashoda and Krishna engaged in household chores, and Kartikeya wearing buckled shoes with a shawl draped over his shoulder.[15]

Kalighat painters did not follow any set rules of theories of art, their painting mostly evolved with their interactions with the surroundings; however, they did borrow styles and techniques from Mughal miniatures and Ajanta paintings[16] in their depictions of animals and birds in the pats. The animals that found place in Kalighat paintings include birds, fish, cats, crustaceans, tigers and lions. The animals often were drawn as part of visual stories of popular Bengali proverbs; some pats also showed animals and birds with human subjects, for example, a bird perched on a tonsured Vaishnava man’s head. There were also paintings of hunting scenes, like the one in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection that shows a European man sitting on an elephant and shooting at a tiger; this reflects the local and colonised life the patuas saw from the Kalighat area. The animal paintings were also, at times, used to satirise the elite Indian classes; for example, a popular painting of a cat with a fish in its mouth satirises the vegetarian Hindu priest who would indulge in consuming meat in private.

The Country’s News Bureaus

Dey calls the Kalighat painters ‘news bureaus of the country’.[17] Gradually, as they adapted to the contemporary urban culture, the Kalighat painters started painting news stories doing the rounds in Calcutta. Among the highly valued pats with illustrations of news events were the ones depicting the gruesome Tarakeshwar murder case of 1873, where a woman was killed by her husband for having an affair with a priest, and the painting of the yogi Shyamakanta Banerjee wrestling a tiger.[18]

As they painted at the height of the nationalist movement in India, there were also illustrations of freedom fighters, particularly Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi, that were popular among the patrons. By painting topical news, patuas adapted folk art, which made them contemporary as well as socially relevant in the Calcutta of the 1830s to 1930s.[19]

National Identity and Jamini Roy

After the patuas lost patronage in about 1930[20], they began to look for other means of livelihood. As cheap lithographs flooded the market, many of the painters were forced to move back to rural settings and change vocations.

While Kalighat paintings went off the market, they left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of India. There was a time when government-funded art schools, influenced by orientalist thinkers such as James Mill, believed Indian artists did not know the ‘the language of art’ which required ‘exercise of intellect’, and, at best, they could copy[21]. However, things started to change as India’s fight for freedom took precedence with initiatives such as the Swadeshi movement, which promoted preservation of folk art as cultural ideals.[22] Many artists broke the shackles of Western thinking and looked for indigenous resources to find a new language of art, among them was Jamini Roy who summarily rejected the teachings he received at the Government School of Art in Calcutta.[23] Artists like Roy turned to Kalighat paintings for stylistic influence and were richly rewarded by its unique and vast repertoire.

As with other indigenous art forms, Kalighat painting offered traditional authenticity in the country’s struggle for a national identity. They provided a foundation that could then be modified and updated to express a shared sentiment of nationalist pride.[24]

Notes

[1] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings.

[2] Chatterjee, From the Karkhana to the Studio.

[3] Winchester, Simon Winchester’s Calcutta.

[4] Ghosh, ‘Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century Calcutta in Maxwell Sommerville’s Ethnological East Indian Collection.’

[5] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings.

[6] Bhowmick, ‘Bengal Pats and Patuas.’

[7] Slaughter, ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings.’

[8] Sanyal, ‘Kalighat Paintings.’

[9] Sarkar and MacKay, ‘Kalighat Paintings.’

[10] Sanyal, ‘Kalighat Paintings.’

[11] Dey, ‘The Painters of Kalighat.’

[12] Gupta, ‘Baboos, Bibis and Bhadramahila.’

[13] Dey, ‘Drawings and Paintings of Kalighat.’

[14] Bhattacharya, ‘The Popular and the Nation.’

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings.

[17] Dey, ‘Drawings and Paintings of Kalighat.’

[18] Sarkar and Mackay, ‘Kalighat Paintings.’

[19] Jefferson, ‘The Art of Survival.’

[20] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings.

[21] Chatterjee, From the Karkhana to the Studio.

[22] Das Gupta, ‘In Pursuit of a Different Freedom.’

[23] Chatterjee, From the Karkhana to the Studio.

[24] Slaughter, ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings.’

Bibliography

Bhattacharya, Arunima. ‘The Popular and the Nation: The Kalighat Patas.’ The Criterion: An International Journal in English 4, no. 2 (April 2013): 1–9.

Bhowmick, Atul Chandra. ‘Bengal Pats and Patuas: A Case Study.’ Indian Anthropologist 25, no. 1 (1995): 39–46

Chatterjee, Ratnaboli. From the Karkhana to the Studio: Changing Social Roles of Patrons and Artists in Bengal. New Delhi: Books & Books, 1990.

Das Gupta, Uma. ‘In Pursuit of a Different Freedom: Tagore’s world university at Santiniketan.’ India International Centre Quarterly 29, no. 3/4 (2002): 25–38.

Dey, Mukul. ‘Drawings and Paintings of Kalighat.’ Advance, Calcutta, 1932. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.chitralekha.org/articles/mukul-dey/drawings-and-paintings-kalighat#.

———. ‘The Painters of Kalighat: 19th Century Relics of a Once Flourishing Indian Folk Art Industry Killed by Western Mass Production Methods.’ The Statesman, Calcutta, October 22, 1933. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.chitralekha.org/articles/mukul-dey/painters-kalighat-19th-century-relics-once-flourishing-indian-folk-art-industry-k.

Ghosh, Pika. ‘Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century Calcutta in Maxwell Sommerville’s Ethnological East Indian Collection.’ Expedition 42, no. 3 (2000): 11–21.

Gupta, R.P. ‘Baboos, Bibis and Bhadramahila.’ In Naari: A Tribute to the Women of Calcutta, 1690–1990. Calcutta: Ladies Study Group, 1990.

Jefferson, Pilar. ‘The Art of Survival: Bengali Pats, Patuas and the Evolution of Folk Art in India.’ Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2014. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2837&context=isp_collection

Sanyal, Partha. ‘Kalighat Paintings: A Review.’ Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design 3, no. 1 (2013): 2–9.

Sarkar, A.N., and C. Mackay. ‘Kalighat Paintings.’ In National Museums and Galleries of Wales. New Delhi: Roli Books and Lusture Press, 2000.

Sinha, Suhasini, and C. Panda. Kalighat Paintings: Images from a Changing World. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2011.

Slaughter, Lauren M. ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings.’ Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research, School of Humanities and Social Sciences 11 (2012): 242–258.

Winchester, Simon. Simon Winchester’s Calcutta. Footscray, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet Publications, 2004.