Rural Bengal has had an intimate relationship with the art of storytelling. Travelling folk painters would go from village to village to regale locals with narrative stories on handmade cloth scrolls known as patachitra. The first mention of such a group appears in Brahma Vaivarta Purana, a thirteenth-century Sanskrit text.[1] Each section of the scroll was called a pat, hence the people who read out from them came to be called patuas. These performers would slowly unroll the scroll, one section at a time, and then sing and perform the depicted story. Most of their subjects were religious in nature and they illustrated both Hindu and Muslim tales, the most famous being parts of Ramayana and the lives of popular Islamic saints.[2] The patuas did not sell the artworks or scrolls; they made their living from donations.[3]

Moving to the City: From Entertainers to Sellers of Art

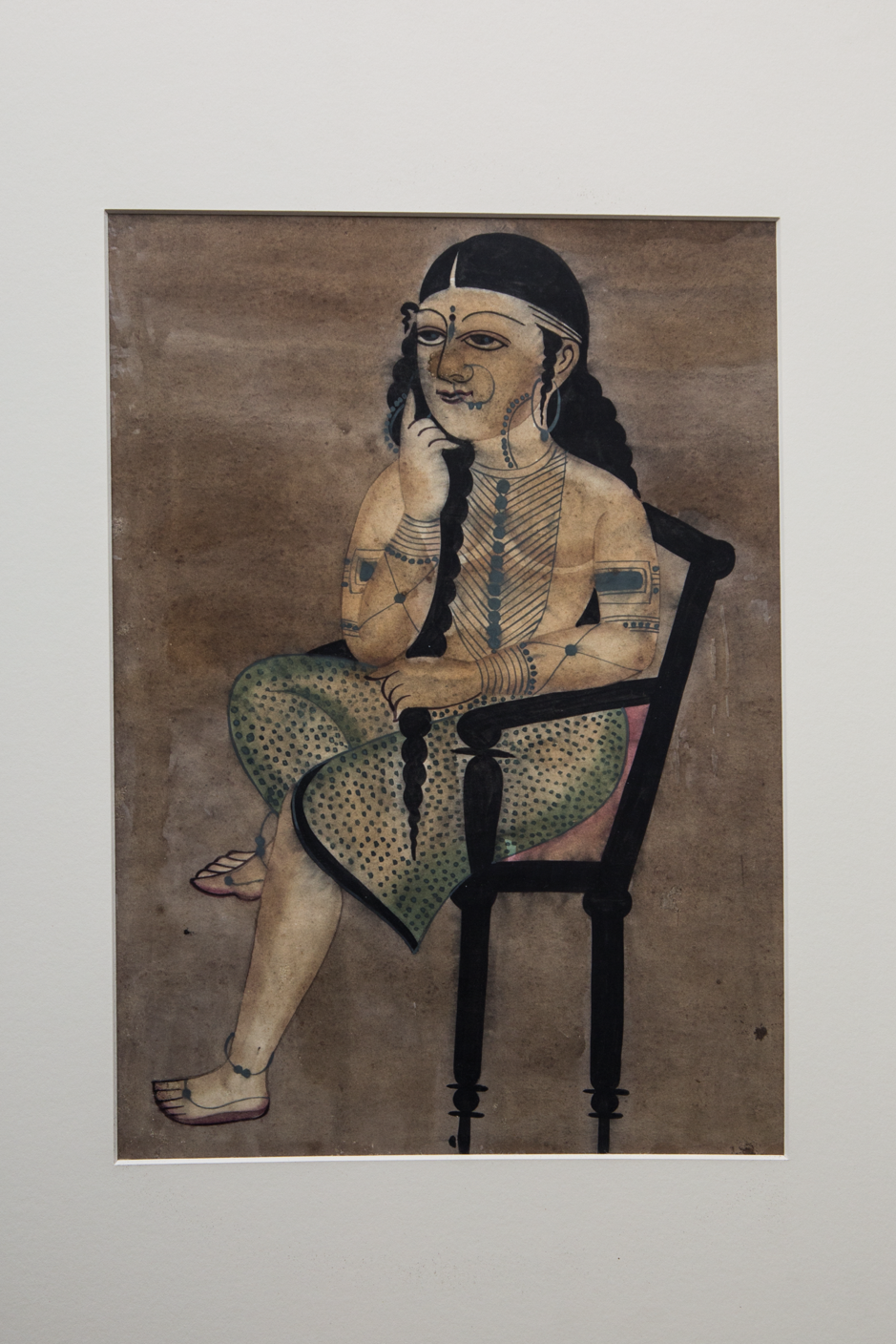

In the mid-eighteenth century, many of these patuas along with other skilled artists from rural Bengal, especially from 24 Parganas and Midnapore, migrated to Calcutta, a key destination for immigrants searching for economic opportunities. Calcutta at that time was rapidly expanding due to commerce generated by the British and other European settlers who lived in the southern part of the city. The patuas set up stalls outside the Kali temple (established in 1798), on the ghat of the Buriganga (a canal diverging from the Ganges river) in south Calcutta, from where, since the 1830s to the 1930s, they sold pilgrimage and tourist souvenirs[4], which, because of the location, came to be known as Kalighat paintings.

For these Kalighat painters, there was a complete shift in perspective from their rural days: firstly, they no more had to travel to audiences, as tourists and pilgrims now came to them; secondly, their business model changed from that of entertainers to sellers of physical copies of their work. Since scrolls were ineffective at this juncture, these painters began to sell individual panels and paintings of solitary gods and goddesses, like chouko (square) pats. Later, the introduction of cheap factory-produced folio paper from British missionaries’ printing presses as well as watercolour imported from Europe saved Kalighat painters time and energy that earlier went into the use of the traditional medium of cloth.[5]

The market for such Kalighat paintings rapidly increased in the nineteenth century—not just pilgrims from among the working classes but also merchants from different parts of India as well as European travellers, administrators and collectors such as Sir Monier Monier-Williams and John Lockwood Kipling, whose collections are now housed in the Bodleian Library and Victoria and Albert Museum, respectively.[6]

Production Style and Influences: Was Kalighat Painting a Western Art?

These Kalighat paintings owed its popularity to the efficiency and skill in its production, which was a collaborative family effort, resembling an assembly line production process. According to painter-engraver Mukul Dey,[7] the method of drawing was very simple:

One artist would in the beginning, copy in pencil the outline from an original model sketch, another would do the modelling, depicting the flesh and muscles in lighter and darker shades. Then a third member of the family would put in the proper colours of the different parts of the body and the background, and last of all the outlines and finish would be done in lamp black.

Even brushes used were made of simple goat’s tail or squirrel’s hair. One of the first descriptions of Kalighat paintings was by art collector Ajit Ghose:

The drawing is made with one long bold sweep of the brush in which not the faintest suspicion of even a momentary indecision, not the slightest tremor, can be detected. Often the line takes in the whole figure in such a way that it defies you to say where the artist’s brush first touched the paper or where it finished its work…[8]

Traditionally, before the shift towards factory-made watercolour, all patua paints were handmade from naturally occurring sources such as indigo, turmeric and other plants.[9] The dyes and extracts were made into paints by mixing a variety of binding agents which included the natural gum of bel (wood apple) and crushed tamarind seeds, and colloidal tin was used to embellish paintings and replicate the surface effects of jewels and pearls.

There is much debate about the Kalighat style of paintings: is it a Europe-influenced form or truly indigenous? Art historian and curator W.G. Archer in his famous book, Bazaar Paintings of Calcutta: The Style of Kalighat (1953), sums up a general consensus that Kalighat paintings reflect a Western influence on immigrant patuas. This discourse stems from a notion of Orientalism, proposed and readily accepted by scholars during the formative years of the British regime. The belief in a past Indian golden age coincided with Eurocentric views that strongly favoured Western art over traditional Indian ones. This perception immediately devalued traditional Indian art and values, including the emergence of the new Kalighat style of painting.[10] Archer, the main proponent of the British influence view, attributes his reasoning to the use of folio-sized paper instead of the traditional cloth; use of watercolour on a blank background to keep the focus solely on the central figure; use of shading in the pictures which art historian Jyotindra Jain much later describes as a sort of bold chiaroscuro and the beginning of highlighting the three dimensions of figures[11]; the urban themes and subjects selected and painted by the artists; and finally, some artists who signed their pats, keeping with a more Western concept of authorship.

Ghose, one of the first advocates of ‘truly indigenous Kalighat style’ was refuted by Archer, who maintained that the style of art was a by-product of British colonial influence:

Such a school, at once so Indian and yet so modern, compels us to face some unexpected facts, for, despite its marked dissimilarity from British art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the style was actually a by-product of the British connection and can only be understood against the background.[12]

Archer based his evidence on the fact that in the late eighteenth century Calcutta’s bazaars were found to be selling British oil paintings and watercolours, after European art went for sale because the ‘high British death-rate and constant movement of British personnel resulted in frequent sales of gentlemen’s effects’[13]. It was only after European paintings reached the bazaar that Kalighat painters adopted watercolours, shading and blank backgrounds, he says.

However, this is purely speculative. Archer argued that the blank background was influenced by British natural history paintings—he cited examples from the Wellesley folio of plants and animals—but from a mass production standpoint, it could have just been easier for Kalighat painters to keep the background blank.[14] Besides, plain and unprimed backgrounds had even been seen in the seventeenth-century Bhagavata manuscript and the eighteenth-century Ramacharitamanas manuscript, and other scroll paintings predating colonial rule[15], which also included Rajput artworks. The growing need to produce large number of paintings quickly and cheaply facilitated the switch to paper from cloth as well as the switch from a scroll-narrative formula to a single-page format.[16]

The use of watercolours is not something new, claims historian B.N. Mukherjee.[17] He says the Kalighat painters had always made their own colours, and water was used to dilute indigenously made paint. Kalighat paintings have a sense of vibrancy and opaqueness unlike the translucency of a British natural history painting or Company paintings which were made by Indian artists commissioned by the British East India Company using European techniques. The context of shading that Archer mentions had been first countered by cultural historian Sumanta Banerjee, who stated that many of these painters had an idea of shading because they painted clay figurines of deities.[18] Thus, the understanding of three-dimensional forms transferred from clay modelling to paper at Kalighat.[19]

The lack of contact between the Kalighat painters and the British casts further doubt on Archer’s hypothesis. While the Indian upper and middle class enjoyed limited social acceptance by the British within the realm of careers that embraced Eurocentric values, it is unlikely that the Kalighat painters had any direct contact with the ruling classes.[20] The Kalighat painters were very much outsiders, and their popular art style was one of the first instances where anyone called visual attention to the deteriorating effects of British presence on traditional Indian culture.[21] Archer’s insistence on Western influence on Kalighat paintings is further weakened by flaws in his methodology. For example, the signed pats in his possession were personally collected by him from a particular Kalighat painter; otherwise, the number of signed pats is too small compared to the anonymously made large body of paintings.[22]

While Archer’s concept subsequently effected scholars who kept with his views, and, later, coined the style to be Anglo-Indian, many scholars refuted this claim. Art historians A.N. Sarkar and C. MacKay, for instance, say, ‘The Kalighat school of painting is perhaps the first school of painting in India that is truly modern as well as popular. With their bold simplifications, strong lines, vibrant colours and visual rhythm, these paintings have a surprising affinity to modern art.’[23] Historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta claims that the Kalighat style should be celebrated as authentically Indian as the artists thrived in a colonial urban setting all the while maintaining traditional imagery and culture, operating under aesthetics inherited from their forebears and modified by themselves.[24]

The Kalighat painters painted satirical humour in an indigenous style while the British were teaching Indians academic art in government-funded art schools. Kalighat art inspired many students to reject the pedagogy of the imperialist art schools and turn to indigenous sources, a prime example of which is the famous painter Jamini Roy. In the twentieth century, when India was struggling to form a national identity, Kalighat paintings acted as a model of authentic and traditional art form, among other indigenous arts and crafts. To emphasise the interactions between Kalighat paintings and anti-colonial struggle, Banerjee evokes the French West Indian political philosopher Frantz Fanon, who states that anti-imperial struggles revitalise the culture and traditions of indigenous classes in colonial settings—as native artists who once used to relate ‘inter episodes’ start bringing them alive with modifications to describe the new sociocultural context, modernising legends, naming heroes and their weapons.[25]

Losing Patronage, Becoming Museum Art: The First ‘Moderns’ of India

Kalighat paintings lost patronage in the early twentieth century, with its final phase being around 1930.[26] Dey, who once called the stalls outside Kalighat temple ‘news bureaus’, lamented in his article: ‘Cheap oleographs of all sorts from Germany and from Bombay now take the field, some of them blatant imitations of Kalighat paintings. These cheap copies have practically killed hand-painted art production as a business and with it the artistic instincts and creative faculty of the painters of Kalighat.’ [27]

The Kalighat painters struggled to cope with the competition of machine-made productions that sold way cheaper than their artworks at two or four pice each, and the subsequent generations were forced to change vocations. For traditional art forms such as Kalighat painting that survive through generational transfer of skills, this was a huge blow. Further, when German traders found that Kalighat paintings were in huge demand throughout India, they brought out cheap imitations in the form of glazed and coloured lithographed copies, which soon replaced the original. Paintings that once ruled the streets became cultural artefacts, as Dey writes, ‘The old art has gone forever; the pictures are now finding their homes in museums and in the collection of a few art lovers.’[28]

While nationalistic tendencies played an important role in Kalighat paintings being referred to as the first ‘Moderns’ today, art historian Pika Ghosh adds that in the early twentieth century, this art form was also validated by the particularised vision of Modernism. Away from the cheapness of just bazaar paintings or travel souvenirs, the Kalighat school was recognised as art when European collectors presented their collections to museums in Europe. It bore the stamp of collective approval. Today, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has the single largest collection of Kalighat paintings which include watercolour drawings, line drawings and hand-coloured lithographs. In Bengal, where the style originated, small collections of Kalighat paintings are at Victoria Memorial Hall, the Indian Museum, Gurusaday Museum and Kala Bhavan in Shantiniketan, among others.

Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff terms the process of transition as ‘singularisation’ in the cultural biography of objects. The elevation in status of Kalighat paintings was not accidental. It coincided with the extinction of the tradition in the 1930s when cheap lithographs overtook hand-painted production. Removed from the general markets, they became rare and, thus, prized possessions.

Notes

[1] Chatterjee, From the Karkhana to the Studio.

[2] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings: Images from a Changing World.

[3] Bose, Patachitra.

[4] Ghosh, Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century.

[5] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Paintings.

[6] Ghosh, Kalighat Paintings.

[7] Dey, ‘The Painters of Kalighat.’

[8] Ghose. ‘Old Bengal Paintings.’

[9] Dutt, Folk Arts and Crafts of Bengal.

[10] Slaughter, ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous style of Kalighat Paintings.’

[11] Tagore, dir., Kalighat Painting.

[12] Archer, Bazaar Paintings of Calcutta.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Slaughter, ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous style of Kalighat Paintings.’

[15] Mukherjee, ‘The Kalighata Style.’

[16] Guha-Thakurta, ‘The Making of a New “Indian” Art.’

[17] Mukherjee, ‘The Kalighata Style—The Theory of British Influence.’

[18] Banerjee, The Parlour and the Streets.

[19] Jain, Kalighat Painting.

[20] Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India.

[21] Slaughter. ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings.’

[22] Guha-Thakurta, ‘The Making of a New “Indian” Art.’

[23] Sarkar and Mackay, ‘Kalighat Paintings.’

[24] Guha-Thakurta, ‘The Making of a New “Indian” Art.’

[25] Banerjee, The Parlour and the Streets.

[26] Sinha and Panda, Kalighat Painting.

[27] Dey, ‘The Painters of Kalighat.’

[28] Ibid.

Bibliography

Archer, WG. Introduction. Bazaar Paintings of Calcutta: The Style of Kalighat. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1953.

Banerjee, Sumanta. The Parlour and the Streets: Elite and Popular Culture in Nineteenth-Century Calcutta. Calcutta: South Asia Books, 1989.

Bhattacharya, Arunima. ‘The Popular and the Nation: The Kalighat Patas.’ The Criterion: An International Journal in English 4, no. 2 (April 2013): 1–9.

Bose, Ratnaboli. ‘Patachitra.’ Daricha Foundation.

Chatterjee, Ratnaboli. From the Karkhana to the Studio: Changing Social Roles of Patrons and Artists in Bengal. New Delhi: Books & Books, 1990.

Dey, Mukul. ‘Drawings and Paintings of Kalighat.’ Advance, Calcutta, 1932. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.chitralekha.org/articles/mukul-dey/drawings-and-paintings-kalighat#.

———. ‘The Painters of Kalighat: 19th Century Relics of a Once Flourishing Indian Folk Art Industry Killed by Western Mass Production Methods.’ The Statesman, Calcutta, October 22, 1933. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.chitralekha.org/articles/mukul-dey/painters-kalighat-19th-century-relics-once-flourishing-indian-folk-art-industry-k.

Dutt, Gurusaday. Folk Arts and Crafts of Bengal: The Collected Papers. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1990.

Ghose, Ajit. ‘Old Bengal Paintings.’ Rupam 27–28 (1926): 98–104.

Ghosh, Pika. ‘Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century Calcutta in Maxwell Sommerville’s Ethnological East Indian Collection.’ Expedition 42, no. 3 (2000): 11–21.

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. The Making of a New “Indian” Art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal, c 1850-1920. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1992.

Gupta, RP. ‘Baboos, Bibis and Bhadramahila.’ In Naari Naari: A Tribute to the Women of Calcutta, 1690–1990. Calcutta: Ladies Study Group, 1990.

Jain, Jyotindra. Kalighat Painting: Images from a Changing World. Middletown: Grantha Corporation, 1999.

Kopytoff, Igor. ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.’ In The Social Life of Things. Edited by Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Mitter, Partha. Art and Nationalism in Colonial India: Occidental Orientations. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Mukherjee, B.N. ‘The Kalighata Style—The Theory of British Influence.’ Indian Museum Bulletin 19 (1984): 7–13.

Phillips, Ruth. After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacement. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Sanyal, Partha. ‘Kalighat Paintings: A Review.’ Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design 3, no. 1 (2013): 2–9. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.chitrolekha.com/V3/n1/02_Kalighat_Paintings.pdf

Sarkar, A.N. and C. Mackay. ‘Kalighat Paintings.’ In National Museums and Galleries of Wales. New Delhi: Roli Books and Lusture Press , 2000.

Sinha, Suhasini, and C. Panda. Kalighat Paintings: Images from a Changing World. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd, 2011.

Slaughter, Lauren M. ‘Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings.’ Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research, School of Humanities and Social Sciences 11 (2012): 242–258.

Tagore, Siddharta, dir. Kalighat Painting. New Delhi: Siddharta Tagore, 2011. DVD.