Moksha is beyond time, beyond space. It means cutting the umbilical cord that connects a person to samsara (material world). Mere death is not moksha; the body perishes but the jiva (soul) is reborn in a new body. For a Jain, attaining moksha is to escape the constant cycle of birth and death, for eternity. Hence, Jainism is also known as mokshamarga (path to liberation).

The quest for moksha is a journey in the metaphysical sense, but it can also be undertaken within a sacred geography. Such journeys of spiritual enlightenment are called tirtha-yatra (journey to a sacred space). A place becomes a tirtha-sthan (sacred space) because of its connection with a jina or tirthankara (Jain ford maker) who may have been born, given sermons or attained moksha at such a place. The physical rigour of a tirtha-yatra is a qualification in the pursuit of moksha, as much as spiritual devotion and earning karmic merit is. Sadhus and yatris (pilgrims) undertake tirtha-yatras throughout the Indian subcontinent, often in remote places and difficult terrains such as mountains. However, tirtha-yatras are not mandatory in Jainism and not all Jains perform them.

One of the major Jain tirtha-yatras (pilgrimages) in Gujarat is the Navanu Yatra (99 yatras), undertaken from Palitana in Bhavnagar district. From Palitana, yatris ascend Shatrunjaya Hill (altitude 580 m), considered to be tirthadhiraja (the king of all yatras), whose summit has hundreds of temples built over several centuries. The objective of the Navanu Yatra is to ascend Shatrunjaya 99 times, hence the name navanu, which is a re-enactment of the number of times Adinatha (the first Jain tirthankara) is believed to have ascended the hill. Jains believe, 23 out of 24 tirthankaras attained moksha on Shatrunjaya Hill, on the summit of which under a banyan tree, Adinatha (locally known as Dada Adishvara) is believed to have given his first sermon. Because of this association, the cynosure of Navanu Yatra is the Adishvara temple (popularly called Dadanu Derashar), where the yatra culminates. Along the way, the yatra not only re-enacts the experience of previous tirthankaras but the Shatrunjaya Hill itself is venerated, as the mountain is considered shashvat (eternal and indestructible).

The Navanu Yatra can be undertaken any time of the year, except the four rainy months, called chaturmas, as it is a time of rest and discourse, when all movement is restricted to avoid killing microscopic lifeforms residing in waterbodies. The direct route starts from Jay Taleti (foothill) and covers a distance of 3.5 km uphill. Yatris climb 3,750 stairs to reach the top, then descend, and repeat the process two to three times each day, in order to finish the task within 45 days. If done with intervals, the yatra may take two to three months to complete. Apart from the 99 yatras prescribed by Jainism, yatris usually perform nine more journeys to the top, making it a total of 108 yatras; however, there is no restriction on the number of yatras that can be undertaken and many continue well beyond that figure. In addition, yatris are expected to trek six alternative routes, which cover other remote parts of the Shatrunjaya mountain range and take longer to complete.

I first visited Shatrunjaya with my family when I was 14. I remember seeing sadhus undertake this yatra, wearing white robes and walking barefoot. I was fascinated by the energy of the yatras and returned to shoot the yatra after 14 years, in 2018–19. This time, I stayed with yatris at Rajendra Bhawan, one of the many dharamshalas in Palitana. As a solo yatri, I was an exception, as in usual cases yatris visit in large groups, organised and sponsored by a sanghapati (wealthy patron of the community), whose duty is to bear the expenses of all participants.

Literally, shatrunjaya means ‘which conquers enemies’, an allusion to the conquest of the ego. This is why yatris must abandon the comfort of urban life and live the mendicant life of ascetics, before and during the yatra. They must abandon all material comforts and sleep on the floor, and avoid entertainment and all mechanised means of transportation. The food intake of the yatris is limited to once a day, usually in the evening, after they return from Shatrunjaya Hill. The food served is a basic Jain meal (a strictly vegetarian meal which excludes root vegetables like potato, onion and garlic), specially prepared for the yatris. All yatris must live a chaste life and abstain from sexual thoughts or mixing with persons from the opposite gender. All yatris are supervised by at least one acharya and his disciples, who belong to the ascetic branch affiliated with the respective local community. The acharya conducts pratikramana (introspection) ritual twice a day, once early morning and in the evening after yatris return from the yatra.

Traditionally, yatris commence first of the 108 yatras on the poornima (full moon day) of the month of Kartik (October–November of the Gregorian calendar). Yatris leave hours before sunrise as an early morning start makes the climb easier. I used to wake up at 4:30 am to start the daily yatra. Photography is not allowed and I had to hide my camera under my shawl. Being a Jain myself, it was easy to understand the rituals and interact with other yatris. Eventually, I familiarised with the yatris and they allowed me to take their photographs.

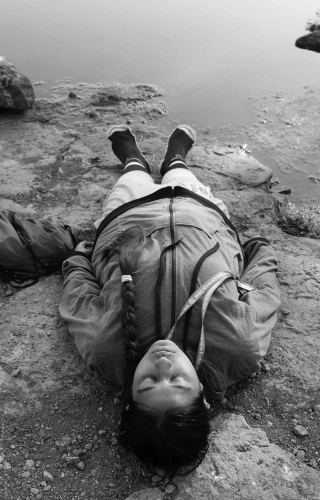

Performing the yatra is exhausting, particularly after sunrise, when the ground gets very hot. Walking barefoot can cut the skin and lead to blisters on the feet, adding to the suffering. The arid vegetation offers little shade and all yatris must observe strict rules when it comes to drinking water. They must abstain from drinking water until they have completed at least one yatra and can drink only boiled water, which is provided from water kiosks at regular intervals. If they perform more yatras on the same day, they may only drink water two more times before returning to their hostel. The yatra gets even more strenuous as yatris are also supposed to abstain from all food and drink for at least two consecutive days, called chhath. Chhath is a complete fast, and must be undertaken without halting their daily yatras. To overcome dehydration, yatris put a wet cloth on their head, wipe themselves with wet towels, and splash water on their faces. Some of the exhausted yatris hire locals who help them by pulling or pushing them along the way. During this difficult period, the reciprocal support between the yatris and their constant verbal encouragement to one another form an enduring experience of the yatra. On the route to Adishvara temple, yatris halt to perform obligatory rituals at five sacred sites. During the yatra, many yatris experience a ‘vision’ of Dada Adishvara and credit him for the successful completion of the task.

Because Navanu yatris arrive in batches and their stay is sponsored by a patron, they also leave together, at a designated time, which is about 45 days to two months after the arrival. The last yatra is marked by special observances: yatris collectively perform giri-puja,cleaning and worshiping every single of the 3,750 steps of the main route to the Adishvara temple. This is done as prayaschit (penance) in order to ask for forgiveness for any ashatna (ritual fault) which a yatri might have committed by accidentally trespassing the rules and regulations while performing the yatras.

For yatris, who successfully complete the yatra, the suffering is a positive and transformative experience. It is said that if one dies on Mt Shatrunjaya, they will surely attain moksha and get out of the cycle of life and death. Moksha though is a philosophical concept with inherent subjective interpretations. Through my work, I intend to find answers to questions related to personal interpretations of moksha and the various paths leading to it.