The four Swetambara Jain temples in Manicktala, Kolkata, are prime examples of the hybrid visual language that became popular in colonised India. Built over the second half of the nineteenth century, these temples show an overwhelming influence of European art and architectural styles combined with multiple regional artistic sensibilities.

Historically, every colonising culture has appropriated aspects from the culture of the colonised to incorporate it within their own cultural vocabulary. In turn, the colonised culture also assimilated the coloniser’s sociocultural aspects within their own language. European colonial expansion, especially the British colonial rule in India, effectively resulted in the rapid decline of the Mughal era. The British saw themselves as the true inheritors of the Mughal Empire. To attest Britain’s standing as the ruling power, public buildings that adopted an entirely new hybrid vocabulary were instituted. Mughal architectural elements were integrated within the European architectural vocabulary of the colonisers, and a new architecture style was developed; it was called the Indo-Saracenic[1] revival style, a combination of Islamic and neo-gothic/neoclassical styles. According to Mughal ruler Akbar’s historian Qandahari, ‘A good name for kings is [achieved by means] of lofty buildings…that is to say, the standard of the measure of men is assessed by the worth of [their] building and from their high-mindedness is estimated the state of their house.’[2] Architecture, for both the Mughals and the British thus, was the medium to represent a concept: the concept of power in the idea of the ruler.

In the colonial context of Bengal, the rich and the elite who could afford to build palatial houses for themselves mostly made their fortunes by serving the empire in one way or another. Understandably, their aesthetic sense was shaped by the class they served. Imitating their rulers’ taste, moreover, made them, if not at par, but closer to them in social and political hierarchy. The result of this was the incorporation or imitation of architectural motifs and styles, or even an entire architectural structure. In Bengal examples of this include the neoclassical building of the Marble Palace with statues and fountains in the garden built in 1835 by Raja Rajendra Mullick and the royal palace of Cooch Behar (1887) that was modelled after the Buckingham Palace in London.

We should keep in mind that from the eighth to twelfth century, the Rarh (southwestern part of Bengal) region had a thriving tradition of Jainism. In fact, historian Niharranjan Ray argues that the Jain sutra texts even from the first century AD mentions Banga (Bengal).[3] He also points out that an inscription from Mathura tentatively dated second century BC mentions a Jain bhikshu from the Rarh region who built and dedicated a Jain idol in Mathura.[4] Most of the surviving Jain temples in Rarh were built around the eleventh–twelfth centuries and followed the Oriya Rekh Deul style (a structure built more or less following a rekh [straight line] and the sanctum topped by a curvilinear shikhara with amalaka and kalasha). The Manicktala Jain temple cluster did not follow the traditional architecture of the Jain temples found in Bengal. As the families that founded the Manicktala temples migrated from the northern part of India to Calcutta, the Bengali Jain temples were not in their collective memories. These temples rather fell back on the designs of their northern and western counterparts. The influence of regional architecture styles of Bengal is limited within the use of a hut-like structure on top of the main entrances of the Parsvanath and the Chandapabhaji temples.

Reinterpreting the Architectural Elements of Jain Temples

The building process of the Manicktala Jain temple cluster started in the 1860s. Following a traditional northern Indian style in a broader context, a shikhara in the shekhari style (with smaller subsidiary shikharas called urushringas attached to the main one) tops the gambhara or garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum or the sacred innermost chamber) in these temples. The temples have square plans and are designed in the chaturmukhastyle (temple room housing the main shrine opened towards the four cardinal directions) with verandas running around the main chambers. The main shrine inside is surrounded by a pradakshina patha (circumambulatory path); because pradakshina or circumambulation of the deity is an important part of the worship ritual of the Jains, this path around the shrine is an integral part of the temple architecture. The eyes of the deities, figures of the ancestors, and Badridas Mookim, the founder of the temple cluster, are accentuated contrasting the uniformity of the rest of the body. This is a typical trait of Jain sculpture as seen in the temples at Dilwara and Ranakpur. The four temples situated in a group follow the Jain architectural concept of ‘temple cities’ as opposed to the isolated Hindu temples.

A curious example of the reinterpretation of an important Jain architectural motif can be seen in the Parsvanath temple. The inside of the dome that tops the space in front of the gambhara is densely decorated and has multiple figures attached to it. (Fig 1)These figures are believed to be representing 36 ragas and raginis. However, as there are only 32 figures, there is a possibility that instead of the ragas and raginis these figures represent celestial musicians and dancers who rejoice the presence of the jinas in the heavens. Such figures can be found in the murals in the Jain caves of Ellora or used as brackets in various Jain temples. It is also possible that the female figures are reminiscent of the figures of vidyadevis (goddesses of knowledge); though they do not embody the iconographic elements of the vidyadevis, the fact that they are 16 in number supports the possibility. They are a recurring motif in traditional Jain temples; for example, groups of 16 vidyadevis can be found in the ceilings of the dome in the main hall of the Adinath or Vimala Vasahi temple, the ceiling of Neminath or Luna Vasahi temple, both in Mount Abu and the ceiling of the dome in the Ranakpur temple.

One thing that marks this cluster, especially the Parsvanath temple, is the sheer opulence of materials; all the four temples use marble, imported Belgian glass, colourful tiles, European style statues, chandeliers, lush gardens, etc. This opulence is a general characteristic of Jain temples as seen in the Indian subcontinent; the temples also exhibited external signs of wealth which lent visibility and agency to the Jain community in the public sphere of colonial Calcutta.

Hybridity of the Temple Architecture

The Kolkata Jain temple cluster picked up salient features of typical Jain architectural traditions and reinterpreted them within the context of a different time and sociocultural space. Very prominently woven within this reinterpretation are the European motifs that largely contribute to the question of hybridity of the temples.The best examples of this hybridity could be found in the Parsvanath temple. The main temple building mostly follows a typical Jain temple structure; yet, within this structure, the columns that surround the veranda of the Parsvanath temple are Corinthian[5] in style. The fluted shafts are thick and as they are without any base, they stem right out of the floor. The absence of base perhaps reduces visual clutter: a base would have shortened the height of the columns and the veranda would look crowded. The top row of leaves on the capital is interspersed with male figures that appear to wear dhoti, kurta, and a headgear. The half columns on the exterior of the shrine walls also have a simpler version of the Corinthian capital. (Fig. 2)

The Parsvanath temple compound houses a large hall that was once used for religious gatherings and, occasionally, as a guesthouse. Inside this congregation hall, the doors are painted with a series of Ragamala (garland of ragas) paintings by the artist Ganesh Muskare.[6] Traditionally, the Ragamala paintings is a set of miniature paintings depicting Indian ragas. The ragas in the paintings are shown through colour, a verse about a hero and a heroine, and mood such as the pain of separation from one’s lover.[7] The paintings also illustrate the time of the day and the season in which the raga is sung; often, the paintings depict the deities associated with the raga. The uniqueness of the Muskare Ragamala series is its rendition in the Western landscape painting style. The artist has translated the general structure of the Ragamala painting in his own way; his method is to paint a generic landscape and include a motif that may be related to its counterpart in miniature. (Fig. 3) For example, Raga Deepak in miniature paintings is often represented as a nayaka (hero, male figure)riding an elephant holding a burning lamp;[8] in the Muskare version, this motif is simply translated into an elephant with a rider walking down a road amongst trees and shrubbery with a waterbody in the background.

Muskare’s use of the landscape genre to carry out his version of the Ragamala is another sign of the influence of European art or, to be precise, the British academic art. Landscape painting as an independent genre itself was a product of Europe. Before the introduction of landscape paintings by the travelling European artists such as Zohan Zoffany, Thomas, and William Daniell and so on who came to India in search of fortune and the exotic, landscapes in Indian painting were mostly mere backdrops of the main narrative or protagonist.

The fact that Muskare felt the need to translate a quintessentially Indian theme into a genre which is essentially European is also another aspect of the hybrid modernity of the colonised India. Headed by the British, the contemporary art scenario of India emphasised the superiority of British academic art style that in a way claimed to represent the whole of European art against the almost intuitive practices of Indian artists.[9]Mid-nineteenth century onwards, this tendency became even more prominent when fine arts colleges were established throughout India. There were amateur native artists trained privately or small studios run by British art practitioners or a native artist trained by such artists even before the art colleges. A demarcation line was drawn between the concept of an artist and an artisan and their respective practices based on, among other things, the knowledge of and training in European styles and mediums and the lack thereof. The students at such colleges or studios and their Indian patrons were exposed to the wealth of European art and trained to accept its superiority. The ways of looking at quintessentially indigenous themes shifted and the European artworks—often copies of the original—the art students saw provided a template for the way the indigenous artists visualised these themes; hence, when the Calcutta Art Studio[10] produced a chromolithograph print of Nala-Damayanti, a romantic couple from Indian mythology, the figure of Damayanti was based on a sleeping Venus—which may have been the Sleeping Venus by the Italian painter of High Renaissance Giorgione—and the figure of Yama in the Savitri and Satyavan print was based on Michelangelo’s David. Following this practice, when Muskare created his Ragamala series, instead of looking at the already existing plethora of miniature paintings of the same subject, he fell back on a European model, namely the landscape genre.

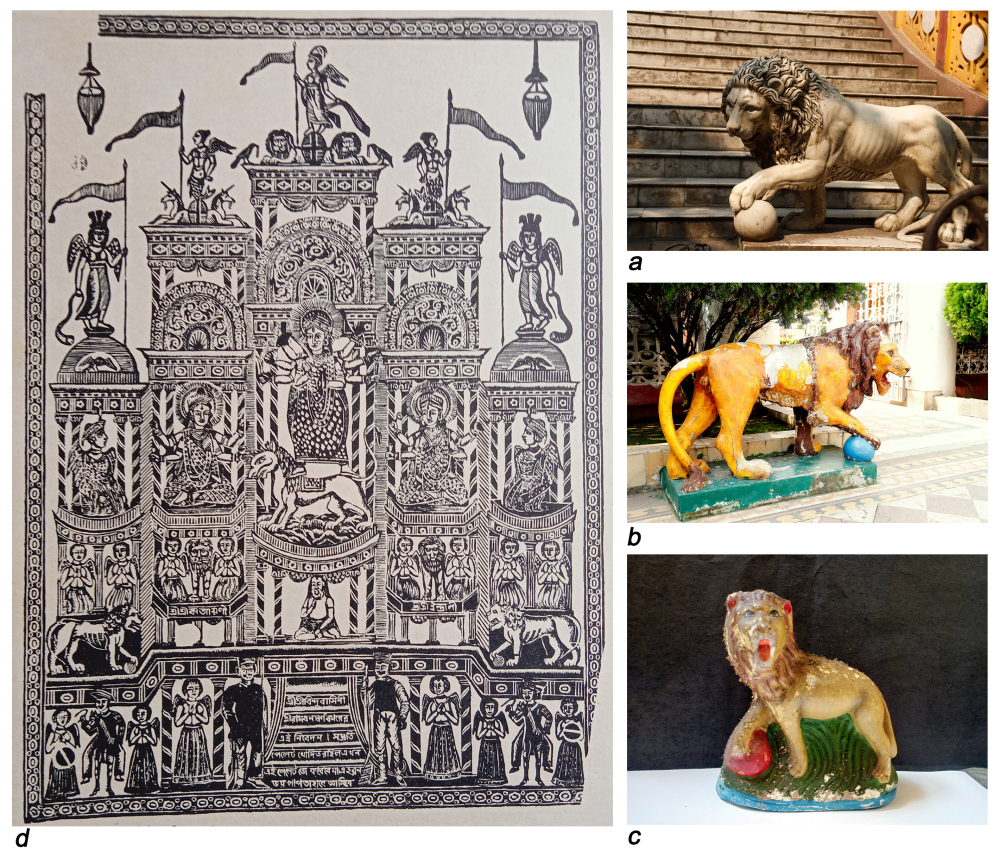

Interestingly, there are many statues of lion with a ball under one of its front paws. Except the dadawadi, all the three temples have more than one sculpture of this lion. Even though the lion is a symbol of Mahavira, this lion does not represent him, rather they are replicas of what is called the Medici lions. This is not to say that the lions found in the temple compounds are direct replicas of the Medici lions; originally Roman, the lion sculptures were acquired by the Medici family in the sixteenth century and eventually became popular as signs of aristocracy and strength. They were copied multiple times all over Europe including in Britain. As residents of the capital of a British colony, the elites of Calcutta could easily be familiar with the lions and use it as part of their visual language. In fact, Marble Palace also has the same lions used as garden decorations and similar lion motifs could be found in multiple woodcut prints; so, by the time the Jain temples of Manicktala were made, the lions were already a part of the visual material culture of colonial Calcutta (Fig. 4)[11].

An interesting element of the garden decorations of the Parsvanath temple is the coloured tiles. It is said that the tiles were imported directly from Persia, which could be the case since many elements of this temple were indeed imported and Persia had a long tradition of making and using painted tiles as part of architecture. (Fig. 5) Such tiles were already common in India through Islamic and Mughal arts that, in turn, were heavily inspired by Persian art, but the motifs such as portraits of European women or Greek and Roman type figures show some distinct European influence thus, there is a high possibility that they were made locally. Within these tiles, the floral motifs and abstract geometric shapes from Islamic architectures exist simultaneously with figures wearing hooded cloaks, breeches, and stockings that look quintessentially European, including princes, old men, and kings in elaborate oriental dresses and headgears, and women playing musical instruments wearing long dresses with dupattas around their heads. While some of the scenes appear to be illustrations of popular English stories, other examples may represent scenes from Oriental tales/sequences. By the time the Parsvanath temple were built, Arabian Nights, a collection of folk tales from the Middle East was already published (the first English edition was published in the early eighteenth century; curiously, the core of the original stories had some Persian and Indian connection). This book and various oriental harem scenes painted by European artists such as Eugene Delacroix, active during the nineteenth century, triggered an interest among the European audience for whom the Orient was synonymous to a mysterious land of exotic people and sensual women. The tiles are remarkable as they are where the Orient visibly meets the Occident on multiple levels.

Apart from these examples, many stray references to Western influence can be found around the Parsvanath temple compound. For example, the decoration of the entrance incorporates various visual elements of the Western type, namely, the curious painting on the ceiling of the entrance (Fig. 6) and the two tiles used among the decoration of the entrance exhibiting various motifs and designs (Fig. 7).

This amalgamation of multiple elements from different cultures that created a hybrid visual language was indeed the essence of the time; yet, somewhere it also mirrors one of the central practices of the Jain religion: principles of equality. Jainism does not believe in segregation based on caste and religion. The four temples welcome visitors from all backgrounds and walks of life. The confluence of different cultures within the spaces of the four temples truly reflected the concept of diversity in colonial Calcutta. Very recently, a group of Buddhist visitors from Japan contributed a sculpture to the decoration of the Parsvanath temple compound, adding to the same tradition.

Notes

[1] Saracenic means Muslim in Medieval Latin.

[2] Koch, Introduction to Mughal Architecture.

[3] Ray, ‘Dharmakarma: Dhyandharona.’

[4] ibid.

[5] One of the three principal orders or categories of columns of Ancient Greece and Roman architecture also adopted this style. Earliest and simplest of the three Greek orders, Doric columns are characterised by plain and circular capitals. Last developed among the three principal Greek orders, Corinthian columns were the most ornate ones. They are characterised by elaborate bell-shaped capitals with double rows of acanthus leaves and scroll motifs. The shafts are slender and often fluted.

[6] There is no information available on the artist. All that can be said about him so far is that he was trained in Western style of painting and was active during the second half of the eighteenth century. His only recognisable work is the Ragamala series. He is now so obscure that no textual or digital source mentions him. Raibahadur Badridas Mookim imported many elements from outside Bengal and India. He also brought many of the builders from Rajasthan; it is possible that he had invited Muskare from outside Bengal as well.

[7] For example, the Raga Madhuvanti is considered to be a romantic raga. In the Ragamala paintings it is usually depicted through a woman (often Radha) separated and pining for her lover (often Krishna).

[8] Deva, ‘Raga–The Melodic Seed.’

[9] Som, ‘Upadesher Shilpabidyalay Suchana o Bikash,’ 128.

[10] Established in 1878 by Annada Prasad Bagchi, the Calcutta Art studio produced and sold prints of Hindu mythological subjects. Bagchi belonged to the first batch of students at the Calcutta School of Art, established in 1854 (now the Government College of Art and Craft). The studio is still in business, operating from its original address.

[11] There is an almost similar lion called the Albani lion, now in Louvre, from the collection of Alessandro Albani. Both the Medici and Albani lions could be the inspiration of the Lions at the Jain temple cluster as both were Roman sculptures of Hellenistic origin. But it is probably safe to assume that the lion with a ball composition found in Calcutta, replicated in varied qualities and mediums were indirectly related more to the Medici lions because of its visibility in the public sphere of Calcutta through replicas than their Albani counterpart. The Chinese Foo Lion sculptures also have an almost similar composition. Even though the lion symbolism was introduced to China from India through Buddhism and there was already a large Chinese population settled in India by the late eighteenth century, it is unlikely that the symbol came back to India with a different meaning, in a different form and became a part of the popular visual imagination of the nineteenth century Calcutta. Also, if an immigrant culture has an element that is similar to an element belonging to the more powerful and dominant culture of the rulers then it is a matter of debate which would be adopted readily by the indigenous people.

Bibliography

Deva, Bigamudre Chaitanya. ‘Raga—The Melodic Seed.’ In Indian Music, 6–21. New Delhi: Indian Council for Cultural Relations, 1974.

Ray, Niharranjan. ‘Dharmakarma: Dhyandharona.’ In Bangalir Itihas, Adi Parva, 493–494. Kolkata: Dey’s Publishing, 1949. Accessed March 25, 2020. https://archive.org/details/BangalirItihasAdiparbaByNiharranjanRoy

Koch, Ebba. Introduction to Mughal Architecture, 10–13. New Delhi: Archeological Survey of India, 1990. Accessed January 17, 2020. https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.79132/page/n5/mode/2up

Som, Sovon. ‘Upamahadeshe Shilpabidyalay/ Suchana o Bikash.’ In Shilpa Shiksha o Aupaniveshik Bharat, 64–298. New Delhi: Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 1998.