This is the fourth of the six lectures delivered by prof. Velcheru Narayana Rao as part of the Nauras lecture series held at Bangalore International Centre, Bengaluru, May 2019.

Transcript

We have been translating for a long time. As someone who has translated almost fifteen books from Telugu literature to English, I must know how it does not work. We did a lot of work but we were always disappointed—this is not a good translation.

What is the conventional, the traditional understanding of translation? What is the traditional concept of translation? Indian literature takes the word into two parts, shabda and artha. Shabda is the sound part and artha is the meaning part. There are texts like the Vedas, which are totally shabda, you cannot translate it because you cannot translate the sound of Vedas, the swara of Vedas and, therefore, Vedas was never there in India until recently, which is nonsense. The next group of texts are the Puranas, they are artha pradhana texts, the meaning is important there, not the words in which the text is told, so that you can translate. Mahabharata, Ramayana, any of the Puranas, sure go ahead, you can translate them because the words in which the text is produced is not important, and the meaning is. You can always take the meaning and give your own words to it. There are pradhana texts where the sound is important and so is the meaning.

Poetry was never translated in India. Kalidasa, Bhavabhooti and all those great poets of Sanskrit were never translated into any other language. Why? Because they are combined, the words are inseparable from the sound of the word, and sound cannot be translated.

So what is it we translate after all? Kalidasa, Bhavabhooti—all these poets were never translated; either you read them in Sanskrit or you don’t read them. This is something many people don’t realise. In fact, so much translation was made from the Puranas, Shastras, all those texts. There is no word for translation in Indian languages. We borrowed the word anuvada, which means following somebody. So that is a loan translation from English.

But without translation, there is no literature in many Indian languages. Let us take the case of Telugu, which I know more than any other language. Nannaya, an eleventh-century poet who translated Mahabharata into Telugu, was called the first poet in Telugu. Nannaya’s patron is Rajaraja. Let’s listen to what Nannaya’s Rajaraja asked him to do (in Nannaya’s words):

jana-nuta-krshnadvaipa

yanamunivrshabhabhihita mahabharata-bad

dha-nirupitartham erpada

denuguna raciyimpum adhika dhisaktimeyin

Rajaraja was telling his poet:

Compose in Telugu

the proven meaning embedded

in the Mahabharata,

spoken by the great sage Krishnadvaipayana.

You have a powerful mind.

There is a meaning embedded in Mahabharata, take that meaning out and say it in Telugu. He is not asking the Mahabharat to be translated word to word, there is a meaning in it. Unpack that meaning, take that meaning and translate it into Telugu.

So you ask this question, was a poem ever translated? The answer is no. What am I doing when translating Telugu poetry into English? Honestly, I am violating tradition. I am not doing what tradition wants me to do. If I was to follow tradition, I should not be translating. Poetry cannot be translated, but I have violated the tradition. What do we do when we violate tradition? We develop a new protocol, translate the reader, and not translate the text—that is the important thing.

Telugu and English are worlds apart—syntactically, semantically, culturally. We have to do this translating in a language that is not anywhere close to Telugu. You probably know this. Telugu and all other Indian languages are subject-object-verb languages, English is a subject-verb-object language. There is a huge difference in syntax itself. So if you take an English poem you have to turn it upside down. Telugu allows for long compounds, longer, much longer than Sanskrit. What do you do when you encounter a compound like that? In this verse, all this in red is one compound

ata jani kance bhumi-suru d’ambara-cumbi-srassarajjhari

patala-muhur-muhur-luthadabhanga-taranga-mrdanga-nisvana

sphuta-natananurupa-parphulla-kalapa-kalapi-jalamun,

kataka-carat-karenu-kara-kampita salamu sita-sailamun

This verse is Peddanna describing the Brahman who saw the snow mountain for the first time. (recites)

How do you translate it into English? The entire red line is one whole compound—we break it up, the meaning and not try to translate the song, we cannot translate texture, don’t attempt that. This how we translate it:

The Brahman went and saw Snow Mountain, its tall peaks

kissing the expanse of sky, with many rivers rushing

downward, rumbling like the beating of a drum,

on and on, while peacocks danced in time,

spreading their splendid tails,

and elephants roaming the slopes

Shook the sal trees with their trunks.

What a deep text it is, compared to the Telugu version, but that’s all we can do. More importantly, in Telugu, let us go back to the poem, the object, what he saw, the snow mountain, is at the end of the line.

ata jani kance bhumi-suru d’ambara-cumbi-srassarajjhari

patala-muhur-muhur-luthadabhanga-taranga-mrdanga-nisvana

sphuta-natananurupa-parphulla-kalapa-kalapi-jalamun,

kataka-carat-karenu-kara-kampita salamu sita-sailamun

In our translation, it comes at the very beginning of the line. Look at the last word—sita-sailamun is the object, kanche is the verb, bhumisurudu, the noun. Sita-sailamun, the object, comes at the very end of the line, whereas in the translation, the snow mountain is in the very first line. To turn the poem upside down, we have to begin at the end. That is what you should do when you are translating subject-object-verb language to subject-verb-object language.

Suppose you say Rama killed Ravana, that is English. Rama is the subject, kill is the verb, and Ravana is the object end. There is a joke, if I said kill, why would Ravana stay there, he would run away, but that’s English. In Telugu it is Rama-Ravana-killed.

So this kind of a simple syntactical variation makes you want to play games in the translation of an Indian poem—bringing the end to the beginning.

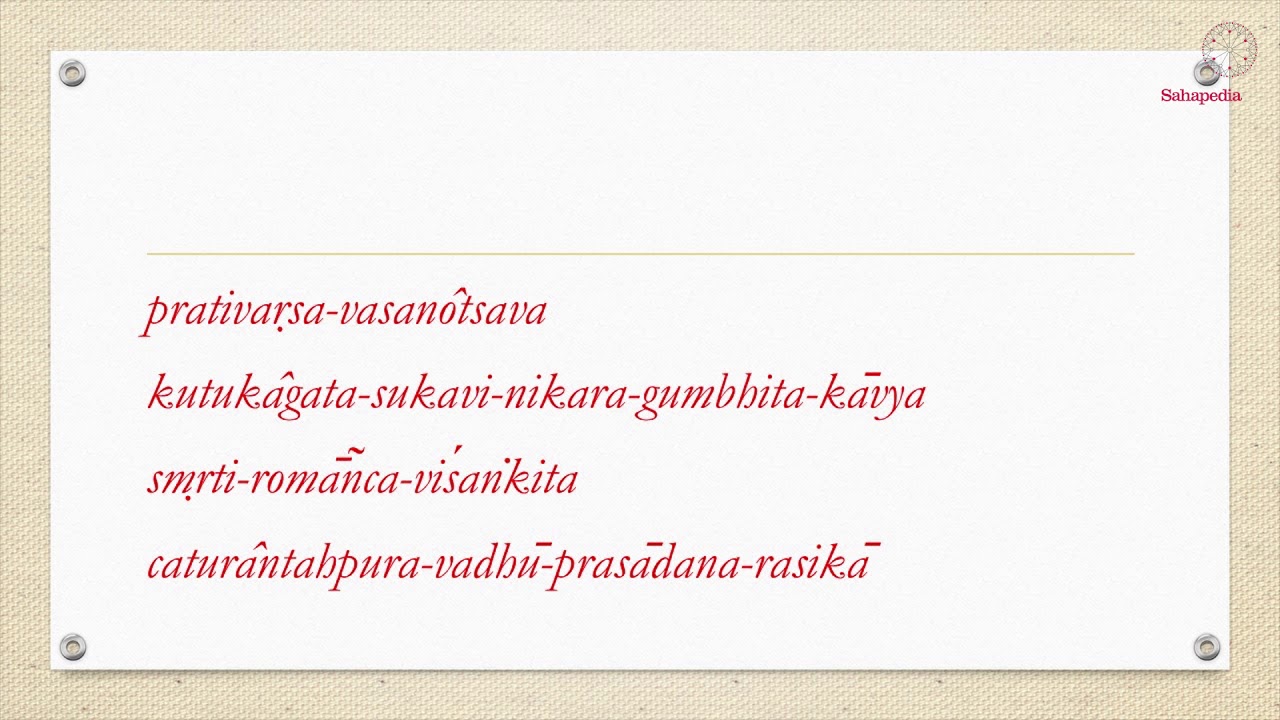

This is Krishnaraya who is being talked about by his poet, who is describing him. This long compound in red is a whole story. (recites)

prativarṣa-vasanôtsava

kutukâgata-sukavi-nikara-gumbhita-kāvya

smṛti-romāñca-viśaṅkita

caturântahpura-vadhū-prasādana-rasikā

It is an evocative and the evocative tells the whole story. When you translate, you unpack the compound. You begin with

Your hair stands on end with excitement

when you think of the poems sung by good poets

who come every year for your spring festival.

You’re skilled at comforting your wives

when they suspect that you’re aroused

by thinking of another woman.

The king is thinking of poems, the poems give him loose thoughts, and his hairs stand on end. His wives think he is thinking of another woman, and the king has to have the skill of comforting them, saying: No that is not the point, I was thinking of the poems that the poets have sung today at the vasantotsava, and remembering that my hairs stood on end. This whole story is contained in one long compound. Now to break up the compound. (recites it again)

Every year, prati varsha poets come out of curiosity and they produce poems and smriti romacha, you get pleasure thinking of the poems you wrote in the day, and caturântahpura-vadhū-prasādana-rasikā, he explains to them it was the poems that made his hairs stand on end.

It is a fascinating verse telling a story in one compound. We have to unpack the compound to translate the story. Is it a good translation? I don’t think so.

Now the question: What does a good translator do for a poem? A great poem is more than one poem. A poem is more than one. In that poem in your language there is another poem embedded in it. A good translator sees in the original poem a hidden one that the native readers may not be aware of. Native readers miss out the poem in it and the translator has to pull it out. The native readers who then read the poem say: We didn’t know that there is another poem in our poem!

Translation is also an interpretation; no translation is literal. Tell the native speakers this is the poem you haven’t seen; now when they read the original in Telugu they can say: Yeah, it was in it, we don’t know how we missed it. That’s what a good translation does—that is the purpose of a good translation. Every time a good translation is produced there is an opportunity to interpret the translation and show that it has in it a different poem that the native speakers were not reading and we are bringing it out.

Once a translation is made of this poem into another language of another culture, bridging code, space and time, the original itself is transformed for the native readers, who discover, to their surprise, a new poem in their original, while at the same time the world of the culture into which the translation is made is reorganised by the entry of the translated poem into its literary system.

I gave you a long compound which cannot be easily translated and how you have to unpack it to find their solution. There is something more interesting and something mindboggling in Telugu and Sanskrit poetry. This is called chitra kaavya.

A poem written like a cow urinates, goumutra kaavya. You write the poem in that order. How do you translate this? You don’t. You have to write an essay. This poem is supposed to make you look at the same syllable again and again as you go back and forth.

I will show you a more complex one.

This is kundali naga bandha, it is like a serpent and letters are put in it. Why? There is a reason. Narada was praising Krishna in this form. You can see that you go over one letter over and over again—repeating the syllable when you read this poem is exactly what makes you think of Krishna again and again. This was the idea. The point is you can read it in a number of ways; the point is each letter acquires an independence of its own. When you repeat a letter over and over, you think of Krishna. This is a bandha. If that is the translation, what do we do? We write an essay about the nagabandha and gomutrikabandha—about why the poem is here in this form. The poem is not there for the meaning of the poem, its meaning is very simple. The poem is there for repeating the syllable again and again as we go through it.

It is an enormously interesting text. In fact, there is a lot of discussion on this and nobody was able to interpret why these bandha poems were composed. And we were trying to do in the translation the Harshita Kamath and I translated this text Parijata Apaharanamu -‘Stealing of the Parijata Tree’. At the end of the text, when Narada was leaving, he gives this praise (nagabandha) to Krishna and goes away. So what is going on there? A long essay produces the meaning of the poems. That’s where, I say, you have to bring the reader—translate the reader. Tell the reader in our culture: Look at it this way, work it out this way, in a way that you cannot imagine happening in English. Unless you understand how the text works, you cannot translate it. That’s what I mean by preparing the reader to read something that is entirely different, to help his understanding of poetry.

Now what is the meaning of all this. In Parijata Apaharanamu, the whole idea is to make him be superior. The Parijata tree was stolen from Indra’s garden and planted in Satyabhama’s backyard. Satyabhama was upset because the flower was given by Narada to Krishna, who was sitting in Rukmini’s house. He brought this flower and gave it to Krishna saying: Hey, Krishna! This is a great flower. No human can ever get it. This flower never wilts, fades or loses its fragrance. There is something more interesting for Rukmini. When you are making love to her, if you are tired, this flower restores your strength, and you can make love to her without losing strength.

It is a very open and clear story that Narada is telling. Why was he doing that? His business is to create quarrels. He knew that Satyabhama was very proud of her beauty and very proud of the importance Krishna was giving to her among all her co-wives. Narada says: That Satyabhama thinks she is the greatest of all your wives. No, she is not. You, Rukmini, with this flower, will become the greatest woman of all Krishna’s wives.

There are maids and other wives who come to spy on what is happening, and they go back to report to Satyabhama: Your husband, who pretended to love you more than anyone else, actually loves Rukmini more. He gave the flower to her and not to you.

Satyabhama is very upset. There is a room in the palace for a woman who is angry, kopaghara, a room where women who are angry can go and lie down. Krishna goes there and says: Oh my God! She is in the kopaghara. I need to go and appease her. He tries to tell her that he really loves her. Satyabhama wouldn’t listen. He tries to fall at her feet, and she kicks him with her left foot.

Krishna says: Oh! I hope your foot doesn’t hurt by hitting me. He says: Listen, you are upset about the flower. I will bring you the entire tree, not just one flower, and plant it in your backyard. How about that?

And Satyabhama says: Alright then. That’s exactly how the story goes. The interesting thing about the story is that Indra doesn’t know Krishna is God. Krishna is stealing a plant and taking it away with him, and so Indra fights a battle with him. Indra calls all his assistants, the lords from all the directions, and they fight on behalf of Indra. They fight and fight, and they cannot defeat Krishna. Indra finally uses his Vajra, and that weapon, even that, cannot defeat Krishna. Then Indra falls at Krishna’s feet, saying: Krishna, you are God, I am sorry I am fighting with you. So finally, the interesting thing is how the tree is then taken. Garuda, the bird, carries it to the city where Satyabhama lives. Beautiful descriptions are given there—how the fragrance of the tree and its flowers makes old people young suddenly—everyone became young. Krishna plants the tree in the backyard of Satyabhama, and then a whole lot happens.

The idea is, ultimately, why was Narada praising Krishna as God in all these cryptic verses? Krishna knows that he is a human being, and other people should treat him as a human. In a way, Paraijatapaharanamu is the celebration of a human being—human love is superior to any love.

I do not know if I can go into theory. Rasa can be enjoyed only by humans; gods do not enjoy rasa. If you do not have any pain, you don’t have any pleasure either. Gods who do not feel pain don’t understand love without pain exists. That is what is written in the text. The text ultimately tells you that being human is superior to being gods. Does anybody who reads the story think that way? No.

That’s the idea. The translator has to show that is the meaning of the poem. It is not implicit. That’s how translations tell the original readers what the book is about, how they should understand it. Translation not only reproduces in a different language what a book is, but tells you that there is something the book has which you have missed and this is it. That is the idea of translating all these books. Each of these books have a long afterword, not just a preface. The afterword tells how you should read the book, what exactly is the meaning of the book. Then you should go back to the translation and read it.

So our effort is to make the book accessible to people of a new culture, including us, for that matter, who have missed the original meaning of the text. The idea of a translation is to make your own text accessible to you. Translating the reader has a double purpose. Translate the foreign reader and the Indian reader also because you have not read the book as it was before. In effect, translation is an interesting job. When we translate old books written so far, we discover: Hey, we didn’t know that there is this meaning in the book, and we should write about it. You know something, Telugu readers do not know that meaning either! If they take the time to read the translation and the afterword, they would know it. However, unfortunately, not many people read it. They go: Oh! We know the book in Telugu; we don’t have to read a translation.

There is something else going on in translation—what I call the politics of translation. In Telugu, at one point in time, it was necessary to have a Sanskrit original for the respectability of the work. If there was no Sanskrit original, they invented one and said that their work is a translation of that original, because, then, translations were more respected if they had a Sanskrit original.

There is a book called Kridabhiramamu, it is worth a separate lecture. Kridabhiramamu is still discussed among Telugu literary critics, whether Srinatha wrote it or Rallabharaya. That is not the issue, the issue is different. Kridabhiramamu is a parody, a parody of the whole culture. It parodies the practice, the convention of finding a Sanskrit original for every work you do. It parodies even the habit of inventing a translation, and says that it is a translation of a Sanskrit text. It invented “Premaabhiramamu” in Sanskrit and said Kridabhiramamu is a translation of it. Even now, people are looking for Premaabhiramamu! But no, it doesn’t exist, that was a joke. Premaabhiramamu doesn’t exist. Who reads this text this way? The only questions readers have about Kridabhiramamu is whether Srinatha wrote it or Rallabharaya. Because a lot of verses by Srinatha are borrowed in the book. They are not actually borrowed, they are like Srinatha, and they are parodies of Srinatha’s work. A parody does not produce the original but looks like the original. If you don’t realise it is a parody, you think it is an original. That is what Kridabhiramamu is.

English is a world language. Good or bad, if [a text] has to go to the world, it has to go through the door of English and that is why we translate into English. In translating, we are translating the English readers to think like us. That is what a good translation should do; that is what we thought we were doing in all our translations. I do not know if we succeeded. You should tell me! If you finish reading any book at all, send me an email. [Tell me] whether it is a good translation or a horrible one. I would like to hear that.