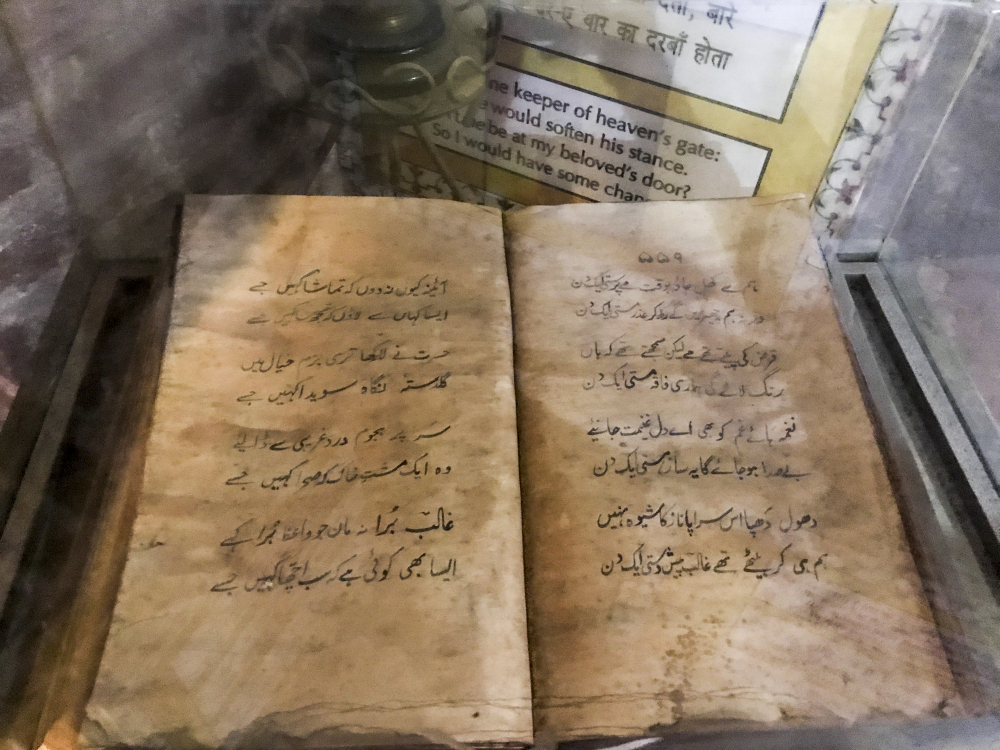

Living through the carnage of the 1857 Revolt, Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib’s was most pained at the ruin of his beloved city, Delhi. Interestingly, we find that while in his ‘official and published’ diary, ‘Dastanbuy’, he writes in support of the British (his then patrons), some personal letters indicate that he was as much angry at the British as he was with the rebels for destroying Dilli and its inhabitants. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

The heart is not stone or steel but will be moved. The eyes are not lifeless cracks in a wall but will shed tears at the panorama of death and at India’s desolation. The city of Delhi was emptied of its rulers and peopled instead with creatures of the Lord who acknowledged no lord—as if it were a garden without a gardener, and full of fruitless trees.[1]

This is the metaphor Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib invokes to describe the dire situation in Delhi during the Revolt of 1857. While many eyewitness accounts of the revolt have been published[2] in books of history and politics, Ghalib’s account is slightly different as it expresses anguish for the loss of the very soul of Delhi. Dilli was Ghalib’s home. It was emblematic of all that the famous poet stood for—the beauty of Urdu, the tehzeeb (culture) of day-to-day conduct, the bazaars of Chandni Chowk and the splendour of the Red Fort. With the revolt, he writes, any semblance to the city he loved was destroyed.

Also see | Prof. Ateequllah on Ghalib

Ghalib came to Shahjahanabad when the authority of the Mughals had begun to fade away. The city had been invaded multiple times and its inhabitants were living in a deplorable state. Many of his contemporaries—such as Mir Taqi Mir and Shaikh Muhammad Ibrahim Zauq—wrote poetry in the shehr-e-ashob genre (a classical poetry genre reworked in eighteenth-century India to express lament for the city) to mourn the loss of the city’s grandeur. However, Ghalib also had to bear the burden of living through the carnage of 1857. He writes about his misfortune:

For you this is only a sorrowful story, but the pain is so great that to hear it the stars will weep tears of blood.[3]

On the Record

Ghalib writes about experiences of the revolt in his diary, the Dastanbuy (Persian for bouquet), which he kept from May 1857 to July 1858.[4] In it, he describes the looting and killing that took place in 1857 during the hottest months in Delhi. On first read, the diary seems overtly sympathetic of the British and critical of the rebels. He says the latter were ‘destroying the honour and prestige of Delhi.’[5] However, we must remember that with Mughal power on the decline, patronage was hard to come by. It was the British who were now Ghalib’s benefactors. As Ghalib reminds us, right from his childhood, he had ‘eaten the bread and salt of the British’.[6] In such circumstances, scholars say,[7] Ghalib uses the Dastanbuy as a petition to request the British power ‘for title, for robe of honour, and for pension.’[8]

After the British victory, they suspected the Muslim population of Delhi of sympathising with the rebels. Many of them, including Ghalib, were rounded up for waging war against the British. The Dastanbuy, published in 1858, was thus a way for the poet to ‘seek the shelter of the Lord from these unwarranted arrests.’[9] As scholar Shikoh Mohsin Mirza writes, ‘In a letter sent to his pupil-friend Munshi Hargopal Tafta in August 1858, Ghalib writes—“I want to get it (Dastanbū) published immediately so that I can send a copy to Governor General Bahadur, and another through him to the Queen of England.”’[10]

Also read | Sufi Shrines of Shahjahanabad

In Dastanbuy, Ghalib goes to great lengths in condemning the rebels. Giving an account of May 11, 1857 (the day the revolt broke out), he writes, ‘rebellious soldiers from Meerut, faithless to the salt, entered Delhi thirsty for the blood of the British.’[11] These ‘wayward, hostile rebels’ looted the women’s ornaments, killed officers in their barracks and ‘ravished the city like madmen.’[12]

The British meanwhile took control of the Ridge and converted it into ‘a kind of fortress.’[13] By September 1857, they had occupied Kashmere Gate and Delhi was gone from the hands of the rebels. Not surprisingly, Ghalib paints this time as a moment of liberation. ‘After four months and four days the shining sun emerged and Delhi was divested of its madmen and was conquered by the brave and the wise.’[14] But the pakka Dilliwaala that he was, he could not stop himself from grieving the attack on his fellow residents, even if it was done by his patrons.

Their [the British] anger at the citizens of Delhi was so great that, after capturing the city, one would think they would leave not even a dog or a cat alive.[15]

Off the Record

However, interestingly, his numerous letters to his friends—in which he wrote more freely—indicate that the poet was as angered by the British as the rebels. In this letter, he writes of British cruelty towards the inhabitants of Delhi:

The city has sustained five attacks. The first was that of the army of the native sepoys, who robbed the confidence of the people of the city. The second was that of the army of the British who destroyed life, wealth, honour, property, indeed, all signs of our life.[16]

Sarcastically commenting on the British government’s decision to first ban Muslims whom they distrusted from Delhi, only to allow them in later for a fee, he writes:

Whether a Muslim can come back to the city depends on how much

of the fee he can pay. The government of course decides on how

much you will have to pay. They ruin you but they say you are

settled again.[17]

As Urdu scholar G.C. Narang writes, ‘if we wish to know Ghalib’s real attitude towards the Mutiny, Dastambu is not enough; we must also take his letters into account. At the most, we may take Dastambu as Ghalib’s “well-prepared defence.”’ The rast khezi bija, or ‘the unwarranted revolt’[18] (as he called the revolt) took much more than his city—it robbed him of his characteristic wit and humor. Even poetry, his dear companion, could no longer provide him solace. He writes, ‘how can poetry soothe me when my heart is burned with hot sighs?’[19] While his pension was restored in 1860, his desire to become a poet laureate was never realised.[20]

Even though in the Dastanbuy Ghalib sided with the British, he could not ignore the violence that both sides had unleashed on his beloved city. For Ghalib it was Delhi and its mohallas (localities) that suffered. The mushairas (poetry gathering) of the Qila-e-Moalla (Red Fort), the hustle-bustle of the streets of Chandni Chowk, the sellers and merchants who were the life of the city, were all gone. Ghalib wondered if Delhi was anything without them:

Delhi meant the Fort, the Chandni Chowk, the daily bazaar near Jama Mosque, the weekly trip to the Jamuna Bridge, the annual Fair of the Flower-sellers. These five things are no more. Where is Delhi now? Yes, there used to be a city of this name in the land of Ind[ia].[21]

This article was also published on The Citizen.

Notes

[1] Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, trans. Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1970), 33.

[2] V.N. Datta, ‘Ghalib’s Delhi’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 64 (2003): 1103; and Rana Safvi, ‘What happened to the Mughals after the fall of the Mughal Empire?: An intense curiosity led me to research on the life of the dynasty after the British took over Delhi on September 14, 1857’, Daily O. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.dailyo.in/arts/mughals-fall-old-delhi-bahadur-shah-zafar-revolt-of-1857-british-hazrat-nizamuddin-auliya/story/1/14095.html.

[3] Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, trans. Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1970), 34.

[4] Ibid., 69.

[5] Ibid., 40.

[6] Ibid., 30.

[7] Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi, ‘Introduction’. In Ghalib, Dastanbuy; G.C. Narang, ‘Ghalib and the Rebellion of 1857’, Indian Literature, Vol. 15, No. 1 (March 1972), 5–20; Pavan K. Verma, Ghalib: The Man, The Times (Gurgaon: Penguin Group, 2008).

[8] Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, trans. Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1970), 69.

[9] Ibid., 53.

[10] Shikoh Mohsin Mirza, ‘150 Years of Mirza Ghalib: How He Navigated Turbulent Times, Inspired Future Rebels’, The Wire (October 6, 2019). Accessed February 5, 2021. https://thewire.in/books/150-years-of-mirza-ghalib-how-he-navigated-turbulent-times-inspired-future-rebels.

[11] Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, trans. Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1970), 31.

[12] Ibid., 31–35.

[13] Ibid., 36.

[14] Ibid., 40.

[15] Ibid., 50.

[16] G.C. Narang, ‘Ghalib and the Rebellion of 1857’, Indian Literature 15, no. 1 (March 1972), 15.

[17] Ibid., 16.

[18] Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, trans. Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1970), 30.

[19] Ibid., 35.

[20] G.C. Narang, ‘Ghalib and the Rebellion of 1857’, Indian Literature, Vol. 15, No. 1 (March 1972).

[21] Pavan K. Verma, Ghalib: The Man, The Times (Gurgaon: Penguin Group, 2008), Chapter Four, Apple Books, 427.