Water is pure, Water is natural,

Water is healthy, Water can help all.

Water is simple, Water is free,

Water can help the lives…The lives of you and me!

Olivia Taylor

These lines by Olivia Taylor aptly define the importance of this odourless and colourless substance called water in our lives. It is an indispensable part of our existence and has a close connection with human settlements across the globe.

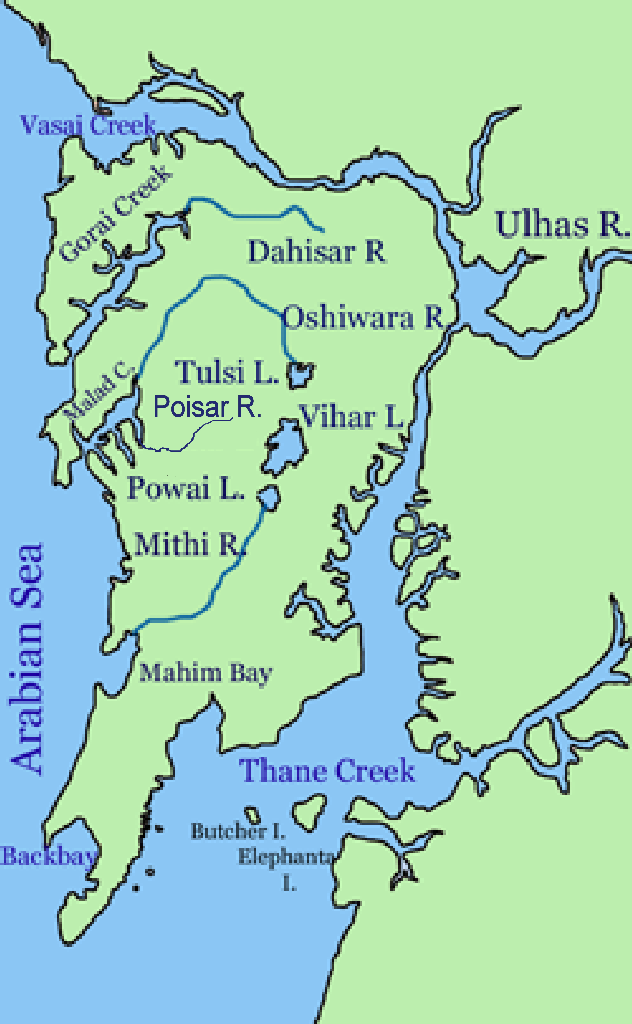

Figure 1. Water gushing out of Tansa Dam. Source: Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

Mumbai is the only city in the world which is surrounded by saline water bodies on three sides but there aren’t enough natural sources of potable water that can quench the thirst of the ever-growing population of this city. The history of Mumbai’s islets, before they were connected to form a big metropolis, is intriguing and plays a vital role in the history of the region. The advent of the British rule gave new dimensions to the city and the waves of settlements required a lot of urban planning, sanitation and building of habitation spaces for the people while maintaining a steady source of potable water, making the city what it is today.

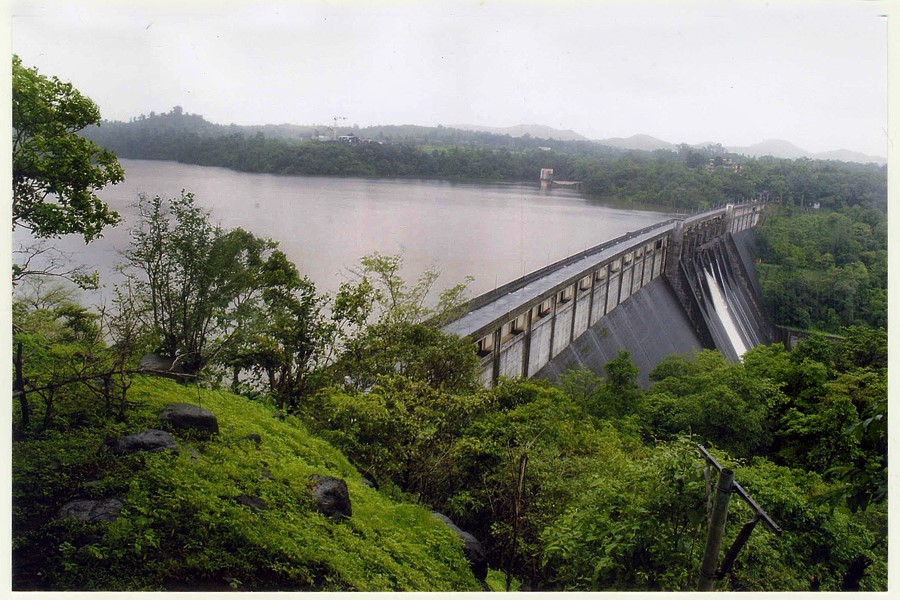

Figure 2: Map showing the Tulsi Lake, Powai Lake and rivers like Mithi, Dahisar, Oshiwara, Ulhas spread in the city. Source: Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

The demolition of the fort walls in the early nineteenth century, ushered in a gradual change in the city initiating its journey towards becoming a modern metropolis. As it grew in population and expanded geographically, the paucity of water was a major concern that the city faced. The process of how potable water first made its way to the city is an insightful tale of events that marked the nineteenth century.

The history of Mumbai’s water supply systems involves years of work by pioneers and noblemen. Before the large projects such as Vihar, Tulsi and Tansa were undertaken in Mumbai, pious citizens from the Parsi and Gujarati communities constructed many tanks and wells for public good. Owing to the scarcity of water, the tanks that existed in the pre-British period were insufficient and hence major water tank projects like C.P. Tank, named after the philanthropist Seth Cowasjee Patel, came up. Three wells by Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, Framji Cowasjee Banaji’s Powai Estate and Water Trust deed were bequeathed after the drought in the early 1800s. Foreseeing the intensified problem of water shortage in the subsequent years, another desirable solution was to dig ditches in open grounds and gather natural rainwater therein. But over a period of time, none of these early schemes of water provision and management could meet the needs of the citizens since there was a tremendous increase in water consumption.

On June 2, 1845 the citizens of Mumbai protested against then prevalent water supply systems which eventually led to the formation of a two-tier committee to study and chalk out solutions to this problem. The preliminary report submitted by this committee stated that there was a need to take immediate action to enhance the water supply to the city. In lieu of this, the land near Vihar village at the source of the Mithi river was chosen to construct a dam. Thus, the first major scheme of drawing water from a far-off place into the municipal limits of the city began with Vihar Water Works; approved by then Governor General Lord Canning. The work started in 1856 and was successfully completed in 1858.

A huge pipeline with a 32-cm circumference was laid down, breaching the gap between Vihar Lake and the main city. During the early years of its inception, it provided 32 lakh litres of water every year until 1872, when another pipeline was laid and the height of the dam was increased. This provided an additional 37 lakh litres of water to the city. But even this wasn’t enough to meet the needs of the city, which further led to the commencement of Tulsi Water Works project in 1879.

Figure 3. The Overflowing Tulsi Dam Water. Source: Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

The rock-cut cave site of Kanheri, situated now in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, is known for its ancient water systems. The reservoir dam here was connected to Tulsi Lake since ancient times and later this very Tulsi Lake continued to serve the city, now in the form of a modern supply system. These extensive water work projects proved very useful while also giving birth to the idea of Tansa Lake in 1892. The requirement of water supply was increasing with the growing city and these projects were taking root and progressing at a steady pace.

Figure 4. Water flowing from Tansa Dam. Source: Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

The Tansa Dam is 2,804m long and from here a 48 inch giant pipeline transported an additional 77 lakh litres of water to Mumbai. From 1914, this pipeline has been serving the city’s reservoirs before passing through mountainous regions. To further meet the increasing demands of the city, the corporation decided to build a dam on River Vaitarna and release the collected water in Tansa Lake. This work which commenced in 1948 was completed in 1957 under the supervision of the Corporation’s Engineer the Late N.V. Modak. Owing to his immense contribution to this project the Vaitarna Dam was renamed as Modak Sagar, which continues to play a vital role in the potable water supply of Mumbai even today.

Figure 5. Vaitarna alias Modak Sagar Dam. Source: Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

Modak played a pivotal role in formulating decisions of distributing water from all the dams into various reservoirs in the city located at places like Powai, Worli, etc. The water is chlorine-processed in eight reservoirs like these and is then finally made available to the people. In accordance with these developments and to adequately meet the ever-increasing water needs of the city, the Bhadra Dam project was the next important step taken up by the government. Another project on the Madhya Vaitarna Dam has also recently been taken ahead. In order to distribute such large quantities of water, the planners work with the law of gravity, thereby creating a successful water management system.

Thus, the water that people consume everyday goes through this long process before it becomes potable and fit. To meet their various needs—right from drinking, washing cars and household chores— these gallons of treated water is used by Mumbaites without knowing this extensive and complex processes of acquiring it. Little are the city dwellers familiar with the fact that the water that runs all the time from their taps, involves a large monetary investment, resources and manpower usage. Statistical studies estimate that it costs Rs 16 per litre for this potable water to reach the city, after undergoing the tedious and long process.

While it is true that citizens do pay for this ‘purified’ water in the form of taxes, the trajectory of these water system networks is so perfectly spread in the city that it deserves greater acknowledgement from the people who benefit from it, rather than being merely counted in fiscal terms. This non-renewable source cannot be treated as just another commodity. This apathy among people is a rising concern that needs to be tackled at a war-footing considering the foreseen water crises in different parts of the world. In rural areas, people face a lot of problems to acquire potable water but in urban cities like Mumbai potable water is made available at people’s doorsteps without much hindrance. This water that the inhabitants of the city consume also undergoes the set treatment protocol but it is often used wastefully.

The United Nations has predicted that the next war will be fought over water, such is its scarcity in the world today. However Mumbai seems to have turned a blind eye to this dreadful future and is seen using the non-renewable source in abundant quantities. The populace of the city fails to know the source of this water, the process that it undergoes before it reaches the city, and the money that is invested in this entire process. Then comes a season with less rainfall, followed by a reduction in the supply of water to the metropolis, and life literally comes to a standstill. The city is then forced to keep to its basic needs and control its more wasteful ways. Our history speaks of water charity through water fountains, tanks and wells and it is time for us to take inspiration from them, realise the gravity of the situation and conserve water for our future generations. Passing the tradition of good and potable water is the least we can do; after all we thrive and grow because of it.

References

Maharashtra State, Gazetteers Department. 1909 (Repritned 1977). The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island Gazetteer, Vols 1-3. Bombay: Times Press.

Parab, Vinayak. 2006. ‘Udhalpatti garaj Futpatti Chi’, Loksatta Ravivar Vrutant. Mumbai: The Indian Express Group.

Ranganathan, Murali, ed. & trs. 2008. Govind Narayan’s Mumbai: An Urban Biography from 1863. UK & USA: Anthem Press.

Shirgaonkar, Varsha, S. 2011. Exploring the Water Heritage of Mumbai. New Delhi: Aryan Books.