Memorialising has been a celebrated act in India through architecture, sculptures and monuments to commemorate moments in history. Preserving the memory of the deceased in the form of megalithic burials—non-sepulchral and symbolic in nature—was a tradition practiced all over the world. The prehistoric Stonehenge comprising of stone slabs built in a concentric circle is the best-known example of this. It is also interesting to see societal expressions through forms like rock art, long before words had been shaped and language had evolved. Jay Winter talks of ‘sites of memory’ where ‘commemoration is an act out of a conviction, shared by a broad community’ and hence ‘the moment recalled is both significant and informed by a moral message’. To quote, ‘Sites of memory inevitably become sites of second-order memory, places where people remember the memories of others, those who survived the events marked there’. The trauma and sadness of wars has long been commemorated through various memorials all over the world. This ‘historical remembrance’, a term coined by Winter, can also be seen celebrated through the drinking water fountains of Mumbai, which are colloquially referred to as ‘pyaavs’ (Winter 2010).

This module is an attempt to revisit pyaavs as significant components of the urban landscape, as spaces of pause, rest, vitality and access to a crucial public amenity. It illustrates significant challenges in restoring these structures while revitalising the public realm within which they are anchored. Maintaining the pyaav as its central theme, it portrays the uniqueness of every pyaav and studies the tangible and intangible heritage through various avenues of audio-visuals, photographic documentation and review of previous studies done in this field.

Figure 1. Pyaav opposite Colaba Observatory in Old Navy Nagar, Colaba Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 2. Pyaav opposite the footpath of Metro Cinema, Dhobi Talao. Source: Rahul Chemburkar

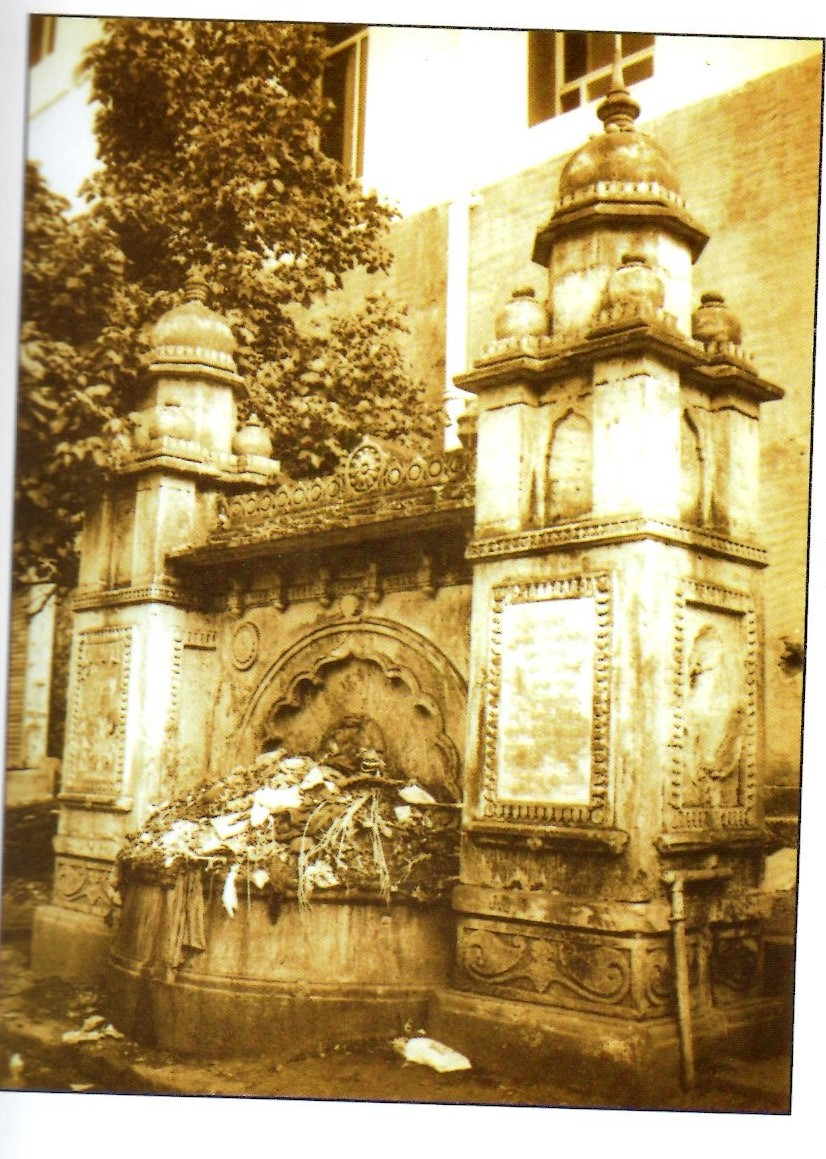

Figure 3. Pyaav in Veer Jija Bai Udyan, Byculla. Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 4. Pyaav in Food Corportation go downs near Reay Road railway station Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 5. Trough of the pyaav at Horniman Circle is also used by people as a resting place. Source: Rahul Chemburkar

Definition and etymology of 'pyaav'

Public water drinking fountains are archetypal structures from colonial Bombay spread across the island city and extending up to today’s Dadar and Sion regions. The more precise time bracket within which these pyaavs were constructed starts from 1865 and ends in 1943. In the early years, one finds a lot of donations for pyaavs, but this starts decreasing from the advent of the twentieth century. Locally they are addressed as ‘pyaav’, which interestingly is a colloquial term, but not rooted in the indigenous Marathi language. Generally, in Marathi, drinking water dispensing units functioning on the similar lines to the pyaav, are known as paanpoi. Some oral histories suggest that the word pyaav comes from the Gujarati language, which was used by traders and businessmen in the city.

Strategic locations of pyaavs

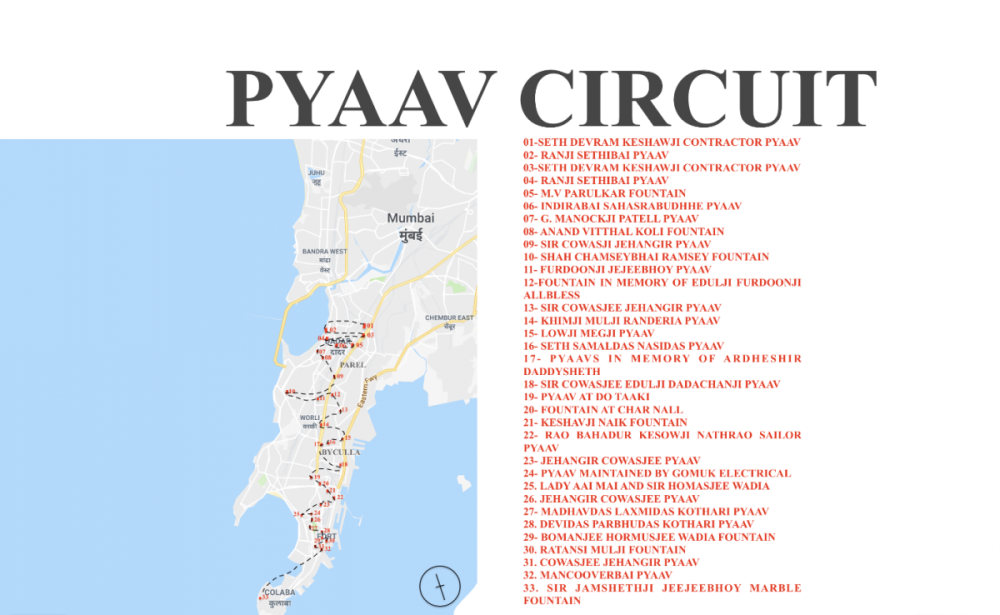

The important aspect is the location of the pyaavs, along the network of old tram routes, traffic islands, busy market areas, and places that witnessed the movement of working class people, day-to-day travellers and transportation of goods on a major scale. The construction of troughs especially is to be attributed to the establishment of markets. Before the splendid Crawford market was built, there were many markets in the island city, like Bohra bazaar, Duncan market, Bori Bunder market and several others. These were en route for pedestrians, horsemen and bullock carts to stop by for a quick rest break.

Additionally, tram services began in Bombay in 1874, when the first horse-drawn tram ran from Bori Bunder to Pydhonie via Kalbadevi (Shirgaonkar 2011). This proliferated the commissioning of pyaavs along these tram routes. Providing water to the people passing was the primary function of these structures, but they also behaved as spaces for pause, where commuters halted, drank water and continued on their journey. The facilities were also a boon for the animals at all these busy areas.

Figure 6. A Pyaav trail from Colaba to Bandra MCGM Ward wise distribution of pyaavs. Source: Vaastu Vidhaan Porjects, Mumbai

Architectural merits

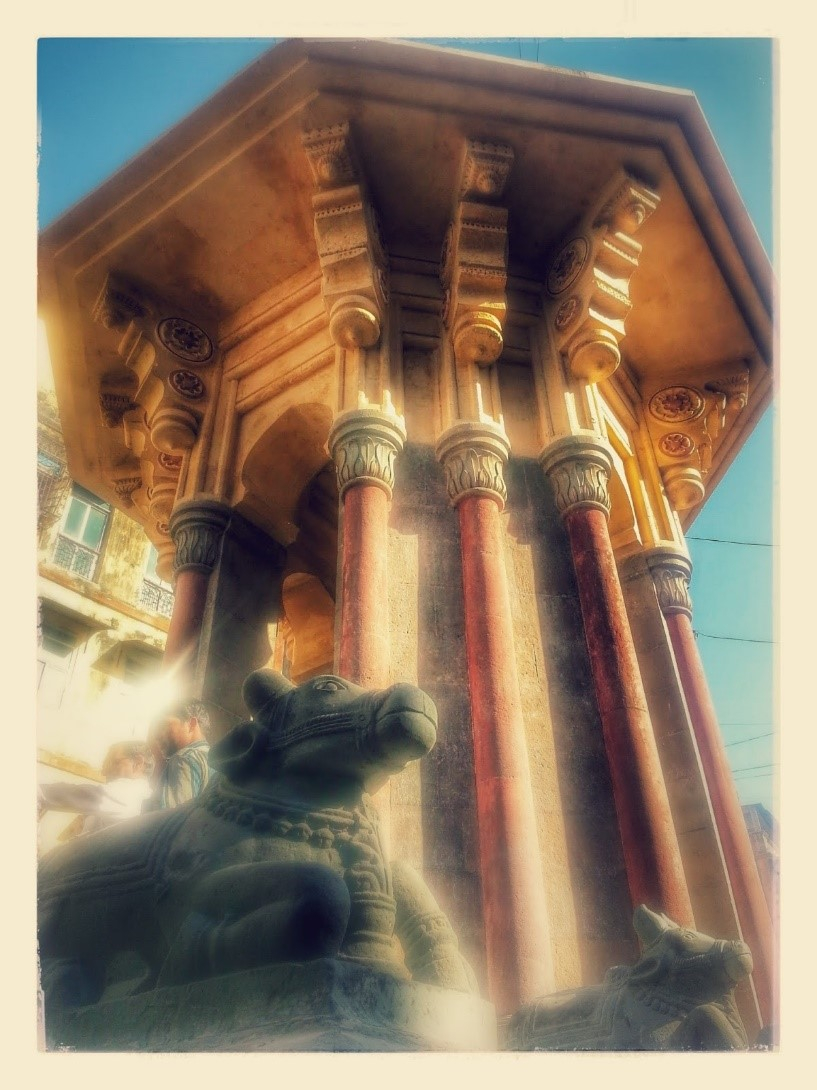

E.H. Carr says that, ‘History is a dialogue between the past and the present’ and architectural traces such as pyaavs are similar expressions that one witnesses in the present. The typology of a pyaav pans over two important facets, one is the morphology of these structures and the other are the adorned embellishments. The quintessential structure consists of water spouts for dispensing water to the people and spill over troughs to quench the thirst of animals. The water was either directly lined up to the spouts through municipal water connections or external water storage tank arrangements were made. Interestingly, the proportions of these monuments range from meagre 5 feet pedestals to 20 feet odd canopies or clock towers, such as the Bazaargate Street pyaav or Keshavji Naik fountain.

Figure 7. Clock Tower Dome of Keshavji Naik Fountain with sculptured panels depicting elephants and peacocks. Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 8. ‘Gomukh’ spout on the façade of the pyaav at Bandra. Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 9. Round arches, Corinthian pillar orders, decorative key stones, faunal depictions on the interiors of the pyaav at Do Taki. Source: Swapna Joshi

The predominant material used for construction is stone, with its type varying across local sources like basalt, trachyte (rock) or Malad stone, Spilyte or Kurla stone, along with imports such as Red sandstone or Porbandar limestone. As part of embellishments, a large amount of flora and fauna is depicted on the pyaav. Lion-heads being used as spouts is one example, which is comparable to some other practices of using gargoyles in colonial buildings or gomukhs in temple water outlets; a common motif despite the varied uses.

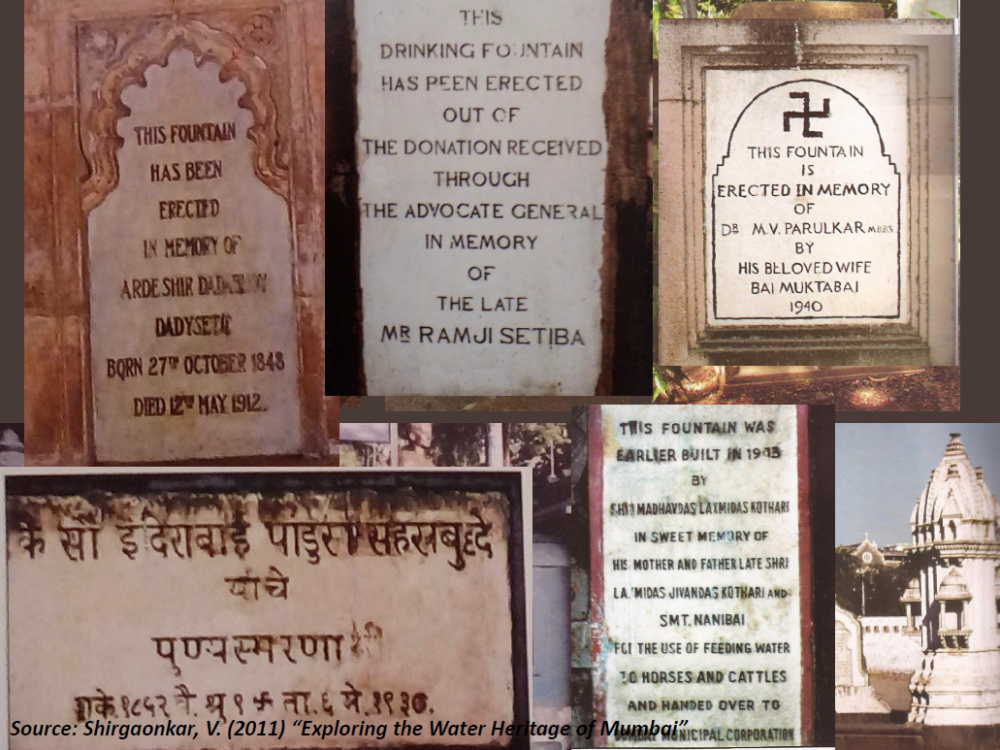

Along with water dispensing, the pyaavs are memorials and this is well established through the plaques embedded in the structures. The linguistic form and palaeography of the plaques are evident mirrors of Bombay. From minarets to foliage patterns, the bust of the patron to animal sculptures, floral motifs to trellis work, relief panels and beautifully carved mouldings, every pyaav has a different architectural style to boast and every architectural piece from the pyaav tells you a different story.

Figure 10. Lion head on the plinth of Mancooverbai pyaav at Horniman Circle. Source: Swapna Joshi

Figure 11. Keshavji Naik fountain with the overlooking nandi on its step guard. Source: Rahul Chemburkar

Water as charity

It was only in the late 1800s that the wealthy started contributing funds to erect such water fountains and had their names embossed on plaques (Satran 2015). Apart from philanthropy they seemed to be motivated by their contributions being a part of posterity. Those commissioning the fountains as memorials did so to memorialise the individual and to depict the person as being monumental rather than the structure itself. Some of the rich Parsi migrants, had close ties with the British. It is possible that some of them might have been inspired to construct these fountains after having seen similar structures in England. One such instance which seems to indicate this influence is the fountain abutting the entrance of St. Thomas Cathedral in Mumbai.

Not all pyaavs were raised in memory of someone; many were constructed just for public use as a result of generous philanthropy by great men of the era. A name to take here would be Sir Cowasji Jehangir, rightly called as ‘Readymoney’, who is credited to have bequeathed forty pyaavs to the city. The Late Mr Ramji Setiba, Furdoonji Jeejeebhoy and Jamshedji Jeejeebhoy are a few others who have contributed to building pyaavs in the city.

Figure 12. Memory and monumentality comes together to establish the roots of patronage patterns that could be studied to understand the history of the structure itself. Source: Varsha Shirgaonkar - Water Heritage of Mumbai

Water as charity seems like a very unusual topic for discussion. Given that water is free, no one ever thinks about how this natural resource could be treated as charity. But ironically ‘giving or serving water’ has always been considered punyakarma (a meritorious act) in Indian tradition. Water has this intangible quality that binds and brings people together. Building commemorative fountains amidst the planned Mughal gardens was a common practice, as also the custom of providing drinking water facilities through haud systems. Bombay’s philanthropists adopted this selfless deed and built hydraulic systems, which could act as immediate suppliers of drinking water. How closely philanthropy and water are associated, can be studied from the style and pattern followed in order to make such systems successful. Unlike today, where you just stop by any store and get packaged drinking water for roughly rupees Ten, back then, water was not seen as a commodity to be purchased or sold. It was not considered an individual’s property but was a universal requirement willingly and mutually shared in the society. The built structure may hold a plaque suggesting ownership, nevertheless, the resource supplied was for all to enjoy and feel satiated.

Conservation measures

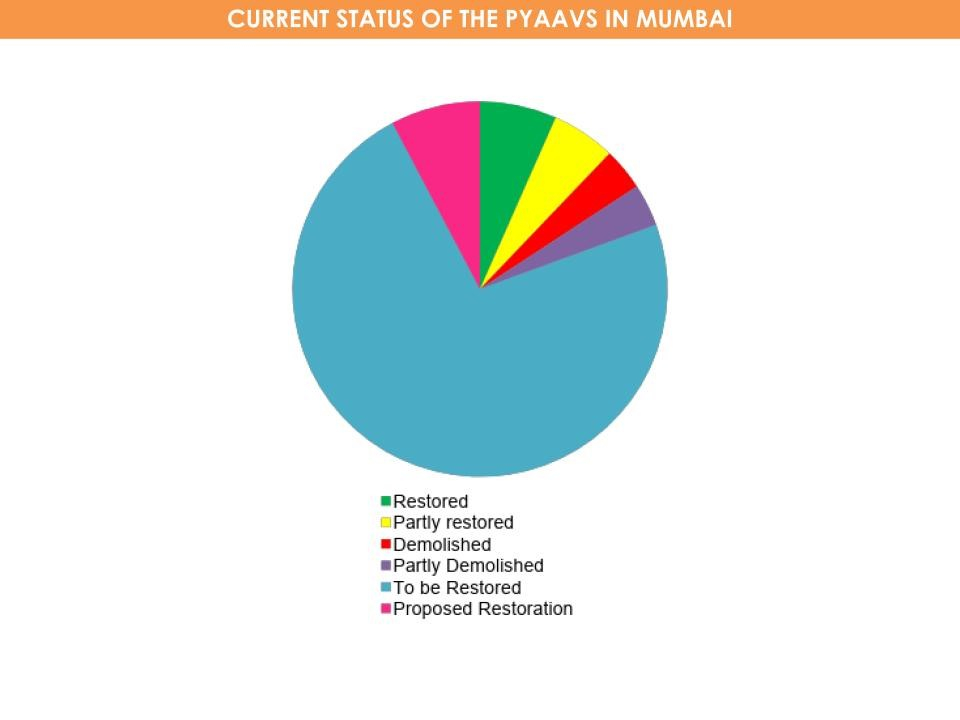

The major point of concern today is the lack of knowledge about the pyaavs of Mumbai. While larger buildings are a matter of concern for many, heritage is also about giving importance to smaller and humble premises. From 1865 onwards, there are roughly some 25 or more pyaavs that can be located in the city, most of which are non-functional today. They are at prominent places of the city where public water facility has and would always be a basic necessity.

Figure 13. Current Status of the Pyaavs in Mumbai. Source: Swapna Joshi

Pyaavs at Veer Jijabai Udyan are a very good example of this. The garden authorities have built new drinking water facilities for the heavy influx of people visiting every day. Reviving the water facility into the historic pyaav would aid the provision of water and would also nurture the heritage in the right way. The tangible restoration of these pyaavs has already happened, now only the hydraulic systems needs to be fixed. This is not just the case with Jijabai Udyan, but also almost all the other pyaavs, as their locations have been well thought of by the inceptors.

Figure 14. Details of pyaavs built in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, restoration works of the twenty-first century pyaavs and pyaavs damaged because of negligence. Source: Swapna Joshi

A quick survey of the history of pyaavs and when they were constructed, as against how many of them have been restored, shows that the difference between the two is very large. Nevertheless, after 100 years, a conservation movement for the restoration and revival of pyaavs seems to have begun. Keshavji Naik fountain from Masjid Bunder and Mancooverbai pyaav at Horniman circle are two fully restored pyaavs in the city with adequate water facilitated through them. Kothari pyaav, Anand Vitthal Koli pyaav, Cowasji Jehangir pyaav at Kalachowki are also on their way to conservation.

But while this is commendable, incidents such as the ruthless demolition of the pyaav opposite Bharatmata theatre in 2010 are grim reminders of the prevailing negligence around these structures. Another example is of the pyaav opposite Shiv Sena Bhavan, which has lost its upper half at some point and only the lower half of the pedestal is lying at the corner of the footpath. One more important pyaav is the one outside Yellow Gate police station. It has been converted into a Ganesha Temple by making necessary changes in the architecture while paying no heed to its original utility of construction. Being a religious structure now it is not prone to damage but sadly no longer functions as a drinking water fountain. It is necessary to strive hard to protect, preserve and cherish these pyaavs and give them back to the city.

Figure 15. Old photo of pyaav at Bharatmata prior to demolition. Source: Water Heritage of Mumbai (2011),Varsha Shirgaonkar

Figure 16. Half-broken pyaav at Dadar near Kohinoor square, opposite Sena Bhavan. Source: Water Heritage of Mumbai (2011), Varsha Shirgaonkar

Figure 17. Pyaav near Yellow Gate Police Chowki. Source: Swapna Joshi

Holistically speaking, the proliferation of such built-forms follows a process. In order to have an upkeep of memory, the narrative began; the materials and method of construction followed were a prototype of the place where it was built, besides the funding in the form of a contribution laid down its evolution which today seems so out of place. Thus, the patronage pattern can be easily understood if this process is in place and traced in advance, in order to take a deeper look at it. To this day, pyaavs stand as an epitome of community that is supplying water to everyone passing by, for free, as it should be. Water dispensing as a charity-memorial, remembering a person by giving something important to society. Restoring these pieces of heritage is not merely to restore monuments but also the value for a rapidly depleting resource, which was once held as sacred. It is to restore the value for an inter-dependent society in increasingly competitive times.

References

Maharashtra State, Gazetteers Department. The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island Gazetteer, Vol 1-3. Bombay, Times Press, 1909, Reprinted 1977.

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai, Official Database through Web Portal

Shirgaonkar, Varsha. 2011. Exploring The Water Heritage of Mumbai. New Delhi: Aryan books International.

Satran, J. 2015. ‘13 Weird Moments in the History of Water Fountains’. January 14. Online at: http://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/history-of-water-fountains_n_6357064. (Retrieved on November 12, 2017).

Winter, Jay. 2010. ‘Site of Memory’. In Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz, New York: Fordham University.