The elephant, one of nature’s most beautiful creations, has always held a unique status in India. The animal is associated with Ganesha who has the head of an elephant. This wild animal has, over millennia, been captured, tamed, loved, and used for various purposes. In certain temples, it is said that the heavy stones used in the gopuras were carried up by elephants, who pulled them up ramps. Kings and chieftains in ancient India employed war elephants and kept them as symbols of prestige. The relationship between humans and elephants thus has a very long history. There is no mention of elephants used in religious practices in the Mātangalīla or Pālakāpyam. Elephants were reportedly used in temples in Tamil Nadu, but as draught animals to carry water to the sanctums and for transportation. However, there is no clear understanding on the origin of the practice. The Thripunithura temple of Cochin Royal family dates the story of processions to a few centuries ago. According to one source, Saint Vilwamangalam had visited and watched a majestic pageant parading 15 elephants. Sreedhar Vijayakrishnan (2015) has traced the history of use of elephants in festivals and he indicates that it began sometime in the 1700s or 1800s. Thus, the use of elephants in temples is around 200–250 years old. The Cochin State Manual by C. Achutha Menon mentions about 12 elephants belonging to the Devaswoms in 1890s. The mention of the crescent-shaped designs on the nettipattam (headgear) of an elephant in Aṣṭamiprabhandhā written by Melpathoor Narayana Bhattathiri (1559–1645) is believed to be potential evidence of elephants in temples in the late 1500s to early 1600s.

In some temples, the deity is carried on the forehead of the elephant thrice a day as a part of a daily ritual called seeveli (colloquial usage for Sreebhutabali). Thus, the deity, positioned atop the elephant, circumambulates the temple three or more times daily, while offerings are made to nature as part of a religious ritual. Tantra Samuchaya is a compendium on the rites of worship practised in the temples of Kerala; it prescribes that in festivals and even daily seeveli, it is customary to carry the deity on a vahana (carrier) which may be human or animal (such as horse or elephant) or vehicle (palanquin or chariot). It is likely that temples preferred using the elephant in seevelis and festivals because it is a beautiful animal whose height increases the visibility of the deity. Its use was welcomed by all and, in due course, it became a tradition.

Kerala has maintained an atmosphere of religious harmony and inter-religious co-operation over centuries. It is not surprising that some churches and mosques have adopted the festival practices prevalent in neighbouring Hindu temples, like elephant processions and percussion orchestras. There are many churches and mosques in central Kerala that use 30–40 elephants in their annual festivals, though in other places the number may be lower.

Kerala has a few thousand temples, churches and mosques, each of which hosts annual festivals. Elephants form an integral part of the festivities in most temples and in a few churches and mosques. In temples, a replica of the deity is placed on a large golden howdah on the forehead of an elephant. This elephant is adorned with fineries designed and produced by artisans to suit the elephant’s face and body. The idol carrier is usually flanked by other decorated elephants, forming a beautiful pageant. A percussion orchestra—such as the panchavadyam (orchestra of five instruments of which three are percussion, one is wind, and the other a pair of cymbals) and nadaswaram (a wind instrument)—moves in front of the pageant. Specific drum concerts are prescribed for different days and occasions in temple festivals, depending on the deity and the place of performance. The pageant and the orchestra move through set routes within and outside the temple premises.

Because of their constant use in temple festivals, elephants are considered a part of life and society in Kerala. For Keralites, elephants are not wild animals; loved and adored, they are their own kith and kin. When elephants are an integral part of a celebration, people gather in thousands to witness the show and enjoy the accompanying orchestra. There are different kinds of orchestras associated with festivals; in north Kerala, drum concerts (melam) are more common than panchavadyam; in central Kerala, drum concerts and panchavadyam have almost equal importance; and in the south, nadaswaram performances are preferred.

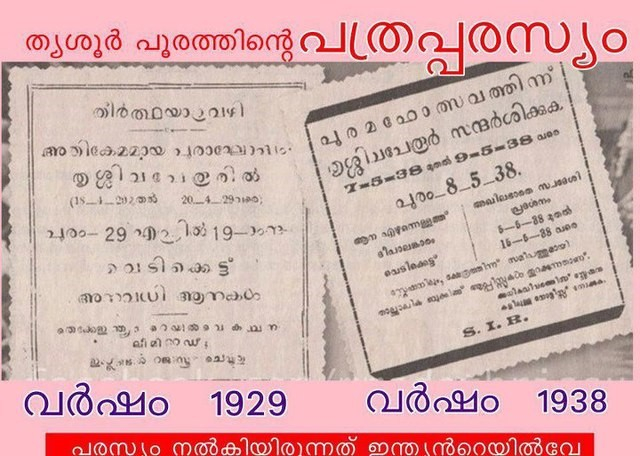

Of the thousands of festivals in Kerala where an elephant parade is an important feature, Thrissur Pooram is the most enchanting. The most popular events of Thrissur Pooram are the divine durbar and the pyrotechnic display. The divine durbar is held in the evening hours of the Pooram day in the ramparts of the south gopuram of the Vadakkumnathan Temple. Fifteen finely decorated elephants from Thirivambady Sree Krishna Temple and Paramekkavu Bhagavathy Temple are aligned in rows, standing face-to-face, 100 meters apart, amidst an ocean of people. The silk parasols atop the elephants are changed every minute, colour after colour in quick succession; peacock feather fans are held aloft and yak tail flywhisks are waved to the tune of the accompanying orchestra. This scene has not been emulated elsewhere in the world. The topography of the southern gopuram also plays a crucial role in creating this spectacle

The well-known Guruvayur Sree Krishna Temple started taming elephants 200 years ago; the first elephant reared at the temple was a makhna and it helped in carrying the stones for the construction of the base of the temple flag post. The second elephant of the temple was the famous Padmanabhan; available records show that this elephant was paraded during Thrissur Pooram 140 years ago by the Thiruvambady Devaswom and the deity was carried by this elephant during the famous Madathil Varavu. The legendary elephant Guruvayur Kesavan was part of temple activities from 1922 to 1976.

The ritual of Anayottam (elephant race) at Guruvayur temple attracts a large crowd of devotees and spectators. Local lore tells that this ritual has its roots in a rivalry between the Zamorin of Calicut and the Raja of Cochin—the legend goes that the Guruvayur temple, part of the Calicut kingdom, did not own any elephants and so had to borrow them from the Trikkanamatilakam temple, under the King of Cochin. A misunderstanding between the authorities of the two temples led to an elephant not being sent to Guruvayur as scheduled. On the day of the festival, the elephant tethered at Trikkanamatilakam temple broke its chains and galloped all the way to Guruvayur Temple so that the ritual could be conducted successfully. It is believed that Anayottam is conducted to symbolically commemorate this event on the first day of the annual festival.

The Guruvayur temple is known for its strict adherence to tantric rites and unique rituals. The presiding deity in the central shrine (garbhagraha) is Maha Vishnu, worshipped and served by specific puja routines laid down by Adi Sankara. These rituals include seeveli in the morning and evening and athazha seeveli at night. During seeveli, the sreekovil (sanctum sanctorum) is opened, allowing the devotees to have darsan. The procession of seeveli symbolises the deity watching over the wellbeing of all entities of the universe.

Arattupuzha Pooram, Kerala’s oldest known festival where about 100 elephants congregate, is believed to have had its 1,436th edition in 2018. Other temple festivals held around Thrissur where elephants form an important part are the Koodalmanikyam temple festivals, Uthralikkavu Pooram, Thriprayar Ekadasi, Guruvayur Utsavam, Kodungallur Thalappoli, Chembuthara Makarachowa, Peruvanam Pooram and Anjoor Parkkadi.

Other festivals famous for elephant parades are Nenmara Vallangi Vela, Chinakkathoor Pooram, Thattamangalam Angadi Vela, Manappullikkavu Vela, Poornathrayeesa Festival in Tripunithura, Ernakulam Shiva Temple Festival, Vaikathashtami, Thirunakkara Temple Festival of Kottayam, Ithithanam Ulsavam, Ettumanoor Temple Festival, Ayiramkanni Bhagavathy Temple Festival, Paripally Kodimootil Bhagavathy Temple Festival, Asramam Sreekrishna Swamy Temple Festival, and the Aaraattu Festival of Thiruvananthapuram. On the Bharani asterism of the Malayalam month Kumbham, grand festivals are held fielding 7–11 elephants across 19 Bhagavathy temples in Thrissur district. Churches and mosques also have festivals that involve the participation of many elephants, among these the Adupputty Palli Perunnal or Church in Kunnamkulam is the foremost. The Pattambi Nercha, Manathala Nercha and BP Angadi Nercha mosques are also notable for their elephant parades. In most Kerala temples, there is no festival that does not engage at least one elephant; it is only the number of elephants engaged that varies.

In Kerala, elephants were owned and maintained largely for their use in festivals, but some elephants were also used for timber logging. Elephants to be considered prestigious symbols of affluent families and devasthanams (divine centres like temples). They took meticulous care of their animals—periodic oil baths; body rubs with coconut fibre (chakiri) and soft granite stones; food including palm-leaf fodder, grass and cooked rice; Ayurvedic medicines, and so on were provided regularly to elephants. The mahouts were trained to love the elephants as their own children. An annual tonic treatment after the festival season has also become a regular feature of elephant care.

In recent times, inflation has begun to affect these practices. Yet, festival-goers are keen that the objects of their adoration are looked after well. During festivals, organisers and well-wishers provide pucca sheds and cool green cover for the elephants who have to stand for long durations; they pour water on the path along which the elephant procession passes in order to keep it cool; and spread wet gunny bags on the ground for elephants to place their feet. In addition, they provide them with a regular supply of delicious foods like cucumber, watermelon, pineapple, and so on, to satisfy both thirst and hunger. They also give elephants tethered for long hours, pieces of palm leaf fodder and enough water for drinking and bathing during the free hours of festivals.

Owing to recent restrictions on the capture, sale, purchase, and owning of elephants, festival lovers in Kerala have begun to feel anxious that these pageants may soon fade to oblivion. Since the number of captive elephants is reducing, those available are overworked during the five-month festival season. The new practice of transporting elephants in trucks is inadvisable—the stress induced may cause the animals to suffer gaseous blocks and impaction. This mode of transportation must be restricted to a reasonable duration and distance on a given day. Additionally, the elephants must be made to walk at least 5–10 km a day, with variations according to their age, size, and health. To reduce the period of musth, male elephants must not be given medicines during this time.

Elephants must never be considered a commodity; they are to be looked after as our own. In the old days, the mahouts were well trained in traditional methods as envisaged in the Gajasastra, compiled by Maharshi Palakapya. It is believed that the maharshi lived with elephants in the forest for decades before he compiled his observations. His book became an authentic record on elephant behaviour and treatment—it is recognised by elephant experts all over the world. Now, as a result of excessive commercialisation and increased demand disproportionate with supply of captive elephants, both the condition of these animals and their relationship with their mahouts have worsened.

Temple festivals are an integral part of cultural life in Kerala and are attended by people from all walks of life marking the historic communal harmony of the state. Each festival is the result of ancient beliefs developed by our ancestors who abided by rituals and rites. A decline in this will be tantamount to the destruction of the rich tradition for which India is famous.

Bibliography

Vijayakrishnan, Sreedhar. 'The Elephant in the Room – I.' India Facts. November 24, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2019. http://indiafacts.org/the-elephant-in-the-room-i/