In this edition of ‘Lore and Life’, we look at the history of Holi, the various myths, traditions and rituals associated with the festival, and how the festival was used in the Indian independence movement (In pic: A 19th-century painting of a prince playing Holi in his harem from the National Museum, New Delhi; Photo Source: Google Art Project/Wikimedia Commons)

In the cluster of festivals and rituals around the equinox worldwide, India’s share is plentiful, and Holi would be primary. It appears that for thousands of years, civilisations around the world have recognised the arrival of spring and the change of season in the third week of March after the full-moon day, and the arrival of equinox—when day and night are almost equal in length across the world. This is because the sun is positioned above the equator during the equinoxes, and world civilisations marked the day as the day of new beginnings.

The Persian New Year, Nowruz, starts on this day; early Egyptians built the Great Sphinx in such a way that it points directly towards the rising sun on the equinox; and many sects of Christianity consider Easter as the New Year that usually falls on the first Sunday after the March full moon. Ancient and medieval Indian literature refers to the festivals of this season appropriately as Vasantotsava (celebrations of spring) and describe them at great length since they were major events of their times. The spring festival is called Yatramahotsava of Madana in the Sringaram Harikatha, the Kamamahotsava in the Kavyaviveka, the festival of Madana in the Ratnavali and Bhavishya Purana, and Madanotsava in Bhavaprakasha.

Also See | Holi: A Celebration of Colours (Photos)

As names such as 'Kama' and 'Madana' indicate the arrival of spring, the festival is perceived and equated with the heightening of love and lust in humans, and fertility and regeneration in the vegetation and animals. Anthropologists have often identified spring festivals as fertility rites and Holi is a prominent example.

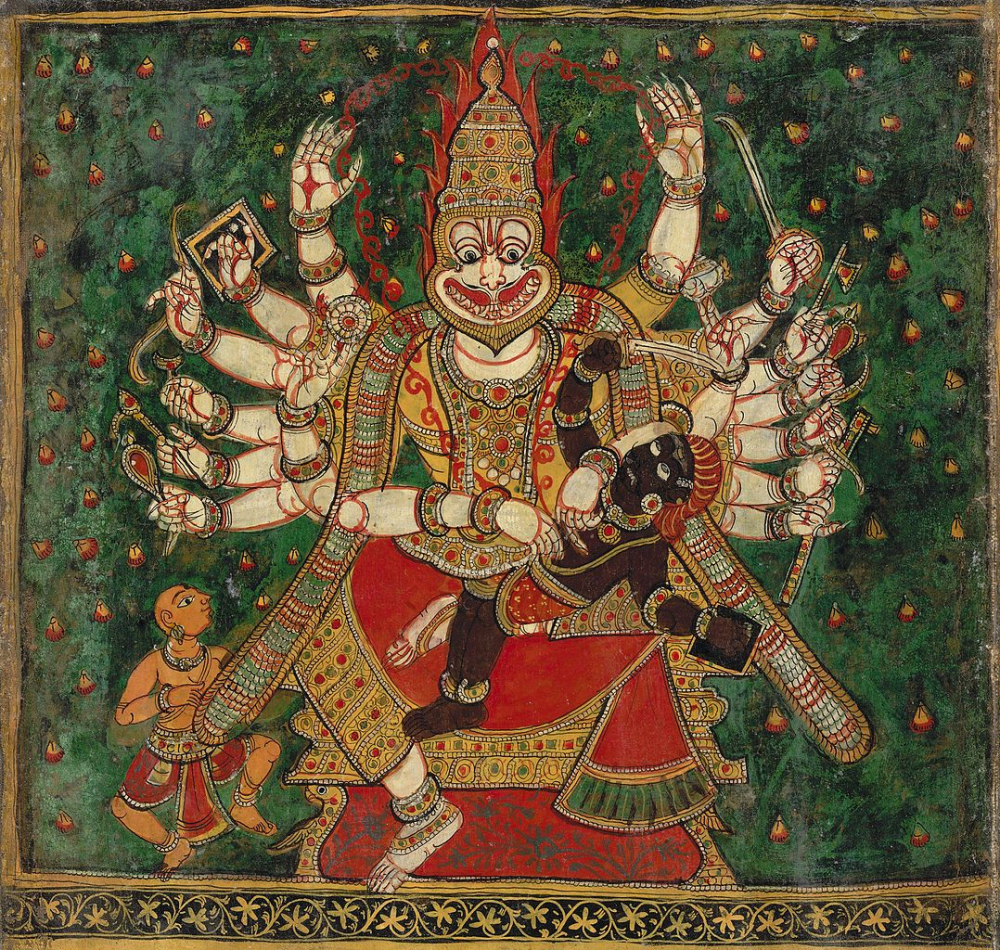

An 18th-century oil painting depicting the mythological story of Narasimha killing Hiranyakashipu, with Prahlad as witness. The story of Holika (Hiranyakashipu's sister) sitting in burning fire with Prahlad is one of the most popular myths associated with Holi celebrations (Photo Source: British Library/Wikimedia Commons)

Interlocking Mythologies

Wild behaviour, a liminal period of breakdown in social hierarchies, and definite overtones of sexuality and intoxication characterise fertility rites and festivals, and the behaviour of Holi celebrants has enacting references to at least two interlocking mythologies among many. As Kamamahotsava, Holi is believed to be the day Lord Shiva opened his third eye and burned down Manmata—the god of love—into ashes. The Kamamahotsava used to be celebrated in Tamil Nadu on the fifth day after Pongal with explicit references to the Shiva mythology. Lavani was a Tamil folk performance in which participants would divide themselves into two opposing parties that sing, dance and debate endlessly whether the god of love can be burnt down or not. Now these celebrations and the form of Lavani have become extinct in Tamil Nadu, but their north Indian counterparts exist vibrantly as part of Holi celebrations.

Also Read | Bhagoria and Yaoshang Festivals: Exploring Holi's Different Colours

Setting up of a huge bonfire on the night of the full moon to mark the beginning of Holi celebrations in the villages of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar refers to the act of Shiva burning down the god of love. However, as mythologies cross-fertilise and envelop ritual acts, the bonfire has other references as well. In the mythology of Narasimha (Vishnu’s avatar), Holika, the sister of Hiranyakashipu, took Prahlada on her lap and sat on a pyre to save him and the devotees of Vishnu were unharmed. Many anthropologists report that Holika was the saviour of Prahlada and a devotee of Vishnu, and the festival is named and celebrated to honour her.

However, the contrary version about Holika is popular among the participants of Holi. According this version, as Prahlad was not hurt by all the attempts on his life, Hiranyakashipu called upon his sister Holika, who had a boon from Lord Brahma that she could not be burnt by fire. Holika made Prahlad sit on her lap in the fire, with the intention that he would burn to death. But the scheme failed, and Holika was burnt to death and Prahlad was unhurt. In the cultural region of Braj, where epicentres of Holi such as Mathura and Vrindavan are located, the festival has come to be associated with the divine love of Radha and Krishna.

Holi festivities in Barsana. The diverse ways in which Holi is celebrated across north-western Indian states share these role reversals and the centrality of women as the core of their celebratory activities (Photo Source: Narender9/Wikimedia Commons)

Carnivalesque Churning of Social Hierarchies

Participating in the Holi celebration in a village called Kishan Garhi, located across the Yamuna from Mathura and Vrindavan, a day’s walk from the youthful Krishna’s fabled land of Braj, American anthropologist McKim Marriott observed in his essay ‘The Feast of Love’:

The dramatic balancing of Holi—the world destruction and world renewal, the world pollution followed by world purification—occurs not only on the abstract level of structural principles, but also in the person of each participant. Under the tutelage of Krishna, each person plays and for the moment, may experience the role of his opposite: the servile wife acts the domineering husband, and vice versa; the ravisher acts the ravished; the menial acts the master; the enemy acts the friend; the strictured youths act the rulers of the republic. The observing anthropologist, inquiring and reflecting on the forces that move men in their orbits, finds himself pressed to act the witless bumpkin. Each actor playfully takes the role of others in relation to his own usual self. Each may thereby learn to play his own routine roles afresh, surely with renewed understanding, possibly with greater grace, perhaps with a reciprocating love.[i]

The women of Kishan Garhi identifying themselves with Radha to feel the empowerment of role reversals during the festival time is not restricted to that village alone, but is an all-pervasive phenomenon of Holi. The diverse ways in which Holi is celebrated across north-western Indian states share these role reversals and the centrality of women as the core of their celebratory activities.

Also See | Holi in Vrindavan: A New Beginning (Photo Essay)

Interpretation of Holi as the carnivalesque churning of social hierarchies has not gone unquestioned in recent times. Reporting on the celebrations of Holi in Charthari village in Uttar Pradesh, Sanjay Tiwari detailed how the Dalits and women bear the brunt of the hard work that goes into celebrating Holi but are not permitted to participate in the enjoyment.[ii] Observing Holi celebrations at the Dauji temple in Baldeo, Uttar Pradesh, where Krishna’s brother Balarama is given more importance than Krishna, A. Whitney Sanford writes in her essay Holi Through Dauji’s Eyes:

Balarama’s role does reaffirm hierarchies, to a point, but he also transforms hierarchies by reinterpreting some of the factors that have made him—in some eyes—subordinate. So, for example, in some Vaishnava eyes, maryada is a subordinating element. Balarama, however, redefines maryada—and turns it upside down—by its linkage with bhang, sexuality and aggression. In this system, there is much less room for the capricious antics of Krishna.[iii]

The transformation of Holi celebrations into affirmations of social hierarchies, and the strengthening of the meat and muscle power of high caste males must have occurred with the infusion of nationalistic fervour in the festivities. Nandini Gooptu, in her book The Politics of the Urban Poor in the Early Twentieth Century India, outlines a brief history of Holi’s transformation from a religious festival into a festival of nationalistic freedom struggle. Identifying Lord Narasimha’s killing of the evil demon ruler Hiranyakashipu as the reason for the celebration of Holi, Gooptu presents an array of data to prove how the festival was projected as a metaphor for liberation from evil British rule and domination. In the 1920's and 1930's, from being the festival of the poor, Holi emerged as the festival of the bazaars. Gooptu further writes:

(B)y the mid-1920s Holi had come to be celebrated over a period of seven days in the Kanpur bazaars and police reports mentioned the new innovation of celebratory processions during Holi. By the mid-1930s, the District Magistrate of Kanpur was issuing restraint orders during Holi to control what he saw as 'hooliganism' and excesses. Hooliganism and political uses of festive mass gatherings continue to haunt the celebration of Holi in several cities and rural pockets even today and police issues warnings of action against miscreants well ahead of Holi every year.[iv]

Holi is also a merchandise to be sold to the traditional participants living outside the inherited contexts of its celebrations. While the history of throwing and smearing coloured powders and sprinkling water on everyone you meet is not yet fully known, it is marketed as a fun ticketed activity inside the theme parks of new urban areas in the South Indian cities. Some of the marketers of Holi even invoke the mythology of the ogress Dhundhi—who could be frightened away by the taunts of children—to entice the children to hoot, shout and have fun in celebrating Holi.

Participatory and diverse, the charm of Holi celebrations continues to be the possibility of throwing colourwd powders in the faces of authority figures and establishing a temporary egalitarian utopia.

Views expressed are personal.

[i] Marriott McKim, ‘The Feast of Love’, in Krishna, Myths, Rites and Attitudes, ed. Milton Singer. Honolulu: East-West Centre, 1966, 210–12.

[ii] Sanjay Tiwari, ‘An Unholy Festival’, Economic & Political Weekly, XLVIII, no. 21 (2013).

[iii] A. Whitney Sanford, ‘Holi Through Dauji’s Eyes’, in Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, ed. Guy L. Beck. New York: SUNY Press, 2006.

[iv] Nandini Gooptu, The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early Twentieth Century India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.