Origin, ethics and closeness to nature

As in most pre-industrial societies, the geographic and topographical features of Rajasthan exerted a significant influence over its socio-economic conditions. The Aravalli hills divide Rajasthan broadly into two natural divisions: the north-western and the south-eastern. In the northwest lie the arid plains and shifting sand hills of Marwar, Jaisalmer, Bikaner, and the Shekhawati region of Jaipur, collectively bearing the term Maroosthali (Sanskrit: ‘Land of the Dead’) comprising the eastern portion of the Great Indian (Thar) Desert in western Rajasthan and north-western India. It extends over about 24,000 square miles (62,000 square km), north of the Luni River. This region is characterised by low ridges and sand dunes: ‘…The region is full of dust storms. It is such a desolate desert that if a newcomer misses the path, he is lost forever and dies’ (Nainsi 1657-1666, 1962: 31).

Rajasthan’s landscape encourages dependence on agricultural and livestock-rearing practices. The natural vegetation of the region helped sustain superior breeds of cattle for export to agricultural zones of other regions—sheep for wool, and camels for transport. Trade and commerce was also an important component of these economies as is evident in the nature of taxation where non-agricultural production was also taxed extensively (Kumar 2005).

In the protection of natural resources, rulers also imposed fines on different kinds of illegal usage of natural resources. For instance, the felling of green trees or defacing the village pond through use of dyes were subject to penalty. It is, however, not clear from the available records which official imposed or collected the fines but their enforcement was evidently commonplace (Kumar 2005:138).

The social concern for the environment in medieval Rajasthan manifested itself in various forms. Apart from taxes, they had a pride of place even in the teachings of sects like the Jains and Bishnois. The founder of the Bishnoi sect, Jambhoji (1451-1536 AD), prescribed 29 rules for his followers. Many of these suggested maintenance of harmony with the environment, such as the prohibition on cutting green trees and animal slaughter (Maheshwari 1970; Kumar 2005). Community norms on the maintenance of sacred groves, or orans as they are called in Rajasthan[i] have also ensured the upkeep of green areas in the arid regions of the state (Khanwalkar).

The Bishnoi community—A general introduction

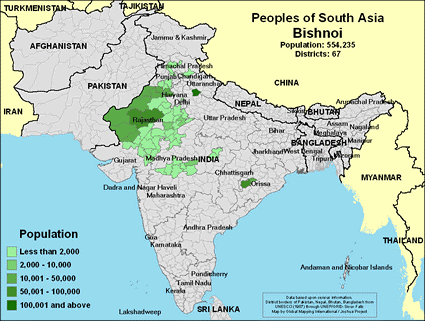

Out of the total population of India (approximately 1.271 billion), the Bishnoi count stands at 600,000 nationwide approximately and is estimated at 32,600 in Rajasthan.

Distributed in several north Indian states, Bishnois are concentrated in western Rajasthan, where their founder Guru Jambheshwar was born (Jain 2010). Living both in rural as well as urban areas of western Rajasthan, Bishnois defined themselves as a sect of Vishnu worshipers with intense devotion to nature. They typically own varying amounts of land, are settled pastoralists, and practice a variety of professions such as farming, selling milk, working with the forest departments and the police, dealing in property and transport to being bureaucrats, leaders and teachers (Census 2011).

Fig. 1. Source: https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/16464/IN. Retrieved January 12, 2018

Their eco-friendly ethos (even in the death rites) not only ensures environmental frugality but lends them credibility as grassroots environmentalists. As teetotalers, they practice simple lifestyles. Known for their proclivity for letting bushes, shrubs and foliage grow in the fields, Bishnois manage to protect the desert sand from wind erosion. They provide the much-needed forage for cattle during the hot dry season or a famine. Nonetheless, many observers caution that the Bishnois cannot be eternally safe from the impact of detrimental ecological practices (Shivraj Bishnoi, personal interview, July 19, 2017). Hence, contemporarily, the community remains very active in efforts to save the environment in all ways possible.

Although Rajasthan is typically known for its association with vibrant colours that reverberate across its architecture and attire, each community has developed specific colour codes. Bishnoism, for instance, despite its association with Jodhpur, prohibits the use of blue colour to curb the overuse of indigo (made from cutting huge amounts of green shrubs) as well as in the belief that the colour absorbs the harmful rays of the sun and is associated with death or wrong doings. The customary attire for men is white in colour, which is ideal for the hot dry desert climate. It consists of a kurta, a dhoti, and a safa (turban) to adorn the head. Women wear colourful cholis that have a special yolk to give a perfect body fit, and ghagra (long ankle-length skirts) (Devi 2012).

Paying special attention to cleanliness in their houses, Bishnois often live in little hamlets called dhanis, with just a few round huts with intricate thatched roofs. They scrub the floors of the huts and the common courtyards, and cook in earthen ovens. The mud floors are plastered with cow dung to keep vermin away. The interiors are airy and clean. Men, women and children exude good health. There is a granary to guard their rations and a sump for stored water. Inspired by early environmental prudence towards all living beings, Bishnois, apart from protecting animals, also protect the khejri (Prosopis Cineraria) tree. Their tough existence made them realise early on that the khejri tree is not only their only source of supplementary food but also abundant fodder for their cattle (Deb 2012).

Formation of the Bishnoi sect—Debates, diversities and closeness to nature

Diverse viewpoints on the formation of the sect, its composite culture and its spirit of nature conservation have incited prominent debates over the spread and the religion of the Bishnois. Maheshwari, who has written on the sect extensively, calls them a Hindu sect formed in areas of Jhangaloo, Pipasar and Mukam in what is now known as Rajasthan (erstwhile Mewar/Marwar). Bishnois spread to northern India, especially in select pockets between Rajasthan and Punjab such as Barmer, Naguar Bikaner, Jodhpur and Ganganagar.

There are others as Khan (2003), who argue that the Bishnoi traditions and rituals actually reflect a Muslim state of being (during the origin and founding of the sect) as they not only remain away from idol worship but also bury and not cremate their dead. Jain (2010), however, shows how Bishnois vehemently oppose any Islamic identity. At the same time, he suggests that the ‘Hindu-isation’ of the sect can be understood in the context of the parallel processes taking place, with several other communities possessing liminal/transitory identities—of conversions, origin as well as categorisations (Jain 2010 and 2011) as elaborated below.

The Bishnoi sect can be understood incisively if it is taken as a combination of the old and the new, forming a unique synthesis of transitory ideas.[ii] Historically, the origin of the sect coincided with (some) philosophies of the saints pertaining to the Sufi movement (which preceded it) and the Bhakti movement, which remained strongly influential during the period of the founding of the sect.[iii]

The interaction between early Bhakti and Sufi ideas alongside the previous influences of Jainism and Buddhism in the region laid the foundation of a wider variety of social formations in the 15th century. The Bishnoi sect was one such formation. This helps us understand the syncretised religious and social features of the Bishnois which, to borrow Turner’s (1967) concept, may very well be reflective of ‘social’ liminality. Evolving in a difficult period of Indian history, the Bishnoi sect found a new identity in their ecology-inspired religion.

While crossing the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, one sees that areas inhabited by Bishnois have well-functioning traditional water harvesting systems. There is normally plenty of food. Despite the difficult environmental conditions, millet, wheat, carrots, radishes and sesame oil is produced. Wild fruits and vegetables play an important role in the diet and their cultivation methods are adapted to the local conditions and environmental customs (Botanist Saraswati Bishnoi, personal interview, July 28, 2012).

The Bishnois pay special attention to hygienic practices and environmental sanitation at home as well as in the courtyard. Harvesting rainwater through underground tanks called ‘tankas’, they use the water for drinking and cooking purposes. The cattle are allotted a separate compound adjoining the house. Finally, Bishnois bury their dead in order to protect vegetation in the desert as it is limited.

According to folklore and vernacular literatures, Jambhoji (as the founder was popularly called) had an uncommon attachment to nature. However, in scholarly works on him such as Rose (1997), his environmental inclination is thought to be nothing very distinguishable from the voices of the other Hindu-Jain sects of those times. In doing away with the pheras (the ritual of taking three to seven circles around a holy fire under the guidance of a priest to make the marriage ceremony complete), cutting the choti (scalp-knot/lock) or in the special mode of initiation and the disregard for Brahmanical priesthood, for example, there are indications of the same spirit that moved many Hindu reformers of the era.

Guru Jambheshwar, the founder of the Bishnoi sect and his 29 tenets

The Bishnoi sect was formed by Guru Jambheshwar in the aftermath of a severe drought in Marwar (erstwhile Rajasthan) region of north-western India in 1485 AD. The Bishnois considered that their guru was a reincarnate of Vishnu. Most of the origin myths about Jambhoji and the development of the Bishnoi community emerge directly from their relationship with the land (Reichert 2015:53). Guru Jambheshwar gave a set of 29 principles to be followed as edicts of day-to-day life. The sect's religious philosophy was written down in the form of poetic literature and is available in a compilation called Jamasagar (it elaborates rules and advices for a just, humane, non-violent, truthful, simple as well as vegetarian lifestyle). On the basis of such an origin and its associated belief system, the Bishnois came to form a distinct religious sect (Bishnnoi and Bishnoi 2000; Chandla 1998; Dalal 2014; Tobias 1988).

The name ‘Bishnoi’ (or Bish-Noi, i.e. twenty plus nine)[iv], represents the number of principles espoused by Jambheshwar. Born in 1451, he is said to have practiced a spiritual engagement towards social and ecological problems of his times even in his youth. Despite being born a Kshatriya, the second highest in terms of Hindu caste hierarchy, he disapproved of the caste system and desired to create a casteless community into which all were accepted. Advocating the worship of Lord Vishnu, Jambheshwar strictly prohibited animal killing and cutting of trees.

Some say that being disenchanted by the struggles over political power between Hindus and Muslims, he sought ways not only to reconcile them but also to put before them an example of a heightened moral sensibility; others suggest that a long period of drought moved him to seek protection for all animals and plants (Lal 2005). Negating none of the two, learning as well as borrowing from contemporary Hindu and Muslim cultures, the Bishnoi faith formulated an innovative concept of humaneness. This philanthropic as well as ‘green philosophy’ appealed, or was devised to appeal, to the people’s perceptions in and around the Marwar region.[v]

In 1485, Jambheshwar founded the Bishnoi Sampradaya (a sect) in Sambarthal (located on a sand dune called Samrathal Dhora in a town called Nokha) near Bikaner in western Rajasthan. Regarded as a great saint, he preached love for all living beings through his ‘shabads’ (sayings) which are known to be 120 in number and are available as ‘shabadvani’.[vi]

To be a Bishnoi, the exclusive requirement was to live by these 29 life principles including no killing or eating of animals, no cutting down of ‘living’ trees or their ‘living’ (i.e., green and growing) parts and no alcohol consumption. All castes and communities, who agreed to abide by these rules, were welcome to join the sect.

After Jambhoji’s death in 1532, his shabads continued to draw many supporters and followers (Bishnnoi and Bishnoi 2000; Chandla 1998; Dalal 2014: Chapter J; Tobias 1988). Jambheshwar’s rules and scriptures were meant to be seen, read, recited equally by one and all and were also equally applicable for all who came into Bishnoism or were born into it.[vii]

The 29 principles of the Bishnoi sect

Of the 29 principles laid down by Jambhoji as fundamental for the sect, eight were prescribed to preserve biodiversity as much as to encourage animal husbandry. These include non-sterilisation of bulls, prohibition on killing of animals and birds as much as the cutting of any green trees. Ten principles deal with personal hygiene and health for all. These mention simple tenets like vegetarianism, safe drinking water (cloth-filtered water), bathing daily, environmental sanitation, prohibiting the use of tobacco, opium and alcohol. Four principles provide guidelines for worshipping god daily and to always remember that god is omnipresent. On every Amavasya (new moon), a fast should be observed and a collective lighting of holy fire is to be performed for the salvation of the soul. In Bishnoi temples, idol worship is discouraged. Ritual prohibition for 30 days after childbirth and five days during menstruation are observed. Seven principles describe directions for healthy social behaviour. These direct the followers to live a simple truthful life, be content, be abstentious, avoiding false arguments. Criticising others is strictly prohibited. The principles also call for tolerance during discussions.

This module explores the extensive work on conserving wildlife and natural heritage undertaken by the Bishnoi community of western Rajasthan. This module will acquaint readers with the cultural symbols and ethos of the Bishnois who remain keenly ritualistic and aware of the need to protect the environment and ecology. Alongside documenting the everyday practices and rituals of the Bishnois and their close association with flora and fauna, the module will tackle the case of emerging environmental activism from among the community.

Customary practices of the Bishnois: A close knit social formation

Even though, in everyday perceptions of the self, Bishnois actively define themselves as a caste-neutral Hindu sect[viii], it is relevant to state that some of their practices work in the ways of caste-formulated living. While it is a well-recorded fact (refer to the debates above) that the sect disassociated from the caste system[ix] and considered it as a discriminatory social evil that they would opt out of[x], yet they did not leave Hinduism per se. Bishnois are an endogamous community and maintain clan exogamy. There is a tendency to marry within those who converted from the same stock, i.e., Jat, Chauhan, Bania, etc. (Singh 1990:189).

Bishnois trace their descent from eight endogamous sections, namely, Jats, Baniya, Brahman, Ahir, Sonar, Chauhan, Kasibi and Seth. These castes correspond to the social category that the original member and/or convert belonged to and do not define set social-discriminatory boundaries in day-to-day life within the sect. That these castes represent a mix of ‘high’ and ‘low’ social divisions holds great significance. However, even though the sect maintains the same rules for all Bishnois, they still carry over the gotra system from the ‘caste’ scheme of social life.

Other features such as endogamy (though exceptions have begun to appear), restrictions on commensality and heredity are important characteristics of caste as a social formation and Bishnois are known to abide by these. A gotra exogamy means that they do not marry into any family so long as any tie of a relationship is remembered (Blunt 2004:134). In the rules governing birth and marriage ceremonies, they practice the Hindu system of gotra identification at the time of name-giving and marriage.[xi]

Bishnois were once upon a time an open group and hence the rule of hereditary allegiance was still not the only way to become a Bishnoi. One could convert to Bishnoism. By the early 20th century, however, the Bishnois as a sect had stabilised, as V.V. Bishnoi (a judge by profession), S.R. Bishnoi (scholar), J.S. Bishnoi (politician) from Jodhpur analysed for me during a group discussion in July 2012. One does not hear of conversions anymore. However, the sect remains open to welcome those who abide by its 29 principles.

Besides rituals of baptism and gotra, imitative/derivative from the Indian caste system, the other factor is the practice of restrictions on commensality or intermingling/socialising with other castes, and accepting food and drink from people from other, especially, lower castes, so to say. While the practice is now waning in urbanised contexts, the very orthodox among the Bishnois, even until now hesitate intermingling with people of a lower caste status.

With regard to death, the Bishnois consider it as loss of manpower and hence on the third day of death in a family, a child marriage was to be solemnised in each such household. Together with practices such as child marriage, the restrictions on interaction with non-Bishnois and illiteracy were for a long time the bane of the community. But now these seem to be receding. In recent years, owing to education and awareness as well as a spirit of integration with the larger political context, the Bishnois have been pushed towards self-introspection. So the progressive members of the community have abandoned retrogressive practices such as child marriage (Sona Ram Bishnoi, personal interview, December 27, 2018) as they look forward to giving the children a professional education.

Attachment to ideals of not harming nature and life in any form still remains the hallmark of the community spirit. The recent awakening (since the past two decades), the need for understanding administrative, legal and judicial provisions and possibilities, is reflective of a replenished repository of environmental defence as per changing needs of the day (Mahipal Bishnoi, personal interview, December 28, 2017). Just as there are progressive scholars, intellectuals and leaders on the scene, with the arrival organisations such as the Bishoi Tiger Force (BTF), one reckons the presence of progressive environmental activism and legal experts on the Bishnoi social horizon.

Bishnois: The evolution of a nuanced conservation ethic

Conservation as a practical necessity: In the arid and semi-arid regions of western Rajasthan, Bishnoism as a sect has not only proposed, but over the ages, has also learnt to internalise a historical prudence in practising a conservation ethic in the Thar Desert. The social concern for the environment in medieval Rajasthan manifested itself in various forms. Most of the Bishnoi rules suggested maintenance of harmony with the environment, such as the prohibition on cutting green trees and animal slaughter. One plausible explanation is that the economy was primarily sustained by animal husbandry. Hence, any slaughter, even during droughts, would have reduced the means of livelihood.

Similarly, the cutting of green trees was prohibited, as it would reduce the availability of green fodder for the animals especially in this region where natural vegetation was very thin and sparse. Jambhoji’s teachings, which were congruent with the interests of the common people, became immensely popular primarily in the arid regions of Bikaner and Jodhpur. The number of his followers increased manifold in these areas. His sect became so influential that the rulers of these states were forced to respect his sermons. The Bishnois have since long campaigned for placing restrictions and punishments for cutting trees.

The founder of the Bishnoi sect was not alone in attempting to influence conduct towards living beings via religious and ethical transformation. However, Bishnois adopted certain practices en masse inspired by Jambheshwar (Kumar 2005:143). To inculcate respect and a spirit of sharing for all living creatures and frugality with the use of natural resources; not to burn fuel food for cooking but search patiently for cow dung each day (WildFilms, India 2012); store rain water; build granaries to preserve excess grains; filter water to avoid harming microorganisms; are some practices that the Bishnois adhere to. In this sense, their various modes and strategies of conservation are truly inspirational besides being timely (Dreamz 2011).

The Bishnoi attachment to their customary practices with regard to environment, conservation and religious ceremonies such as the daily havan (a ritual burning of offerings such as grains and ghee, which is held to mark births, marriages, and other devotional special occasions) continues with native enthusiasm (For more details, see Singh 1998:188-191). It is noteworthy that for the daily havan, Bishnois use coconut husk and not wood (Temple Priest Khejarli, personal interview, December 26, 2018). Also, a Bishnoi woman never cuts trees or shrubs for fuel or food (Ram Niwas Budhnagar, personal interview, December 28, 2018). Going one step beyond the 29 tenets, one of which states, ‘not to cut trees’, these women walk for hours along lakes and grazing areas to look for and collect dung (Poka Ram Bishnoi, personal interview, July 22, 2012).

Conservation as a daring ethic: The Bishnoi community was very attentive to environmental well-being in the areas surrounding their houses and fields (Kumar 2005:147). Individual incidents of martyrdom in the protection of wildlife have been reported in 1603 and 1643 AD. However, it was the massacre at Khejarli that displayed for the first time how seriously the Bishnois can take this adherence to the 29 rules of their sect.

Khejarli or Khejadli is a village in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, India, 26 km southeast of the city of Jodhpur. The name of the town is derived from khejri trees, which were in abundance in the village. In the year 1730 AD (Vardhan 2014), the king of Jodhpur sent his army out to cut trees to build his palace. When his army started to log a Bishnoi forest, they staged a non-violent protest, offering their bodies as shields for the trees. The soldiers had warned that anyone intending to stay in their way would share the fate of Amrita (or Imarta/Imarti as she is often also referred to by the locals) and her three daughters who had taken the unique step of hugging trees following their mother’s action, and had been killed. Men, women and children from 83 different villages stepped forward, embraced the trees and let themselves be axed to death one after the other.

The army’s axes had already killed 363 people, when the king, Maharaja Abhay Singh, hearing of their courage, halted the logging and declared the Khejarli region a preserve, and off limits for logging and hunting. He issued a royal decree engraved on a tambra patra (a letter engraved on a copper plate) prohibiting the felling of trees in the Bishnoi areas. The Bishnois as well as non-Bishnois refer to the tambra-patra declaration as a victory of people’s efforts at conservation.

Till today, the Bishnoi community commemorates this collective sacrifice and the symbolic victory in Khejarli by maintaining the place as a heritage site. An annual fair is organised at the location near Jodhpur, which also maintains a functional temple. In 1988, the Government of India commemorated the massacre formally, by naming the Khejarli village as the first National Environmental Memorial (Clarke 1991). A cenotaph now stands at the site as a memorial to the Bishnoi lives lost at the massacre site, which is collectively maintained through community funding and at times by private donations.

Incidentally, the last words uttered by Imarta Devi (also known in local parlance as ‘Ma Amrata Devi’), the first woman who died in defence of the khejri trees during the 1730 Khejarli massacre, as explained by the priest at the Khejarli Temple (personal interview, December 27, 2017), are as follows: Sar sāntey rūkh rahe to bhī sasto jān (even if one were to get their head severed to save a tree, still it is a cheap bargain). The massacre and martyrdom in Khejarli is therefore read as the willingness of the Bishnois to sacrifice life for the sake of protecting nature (Lal 2003; Fisher 1997; Gadgil 1999; Sankhala and Jackson 1985). While it continues to colour the narratives of Bishnois and foster ecological memories, the Khejarli massacre, its innovative protest that entailed tree-hugging, is often said to be the ‘first Chipko’ movement and also an inspiration for the one that was organised later, in 1972.

Conservation as a metaphor and symbol: A holy site of the Bishnois is known as a dham. Dhams are reflective of the sect’s organisational principles and religious philosophies. Stories and anecdotes as well as natural relics associated with these religious sites are replete with imagery and allegories of the Bishnoi life-world.

The most prominent of the Bishnoi dhams (holy places of pilgrimage) is situated in a village called Mukam in a temple in Nokha Tehsil of the Bikaner district of Rajasthan. Other equally important ones are called Pipasar, Samrathal Dhora (situated 3 km from Mukam), Jangaloo, Rotu, Lalasar, Jambolav and Lodi Pur. Lohawat, Ramdavas, Bhur Tiba and Prachin Vishnoi Mandir Kanth (in District Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India), Sameliya, and Kuka (Bhinmal) are the remaining holy places of significance.

Significantly, each dham carries its own tale of conservation and is linked to significant events relating to Jambheshwar’s life as associated with nature. These range from the plantation of trees or their revitalisation, maintenance of sacred groves and creation of ponds, judicious use of water or setting aside feeding areas and shelters for birds and animals alike. The area-specific stories and traditions continue to be taken care of by the community.

Other ritualistic practices observed and performed in all the dhams inspire the circulation of ecological traditions. In addition, the holding of fairs and large-scale commemorative havans help nurture the Bishnoi conservational ethic in successive generations. At the same time, some newer trends have also sprung up from the thresholds of the community in the form of organised protest movements in defence of the environment. BTF is one such organisation that is working voluntarily for saving wildlife from damage and chasing the processes of justice in cases of local environmental crimes (see allied article and interview. Videos on the BTF included in this module).

Notes

[i] Orans (sacred groves) are small patches of vegetation in the villages of Rajasthan which are traditionally protected and managed by the local people. However, orans are areas that are, ideally speaking ‘undeveloped’ by humans: open spaces for nonhuman animals alone, where there are no buildings or agricultural activities. They also include natural or man-made ponds that are dug and maintained by community members to provide water for the village and the wild animals in the area. Studies show that Bishonis manage the upkeep of sacred groves very well in their villages. The Bishnnoi Orans, some of which are confirmed to be two to four hundred years old, have a collective grain bank. Each Bishnoi family contributes one tenth of the grains from their yearly crop. These gains are used for feeding wild birds and animals. Generally, a big bowl of grains (bajra i.e.miilet) and a water trough are kept in a corner place of orans. They believe that the animals are born along with the human beings on the earth, therefore, they (animals) also have the right to share their food and water along with the human beings (see Reichert, 2015: p77).

[ii] see Jain 2010, for debates on mixed, transitory origin of Bishnois.

[iii] A notable contribution of the Sufis was their service to the poorer and downtrodden sections of society. They were against formal worship, rigidity and fanaticism in religion, (Anniemarie, 1975; Abidi, 1992; Raziuddin, 2007; and Alvi, 2012). On the other hand, Bhakti movement was a socio-religious movement that opposed religious bigotry and social rigidities. The Bhakti saints infused a new sense of confidence among the discriminated sections of society and their call to social equality attracted many a downtrodden (Kieckhefer and Bond 1990; Nelson 2007; Government of India, 2011 Pechelis 2014; and Hawley 2015).

[iv] Bishnoi, is the literal word that stands for number 29, i.e. Bish implies, 20 and noi means 9 in terms of numerical values- as expressed in the local dialect.

[v] Another such philosophy that flourished around the same time was that of Jainism which is inherently against killing of any living beings. Bishnois known to have evolved through an amalgam both Hinduism and Islam, yet not completely given in to either, now, are evidently and completely within the Hindu fold. Aside from the fact that Bishnois’ recognise themselves as an Hindu sect, Guru Jambheshwar, the founder himself was a Hindu, (Khan 2004 and Maheswari 2011). So while cherishing its mixed origins and innovative environmental responsibilities, the community holds itself as a Hindu sect.

[vi] These were collected and compiled by Vilhoji, one of Jamabaji’s follower, who live during 1532-1616.

[vii] Though Bishnoism has not been expanding in terms of new membership, the Bishnoi respondents consulted for this research, interestingly co-incide with their opinion, that anybody who agrees to abide by Jambhoji’s code of 29 principles, would be welcomed by the Bishnois as a part of their community.

[viii] This comes across in my interviews and conversations with Bishnoi actors during my recent field in December 2018. When asked how much influence caste assumes in their life, they are quick to insist how their point of origin as sect was an evolutionary (meaning thereby that no political rebellions were staged, so to say) protest against discriminatory social conditions, out of which caste system was an important one.

[ix] Jambhoji’s teachings are clearly anti-caste; he explains that one does not become pure by birth or caste, but by one’s actions. In his 26th shabad, he states that “…just by getting birth in high-class family, one does not become superior; superiority comes by practicing fine qualities.” Like many other saints and gurus of the Bhakti movement, he accepted people from any creed and rejected the caste system (Reichert 2015).

[x] The Indian caste system, according to Rakesh Bhatt, has had no influence on the philosophical underpinnings of the Bishnois.

[xi] For more details, see Maheswari 1970; Singh 1998; Singh and Saxena 1998; Singh 2013; Soule 2003.

References

Abidi, S.A.H. 1992. Sufism in India. New Delhi: Vishwa Prakashan.

Alvi, Sajida Sultana. 2012. Perspectives on Mughal India: Rulers, Historians, Ulama, and Sufis. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Anizinam, C. 1995. ‘Ecology and Ethnomedicine: Exploring links between current environmental crisis and indigenous medicinal practice.’ Social Science Medicine, 40(3): 321-329.

Bhatt, Rakesh. 2015. ‘Bishnois: The Ecological Stewards’. Online at http://www.ymparistojakehitys.fi/susopapers/Background_Paper_10_Rakesh_Bhatt.pdf. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

Bishnoi, Vandana, and N.R. Bishnoi. 2000. ‘Bishnoism: An Eco-friendly Religion.’ Religion and Environment. Edited by Krishna Ram Bishnoi and Narsi Ram Bishnoi. New Delhi: Commonwealth Publishers.

Blunt, E.A.H. 2010. The Caste System of Northern India. Delhi: Isha Books.

Chapple, C. K. 2011. ‘Religious Environmentalism: Thomas Berry, the Bishnoi, and Satish Kumar.’ Dialog: A Journal of Theology Communication Theory 50(4).

Chandla, M.S. 1998. Jamboji: Messiah of the Thar Desert. Chandigarh: Aurva Publications.

Clarke, Robin. 1991. ‘Traditional Solutions.’ In Water: The International Crisis. London: Earthscan.

Crooke, W. 1896. The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western India. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dalal, R. (2014). Hinduism. An Alphabetical guide. New Delhi: Penguin.

Dainik Bhaskar. 2011. ‘Salman ko dikhayi lal batti aur kale jhande’ (Salman Shown red light, black flags). Dainik Bhaskar, Jaipur, January 24.

Deb, Debal. 2012. Beyond Developmentality: Constructing Freedom and Sustainability. London: Routledge.

Devi, Pranashree. 2012. ‘Bishnoi Community: The Ecologist.’ Online at http://www.traveldiaryparnashree.com/2012/10/bishnoi-community-ecologist.html. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

Fisher, R. J. 1997. If Rain Doesn’t Come: An Anthropological Study of Drought and Human Ecology in Western Rajasthan. New Delhi: Manohar. Gadgil, Madhav. 1999. ‘The Indian Heritage of a Conservation Ethic’. In Ethical Perspectives on Environmental Issues in India. Edited by George A. James. New Delhi: A. P. H. Publishing Corporation.

Jain, Moti Lal. 1975. The Rajasthan tenancy act, 1955. Ajmer: Kanoon Saptahik Publications. Jani, Pankaj, 2010. Bishnoi: An Eco-Theological, ‘New Religious Movement’, in the Indian Desert. Journal of Vaishnav Studies 19.1.

Jain, Pankaj. 2011. Dharma and Ecology of Hindu Communities: Sustenance and Sustainability (New Critical Thinking in Religion, Theology and Biblical Studies Series). Farnham: Ashgate.

Khan, Dominique-Sila. 2003. Conversions and Shifting Identities: Ramdev Pir and the Ismailis in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors.

Khanwalkar, Sandeep. ‘Rajasthan: Tales of co-existence.’ Online at http://www.kalpavriksh.org/images/CCA/Directory/Rajasthan_StateChapter.pdf. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

Kumar, Mayank. 2005. ‘Claims on Natural Resources: Exploring the Role of Political Power in Pre-Colonial Rajasthan, India.’ Conservation and Society 3 (1): 134-149.

Lal, V. 2005. ‘Bishnoi’. In Encyclopaedia on Religion and Nature. Edited by Bron Taylor. London: Continuum.

Lorenzen, David. Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. New York: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Mukhopadhyay, Durgadas. 2008. ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Water Resource Management’. In The Future of Drylands: International Scientific Conference on Desertification and Drylands Research, Tunis, Tunisia, 19-21 June 2006, edited by Catthy Lee and Thomas Schaaff, 165. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Maheshwari, Heera Lal. 1970. Jambhoji, Bishnoi Sampradaya aur Sahitya Part I: Jaipur: Rajasthan University.

———. 2011. Shabadvani. Jaipur: Granthghar.

Menon, G. 2012. ‘The Land of The Bishnois—Where Conservation Of Wildlife Is A Religion!’ Online at http://www.thebetterindia.com/5621/the-land-of-the-bishnois-where-conservation-of-wildlife-is-a-religion/. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

Munhta Nainsi. 1962. Munhta Nainsi ri Khyat, volume II. Edited by Badri Prasad Sakariya. Jodhpur: Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute.

Nelson, L. 2007. An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. Pennsylvania: Liturgical Press.

Pechelis, Karen. 2014. The Embodiment of Bhakti. London: Oxford University PressRaziuddin, Aquil. 2007. Sufism, Culture, and Politics: Afghans and Islam in Medieval North India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Reichert, A. 2013. ‘Bishnoism: An Eco Dharma of the People Who Are Ready to Sacrifice their Lives to Save Trees and Wild Animals.’ Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 3: 19-31.

———. 2015. ‘Sacred Trees, Sacred Deer, Sacred Duty to Protect: Exploring Relationships between Humans and Nonhumans in the Bishnoi Community. MA Thesis, Department of Classics and Religious Studies, University of Ottawa.

Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 1891. ‘Database: General report on the Census of India 1891.’ Census of India.

———. 2011. ‘Tables on Individual Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST).’ Census of India.

———. 2011. ‘Census India SRS Bulletins.’ Census of India.

———. 2013. ‘Census India SRS Bulletins.’ Census of India.

Sankhala, K. S., and Peter Jackson. 1985. ‘People, Trees and Antelopes in the Indian Desert.’ In Culture and Conservation: The Human Dimension in Environmental Planning, edited by Jeffrey A. McNeely and David Pitt. London: Croom Helm.

Schimmel, Anniemarie. 1975. Sufism in Indo-Pakistan. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Singh, Katar. 1986. Introduction to Rural Development Principles, Policies and Management. London: Sage Publication.

Singh, K.S. 1998. Foreword to Rajasthan. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

Singh, M.H. 2013. The Castes of Marwar. Census Report 1891. Introduction, Komal Kothari. See section on Bhils (pp.55-58); Section on Ban Bawaris (pp.60-66). Jodhpur. India: Bharat Printers.

Singh, G.S. and K.G. Saxena. 1998. ‘Sacred Groves in the Rural Landscape, A case study of the Shekhala Village in Rajasthan.’ In Conserving the Sacred, for Bio-Diversity Management. New Hampshire: Science Publishers.

Siva Ram, P. ‘Community Initiatives In Environment Management—A Case Study Of Bishnois In Jodhpur District.’ Online at http://www.panchayatgyan.gov.in/documents/30336/0/4.+Article.+Bishnois.pdf/af465a78-dab9-403f-a2f7-4949644848b8. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Soule, J.P. 2003. ‘The Desert Dwellers of Rajasthan: Bishnoi and Bhil People.’ Online at http://www.nativeplanet.org/indigenous/cultures/india/bishnoi/bishnoi5.shtml. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Tobias, M. 1988. ‘Desert Survival by the Book.’ New Scientist 1643: 29-31.

Turner, V. 1967. ‘The Liminal Period in `Rites de Passage.’ In The Forest of Symbols. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Vardhan, H. Bishnoi. ‘Sacrifice for Conservation, in Bishnoi Samachar.2014: Online at http://jambhguru.blogspot.ch/2014/07/sacrifice-for-conservation.html. Retrieved December 29, 2018. Also see www.birdfair.org.