The Karaga festival or Karaga jatre (a periodic festival in honour of a deity) is celebrated annually in the Chaitra (March/April) month of the Hindu calendar in the south Indian state of Karnataka, mainly by the Tigala community; though, today it is attended by people from all sects. The Tigalas consider themselves descendants of the epic heroine Draupadi, and are traditionally urban gardeners, horticulturists and lake settlers. There are three main sub-groups within the Tigalas—Vahnikula Kshatriyas (Tamil speaking people belonging to the lineage of Vanniyars or Vanniyans), Shambukula Kshatriyas (Tamil speaking descendants of the sage Shambu who is said to have migrated from the neighbouring states) and Agnikula Kshatriyas (Kannada speaking descendants of the folk hero Agni Banniraya, native to Karnataka).

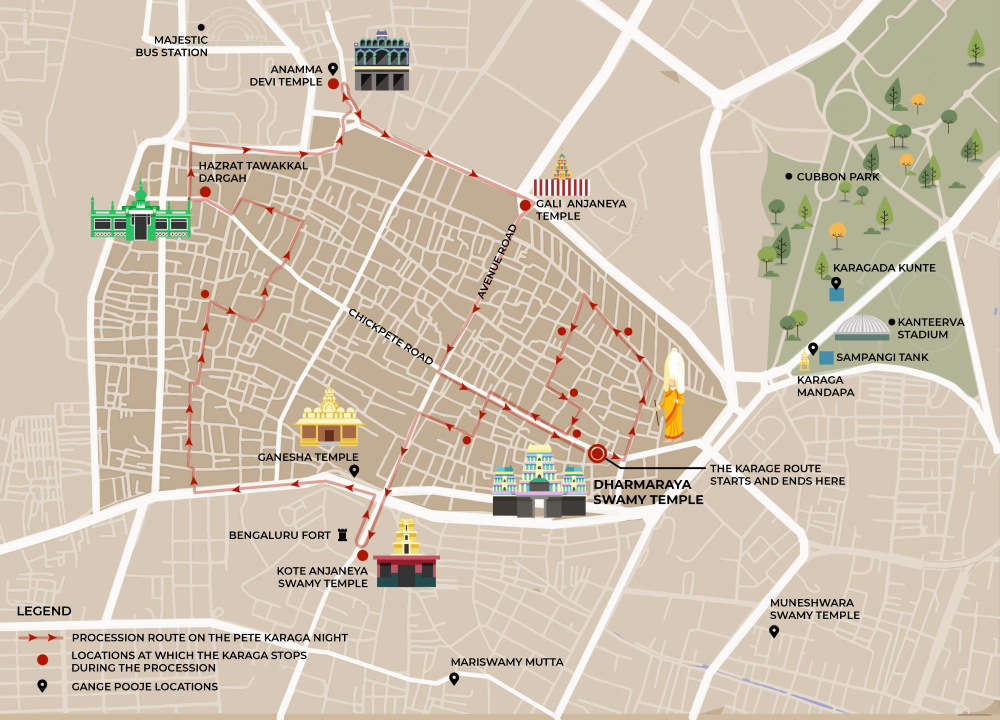

The Vahnikulas follow the lunar calendar, hence their Karaga festivities take place after moonrise and before sunrise while the Shambukulas and Agnikulas follow the solar calendar and their festivals are celebrated during daytime.[1] One of the four temples in the city dedicated to Draupadi and Pandavas, the Dharmaraya Swamy temple (locally known as Dodda Dharmaraja devastana) in Tigalarapete is the principal ritual centre of the Karaga festival. The other three temples—Chikka Dharmaraja temple and Dharmaraja and Panchali temple at Kalasipalya, and Ekambareshwara Dharmaraja temple at Shivajinagar[2]—also have Karaga festivals in honour of the presiding deities, but the Pete (old/market town) Karaga, also known as Bengaluru Karaga, is considered the primary civic ritual of the city. The Dharmaraya Swamy temple is believed to have been built between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but Karaga seems to have been celebrated since much before.

The various dynastic rules and historical episodes that Benguluru as a region has seen have played a significant role in shaping the Karaga festival as celebrated within its parameters. An inland city, Bengaluru is strategically located in the geographical centre of the southern peninsula surrounded by hills and valleys, equidistant from the eastern and western coasts. (Fig 1) Due to its natural defence fortification, many kingdoms like the Gangas, Cholas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagara emperors, Marathas, Wodeyars of Mysore and even the British ruled over the city and its environs. The rulers patronised the Karaga festival by making donations for its celebration, the maintenance of the temple, and initiated one of the earliest documentations of the festival—during the period of the Wodeyars in 1811. During the rule of Kempe Gowda I of the Vijayanagar kingdom in the sixteenth century, Karaga festival gained more prominence with the influx of Tigalas from the neighbouring states, and again in the eighteenth century, under Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan, a large number of Tigalas migrated to Karnataka for better economic opportunities.

Folk Origin of the Festival

The basic folklore associated with the origin of Karaga festival is derived from Mahabharata and has numerous variations. The most common legend is around the demon Timarasura. The Pandavas, Krishna and Draupadi were on their way to heaven after completing their exile in the forest when Timarasura called out to Draupadi and teased her. Since her husbands and Krishna were ahead of her, she was left alone to fight the demon. Timarasura was armed with a boon from Lord Shiva that even from a single droplet of his blood that fell in a battle, would arise thousands of Timarasuras. Draupadi assumed her primeval form of Adi Shakti, and when she shook the cloth covering her breast, warriors like Durga pujari, gante pujari (bell priest), ganachari (community chieftain) and veerakumaras (hero protectors of the Goddess) sprang from it. The battle was terrible and long; as the Goddess struck the asura, his blood flowed and more asuras emerged. Eventually, the Goddess struck one final blow and licked clean the flowing blood and swallowed the demon. The Goddess then regained her original form of Draupadi and promised to visit her warrior sons once every year.

There is another tale that describes a scene after the completion of the Kurukshetra war when Dharmaraja Yudhishthira and Draupadi were crowned the king and queen. The couple witnessed a young woman riding a horse while her husband was walking with her slippers on his head and his mother limping across the road. This was a sign of the onset of the Kaliyuga (last of the four ages) and signalled that it was time for Draupadi and Yudhishthira to make a departure to heaven. On their way to heaven, Draupadi was confronted by kalipurusha (human form of Kaliyuga); the Pandavas, who had received news of Krishna’s death, were in no state to help her. Draupadi prayed to Lord Shiva and Parvati, who gifted her their powers; she was also advised to make a pot and safeguard her shakti (power) in it and then warriors were born for its protection.[3]

These two narratives about the origin of the festival indicate that the Karaga festival depicts the victory of good over evil through the defeat of the asura at the hands of the Goddess, who appears as a guardian of the sociocosmic order, and commemorates the birth of the female principle of divinity, Shakti.

A Celebration of Nature and Water

The word karaga means an earthen pot made from unbaked clay. The pot plays a crucial role in the festival and is sacred as it is supposed to embody the Goddess's power which is attributed to the priest when he is carrying the pot. Spread over 11 days, Bengaluru Karaga essentially celebrates nature and water as is evident from the Gange puje ritual (worship of Goddess Ganga)[4] and incorporates features of Bengaluru’s waterbodies with the religious landscape of the old city. Karaga festival also involves worship of local boundary goddesses (protector goddesses found on the edge of a territory) like Annamma, Mariamma, Patalamma, Muthyalamma, Yellamma and Gadagamma (goddesses summoned to cure various forms of poxes), all of whom appear as Draupadi’s sibling in various folk stories. Another special element of the jatre is its association with Hazrat Tawakkal Mastan Baba, an eighteenth-century Sufi saint, who was a popular Islamic figure in the region. The coming together of the Tigala sect and the hero songs of Draupadi through the festival rituals, local goddess worship, honouring of water and nature through traditions, a Sufi connection and episodes from the Mahabharata, make Karaga festival unique to the region. As the Tigalas, gardeners by profession and believed to be born from fire, are at the forefront of Karaga, the festival symbolically celebrates Bengaluru as a ‘gardener’s city’ as well as ‘city of children of the fire’.[5]

Key Players of the Festival

A festival of the scale and fervour of Karaga involves numerous ritual participants of which the Karaga priest (who bears the karaga) and veerakumaras, who are identified by their katti (sword), are the most important ones (Fig 2). The priest is chosen six months prior to the festival, during which he is on a strict diet and goes through training at garadi manes (ancient gymnasiums). For the 11 days of the festival, the priest breaks off all contact with his family, and lives a life of solitude and penance at the Dharmaraya Swamy temple. It is believed that the strict routine enables him to bring in the Goddess’s strength into him and manifest male and female characteristics in himself, which prepares him to receive the Goddess’s energy on the day of her birth. It is also customary for his wife to get rid of all symbols of her marriage to the priest for the period.

Other crucial members of the festival include kula gowda (community headman), who is responsible for all the preparations of the festival; ganachari, who oversees all the religious matters of the community; gante pujari, who decorates the shrine on all days of the performance, sings invocation songs along with bells at different temples and tanks, and is also the Karaga priest’s instructor; kula purohita (community priest), who performs various activities like marriage of Draupadi and Arjuna, induction of veerakumaras, and cleansing rituals; Potharaja pujari (priest from the Potharaja household, a local king who is believed to have ruled the region when the Pandavas visited the city), whose chief role is to ensure that all festivities are carried out without any obstacles; bankadasi (banka player), who plays the banka (bugle like instrument) to call upon the spirits; and lastly, kolkar, who carries the news of the rituals.[6]

Rituals and Festivities

The first day of the festivities is initiated by the hoisting of flag on sapthami (seventh day) of the Chaitra month. The yellow coloured dharma dwaja (flag of morality) is brought from the Potharaja household and is tied to a bamboo pole brought by Vahnikula Kshatriyas of Jaraganahalli forest. The bamboo is picked from Anjanapura, a suburb in the south of the city and is transported to Jarganahalli, where it is chopped at an auspicious moment early in the morning and is taken to the Dharmaraya Swamy temple by afternoon; on the same day, the kula gowda invites the ganachari, gante pujari, karaga pujari, and Potharaja pujari to participate in the festival. The kula purohita performs the cleansing puja of the temple premises before the start of the rituals. After the flag is hoisted at midnight, the other participants of the festival, like the veerakumaras and the temple menial workers, are initiated into their roles by tying a kankana (woollen threads wrapped around turmeric root) on their wrist. The veerakumaras perform their first swordplay chanting ‘Alia Lalla Lalla Di’, a magical formula supposed to pacify the Goddess.

During the five days between the second to the seventh day of the Karaga festival, the group of priests led by the Karaga priest visit temples (Figs 3 and 4), waterbodies, and three gardai manes in nine directions across the city to cleanse them to receive the Goddess. The temples dedicated to Shiva, Ganesha and Annamma Devi are visited on specific days while the Ellusutina Kote (seven-circled fort) temple is visited almost every day of the festival. The Karaga priest bathes in the waterbody at each of these locations and performs Gange puje.

Another significant ritual of the Karaga festival is the aarti deepotsava (festival of lights; Fig 5), performed on the evening of the sixth day when women of the community are summoned by priests to participate in the festival. The women welcome the priests to their houses two oil lamps on a plate and by washing their feet and performing puja to a trident carried by them. By midnight, all the women arrive at the Dharmaraya Swamy temple with elaborately decorated lamps containing sacred pots made from pounded jaggery and covered with jasmine and firecracker flowers. During aarti deepotsava, swordplay and stunts are performed outside the temple by children of the community. The main purpose of aarti deepotsava is to invite Goddess Adi Shakti into people’s houses to fulfil their promises or to pray to her to get a strong husband like Bhima.[8]

Hasi karaga (birth of the Karaga), performed on the night of the seventh day, is the most significant ritual of the Karaga festival. It is conducted after sundown at the Hasi Karaga mandapa with thousands of devotees gathered to witness the manifestation of the Goddess in the karaga. The Karaga priest and his troupe perform secret rites at the mandapa covered by a white cloth and protected by veerakumaras. At about midnight, the Goddess manifests herself in the karaga made from the raw sediments of the Sampangi lake, accompanied by frenzied trembling and dancing by the Karaga priest, loud noises from the drums played by musicians and hunting horns blown by the bankadasi, and by chants of ‘Govinda’ from the devotees. Finally, a priest who holds a dagger in his right hand, carries the karaga on his waist to the Dharmaraya Swamy temple.

The eighth day is for pongal seve (sweet rice offering); on the night of the eighth day, women prepare pongal with rice, milk and sugar inside the temple compound and place it in nine directions to appease the nine planets. The pongal cooking goes on alongside the narration in Tamil of the story of Draupadi in disguise as a gypsy during her exile in the forest.

The story goes: While travelling from the tenth forest to the eleventh one, Draupadi felt the urge to meet her relatives at the capital city of Hastinapur; she, along with Sahadeva went cloaked as gypsies, attending to Gandhari, mother of the Kauravas. However, Duryodhana grew suspicious of Draupadi’s identity and wanted to imprison her and Sahadeva. Arjuna came to Draupadi’s rescue in the guise of a nomad and warned Duryodhana, who then agreed to set them free in exchange for pongal that Draupadi had to prepare by cultivating rice. Duryodhana purposely gave her boiled grains which would not sprout, but Draupadi still managed to grow full length stalks of rice in a day with which she prepared pongal and then fled the city with Arjuna and Sahadeva.[9]

The karaga procession on the night of the ninth day is the most attended event of the festival. The karaga that night is decked up with jasmine flowers and representative symbols of the Goddess like the conch, discus, trident, mace, and drum adorn it. The Karaga priest is dressed in a turmeric yellow sari with a red border, bangles, necklaces and a gold waistband. (Fig 6) Once the karaga is mounted on his head, the priest starts the night procession from the Dharmaraya Swamy temple and visits the other temples in the pete and the dargah (Fig 7), and having touched the edges of the old city, returns to the temple in the early hours of the next morning. The common story about the relationship between the Goddess, temple and the dargah is that once at the time of a Karaga festival, the Sufi saint was hurt during the procession and he cursed the karaga such that it could not move forward until turmeric from the temple was applied to his wound to pacify him, since then, the karaga visits the dargah to commemorate this event.[10]

After the procession, the karaga is placed in the sanctum of the temple and the group of priests proceed to the Ellusutina Kote temple with a chariot carrying the idols of Arjuna, Draupadi, and Potharaja. At the temple, the gante pujari recites Karaga Purana which describes the origin of the Vahnikula Kshatriyas, the history of Potharaja and his relationship with the Pandavas and Draupadi, and the performance of the goat sacrifice. The songs are sung in Tamil and the prose is narrated in Telugu. After the completion of the anecdote, a goat is offered to Potharaja as a part of a promise made to him by the Pandavas in the courtyard of Dharmaraya Swamy temple.

According to popular belief, Potharaja, who was ruling over the region of Elaipur (present day Bengaluru), had imprisoned Bhima for causing the collapse of a fort wall of the city. Potharaja was a staunch Shiva devotee and had planned on sacrificing Bhima to gain the god’s favours. Lord Krishna and Arjuna, disguised as a nomad woman, came to Bhima’s rescue; Potharaja was mesmerised by the beauty of Arjuna in female form and wanted to marry him, but Krishna agreed for their alliance on two conditions: one that he will release all his prisoners and second that he would have to consume raw meat. As a part of the conditions laid down by Krishna, Potharaja consumed meat and by doing so, he dishonoured Lord Shiva as a true Shiva devotee never consumes meat. Thus, Krishna ensured that Potharaja was no longer eligible to gain the Lord’s favour. Since Krishna had promised Potharaja an alliance, he kept his word by marrying him to Pandavas’s sister, Shankavalli who emerged from Krishna’s conch as the daughter of Pandu and Madri. To further reinforce this relationship, Dharmaraja Yudhishtir (the eldest of the Pandavas) was married to Potharaja’s sister, Nagalamudamma.[11]

On the last day of the Karaga festival, everyone from the Tigala community participates in vasantotsava (spring festival), an event where men are challenged to break coconuts tied from a wooden frame while turmeric water is splashed on them. The festivities come to an end with the lowering of the flag and once all the rituals are completed, the Karaga priest returns to his family where he is remarried to his wife.

The Karaga festival is an integral part of the intangible heritage of Bengaluru and highlights a significant historic layer of the city and its secular character, one that must not be forgotten in the wake of modernisation. It also indicates the adaptable nature of traditions and festivals which find ways to sustain themselves even if the physical fabric of a space is continuously evolving due to developmental pressures as in the case of Bengaluru.

Notes

[1] Srinivas, Landscapes of Urban Memory, 98–104.

[2] Ibid., 108–09.

[3] Ibid., 151–52.

[4] Kumar, ‘The untold story of Bengaluru’s Karaga.’

[5] Srinivas, Landscapes of Urban Memory, 23–33.

[6] Ibid., 210–11.

[7] Ibid., 159.

[8] Ibid., 162.

[9] Ibid., 171.

[10] Ibid., 87.

[11] Ibid., 154–55.

Bibliography

Srinivas, Smriti. Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and the Civic in India’s High-Tech City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2001.

Kumar, Manasi Paresh. ‘The untold story of Bengaluru’s Karaga: A Festival that Worships Water.’ Citizens matter, Bengaluru, June 1, 2018. Accessed June 16, 2019. https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/karaga-worships-water-in-a-city-that-is-running-out-of-it-23993.