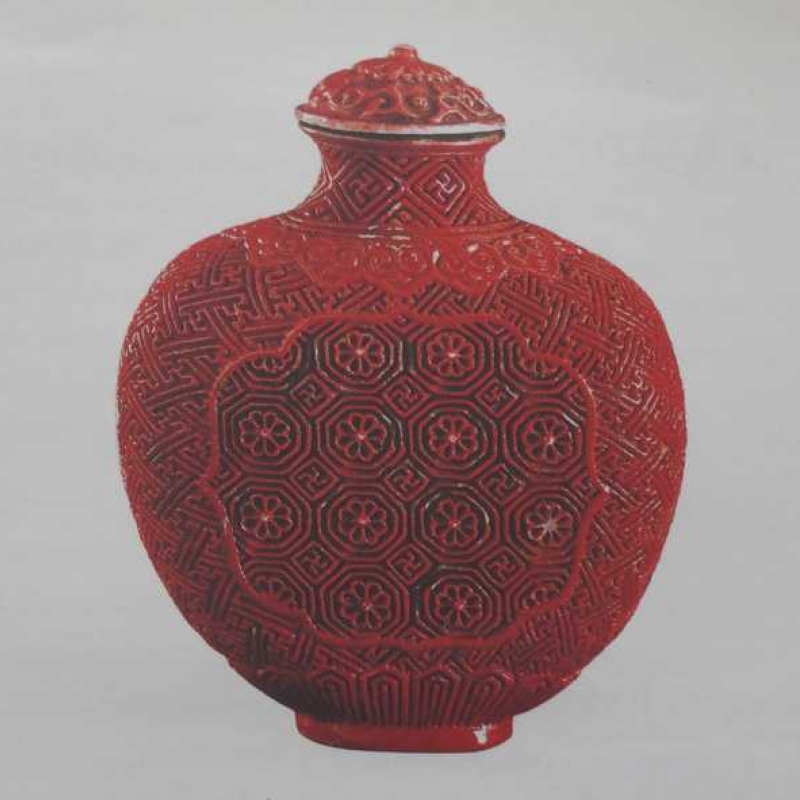

If there was one family that ‘knew’ Chinese art, and collected it with passion, it was that of the Tatas of Bombay. Politics aside, objects from the neighbouring country were a matter of pride in India a century ago, writes Prof B.N. Goswamy. (In pic: Snuff bottle imitating carved lacquer, porcelain with iron-red enamel, Jiaqing period, China, ca 1800; Photo courtesy: Sir Ratan Tata Collection, Mumbai/The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, under the title ‘Collector’s item, Made in China’ and is reproduced here with permission.

I have neither the competence, nor the intention, to write on the complex subject of India-China relations here. Nor do I wish to write—at least at this moment—on how the Indian market is becoming flooded with cheap icons of Indian gods and goddesses: ‘Made in China’ but routinely picked up by unsuspecting devotees. My intent is essentially to speak of how objects of Chinese origin used to attract collectors of art in India a century or so ago, mostly in imitation of the fashion for ‘chinoiserie’ that had seized Europe in the eighteenth century. At the turn of the twentieth century, or a little before that—it has been recorded—you would enter an affluent Indian house, say in Bombay or Calcutta, especially one that had any connection with the outside world, and not fail to notice Chinese objects scattered all over the drawing room: painted folded screens, vases and tea services, chairs upholstered in Chinese silk and tables with intricately carved legs, little porcelain figures of ardent lovers. To the outsider, these objects spoke of the owner’s wealth—for they were collected at considerable expense—and of his refined, at the very least eclectic, taste.

Not everyone collected Chinese objects with an equally discerning eye, however. Tawdry, ‘bazaar type’ objects abounded. But if there was one family that ‘knew’ Chinese art, and collected it with passion, it was that of the Tatas of Bombay. Two names from that distinguished family stand out: those of Sir Dorab J. Tata, and his younger brother, Sir Ratan Tata, both sons of the legendary Jamshedji Tata. Between them they owned an enormous number of art objects, as many as a thousand of them and a little more, now, having been gifted, forming a part of the collection of Mumbai’s premier museum: the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, formerly and for long years known as the Prince of Wales Museum. The bulk of the collection is made up, as Terese Bartholomew noted in her 2002 catalogue, of “Chinese porcelain, followed by jades, lacquer, cloisonné, wood carvings, bronze images, and snuff bottles”. Whether or not the great Five Blessings most valued in Chinese culture—longevity, health, wealth, love of virtue, and peaceful death—are hinted at but hidden in each object is not what every viewer could be looking for in this collection. But the sheer quality of some of these would shine through for everyone, even at first sight.

Also read | Art N Soul: The ‘Timeless’ Indian Shawl

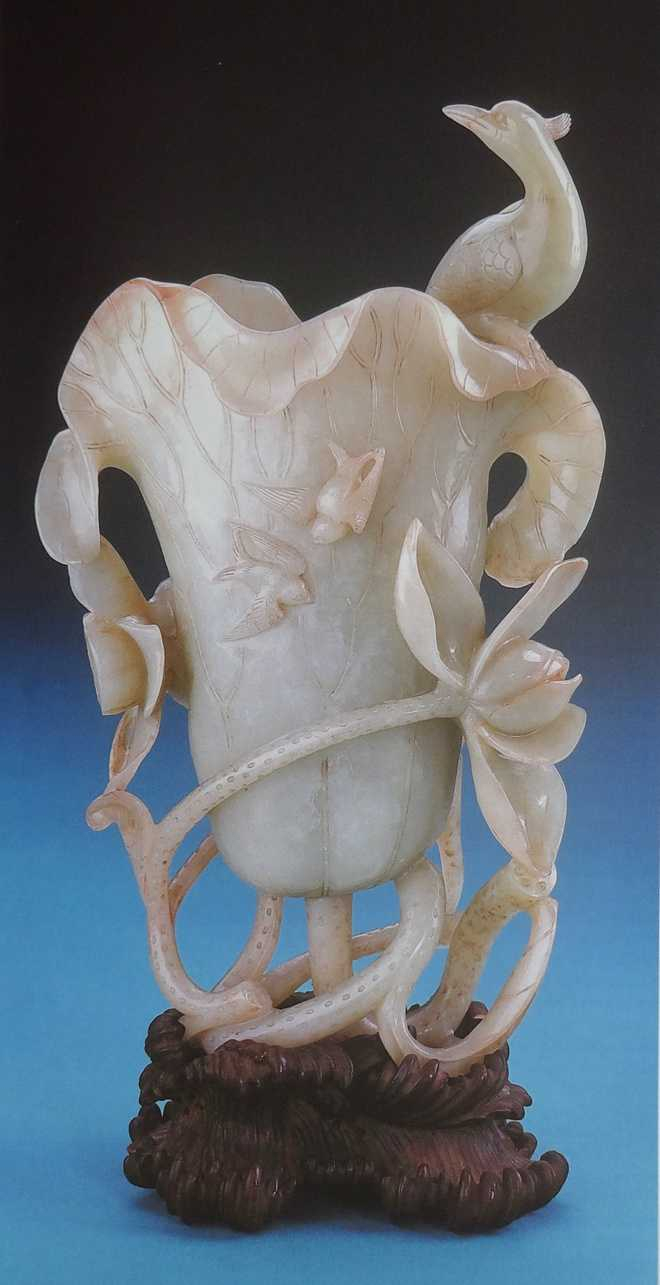

Consider, for instance, the ‘Container’, made of greyish nephrite from the Qing dynasty. Resting on a hardwood base, this exquisite object rises like a lotus plant emerging from fresh water with buds and sturdy undulating stems hugging its form. An egret, reminding one again of waterside surroundings, perches on the edge of the lotus leaf, and a pair of little swallows — essentially decorative in intent — carved out of the same piece of nephrite, adorn its side. There is an air of purity about the piece which comes across even if one does not know that there is a visual pun that is at play here, continuous harmony being hinted at in the form of the lotus. What function could this piece have been intended for — whether to serve as a flower vase or as an object for a scholar’s desk — becomes a truly redundant question, considering the sheer aesthetic pleasure that regarding it with care and patience can yield.

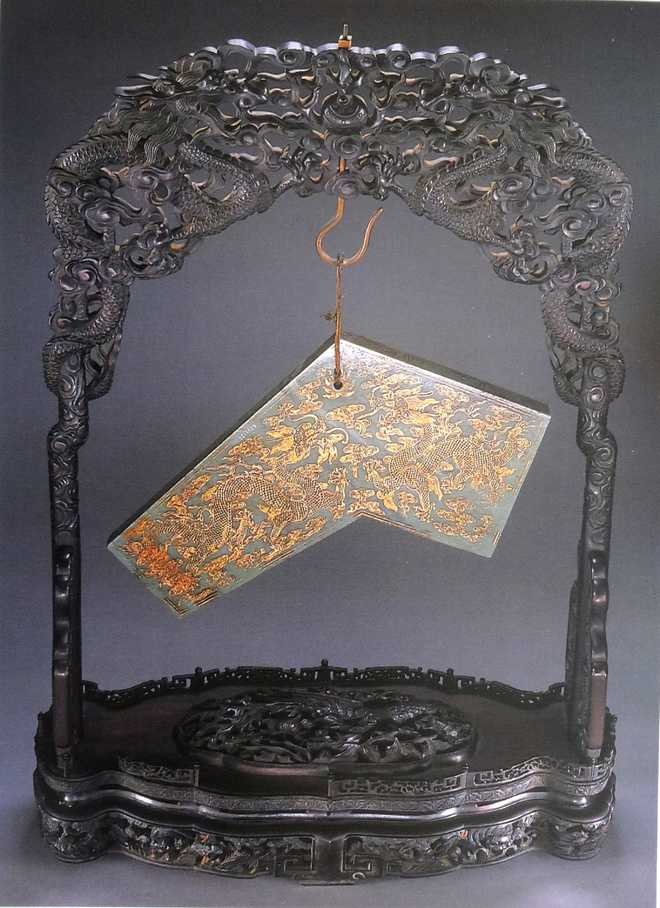

The remarkably complex, and superbly detailed, ‘Imperial jade chime’, another of the objects from the Tata collection, stems also from the Qing dynasty, but it bears a clear date: 1764 CE. Since one is not used to seeing objects like this, one needs to make a slight effort to comprehend what it is. It is in essence a ‘lithophone’, the hanging jade piece producing a measured sound (called taicou), the seventh in a scale, when struck with a wooden beater. But it could not have been produced as an isolated piece: it must, like other chimes, have belonged to a set of 16 ‘Imperial’ stone chimes, which were a part of a court ritual in the Qing dynasty. The delicate patterns in gold on the hanging piece, set off by the dark wooden ‘frame’, feature ‘two imperial five-clawed dragons contending for the flaming pearl among clouds’, as the catalogue says. Seeing it, one can lose oneself in the sheer refinement of detail.

Much smaller in size, for functionally it was meant to be so, is a snuff bottle made of porcelain covered with red enamel. Snuff bottles — little objects, meant to be carried on one’s body — stemmed originally from simple medicinal bottles, but had evolved into delicate works of art over time, and the Chinese, much addicted to inhaling snuff, loved showing their little ‘treasures’ off while using them in public. Whether or not snuff cleared the sinuses, or relieved headaches, the bottles yielded much visual delight, and one knows how incredible the variety of them was, made as they were of metal, wood, coral, agate and, of course, porcelain. This little object has a lid bearing chrysanthemum blossom and begonias with tendrils from which one descends to the main body which contains rosettes intervened by swastika motifs: a motif of Indian origin, incidentally, which a Tang empress of the seventh century had declared as the source of all auspiciousness.

Also read | The Kutch Museum

In contrast to these precious objects — contrasts are always useful — there stands a ‘reverse’ painting on glass showing, possibly, a courtesan: a ‘bazaar painting’ done for an Indian patron by a Chinese artist working in nineteenth century Kutch. But then that is not from the Tata collection.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.