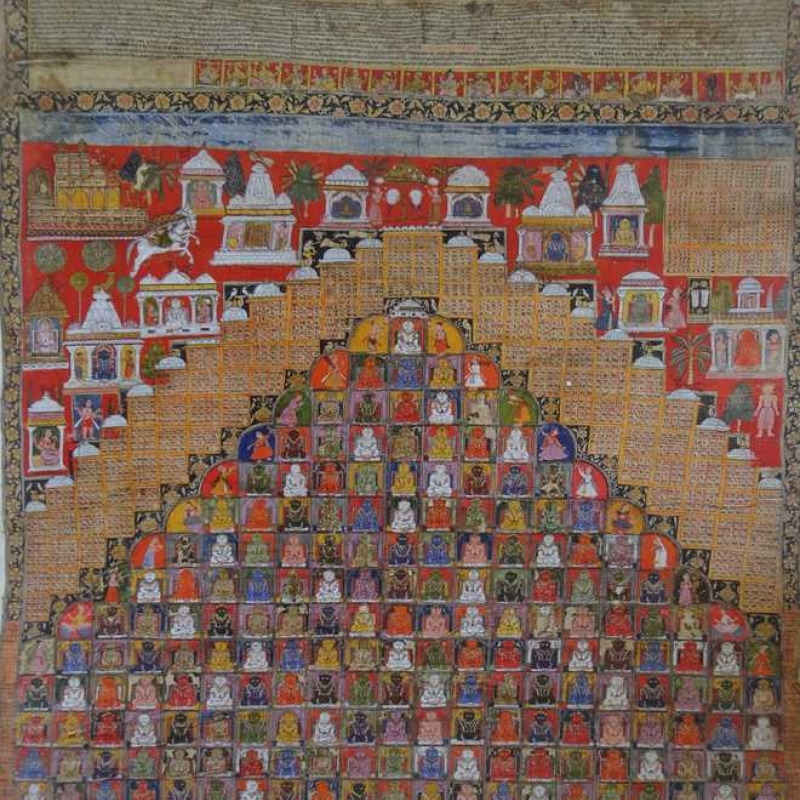

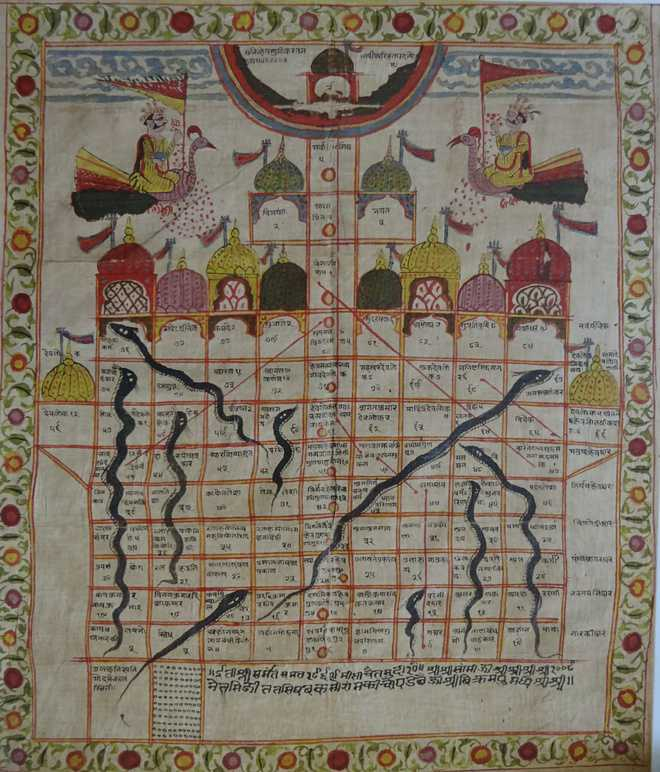

Kasturbhai Lalbhai Museum in Gujarat has a varied collection of Jain artefacts and symbolisms of worship. Prof. B.N. Goswamy writes about how the museum offers a rare peak into the Jaina world of retreat and meditation. (In pic: Detail from a Tirtha pata, Gujarat, 1641 AD; Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

Namo Arihantanam — I bow in reverence to Arihants

Namo Siddhanam — I bow in reverence to Siddhas

Namo Ayariyanam — I bow in reverence to Acharyas

Namo Uvajjhayanam — I bow in reverence to Upadhyayas

Namo Loye Savva Sahunam — I bow in reverence to all SadhusEso Panch Namoyaro — This five-fold salutation/Savva Pavappanasano — destroys all sins/Mangalanam Cha Savvesim — and amongst all auspicious things/Padhamam Havai Mangalam — is the most auspicious one.

— The Namokar mantra that precedes Jain prayers

Not far from the famed Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad, there is now another fine institution: the Kasturbhai Lalbhai Museum. I had, of course, heard of it and of its fast growing reputation, but it was only a couple of months ago that I got the opportunity to visit it. To put it simply, I came away greatly impressed. Named after one of the most distinguished industrialists and institution-builders of the city, and located in the now beautifully restored, sprawling old mansion where he spent many years of his life, the Museum bears a singularly elegant, understated look: cool marble floors, tastefully displayed objects in uncluttered spaces, room after feelingly done up room. Things do not come at you unannounced; nothing is overbearing. The sense one gets is of a collection of objects and appointments that meant something special to the owner/founder. The focus of the collection may not be sharp, but there is a warmth that things exude. And that is a feeling one does not come away with too often.

Also read | Art N Soul: Unusual Retelling of the Epic of Ramayana

There are things from the past and the present: miniatures that come from all parts of the country and all schools, pichhwais and patachitras, sculptures recalling different epochs, paintings of the Bengal school, a sizeable part of their collections acquired from the Tagore family, modern and contemporary works in large numbers. Interestingly enough, however, there are not many Jaina objects here even though the family has had a very long and intimate connection with the faith and its temples and bhandars: but then those are for the most part in the city’s L.D. Institute of Indology, I gathered. The Museum does not yet have many publications of its own, but one that was kindly given to me by Jaishree Lalbhai—member of the distinguished family and Director of the Museum—dwells exclusively upon Jaina themes. Jain Vastrapatas it is titled: produced in the same elegant vein that runs through the Museum, and filled with some exquisite objects. The word vastrapata denotes a large work painted on cloth, and that just about describes the category of objects included in the volume, even though a few works on paper are brought in too.

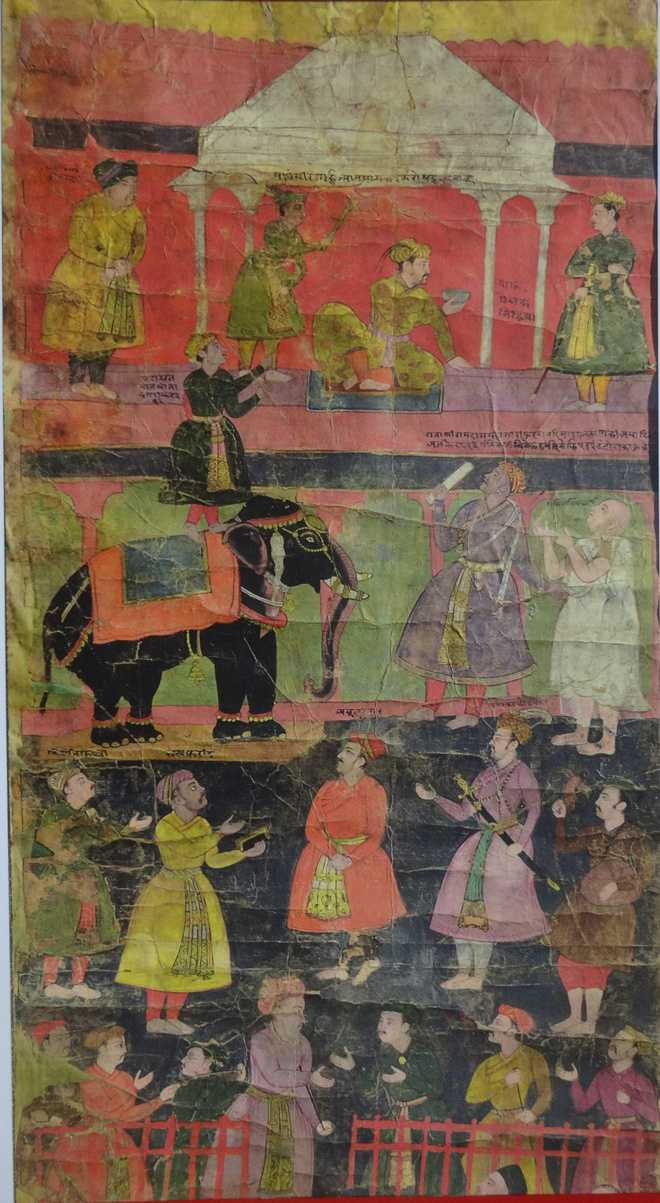

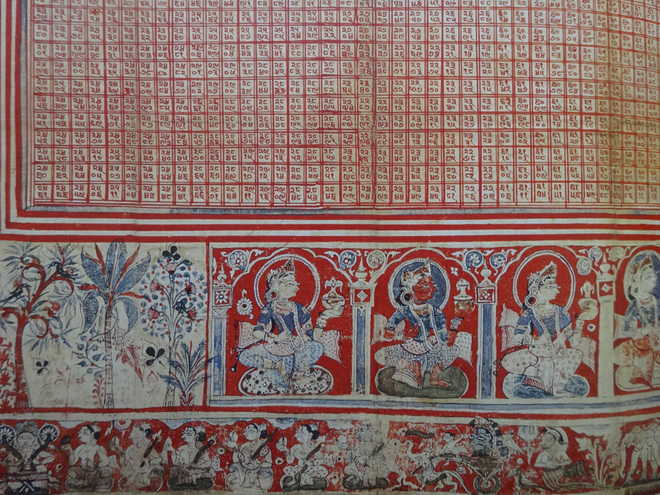

The material comprising the volume draws upon the work done by distinguished early scholars of Jainism, including the late Umakant Shah and Pandit Laxmanbhai Bhojak, as also the relatively more recent work of Shridhar Andhare. And in it we are led into the complex world of vastrapatas that are arranged in different categories: Tantric patas; cosmological diagrams; renderings of pilgrimages, mentally and physically undertaken; vijnaptipatras that were memorials addressed by the members of a community to celebrated Jain munis inviting them to spend their months of retreat in their city. Understandably there is nothing here of the things that most people know Jaina paintings by—kalpasutras and kalakacharya-kathas, sangrahani sutras and the like—because those belong to the category of miniatures. What one encounters here are large works that take the viewer/devotee into domains different from those of the life stories of the great Tirthankaras and Acharyas. Whether these large works serve as aids to concentration, contain subtle speculations about the nature of the cosmos that we are all part of, ensure victory over self or over ‘the other’, there is in them great visual excitement and an invitation to enter the world of thought.

The Arihantas and Siddhas—invoked each day and at each step by the devotee — all appear in these patas, of course, but so do amply endowed maidens—long, inviting eyes, sword-sharp noses, waists so thin as to appear resting on the edge of disappearance—dancing around them and making music as if to distract them from meditating. Mystic syllables like rhim, krim, om mingle with images of sacred feet and sadhakas stand in attendance with folded hands. The central field of an uncommonly large pata features a grid of tiny little squares in which an infinite range of numbers—evidently meticulously calculated and meaningfully arranged—appear, everything surrounded by the most delicately painted borders filled with images of gods and goddesses, equestrian figures and elephants, peacocks and unearthly trees. Everywhere sari-ends flutter in these patas, lotuses bloom, yakshas and apsaras fly about, siddhas and munis remain seated in concentrated thought, and sacred formulae stay inscribed in their allotted spaces. Suddenly, however, one can also get propelled towards elevated spheres as one takes in patas that envision two and a half continents—adhai-dvipas—featuring a conceptual world of concentric circles and bands of oceans interspersed with sacred geometric shapes inside which devotee couples dwell, and every inch of the remaining spaces is filled with minutely calligraphed texts. One can also move, somewhat playfully, towards painted patas depicting ‘snakes and ladders’ kind of dice-games with squares, all organised to make the players rise upwards through good deeds and fall into the nether regions through sins and misdeeds that take the form of snake-heads. Or take in one of the most celebrated documents of medieval times—a vijnaptipatra—which records a ban on animal killing granted as a concession by the Emperor Jehangir to the Jaina community in 1610.

Also read | Art N Soul: The Untold Story of the Sarabhais

In a manner of speaking, with this ‘document’ the volume I speak of lands the reader back in the all too real world that we live in. But, somehow, glimpses of the wondrous, rarefied Jaina world of retreat and meditation, of mystical symbols and unseen continents, keep lingering in the mind.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.