Paithan Ramayana paintings are marked by colourful and innovative designs, and have a highly sophisticated visual language. The paintings were once carried around by bards known as chitrakathis, who used them while reciting the epic as they moved from village to village. Prof. B.N. Goswamy sheds light on the style and performative aspect of the Paithan Ramayana paintings, and how they were used by the chitrakathis to narrate the Ramayana. (Photo Courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, and is reproduced here with permission.

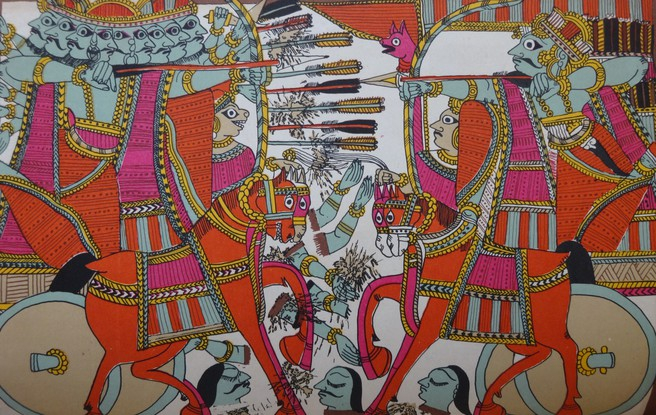

Connoisseurs and collectors of course know about the kind of Ramayana series of paintings of which I write here, but few, very few, of us who live in the North, are likely to have heard of them. Names like Paithan, Sawantwadi or Pinguli—save the first perhaps, and that on account of Paithani saris—all towns or villages in Maharashtra, might mean nothing to most. And yet in and around them has been in existence, for a very long time, a remarkably vigorous style of painting: stylised, intensely colourful, innovative to the extent of being almost spontaneous; folkish but using a highly sophisticated visual language. The works are all on coarse paper, painted sometimes on both sides of a sheet; they are all conceived in series or sets, the themes taken for the most part from ancient classics—the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata Purana, and the like—or local, heroic legends. All of them, like shadow-puppets or kathputli-marionettes, have a performative aspect, for they are carried about in the countryside by bard-like chitrakathis who move about in small groups, and set themselves up for village audiences, showing the paintings, one by one, while singing or reciting the narrative to which they belong. Small crowds of men, women and children sitting outside mud huts, eyes alight with curiosity, the evening turning dark, kerosene lamps, the bard and his accompanists with their simple musical instruments ready to go: one can imagine the magic of the atmosphere. Mani Kaul made a film on this once.

I write this, however, not on Paithan paintings in general but on a particular, well-preserved Ramayana series housed in that uncommon repository of objects of everyday use, the Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum in Pune. A fairly large group from that series was brought out in an elegantly designed publication some 40 years ago—those days are gone now, though—by Maharashtra Tourism. The text was written by Shirin Sabavala; the design was by the famed Chimanlal House; and the pothi-like booklet of close to 50 pages was a pleasure to hold in one’s hands and read from. The images, scattered throughout the booklet in splashing colour, were arresting but so was the text, written as it was with heart, in relatively simple but elegant English, meant alike for young and old. As Shirin wrote it, almost at the very beginning of her narrative there was a passage like this: 'The chitrakathi, like all traditional narrators of the Ramayana would begin with an invocation to Hanumana, or Maruti as he is called in the Deccan.…The eternal devotee, Hanumana is said to listen unnoticed whenever the name of Rama is spoken. He never tires of hearing about Rama and so is believed to be the first to arrive and the last to leave whenever the story of Rama is recounted. The story ends, but Rama Nama is eternal and Hanumana is its Custodian.' Entirely appropriately, the text was accompanied on the page with a striking image of Hanumana from the series: bold and evocative and pulsating with energy.

The tale is told with great relish and understanding in this booklet, but for the audiences who listen to the sing-song words of the chitrakathi, surely no image, no episode, needs to be identified. Everyone, just about everyone, knows the Ramayana, and can recall to the mind all the main events almost instantly: the birth of the four sons to King Dasharatha of Ayodhya and his three queens; the growing up of the four princes; Rama winning the hand of Sita in a svayamvara by bending Shiva’s dread bow; the tantrum thrown by queen Kaikeyi and her asking her husband to exile Rama for 14 long years; the travails of Rama and Sita and Lakshmana among forests and hills; the trick played by the demon Maricha disguised as a golden deer and his getting killed; the abduction of Sita by Ravana, demon-king of Lanka, as a vengeful act; the meeting of Hanumana with Rama and his utter devotion to the Lord; Hanumana locating Sita held against her wishes in the Ashoka grove in Lanka; Rama attacking Lanka with his army of bears and monkeys after building a bridge across the sea; the battles between the forces of the demons and Rama’s army; the final battle in which Rama kills Ravana; and the jubilant return of Rama and Sita to Ayodhya. One can almost see the chitrakathi’s listeners nod their heads in recognition as the images in front of them change from one to the next, and become participants in the action as it unfolds, sometimes even repeating names and words. To them the style of the paintings, with all their abstractions and their wonderful stylisation, presents no problem at all. It is of no concern to them that in these paintings there is neither day nor night; that every single figure is seen in profile, eyes large and staring, features sharply chiselled, bodies nudging the very edges of the paper; or that there is no interest in backgrounds, or depth; and that everything is seen on the same plane.

But the style is heroic and, for us as ‘outsiders’, challenging. The language of the anonymous artist is theatrical, and needs to be carefully decoded even as one savours every phrase, every turn that it takes. The slightest change in the shape of the eyes, the almost imperceptible shift in the outline of the lips, needs to be registered. When we see a face with eyes completely closed, we need to understand that the figure is either dead or has fainted; when a hand is raised to the head, it is a gesture of utter despair; where a blooming tree appears one should be seeing a forest in one’s mind. And so on. For the audience, however, when the show and the telling ends, it is time to rise, and to bring a measure of rice or atta from home, perhaps a few coins, as an offering to the chitrakathi.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.