Recent interest in yogic practices has coincided with the spread of gymnastics and bodybuilding. These were developed as a system of therapeutic movements, which is probably from where the phrase 'mind, body and spirit' emerged. Here we briefly trace the evolution of yoga, from before Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras to the current trends of modern yoga. (Photo Courtesy: [Public Domain])

Think of ‘yoga’ now and a series of contorted postures and asanas immediately come to mind. But interestingly, the association of yoga with ‘posture practices’ is, in fact, a 20th century interpretation of a culture that dates back over 3000 years. Meditation or dhyana, which was once the foremost aspect of yogic practices, has evolved as a parallel global industry in its own right. Two broad categories have now emerged: fitness of the mind, i.e., meditation; and fitness of the body, which is yoga in its various forms.

Repackaged as ‘the New Age wellness form’, the branch of yoga that people are most familiar with is Hatha yoga, based on asanas and pranayama. Hatha literally means ‘by force’. It was only at the end of the 1st millennium CE that references to a method of yoga called ‘Hatha’ began to appear in textual sources. In their highly acclaimed work Roots of Yoga, renowned yoga scholars Mark Singleton and James Mallion assert that a formalised system of Hatha yoga appeared for the first time in the 13th-century Vaishnava text Dattatreyayogasastra.

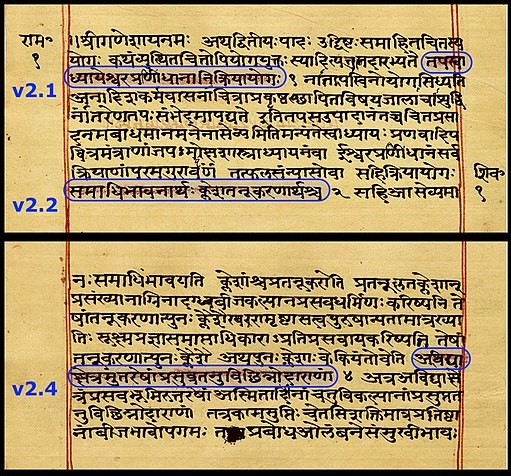

Though Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is considered the basis of the philosophical system of yoga, it is, however, not the earliest text on yoga (Courtesy: Ms Sarah Welch [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Early Documentation of Yoga: Mind over Body

Though Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (4th century CE) is considered the basis of the philosophical system of yoga, it is, however, not the earliest text on yoga. The first references to recognizable yogic practices are found in the Upanishads and the Mahabharata. Graham Burns, a senior Teaching Fellow at SOAS and a veteran yoga teacher, wrote in an article on ‘Meditation’:

Meditative practices, in which the aim is in some way to control and/or quieten the functioning of the mind, are both the real hallmark of the yoga traditions and the link between the diverse sets of practices which, over the centuries, have been given the name ‘yoga’. Probably the earliest usage of ‘yoga’ to designate a form of practice comes from the Katha Upanisad, a text most likely compiled in around the 4th century BCE. There, yoga is defined as the ‘firm reining in’ of the senses and the mind, in order to free the practitioner from distractions.

Here’s how Mallinson and Singleton translated the reference from the Katha Upanishad: ‘When the five senses, along with the mind, remain still and the intellect is not active, that is known as the highest state. They consider yoga to be firm restraint of the senses. Then one becomes undistracted, for yoga is the arising and the passing away.’

As is evident, the practice of yoga during the Vedic period was highly spiritual and focused on the mind instead of the body. At best, it was used to ‘purify’ the body for higher meditation.

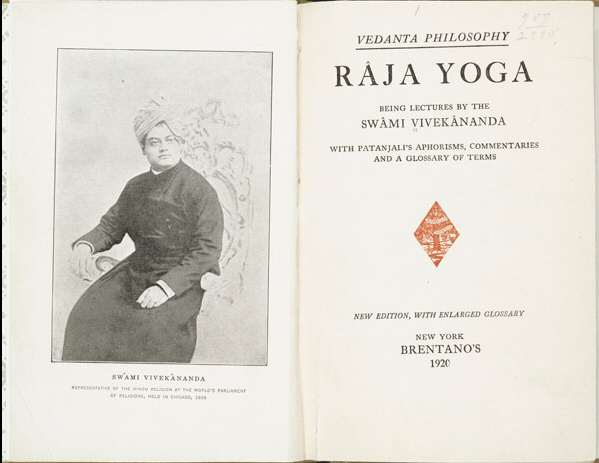

In fact, Swami Vivekananda, who is said to have initially introduced the concept of yoga to the Western world through his rousing speech at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, rejected the idea of asanas as representative of yogic practices in its entirety, considering them only a means to an end. ‘We have nothing to do with it here, because its practices are very difficult, and cannot be learned in a day, and, after all, do not lead to much spiritual growth,’ he wrote in his book Raja Yoga. In the same chapter he called these postures, ‘a series of exercises, physical and mental, [that] is to be gone through every day, until certain higher states are reached.’

The Focus on the Physicality of Yoga

Asanas, according to Mallinson, first found mention in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras—that too as the third of the eight auxiliaries necessary for mastering yoga. Even then, it didn’t focus on the types of postures (although monasteries and temples have long depicted ascetics in yogic positions in temples). Asanas had always been a part of tantric practices but, until around six centuries ago, consisted entirely of seated positions with mudras. ‘The best-known and most influential text on hathayoga, the 15th-century Hathapradipika (‘Light on Hatha’), describes 15 asanas, of which eight are not seated postures,’ he writes.

Swami Vivekananda called the yogic postures ‘a series of exercises, physical and mental, [that] is to be gone through every day, until certain higher states are reached’ (Courtesy: [Public Domain])

However, even though non-seated asanas were not a part of yoga texts, there are mentions of them being used 2500 years ago. Alexander’s entourage in the 4th century BCE found 15 men standing in different postures under the sun for an entire day, and even the Mahabharata mentions ascetics who would invert themselves (bat penance), stand on one leg or hold up their arms for extended periods of time.

Also read | Yogic Body

It was only after the 11th century CE that a whole series of asanas—including the Shavasana (corpse pose), Tapkara asana (ascetic’s posture), Narakasana, Kapalasana and Viparitakaranasana—were documented in Indian texts. Some texts suggest that there are as many as 8.4 million types of asanas, excluding additions from the 20th century. ‘Postures which became part of modern yoga but which had no Indian precedents were classified as asanas; for example, trikonasana, the triangle pose,’ writes Mallinson, adding, ‘As the corpus of texts on hathayoga developed, asana went from being a simple way of sitting for meditation, mantra-repetition and breath-control – taught in passing – to one of its most important, complex, diverse and well documented practices.’

Beyond Hinduism: Cross-cultural References

The first text to teach physical practices under the classification of Hatha yoga was the Dattatreyayogasastra (Yogic Teachings of Dattatreya). It contends that anyone can practise yoga, regardless of their religious orientation. According to the Roots of Yoga:

[If] diligent, through practice everyone, even the young or the old or the diseased, gradually obtains success in yoga. Whether Brahman, ascetic (sramana), Buddhist, Jain, Skull-bearing tantric (kapalika) or materialist (carvaka), the wise man endowed with faith (sraddha), who is constantly devoted to his practice obtains complete success. Success happens for he who performs the practices – how could it happen for one who does not?

Texts that describe both Buddhist and Jain practices describe various asanas, which have also been depicted in the art and sculpture of the time. In the introduction to the brochure on the prolific travelling exhibition ‘Yoga: The Art of Transformation’ (which documents the visual corpus of yoga through the ages), editor Debra Diamond writes:

The pictorial tradition…reveals that yogas was not a unified construct or the domain of any single religion, but rather decentralised and plural. While most objects emerged out of Hindu contexts or depict Hindu practitioners, Jain, Buddhist, Sikh, and Sufi images illuminate patterns of trans-sectarian sharing…Representations of divinized gurus, fierce yoginis, militant ascetics, and romantic heroes epitomize the fluidity of yogic identity across ‘sacred’ and ‘secular’ boundaries.

There have even been studies and references made to the various positions practised by Muslims during namaz, which are similar to yogic postures such as Balasana (child pose).

Related | Yoga and Ayurveda

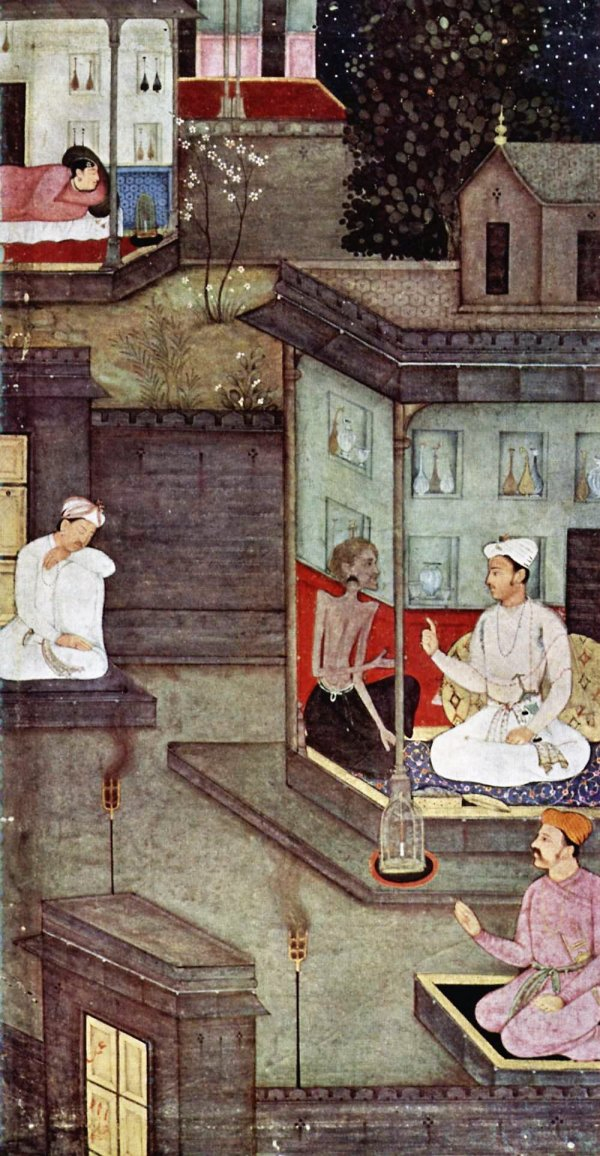

The Mughals, like their Islamic predecessors, were fascinated by yoga and its proclaimed possibilities (Courtesy: Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliyari [Public domain])

Yoga under the Mughals

Historian and author William Dalrymple, in a piece for The New York Review of Books, wrote about ‘a young Hindu khanazad (or ‘palace-born’) prodigy named Govardhan’ in the 17th century, who painted pictures of holy men ‘performing yogic asanas or exercises that aimed to focus the mind and achieve spiritual liberation and transcendence’.

‘The Mughals, like their Islamic predecessors, were fascinated by yoga and its proclaimed possibilities, from its ultimate goal of obtaining enlightenment to even more powerful abilities, such as gaining dominion of the highest gods,’ writes Rachel Parikh, a Calderwood Curatorial Fellow in South Asian Art, in a paper called ‘Yoga under the Mughals’. The sultans were convinced that extraordinary powers could be accessed through the practice of yoga. Emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan not only called for Persian translations of Sanskrit works on yoga, but also the verbal and visual documentation of their personal encounters with ascetics. Most importantly, they called for systematic studies of yoga exercises, so they, like Hindu holy men, could access its powers.

These supernatural powers have been referenced in texts such as the Dattatreyayogasastra, which mention yogic powers that include the ability to fly, to hear and see across vast distances, to make oneself very small or very large, to possess minds, etc. Conversations around these ‘heightened abilities’—especially by the Nath yogis, who adopted and propagated the Hatha yoga tradition—from the 9–10th centuries onwards could have fueled these ideas during the Mughal era.

From Colonial Times to Modern Era

As Singleton says in his essay ‘Transnational Exchange and the Genesis of Modern Postural Yoga’, the predominant connotations of the word ‘yoga’ emerged during a relatively short period in the early decades of the 20th century. This was the result of a complex transnational exchange of ideas and practices within the larger context of what we might term ‘the yoga renaissance’.

However, the beginnings of this exchange can be seen in the late 19th century, with cross-pollination between yoga asanas and Western gymnastics. At the time, Europeans and Americans were simultaneously appropriating and blending new forms of yoga, which was positioned as a ‘spiritual’ practice’. It was also around this time that these ‘body stretches’ began to be associated with Hinduism. Singleton believes that this ideology was furthered by members of the Brahmo Samaj (of which Swami Vivekananda was also a member), as they thought this vision of Hinduism ‘sought to present a unified vision of Indian religion which would counter colonialist claims that Hindus were backward and superstitious in their beliefs and practices.’

Emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan not only called for Persian translations of Sanskrit works on yoga but also the verbal and visual documentation of their personal encounters with ascetics (Courtesy: Meister des Jog-Vashisht-Manuskripts [Public domain])

The timing of this interest in yogic practices coincided with the rise and spread of gymnastics and bodybuilding—which were being developed as a system of therapeutic movements—leading to the emergence of the phrase ‘mind, body and spirit'. Sanskrit scholar Srisa Chandra Vasu, in his 1895 translation of the Gheranda Samhita, said that various postures found in the book were ‘gymnastic exercises, good for general health, and peace of mind’. In India, people such as German bodybuilder Eugen Sandow (1867–1925), and yogi and nationalist Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950) did their bit to combine elements of bodybuilding and yogic asanas.

Thereafter, over the decades, figures such as Swami Kuvalayananda, Shri Yogendra and T. Krishnamacharya were key players in the emergence of yoga as a physical culture on a global platform. Yoga then catapulted to a cult-like status thanks to Krishnamacharya’s student and brother-in-law, B.K.S Iyengar, whose black-and-white images exhibiting contorted asanas have become synonymous with yoga across the world.

Also read | Modern Yoga

In its current form, yoga has transformed from a spiritual pursuit to an $80-billion global industry. In the US alone, it is slated to cross $11 billion by 2020, while in India, the wellness industry is estimated to grow to Rs 1.5 trillion ($22 billion approximately) by 2020. Billions of people practise yoga asanas around the world, and it has even assumed a life of its own on social media, with people practising yoga in scenic locales for Instagram and Facebook.

Part of the allure of yoga—for the general masse—lies in the notion that it is ancient. As Jeremy David Engels, a communications professor at Pennsylvania State University, wrote in his piece for ‘The Conversation’, the fascination with yoga finds root in the ‘“argumentum ad antiquitatem” fallacy – which says that something is good simply because it is old, and because it has always been done this way’. However, at a time when sedentary lifestyles are becoming an epidemic, modern yoga—even though it focuses on the body and not the mind—is not a bad way to hang on to tradition as a means of holistic self-benefit.

This article was also published on The Indian Express.