Visit the temples of Khajuraho, Konark in Odisha, or even the Rani ki Vav stepwell in Gujarat, and you will find yourself in the company of stunning celestial beauties who adorn the facade and walls of these monuments. Unknown to many, and often dismissed as either simple decoration or sensual figurines to please the ‘male gaze’, these surasundaris serve an important purpose. We explore the meaning behind the 16-plus surasundaris found in Indian temple architecture. (Photo Courtesy: Nagarjun Kandukuru/Wikimedia Commons)

‘As a house without a wife, as frolic without a woman, thus without female figures the monument will be of inferior quality and bear no fruit.’

—Boner & Śarmā [i]

Be it the temples of Khajuraho and Odisha or the ornate stepwells of Gujarat, a plenitude of voluptuous celestial female figures in sensual poses adorn the walls of Indian monuments. While these three-dimensional feminine forms might seem like space fillers or simple decorations to the casual tourist or layperson, they are anything but.

According to the Silpa Prakasa, a tenth-century art treatise from Odisha, it was believed that monuments without female figurines were of inferior quality.[ii] However, these figures were not regarded as objects of the ‘voyeuristic male gaze’—as propounded in Western theory[iii]—but were acknowledged to have symbolic importance in the context of the ritual space of stupas and temples. How else can one explain why a nun and a monk would donate two of the most popular female figurines—Sirima Devata and Chanda Yakshi—to the Bharhut stupa in Madhya Pradesh? In fact, these representations on sacred and secular structures may have been considered auspicious symbols, a sign of fecundity based on the biological association of women with fertility.[iv]

Often referred to as a surasundaris (celestial beauty),[v] the Silpa Prakasa categorises these female figurines into 16 types, each with their own attitudes, gestures and expressions. However, in the text, they’re called alasakanya, possibly because of the inherent indolence in their sensual poses.

Also Read | Women in Tantra: The Yoginis of Hirapur

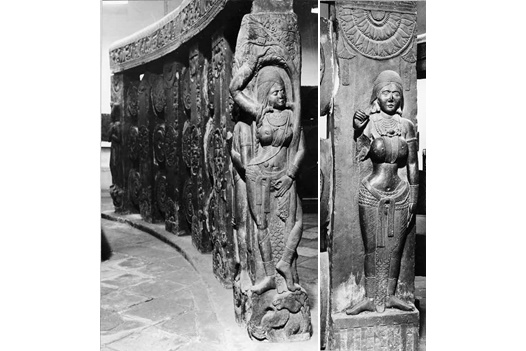

One of the most common and easily identifiable surasundaris is salabhanjika or dalamalika, translating simply to ‘woman and tree’. The earliest-known example of salabhanjika is from Bharhut and dates back to the second century BCE. The salabhanjika form depicts a woman standing in tribhanga pose—wherein the woman’s body is bent at three places—with one hand touching her intimate parts and the other touching (or bending) the branch of a tree. In some cases, the woman and the tree are entwined. Salabhanjika, with her close iconographical association to trees, signifies fecundity. It highlights the role of a woman as prakriti (nature), emanating life into purusha (man) and giving birth to new life forms through their union. One can find variations of salabhanjikas on the facade of most monuments, flanking the principal gods as their attendants as well as on pillars/columns, door entrances, kapilis (the juncture wall between the sanctum and the hall) and janghas (the central portion of the temple wall). However, this placement is actually common to all types of surasundaris.

After salabhanjika, alasa is the most common of the remaining surasundaris found adorning some of India’s iconic monuments. This graceful maiden personifies indolence. She is represented with her hands above her head, reimaging the act of yawning and stretching after a long sleep. Then comes torana, who forms an arch with her hands and leans against a doorframe, perhaps pining and looking for her companion. The resentful/offended manini stands with her back towards the viewers, resentful of her lover’s absence. Also standing with her back towards the viewers is gunthana, the bashful girl who tries to conceal her face (be it with a veil, a flower or a fan).[vi] Mugdha is simple—an innocent maiden endowed with various ornaments. Vinyasa stands with her eyes closed, lost in meditation, with her hands in the gesture of japa-nyasa (meditative posture).

While these surasundaris’ characters are reflected in their expressions and gestures, there are others that use props as part of their sringara (beauty, from the nine rasas), and are appropriately named after the items they possess. For example, padmagandha is usually found standing sideways as she inhales the sweet smell of the lotus flower in her hand. Darpana is always found with a mirror in hand, admiring her own beauty. Ketaki-bharana is adorning her hair with a ketaki blossom. Matrmurti is the image of motherhood, depicting a mother holding her child in her arms. Chamara is usually seen as an attendant to the deities, with a fly-whisk resting against her shoulder. Another celestial figure in a similar vein is sukasarika, who plays with a parrot or a mynah that’s sitting on her hand. Nupurapadika is depicted as touching/playing with her anklets. Nartaki is the female dancer, and mardala, the female drummer.

Also Read | Sculptures of Apsarās and other Celestial Womena at Rani ki Vav

While these 16 delicately carved women have been mentioned in the Silpa Prakasa and are most frequently depicted in Indian architecture, this list is definitely not exhaustive. The Khajuraho temples, which, according to art historian Devangana Desai, boast the highest number of surasundaris, depict numerous representations of maidens disrobing on account of scorpions on their legs. Excluded from the group of 16 surasundaris, these scorpion-bearing women could be associated with the ancient name of Khajuraho—Kharjura-vahaka.[vii] Other depictions include maidens removing thorns from their feet, those with revealing nail marks on their bodies and maidens with dripping wet hair.

It would be nigh impossible to find a temple or stupa bereft of surasundaris, especially in the regions of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Gujarat. As sensuous symbols of auspiciousness, fertility and prosperity, they were placed on the railings of the early stupas of Bharhut and Sanchi. A vast array of surasundaris are present on the Lakshmana and Kandariya Mahadevi temples in Khajuraho, and the Rajarani and Konark temples in Odisha. Among Gujarat’s stepwells, Rani ki Vav in Patan is home to a fair number of these celestial beings.

Also See | Rani ki Vav: Photos of The Twelve Gauris

Although these surasundaris are sensuous in nature, they are rarely considered erotic. A common feature in temple architecture between the second century BCE and the thirteenth/fourteenth centuries CE, these stunning celestial beauties cannot be dismissed as just random space fillers or meaningless decorations. The reason behind their existence is evident—if one only cares to look hard enough.

A version of this article was also published in The Statesman.

Notes

[i] This means that without the crowning decoration of female beauty, the temple would not only lose its artistic quality but its power and efficacy as well. For more details, see Ramacandra Mahapatra Kaula Bhattaraka, Silpa Prakasa, trans. Boner and Sarma (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2005), 38.

[ii] Ramacandra Mahapatra Kaula Bhattaraka, Silpa Prakasa, trans. Boner and Sarma (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2005), 149–71.

[iii] For more details, see Vidya Dehejia, ‘Issues of Spectatorship and Representation,’ in Representing the Body: Gender Issues in Indian Art, ed. Vidya Deheja (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1997), 1−22.

[iv] Stella Kramrisch, ‘The Representation of Nature in Early Buddhist Sculpture (Bharhut−Sanchi),’ in Exploring India’s Sacred Art: Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch, ed. Barbara Stoler Miller (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1994), 126.

[v] Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol. 2 (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1976), 338.

[vi] Ibid., 165.

[vii] Devangana Desai, The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho (Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies, 1996), 176.