Cities are excellent reminders of our cultural memory, aspirational projections, our successes and failures in establishing cosmopolitan spaces of collective living. We look at the imaginaries of the cities in Indian epic literature. (Photo Source: Vaibhavsoni1/Wikimedia Commons)

William Blake once wrote, 'Whatever is proven today was once imagined'. Would that be true of the cities? Were they once imagined? What would classical Indian literature say about cities?

In Sanskrit, it was imperative for kavya (epic) literature to have 18 kinds of descriptions, which included sunrise, the sea, the rains and similar natural elements. One of the most important among the 18, which is not a nature description, is the hero's journey through a city. Though there is no such fixed rule for Tamil kavya literature, in both in Tamil and Sanskrit classical literature, we read greatly visualised descriptions of cities. For instance, in Valmiki's Ramayana, we read an idealised description of Ayodhya, a model city known for its high moral codes of conduct. Valmiki says that nobody in Ayodhya would kill a fleeing enemy. Writing about the moral order embodied in cities, poet and scholar A.K. Ramanujan observed in his essay, ‘Towards an Anthology of City Images’, that ‘Ayodhya and its moral order is symbolic of Rama himself a god descended to right all wrongs; it is in fact identified with the perfect hero.’ The character of a city being conditioned by its learned citizenry is further elaborated in Kamban's Ramayanam in Tamil. Kamban compares the city of Ayodhya to a grand tree, the seed of which is education, its branches critical inquiries, its leaves good characters of the citizens, its tender leaves and buds love, and its fruits ethical pleasures (Balakandam, Nakara pattalam stanza 75). The crown prince of Ayodhya, Rama, is a collective representative and a reflection of its informed citizenry. In contrast to the high thinking and simple living that lend qualities to the city of Ayodhya, Kamban's description of the city of Lanka, Ravana's capital, shows its opulence, revelry, debauchery and decadence Kamban's Lanka shown through the eyes of Anuman (Hanuman in Tamil) may easily compare with the depiction of a modern city. Ashoka forest, where Sita is imprisoned, is the only greenery visible to Anuman in Lanka. Anuman sees in the city, opulence devoid of any character. T.S. Eliot, a modernist poet of the city life would have described it as an 'unreal city' and he would have seen in Ravana with his 10 heads, a Prufrock, a deeply divided man who is unable to discriminate between love and desire, right and wrong, and heroism and a false sense of superiority.

In the Mahabharata, Hastinapur was the hereditary capital city of the Kuru dynasty. The Draupati Ghat in Hastinapur on the banks of Budhi Ganga are a reminder of the city's association with the epic. (Photo Source: Giridharmamidi/Wikimedia Commons)

The City as a Political Power

In the Mahabharata, Indraprastha (the Pandavas’ newly built city) and Hastinapur (the hereditary capital city of the Kuru dynasty), never exhibit any moral order. Unlike the Ramayana, the Mahabharata presents cities as seats of political power, palace conspiracies and intrigues. Indraprastha's architectural marvels, the polished surfaces of the walls and floors of the palace, and its beauty of being a planned city evoke deep envy in Duryodhana. When Duryodhana slips on the polished surface of the floor of the Pandava’s palace in Indraprastha, Draupadi laughs at him, which profoundly offends him. It’s from there that a Tamil proverb warns against the woman laughing out loud in public, saying that a woman's laughter could bring about a Kurukshetra war and great destruction.

Cities also Represent Desires

Italo Calvino famously wrote in his novel, Invisible Cities, ‘With cities, it is as with dreams: everything imaginable can be dreamed, but even the most unexpected dream is a rebus that conceals a desire or, its reverse, a fear. Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.’

One may see in the city of Puhar a place of wealth, liberal love and pleasure. In the ancient Tamil epic Silapathikaram, we read about the coastal city of Kaveripoompattinam, also known as Puhar. As a city of merchants, Puhar boasted off wealth and pleasure. Puhar possessed large storage houses for keeping the merchandise, but there were no guards or doors. There was a miraculous pond where the lame and leprous by bathing in its waters or going around it could recover their strength and health. The crossing of four roads in Puhar was guarded by a statue whose lips never parted, but it shed tears when the monarch failed to uphold justice. Sacrifices and rituals characterise the daily lives of the people. Narrated through the eyes of a villager who arrives at the city with his lady love, Silapathikaram depicts the festival of Indira and the pleasures of art and dance in the city. Madhavi—the courtesan and the lover of Kovalan, the protagonist of the epic—plays the harp and sings songs at the seashore. We read about thousands of men and women dancing, drinking, merrymaking and loving on the shore on a full-moon night. The city of desire and wealth also presents an image of endless love and happiness. Narrated through the eyes of a villager, Puhar fuses desire and fulfilment.

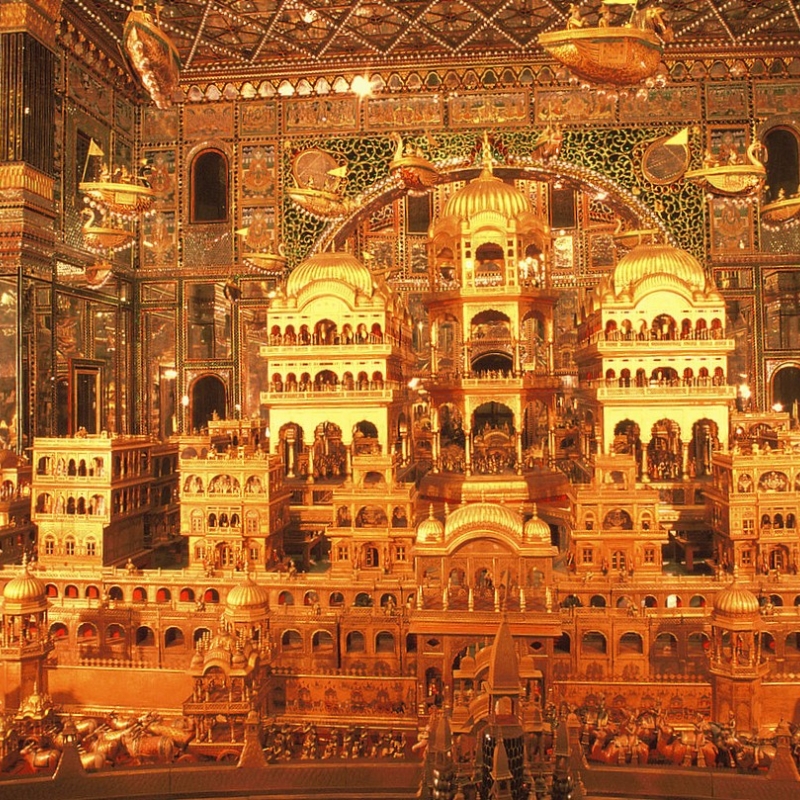

In Ramayanam, Kamban compares the city of Ayodhya (as seen in the folio above) to a grand tree, the seed of which is education, its branches critical inquiries, its leaves good characters of the citizens, its tender leaves and buds love. (Photo Source: Ramnath Bhat/Wikimedia Commons)

The City and Destruction

Silapathikaram presents the image of another city, Madurai; but it is described differently. What we see in Madurai is a highly fortified city with its military defence. In the canto on the description of the city (Oor kaan kaathai—Madurai Kantam) we read about the streets of the king, the merchants, goldsmiths and residents. Madurai of Silapathikaram exhibits great order with the king as its centre. Puhar is organised and orderly too, but it is decentralised. As a fortified city, Madurai guards its citizens, and as the story develops, we see that Madurai is deeply suspicious of outsiders. So it is easy for the goldsmith to lie against the innocent Kovalan, an outsider, and get capital punishment for the latter. The Pandya king, without even verifying the evidence of the case against Kovalan, punishes him. Kovalan's wife Kannagi immediately sees through the corrupt nature of the city that permeates from the ordinary citizen like the goldsmith to the king. Transformed by her fury, Kannagi cuts her left breast, throws it on the city of Madurai and burns it down. Kannagi, in her grand motherliness, allows the children, women and old folk to survive the fire and destruction caused by her left breast. Madurai's order and authority lay centred in the idea of justice, and when an innocent man is wrongly punished, the city deserves to be destroyed.

The metaphysical order of Ayodhya, the debauchery of Lanka, the political powers of Indraprastha, and Hastinapur, the pleasures of Puhar and the social justice (or its lack of it) of Madurai present excellent examples of the imaginaries of the cities in Indian epic literature. They are reminders of our cultural memory, aspirational projections, our successes and failures in establishing cosmopolitan spaces of collective living. Whatever their evolutionary prospects are, cities are always desirable. That is why a famous Tamil proverb (Kettum Pattanam Ser) advises that even if you are ruined, somehow reach a city.

Views expressed are personal.