Once in a while the routine of daily life is broken by fleeting moments that take us on a journey down memory lane. One such moment happened when I was watching the movie Tintin with my seven-year-old daughter Sasha. She pointed to a device and curiously asked, “What’s that?” “That’s called a typewriter,” I said, “One can type with it directly on paper.”

The first commercial mechanical typewriter was produced in the U.S. in 1867. The invention of the typewriter revolutionised writing and introduced a new form of hand-eye coordination based motor skill—typing. Patronage by famous writers and authors—like Mark Twain, who was the first to submit a manuscript (Life on the Mississippi) typed on a typewriter, and Jack Kerouac, who could type 100 words a minute—made the typewriter an icon of the intelligentsia. After dominating for more than a century, the typewriter started to face stiff competition from the increasing popularity of personal computers and the introduction of low-cost, high-quality laser and inkjet printer technologies. This was quickly followed by the arrival of the internet and the pervasive use of web publishing, e-mail, mobile phones and other forms of digital communication.

In today’s age, hardly anyone still maintains an old typewriter at home, let alone offices. Museums in India do not display them, as the device is not yet considered as valuable industrial heritage, and old typewriters are sold as junk. I went around asking my friends if they had any information on typewriters still used in everyday life. One of them informed me of two kind of professionals who continue to use the typewriter; they are lawyers and typists outside courts in India.

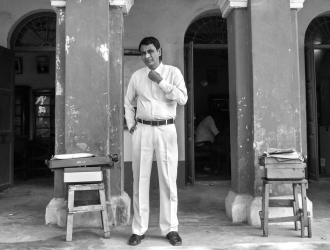

I found my way to the Cooch Behar District Court, camera in tow, looking for the elusive typewriter and their modern practitioners. When I reached the premises, to my pleasant surprise, I noticed typewriters lying around packed and unattended, covered with plastic bags. Within the next hour, the court premises came to life, bustling with advocates, notaries, clerks, attorneys, lawyers, policemen and litigants. Soon the typists started setting up their business for the day.

There I met Ratan Dey, who has been working for more than 22 years and is regarded one of the most experienced hands. He prepares affidavits and agreements for land purchase deals. He uses a very old model of a Remington Typewriter manufactured in 1980. The classic brands, Godrej and Remington, are the most popular typewriters used here. The lesser-known Halda and Facit models are also used by a few. Not all the typists are as experienced as Mr Ratan though. Some of them have just started and inherited their typewriters from their fathers. Khagen Das, 35, is one of them. He started typing here three years ago after initially trying his luck as a computer operator.

I asked them, “Aren't computers replacing them?”

Mukul Kinnar, a senior typist who has put in over 25 years of service, sets things in perspective, “The typewriter may have lost the battle against the computers in other sectors, but for judiciary work, there is no replacement for typewriters. Majority of the people come to us with documents in illegible handwriting or old paperwork. We, the experienced typists, analyse them, interpret them, and compose it in a manner and language that is acceptable to the court. Inexperienced computer operators cannot do that.” Mr Mukul further elaborated “Above all, loyal customers and senior advocates prefer their documents typed on a typewriter. As a result, computers can’t invade this space. Yes, there are a few who use computers, but the number is very less.

Another great advantage of typewriters is they do not require electricity, so it’s perfect for setting up anywhere. Maintenance is cheap and, if well maintained, they can be used for 25 years or longer. Computer ink is costly while a typewriter ribbon costs only 60-70 Rupees. “So how much does it cost to type a page,” I asked. “The price depends on the nature of the document. For example, a simple affidavit costs Rs.10 per page.” “And how much do you earn a day?” I enquired hesitantly. On a good day, they earn around INR 100–150, and even less on other days.

In the course of next few months, I travelled to various small cities in West Bengal to document the stories of tenacious typists and their typewriters. I came to know that in April 2011, Godrej and Boyce, India’s last-surviving typewriter makers, closed shop, unable to find new orders. Though electric typewriters are still made in some countries, Godrej and Boyce were the last to produce mechanical typewriters. This sudden demise caught typewriter enthusiasts by surprise, given the company was making 50,000 machines a year even in the 1990s!

One day I took my daughter to meet the typists and they were kind enough to explain typing process to her. After typing a line, my daughter asked a very important question: “So how do you correct a spelling mistake?” “You just hit backspace and put an ‘X’ on it,” Bijon Roy, another typist, answered with a smile. Bijon was curious to know why I was taking pictures of the typewriters. I said I was anxious that these machines might get extinct soon. He laughed and dismissed my concern, “Don’t worry, typewriters will survive.”

Bijon might be optimistic, but whether or not the typewriter will stay relevant in the future is yet to be witnessed. Although the QWERTY keyboard layout was first developed for the typewriter, which is now applied ubiquitously on all keyboards and smartphones, operating a modern keyboard is vastly different from the mechanical operation of a vintage typewriter, which takes great skill, training and specialised knowledge. Whether this knowledge will be transferred to a new generation of typists in the future is uncertain.