Velvets: The Product of Royal Life and Intricate Art

Wrapped around luxuriously and displayed to flaunt wealth, such was the epitome of popularity achieved by velvet in its glorious days of yesteryear. Velvet, technically defined as a warp cut-pile weave fabric has been a cloth of interest for courtly families owing to its lustrous yet elegant look, combined with the extensive labour that is involved in its production, though the manufacturing technique changed with the mechanization of this fabric’s production. Silk, wool and cotton were the common fibres used for weaving velvets. During its 600 years of glory, silk velvets were the most preferred and considered the most royal, followed by cotton, and wool was the least manufactured (Raheja 2017:3).

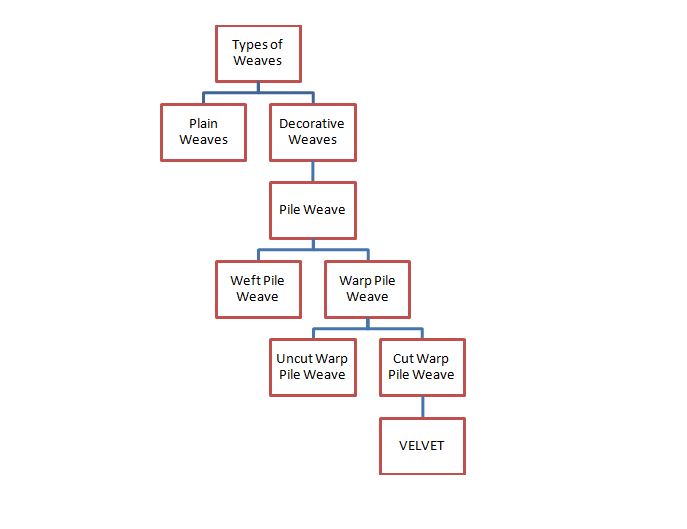

Velvet fabric falls under the category of warp cut-pile fabric. It is important to understand this technical definition. Weaves are classified into two broad categories, namely plain weaves and decorative weaves. Plain weaves are formed by bringing about variation in the interlacement pattern of the warp and weft yarns, i.e., the two set of yarns used to weave a fabric. There are no supplementary yarns used. Decorative weaves on the other hand use a third set of yarns to create patterns in the fabric being woven. Under the category of decorative weaves, when a set of supplementary yarns isused in the warp direction, and these yarns create loops and further these loops are cut to form tufts, this technically forms a velvet fabric. Innumerable weaves can be mentioned under each category due to the variations that can be carried out in the interlacement pattern, however, for the sake of understanding the construction of velvets, subdivisions of the relevant categories have been mentioned.

Classification of velvet

Evidences of weft-cut pile fabric of linen have been found in Egypt as early as 2000 BCE, however technical understanding puts into perspective the fact that this fabric is not a velvet fabric in its true sense. Linen cut-warp pile fabric has in fact been found in Egypt itself dating back to as early as the fourth or fifth century BCE.

Over the years, any fabric with tufts came to be labeled as velvet, whether the fabric was woven in the same manner or not, whether it was looped or cut, produced through the technique of weaving or by knotting.

One such textile often referred to as velvetis the tufted carpet. Carpets are manufactured by laying one set of yarns vertically. Threads of the colours required to form the desired pattern are looped around these vertical yarns, with the front displaying loose ends and the reverse showing looping of threads around the previously laid vertical yarns. This formation of tufts gives an illusion of a velvet fabric. Although visually they might be similar, the technique of manufacturing is what differentiates true velvets from carpets.

The manufacturing of carpets requires the use of a vertical loom, whereas the manufacturing of handwoven velvet is carried out on a horizontal loom, specifically a drawloom. A simple handloom allowed the production of a plain woven fabric, whose patterning, if desired, becomes a very tedious and cumbersome process. However, with the introduction of the drawloom, the patterning of fabric became possible through the manipulation of threads to execute complicated designs (Boudy 1979:124). Known to have originated in the Far East, this horizontal loom made its way to Egypt through trade, where the dry climate and religious practice of burying the belongings of the deceased, resulted in the survival of woven velvet fabric. However, the scarcity of velvet fabrics and the workmanship makes analysts feel this could have been an imported fabric (Bellinger 1955).

The mechanism of the Egyptian loom used to weave warp pile fabrics has been described by Bellinger thus:

two pile warps (are) carried with each fourth cloth warp. Pile comes to the surface in every second or fourth shed. In the pile sheds there are two shots of weft, one before and one after the pile tufts, which hold the pilein place when firmly beaten in. (Bellinger 1955)

In other words, every fourth heddle carrying the warp yarn has two extra warp yarns with it, which will eventually form the pile in the woven fabric. To weave the weft yarns in a fabric, a shed is creating by raising a selected number of warp yarns, while keeping the others in place. Depending on the design and weave to be created, either a single or multiple weft yarns can be passed through a single shed. On weaving the velvet fabric, the supplementary warp yarns come in line with the rest the surface to form the pile after a few weft yarns (depending on how many weft yarns have been inserted in each shed) and are secured with a weft yarn on either side, i.e., before and after the formed pile. This is a description of one of the earlier velvet fabrics woven on a drawloom.

Of all the materials used for producing velvet, silk was most preferred by royalty due to its elegant sheen, which could not be imparted by linen, cotton or wool. The Egyptian Predynastic Period (c. 6000–c. 3150 BCE) marked the beginning of trade between ancient Egypt and the rest of the world (Mark 2017). Whether Egypt was the sole producer of velvet cannot be ascertained, however trade must have ensured the travel of the technique from one land to the other. Although the Silk Road played a pivotal part in ensuring the trade of silk from China to other parts of the world such as Persia and Rome, the discovery of an Egyptian Mummy with silk dates silk trade to 1070 BCE. However, with the disclosure of the secret of silk manufacturing during the sixth century, silk became more widely available and China could no longer demand the exorbitant price that it was previously charging. The Middle East has been known for its artistic advancements. The indigenous availability of silk, especially in theMiddle East, allowed for the production of artistically intricate products, one of them being velvet.

With the coming of the Mughals to India, velvets were extensively promoted. The drawloom undoubtedly was a part of the Indian weaving culture even before the Mughals, having presumably been introduced to India in the second millennium. It is not known when exactly velvet production started in India, however the tales of travelers from the 10th to 15th centuries mention eastern and western India as sources for velvet or velvet-like textiles (Jain 2011).

At its peak, many variations were seen in the types of velvet being produced, each one having a unique quality. The variation was brought about either at the weaving level, or post weaving with a surface application of a particular kind to obtain the desired look.

Types of velvet

Plain Velvets: When the entire fabric is covered inpile, it is known as plain velvet. The terminology kadife was used in the Middle East, specifically Bursa to refer to plain velvets (Delibas 1986).

Embossed velvets: Although lesser pieces exist in India, embossed velvets were more common in Persia. Stamps were used on prepared plain velvet, which crushed the pile in certain areas according to the design to be achieved. In terms of literature, however, not much information is provided.

Painted velvets: Due to the technique being simpler than the others, these velvets were of the cheapest quality and were produced at Cambay. They were stenciled or hand painted with gold colour, similarin style to thehangings of the Mughal period carrying tree patterns or the portrait of Akbar.

Embroidered velvets: Due to their exquisite look and extensive use of gold and silver, embroidered velvets were mostly used for ceremonial occasions. Metal threads were used to embroider over plain velvet to give a rich and expensive look to the garment.

Ikat velvets: Incorporating the technique of Ikat dyeing, withsilk being the yarn of choice, Ikat velvets were one of the most expensive forms of velvet produced. Due to the intricate methodsof Ikat production, the rate of production was extremely slow, however, this is the very reason for the elite status of these velvets.

In Gujarat, Ikat velvets were referred to as patani, a part of the category of velvets called kathivu which was derived from the Arab word for velvets, al-katifa (Dhamija1989).

Voided velvets: Known as makhmalaizarbaft in India, voided velvets have to be of the finest quality.Lahore, Gujarat and Kashan were the main centres of production.As the name suggests, the pile was present only in sections of the fabric, and the rest remained voided. The more exclusive pieces consisted of a gold or silver ground with motifs designed with the pile.

The voided section generally carried extra weft gold thread twisted over silk or gilded paper known as lamé. Voided velvets were most commonly used during the time of the Mughals.

Brocaded velvets: Combined with voiding and using the technique of brocading, these velvets used metallic threads, either in the void or in the velvet. This earned them the name ofmakhmalizarbaft(cloth of gold) in India, however, in the Middle East this type of velvet was known as Caima.

The handling of brocaded patterns being worked with extra weft threads, along with velvet patterns, with the use of multiple extra warps, required total mastery over the weaving techniques. This style was developed effectively in India during the Mughal period.

With the production of a variety of velvets came multiple uses of these extensively woven fabrics. Apart from types, velvets can be classified based on usage: self adornment, religious purposes, upholstery, adornment of animals, arms and armour, and miscellaneous uses.

Self Adornment

Adorning the self with luxurious goods to affirm one’s position and power is a common practice. The richness exuded by velvets made it one of the preferred choices for royalty to do this. Velvets were mostly used in male garments, either for formal occasions or as evening gowns for winters.For self adornment, velvets were used for:

Surface fabrics of garments: The thickness of the fabric made it ideal for winterwear. Garments such as sherwanis, achkans, atamsukhs, ghughis,angarkhis, farzi, sadri, pyjamas, breeches, evening gownsin velvet are stored and on display in the Mehrangarh Museum Trust Collection, Jodhpur, and Sawai Man Singh II Museum Collection, Jaipur.

Lining of garments: Velvet was often used as a lining for other fabrics. A few objects in the Mehrangarh collection such as sherwanis had a lining of a cut pile weave fabric. Whether those fabrics are technically velvet fabrics is debatable. Moreover the finish of the fabric hints at its production towards more recent times. Since thorough weave examination of the object was not possible, the possibility of it being a velvet fabric could not be completely ruled out.

As lace and appliqué work on garments: Garments in the Mehrangarh Fort collection include not onlysherwanismade from velvet, but also those which may be crafted from a material such as brocade orlampas weave fabric, but the presence of velvet is in the form of either patches at the shoulders and nape of the neck, or as lace at the inner edges of the torso and cuffs, with additional embroidery work carried out on them.

Footwear: Velvet was also used to line the juttis(slippers) worn by royalty. These objects are more recent, dating back to only the 19th or 20th century, when juttis were the preferred form of footwear.

Accessories: Purses were a common accessory carried by men and women. Locally known as batua, small coin purses were made of velvet with gilded zari thread embroidery as embellishment.Hats were another accessory that were made of velvet.

Religious Purposes

Worldwide, velvet was used for various religious purposes:to drape those holding high religious office, as a backdrop for religious depictions, and as covers for religious books, such as the Quran.The Calico Museum houses a 19th-century chasuble (ornate vestment worn by a Catholic or High Anglican priest when celebrating Mass), which is an embroidered velvet piece. The Calico Museum collection also has on display a 19th-century zari-embroidered velvet cape worn by an idol of Saint Mahavir.

Upholstery

History is not short of evidences of velvet being used for upholstery. From tents to floor spreads to wall hangings, velvets were a preferred choice for their supple feel. Apart from these, the extensive collections at the Mehrangarh Museum Trust and the Sawai Man Singh II Palace house objects such as bolster covers, fans and other items of palace décor which were most often wrapped in velvet. Palanquin covers, howdah seats, cradle linings, thalposh (dish covers), parasols, insignia etc. were also decorated with velvet as the fabric of choice.

Adornment of Animals

The royal animals were as luxuriously decorated as the kings, if not more. Elephants and horses, the more commonly used animals for processions and other regal ceremonies, were decorated with velvet fabric. The elephant trappings and the horse saddle cover and face brace too were made of velvet.

Arms and Armour

Sword covers, gunpowder flasks and small purses that were carried by the royals were also in the formof a velvet covering. Sometimes the base material would be different, for example leather, and that would be lined with velvet on the surface.

Miscellaneous

Apart from the aforementioned uses, velvet was also used for luxury items such as chess mats and book covers.

With the onset of the industrial revolution, not only was the exquisiteness of the handmade goods replaced with mass-produced cheaper imitations, the fierce competition with the machines disheartened craftspersons. They were going out of business and the only way they could sustain themselves was to get on the industrial bandwagon. Leaving their heritage behind, they began to work in factories, not necessarily in their field of expertise. The question was not whether their craft was important or not, but more about where the next meal would come from. It was only over time that the value of these handicrafts began to be widely realized, however, in the times where these goods were commonly available, and were the regular commodities rather than the rare ones, it could not have been anticipated that this fate would overtake them.

With the mechanical productionof goods, where velvet was once affordable only by the elite, it was now accessible to the common people due to the lower cost of production. Where once even an inch of fabric would take hours to be woven, not taking into account the months of preparation before the weaving process began, a high speed powerloom could weave yards and yards of fabric in a single day. The availability of these goods brought about a sense of equality among people. The mechanization of velvet weaving, however, brought a drastic change in weaving techniques. Where satin and twill weaves were used to hold the pile in place, the powerloom technique varied in many respects:the first and foremost being that on a power loom, two lengths of fabric are woven together, with the pile surfaces facing each other. Thus, the production of material doubles. Two fabrics are woven and the pile is an extra set of yarns that interlaces two individually woven base fabrics. The yardage thus produced is cut horizontally from the middle, forming tufts on two separate fabrics. Handloom velvet would require at least twill or a satin weave to successfully weave a velvet fabric, however with the powerloom, the simplest of the weaves, the plain weave, is sufficient to ensure the production of a velvet fabric. To hold the pile in place, the power loom technically uses either the ‘W’ or the ‘V’ interlacement of the pile yarn to the woven base fabric. Interestingly, the invention of knitting machines further decreased the demand for woven velvets. Knits gave the added benefit of stretch and of conforming to a three-dimensional form without forming bulges. Due to this advantage, knitted velvets became more popular for clothing.

Over the years, leaving asidethe decline ofhandloom velvets, the production of power-loom woven velvets too has reduced to very few companies, located specifically inthe areas of Agra and Panipat. One such manufacturer is Taj Velvets located in the industrial zone of Agra. Taj Velvets manufactures only woven velvets. The variations seen in the velvets they produce are immense. With the combination of various fibres, natural and man-made, for base fabric as well as the pile, velvets are manufactured for any use imaginable. With the introduction of synthetic fibres such as nylon, polyester, rayon etc., further strength is imparted to the fabric while reducing the cost in some ways. Although a pure silk velvet is not in regular production due to its extremely low demand, it can be made on order. With the focus now on cost effective and durable productions, pure silk velvets are not able to compete with synthetic mix fabrics. Nowmainly used for upholstery, woven velvets have a very niche market.

By contrast, knitted velvets are being purchasedfor every use possible. With their easy accessibility and low cost, velvets have now become a fabric of the masses as opposed to the fabric of the rich as in the past. The centres which previously produced the handwoven velvets ofIndia are still producing velvets, however it is now all about knitted velvets. Gujarat, a major centre of handloom velvet is now famous for knitted velvets, with in all likelihoodnot even a single manufacturer producing woven velvet, let alone handloom velvet.

Whereas earlier velvets were mostly seen in men’s garments, now theyalso seem to be a preferred choice of females for a formal look. In the present day, velvet has become synonymous with any form of pile or napped fabric or adhesive bonded fibre fabric.

Amidst the mass production of velvets, a small house on the outskirts of Banaras in district Cholapur belonging to the Ansari family continues the tradition of handloom velvet weaving. After the technique of velvet weaving became practically extinct, Rahul Jain, textile historian, set up a velvet handloom which would mimic the weave and style of the velvets that were produced in the past. This velvet does not have a market in India; however, its export helps it carve out a niche for itself.

Whether the trajectory taken by velvet manufacturing is a bane or a boon is a matter of perception. For those who value cultural heritage, it may seem like a loss, but for those who have longed to be able to afford this fabric of luxury, modern-day technology has made them come closer to their dreams. But it is true that the level of intricacy, abstraction, concentration, perseverance and sheer of sense of passion that radiates from the exquisite surviving velvet pieces truly represent works of art to marvel at. And the responsibility to keep alive this passion and cultural heritage is carried on the shoulders of Cholapur, Banaras.

References

Bellinger, Louisa.1955.‘Textile Analysis: Pile technique in Egypt and the Near East’, Part 4, The Textile Museum,Workshop Notes12:1–8. Washington, D.C: The Textile Museum.

Boudy, E.1979.The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present.New Hampshire:University Press of New England.

Delibas, S., J.M.Rogers, and H. Tezcan.1986. Topkapi: Costumes, Embroideries and Other Textiles. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Dhamija, Jasleen, and Jyotindra Jain. 1989. Handwoven Fabrics of India. New Jersey: Grantha Corporation.

Jain, Rahul.2011.Mughal Velvets in the Collection of the Calico Museum of Textiles.Ahmedabad: Calico Museum of Textiles.

Mark, J. 2017.‘Trade in Ancient Egypt’, online at https://www.ancient.eu/article/1079/trade-in-ancient-egypt/ (viewed on February 10,2018).

Raheja, Radhana. 2017. ‘Voyage of Metal Threads through the Age of Flamboyancy’, TCRC e-Journal1.2.

UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/about-silk-road (viewed on February 18, 2018)