While there is much being planned in India in the field of urban development and urban regeneration with schemes such as HRIDAY and Smart Cities mission, there is little talk about the development of smaller towns such as Paithan. This article aims to highlight the potential of integrated heritage-based tourism with urban development for the town of Paithan. Between 17th and 18th centuries the town flourished due to its political and religious prominence, economy, and patronage of its traditional industry.

Later, Paithan could not thrive due to a lack of economic potential and migration of many weaving families to Yeola. The inadequate development policies and dying Paithani industry led to the degeneration of Paithan’s heritage and urban quality of life. It now appears to have succumbed to the urbanisation all around it. Paithan today has a strong potential for tourism with its numerous Wadas and the Paithani industry. But at present, this traditional heritage and the economic potential of the town are struggling to survive. This article looks at the town’s heritage—physical and economic—as a catalyst in the town’s urban development.

Evolution of Urban Form

Paithan, a small town with a modest population of 34,556 people, is located on the banks of river Godavari. Its existence can be traced back to 2nd century BCE when it was made the capital city of Satavahana kingdom. Known as Pratishthana, the settlement came under various rulers, the Vatakas , Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Yadava, Khilji dynasty, Mughal rule, and the Peshwas. Paithan flourished the most as a significant city during the Peshwa rule. This was also the time when the Sahukar (Moneylenders and Landlords) flourished and gained importance. Paithani silk became popular amongst the royals, and thus Paithan became an important silk and textile centre of the era. Paithan also has religious significance for Hindus and Jains. It is called the 'City of Saints' by many because of the many saints that have preached on its land.

Urban form is defined as the physical characteristics that make up built-up areas, including the shape, size, density and configuration of settlements. It evolves over time responding to the various geographic, socio-political, economic and cultural contexts. The spatial composition of a city or a town often shows evidence of the prevailing societal conditions. Paithan’s architecture style, its movement network and settlement pattern appear to be heavily influenced by the Paithani weaving activity. A lot of present day Paithan’s layout is a result of the socio-economic conditions of 17th-century Paithan. Even though the status of Paithani weaving is no longer the same as it was a century ago, it has left huge traces on the urban form of Paithan.

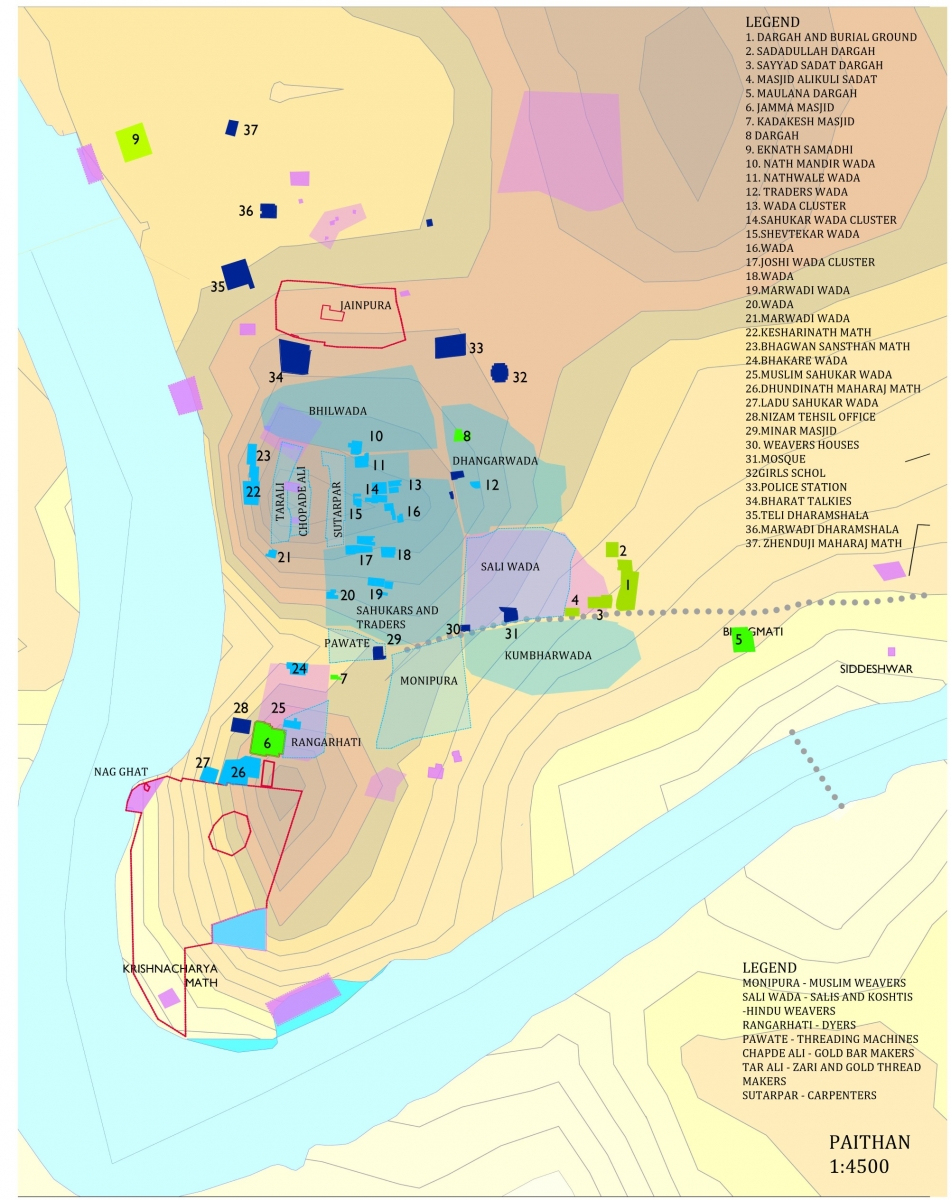

Figure 1.1a shows important landmarks and settlements within the city of Paithan during the 17th century. (Graphic credit: Belapurkar 2016)

Research shows that the city evolved the way it has in response to the needs of the weaving industry. The flow of raw material, processing of raw materials, the communities involved in various processes and the political patronage are all the factors that resulted in the settlement pattern that we see today. The architecture in Paithan is heavily influenced by the Paithani industry. Be it the dwellings of the weavers or the grand Wadas of the Sahukars, Paithani weaving has evidently played a role in the architecture of these houses. Traditionally, most of the weavers’ families worked from home, hence the handlooms and storage had to be accommodated within their residences.

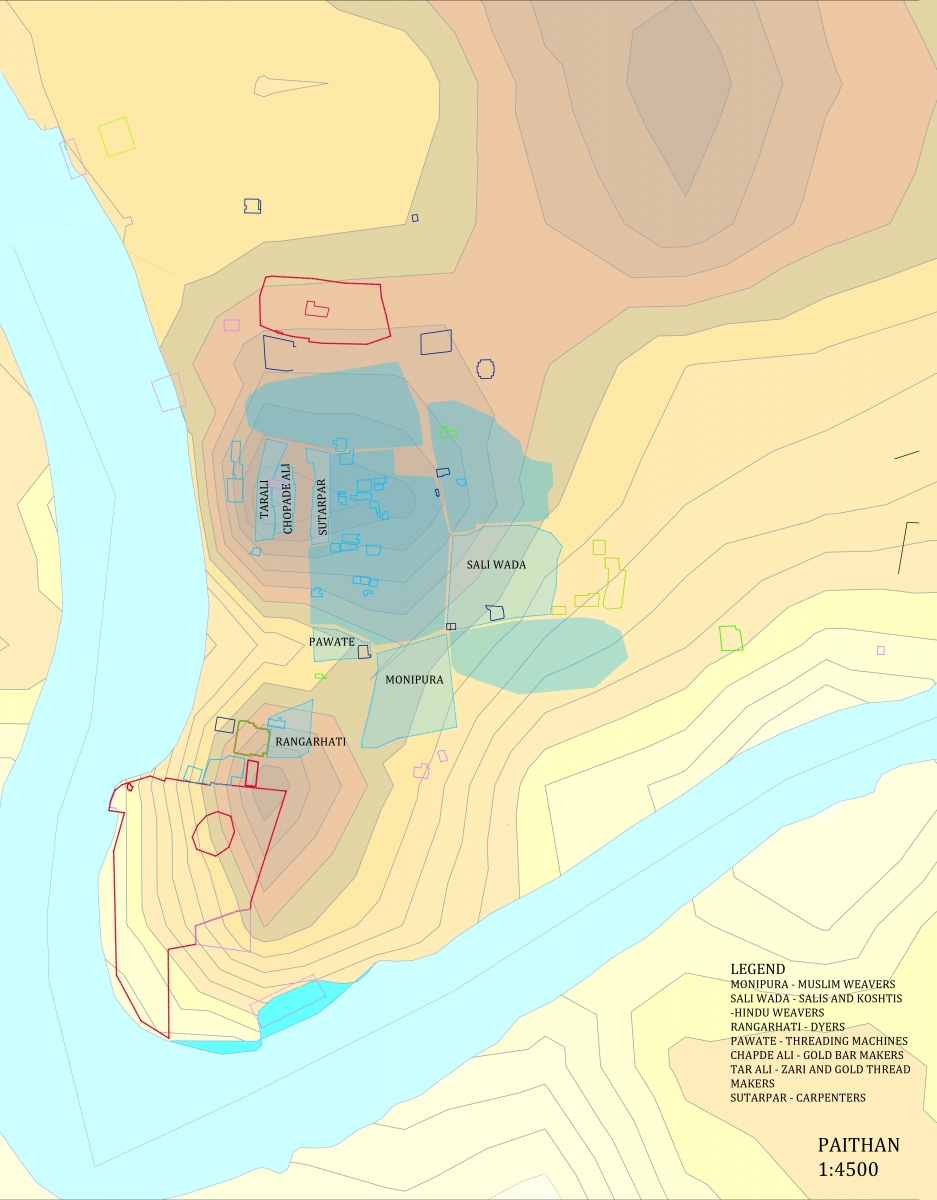

Figure 1.1b shows different communities involved in Paithani weaving, settled strategically within the town. (Graphic credit: Belapurkar 2016)

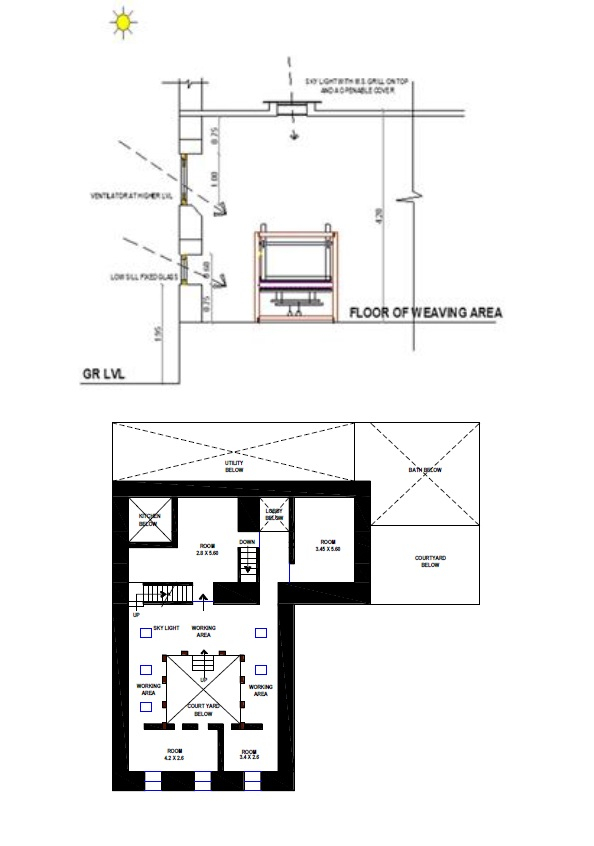

Extensive use of the outdoors, courtyards, the multiplicity of spaces used, simple sequences that clearly define space use in the context of the family habits, occupation etc., are some of the dominating characteristics of the traditional dwelling. (Swapna Dhavale 2017)

Fig. 1.1c shows a typical layout of a weaver's dwelling. (Graphic credit: Swapna Dhavale 2017)

The Gaothan area of Paithan consists of various ‘Puras’ and ‘Alis’, i.e. neighbourhoods and streets. They were distinct in physical character, function, community and their location with respect to the town centre.

Each of the neighbourhoods was meant for a specific community. Neighbourhoods such as Saliwada and Mominpura are where all the weavers’ families have been living. The houses here are smaller in size and the streets narrower as compared to the Sahukar settlement. The Sahukars, Joshis and Mahajans occupied the central area within Paithan due to their wealth and influence in the town. Here the plots were bigger, Wadas are grand and the streets are much wider as compared to Saliwada and Mominpura. Rangar Hatti is an area where all the dyeing works were carried out. This process required water and drainage facility. Thus, Rangar Hatti can be sited close to the river bank. Today, the infrastructure in these neighbourhoods is poor and the living conditions unhygienic. The width of the streets, plot sizes, architectural style of the dwellings when viewed in totality give a distinct character to each of these settlements.

Can revival of Paithan's heritage spur the process of urban development?

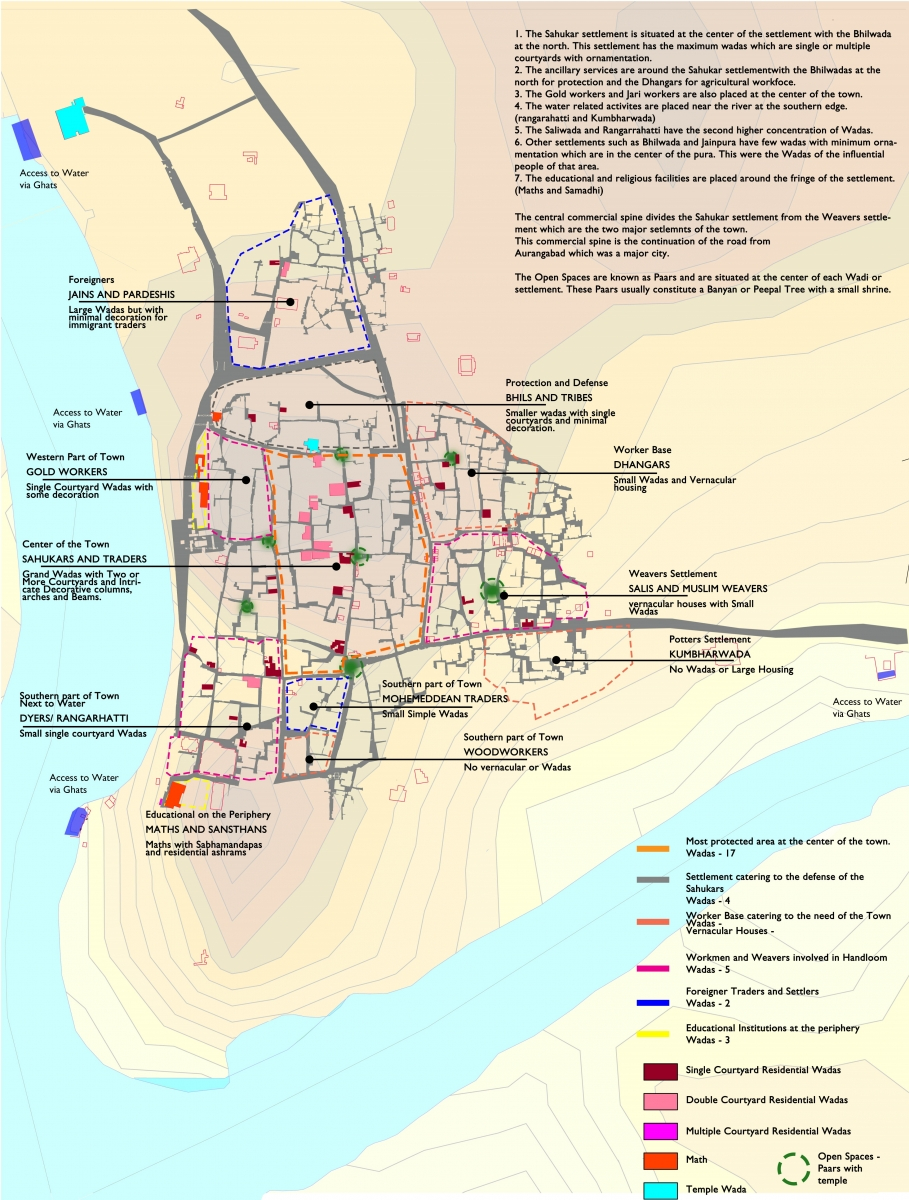

Fig.1.1d shows the urban form of present day Paithan. Various landmarks, mostly heritage can be seen scattered throughout the town. These include Wadas, Hindu and Jain temples, Maths etc. There are public places such as the Nath Mandir, Nag ghat, Ganesh Ghat, Kalikeshwar ghat, Sant Dnyaneshwar Udyan and many more. Many of the Wadas are under private ownership. Some of them are well maintained whereas some are in a sorry state. The Ladu Savkar wada which is protected by the ASI is one of the hidden gems within the town. (Graphic credit: Belapurkar, 2016)

According to the ASI, present-day Paithan itself stands on an archaeological mound which rises like a crescendo. Paithan and the area contiguous to it was inhabited in the Lower Palaeolithic, Middle Palaeolithic, Chalcolithic, Early Historical and Medieval times.

These places have been neglected due to a lack of administrative support and incentives for private owners as well as a lack of awareness and knowledge of the potential value of the heritage. Community awareness and initiatives can prove helpful in getting some much-required attention from the government bodies.

Paithani is so far the biggest attraction for tourists that come to Aurangabad, Ajanta and Ellora. Many Paithani selling centres have been set up in the city of Aurangabad itself. However, many are interested in the manufacturing of Paithani sarees as the handloom weaving process fascinates many tourists. Paithani weaving was once considered to be prestigious work in Paithan. It was associated with the royals and the affluent community. Today however, the weavers live in poor physical conditions. The Saliwada, a neighbourhood in Paithan where most weavers stay today portrays a sad picture of the dying art of Paithani weaving. Narrow lanes, poor quality housing, lack of infrastructure and basic hygiene characterises most of Saliwada and Mominpura. One would imagine Paithan’s main street to be lined with grand showrooms of the royal fabric. However, the main street does not boast of its heritage to any considerable degree.

All of these places within Paithan have strong potential for upliftment and thus to catalyse the process of urban development in Paithan. Due to their unique architectural style, use of material and aesthetics, and vernacular technologies, these places can become important tourist attractions.

Conclusion

There lies great potential in the town's cultural heritage to spur the process of urban development. Such efforts will help in building a unique urban identity for Paithan and its residents. This approach can not only help in historical conservation but can also create a better future for the people of Paithan. Broader community participation and involvement can lead to their well-being and security. Such an approach can help small towns cope with rapid urbanisation in surrounding areas and also achieve sustainable growth in subsequent years.

References

Belapurkar, R. 2016. Conserving the Historic Core of Paithan. Delhi: SPA, Delhi.

Dhavale, Swapna L. A. 2017. Regeneration of Ancient settlements and Cultural Industries: A Case Study of Paithan, Maharashtra, India . International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology, 105–11.

Fukukawa, P.P. 2006. 'Urban Regeneration of Historic Towns: Regeneration Strategies for Pauni. The Sustainable City IV: Urban Regeneration and Sustainability, 209–18.

Morwanchikar, R. 1984. The City of Saints: Paithan through the Ages. Aurangabad.