India is well known since ancient times for its handloom and cloth weaving industry. One of the major trade items in the Indo-Roman trade in the 2nd century CE was woven cloth, especially muslin, a cloth that can be dyed and embroidered, originating from Paithan. Caves in the region, from 1st century BCE to the 3rd Century CE, display inscriptions which detail the weaving industry of this era (Ministry of Textiles, GoI, 2008). Cotton and silks woven in India were one of the principal trade items until the 20th century CE, with brocades, fine cotton and linen being exported along with spices and other items. The Paithani, originating from Paithan, is one such handloom treasure purely woven in silk and zari (thread made of gold or silver).

Trade records from the 2nd century BCE maintain mentions of the silks and cotton of Pratishthana (Paithan) being exchanged for Roman wines and olive oil. Paithan has thus been a flourishing trade and textile town since the 2nd century BCE, however the craft of the Paithani really flourished in the 17th century and further reached its zenith in the early 19th century before witnessing a slow decline over time till it was revived in the 1960s and 1970s.

Crafts and other arts in India follow a specific pattern of transfer of knowledge from generation to generation. The art of weaving the Paithani follows a similar pattern with the art staying within the family. A master weaver would have apprentices from his family and total devotion to the craft was necessary with the tools of the trade being considered as a manifestation of god. Guilds of weavers were established for managing and ensuring creative competition and guaranteeing employment.

Today’s Paithani weavers are no longer from the original weaving families of Paithan and are specially trained in a Government of Maharashtra initiative workshop. Several private traders have established workshops as well with weavers from different places, especially southern India. The ancillary activities of weaving, such as zari making, dyeing or silk preparation, have all but disappeared from Paithan.

The Paithani, a pure silk saree with a zari of gold and silver traces its origin to the brocades of the Yadavas which were sourced from Paithan. Several descriptions of these brocades are traced including Ganga varni (in the shades of the Ganga), Bora jail (brocades with sprigs of flowers) and Malganthi, a textured fabric popular in the Yadava Empire.

The traditional Paithani saree is manufactured by hand in pure silk and dyed in traditional colours. Silk was originally sourced from Bangalore or Mysore and zari was sourced from various places in Gujarat, especially Surat. The preparation of silk and zari, dyeing and weaving, was all carried out in Paithan with its traders establishing guilds for the weaving of sarees. This range of ancillary activities also influenced the urban form of Paithan.

Components of a Paithani

A typical saree consists of a set of components such as the body, decorative edge (padar) and borders (zari kath). The Paithani is identified by its characteristic kath and padar which have typical motifs. These motifs are an important part of identifying the Paithani. Several types and variations of these motifs exist.

The components of the Paithani are:

The body (saree cha aanga) – The plain or decorated fabric which is the major component of the saree and woven in silk with small buttis. The buttis maybe of varying designs. The total length of the saree may be ‘sahavari’ or ‘nauvari’ with a var being equivalent to a yard of fabric. The typical Paithani is hence either six yards or nine yards in length and the width including the zar is one panna or 44 inches.

The edge (kath) – The border of the saree is in zari to add stiffness to the fabric and protect its edges from wear and tear. This is known as the kath. The kath is intricately decorated with traditional motifs and varies in thickness from two inches to 12 inches based on the skill of the weaver and design chosen for the saree. The kath is along both edges of the body of the saree and is designed symmetrically. It terminates into the padar and uses similar designs, motifs and colours.

The pallu (padar) – The Paithani padar has its own unique design. It generally consists of motifs of peacocks, flowers and leaves. The padar is generally about 24 to 36 inches of intricately woven zariwork at one end of the saree and hangs free over the left shoulder once the saree is draped.

Figure 1. Components of a Paithani saree

The total weight of a finished Paithani varies from 900 gm to 1500 gm depending on the quality of silk and zari used as well as width, quality and work required on the kath and padar.

Raw materials of the Paithani

The Paithani consists of two simple raw materials— mulberry silk historically and presently sourced from Bengaluru and Mysore, and zari, sourced from Surat, Gujarat.

Mulberry Silk

The silk was historically sourced from Mysore and Bengaluru. Mulberry silk was preferred for weaving. The undyed and unsorted silk was imported to Paithan and later dyed with organic dyes at the dyers' settlement to the south of Paithan. Today, the silk is generally pre-dyed with chemical dyes and obtained in two varieties. The warp (tana) is pre-stretched and is bought with pre-counted threads and in the length required for two sarees. The weft (bana) is brought as single filaments of silk and twirled together four or five times depending on the thickness of silk cloth to be woven before starting the weaving process. Silk is obtained in kilograms with mulberry silk costing around Rs. 3000 to Rs. 4000 per kilo. Each saree requires about 700 to 800 grams of silk thread for both tana and bana considering loss during weaving. Silk is tested for quality and authenticity by burning a length of silk. The silk thread after burning should smell like burnt hair and crumple into a ball which breaks easily after touching.

Figure 2. Undyed mulberry silk yarn. Source: www.indiamart.com/karmaenterprisesrajkot/Dinesh Bhai Patolawala Shop.

Zari

These days the zari is obtained from Surat. Zari is available in two types, copper zari which is a cotton thread twirled with copper wire and wrapped in gold foil, and silver zari, which is a silver wire with cotton thread coated with gold foil. The copper zari is cheaper and easier to weave and hence preferred over the silver zari. The market rate of zari varies everyday with copper zari costing around Rs. 2000 to Rs. 4000 per kilo based on the percentage of gold used, and silver zari costing Rs. 5000 to Rs. 6000 per kilo; each saree requires arounf 100 to 250 grams of zari.

Silver zari was traditionally used twirled with saffron or yellow cotton thread. The silver used was often mixed with zinc to impart strength and then coated with gold. Historically, embroidery of the kath-padar is done by a combination of gold and silver zari. The proportion of gold and silver is approximately one is to five to achieve the required strength of the zari. The ratio of silver to gold in the zari varies and the names of the saree evolved from these variations. As gold is measured in masa the names of the saree are described as chouda masi, bara masi and athara masi or eksheri, pavsheri or tinsheri, etc., denoting the amount of gold used. A shera is roughly hundred grams of zari.

The value of the Paithani is dependent on the amount of silver and gold zari used in it. Once the silk starts to tear, the saree is burnt down to extract the silver. However, this is not possible in sarees with copper zari. The test to check the presence of silver in the zari is to burn a single thread. In case of silver being present, the zari thread turns white and upon rubbing with hands, the silver wire is exposed. In case of copper being present, the remnants turn reddish black.

Figure 3. Silver-based zari used for weaving kath and padar

Dyes

Originally organic dyes were used for dyeing the silk. The dyes were obtained from various roots, flowers and metal oxides. The natural dyeing process is as follows: the unbleached silk is boiled in a solution of sodium carbonate or chuna (lime powder) or papad khar (sodium bicarbonate). This bleached silk is then soaked overnight in cold water and alum solution to act as a mordant. Mordant is required to ensure that the colour holds and does not bleed.The dye is added to boiling water and the bleached silk is soaked in the water for over an hour. This causes the dye to seep into the silk fibres and hold. This process is repeated multiple times till the required depth of colour is obtained.

Traditionally used colours such as deep yellow (pophali) is obtained from turmeric root and light yellow obtained from marigold flower petals. Deep yellow and orange colour is obtained from papad khar (sodium bicarbonate) and kapila (mallotus philippensis) powder. Kachi hirva or bottle green is from leaves of the gulmohar. Saffron is mixed with turmeric and the noni plant to obtain a deep mango yellow colour with alum as a mordant. Lavender and shades of blue are obtained by combining indigo with various other dyes such as red and black. Deep reds and magenta colours (falsa) are obtained by using Acacia arbica and Arabica catechu tree parts.

Plants used for obtaining dyes, which are commonly found in the Marathwada region are listed below. Various parts of the plants are used to obtain dyes. These names have been verified through research as well as through traditional knowledge bases of the weavers (Sujata Saxena 2014; Bhute 2012).

Table 1: List of plants used for organic dyes

|

Sl. No. |

Common Name |

Scientific Name |

Part Used |

Colour Obtained |

|

1 |

Phanas |

Atrocarpus heterophyllus |

Bark |

Yellow |

|

2 |

Gulmohar |

Delonix Regia |

Flower |

Olive Green |

|

3 |

Sagwan |

Tectona Grandis |

Leaves |

Yellow |

|

4 |

Babool |

Acacia nilotica |

Leaves, Bark |

Yellow and Brown |

|

5 |

Kamod/ Nilofer |

Nymphaea alba |

Rhizomes |

Blue |

|

6 |

Awala |

Emblica officinalis |

Bark, Fruit |

Grey |

|

7 |

Boracha zhad |

Ziziphus mauritiana |

Leaf |

Pink |

|

8 |

Shevgyacha zhad |

Moringa pterygosperma |

Leaf |

Yellow |

|

9 |

Chinchecha zhad |

Tamarindus indica |

Leaves, Seeds |

Brown |

|

10 |

Red Sandalwood |

Pterocarpus santalinus |

Wood |

Red |

|

11 |

Kardai cha Phool |

Carthamus tinctorius |

Flower |

Orange-red |

|

12 |

Halad |

Curcuma longa |

Rhizome |

Yellow |

|

13 |

Neel |

Indigofera tinctoria |

Leaf |

Blue/ Indigo |

|

14 |

Mehendi |

Lawsonia inermis |

Leaf |

Red |

|

15 |

Amba |

Mangifera indica |

Bark and Fruit |

Yellow |

|

16 |

Bakul |

Mimusops elengi |

Bark |

Brown |

|

17 |

Parijat |

Nyctanthes arbor-tristis |

Flower |

Bright orange |

|

18 |

Jhendu |

Tagetes erecta |

Flower |

Yellow |

|

19 |

Ala |

Zingiber officinale |

Rhizome |

Brown |

|

20 |

Jhambul |

Syzygium cumini |

Fruit |

Purple/black |

|

21 |

Kusumb |

Schleichera oleosa |

Fruit |

Red |

Some of the Paithani colours evolved through these organic dyes are: jambhuli (purple), morpankhi (peacock blue), neelambar (bright blue), motiya (peach), falsa (magenta), kusumbi (purple-red), kanchi hirva (bottle green), pasila (red-green), gujri (grey), mirani (deep red), banosi/dalimbi (deep red), gangavarni (indigo blue), chanderi (silver grey), soneri (golden yellow) as well as typical colours such as lal (red), pivla (yellow), shendri (saffron) (Prerna 2012).

In the present scenario, the dyes used are chemical dyes which give a vast range of colour options. The silk is pre-dyed and obtained from Bangalore Silk Board. Orders are given for required colours. The avaibility of chemical dyes has enabled a larger range of colours and shades.

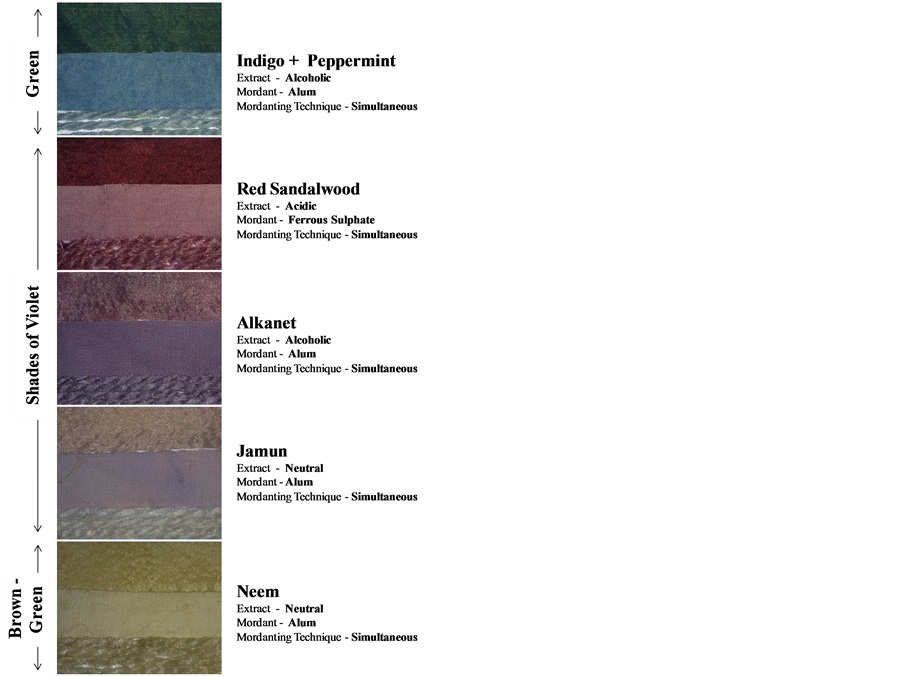

The range of colours obtained by combining various mordant and natural dyes is given below (Arora 2017).

Figure 4. Range of dyes in silk

Figure 5. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 6. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 7. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 8. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Preparation of weaving

The preparation for weaving the Paithani saree itself takes about four to five days, from preparation of the tana and the bana to preparing the loom.

Figure 9. Stretching the tana

j

The tana (warp) is first prepared by stretching and separating the silk threads. It is stretched multiple times by wrapping around a spindle to smoothen out kinks and detangle the thread.

Figure 10. Attaching to the dhol

It is then wrapped around the drum of the loom which is known as the dhol. It is ensured that the tana is tightly wrapped around the dhol to maintain tension. Loosening of the tana causes unequal weaving and warping of the saree.

Figure 11. Attaching to the ata

A beam called the ata is then attached to the rear of the loom and the tana sorted into bundles of ninety threads. The ata has sixteen reels spaced evenly on it. The tana has seventeen and a half bundles of ninety threads.

Figure 12. Jodni by hand

The threads in the bundles are then joined individually by twisting through the heddles. This process is called jodni. It is a time-consuming process and takes 12 to 18 hours to finish. The process involves taking each thread and joining them alternatively over and under a bar of the loom.

Figure 13. Thape and Phalka

Figure 14. Preparing the bana

The bana (weft) is prepared on the thape, which are a set of three stone pedestals. The thape are three wooden rods on stone bases, one of which has grooves to hold the phalka (a large cage made of string and bamboo). The ready bana is then shifted to the tansal. The weft is generally three or five ply and is prepared by winding on the thape multiple times.

Figure 15. Sorting on the yantra

After creating the three-ply weft on the tansal, it is stretched on the yantra (spinning wheel), and wound around kandya (bobbins). The kandya are usually made of pine wood and tapered at both the ends.

The loom is generally made of teak wood as it is more durable and less prone to warping or decay. However, today, due to limitations, only the warp beam, cloth roller and beater are made of teak wood as these need to be durable to prevent any defect in the cloth.

The parts of the loom are:

Ata - back beam with seventeen divisions

Dhol - warping beam/ warp roller

Hatya - beater

Dhota - shuttle

Pavdya - treadles

Phani - reed heddles

Tulai - cloth roller

Kandya - bobbin

After the preparation of the warp and the weft, the saree is ready to be started.

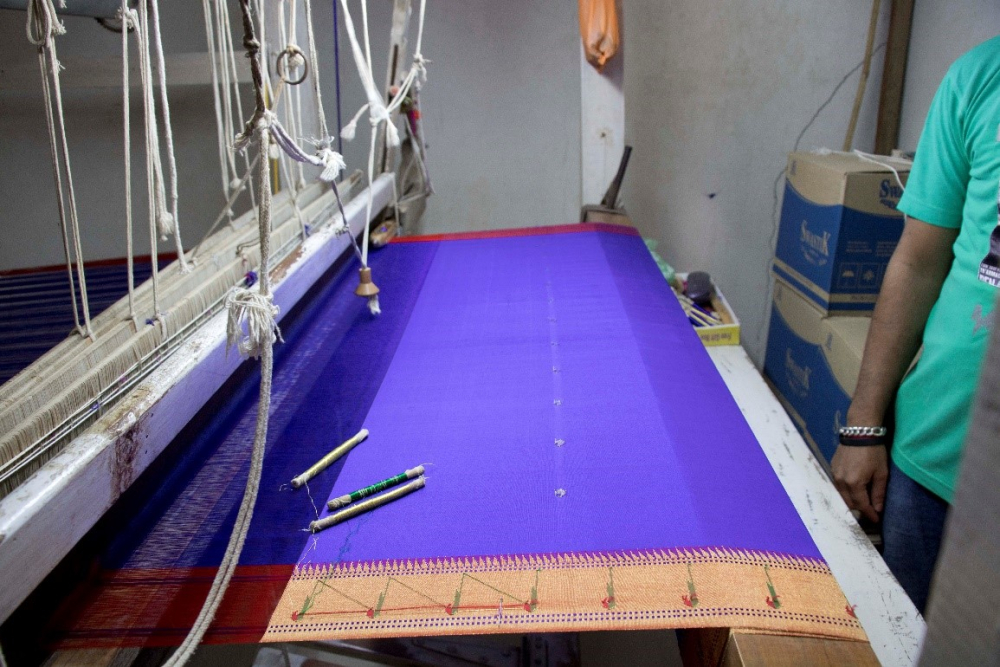

The weaving process

The first element of the saree to be woven is the pallu or the padar. The padar is woven in zari weft over a silk warp. The zari was traditionally silver with a wash of gold but today has a base of bronze. The padar contains the distinctive motifs of the Paithani such as the mor, bangdi mor, kamal, asawali and akruti. The padar is one of the most intricate and time-consuming parts of the Paithani to be woven and takes anywhere from two weeks to two months to weave depending on its length, level of detail and intricacies of the motifs.

Figure 16 Weaving the padar

The motifs are in silk bana over a base of gold zari and while weaving, the weaver counts the number of threads by feeling them with his fingertips. This is a skill acquired over years of practice. The simplest motifs are the buttis and the tota while the most difficult to weave is the bangdi mor. The padar will generally have a central element such as the kunda mor (peacock on a vase), phulzhad (tree with flowers or peacocks), padmakamal (lotuses) or bangdi mor (peacocks in a circle). These central elements will be banded in long narrow borders of tota maina, vel, koiri motifs or bands of vertical dashed lines to enhance the padar.

Figure 17. Implements for weaving

The body of the Paithani is the next part. The body is defined by a border on its edge. If the body of the saree is plain, a throw shuttle is used, however, if buttis are present, then each butti is handwoven in zari.

Figure 18. Weaving the body of the saree

The saree might have a total of 200 to 300 buttis woven. A complete Paithani will have all buttis handwoven which is a slow and time-consuming process. The buttis also come in different motifs such as peacocks, flowers, petals, paisa and parinda.

The designs of the Paithani are preset and each designer adds elements as he weaves. The weaver can make designs or use typical traditional patterns. However, the count of threads while weaving remains the same always. In a day’s work, the weaver weaves two inches of padar and five to six inches of body on an average. Each saree, hence takes a minimum of three months to weave if it’s completely handwoven. A saree with a thick 18-inch border and 36-inch padar will take a year to weave. While weaving, the tana is checked for equal tension by feeling it with fingers. If found to be unequal, the relevant reel on the ata is tightened and the tana is then wet with water to increase tension. Unequal tana will cause snarls in the fabric of the saree. After every 3 to 4 inches, the zari is polished with a mixture of gum and water to stiffen and preserve it. This polishes the zari, seals any loose threads and stiffens the border. Sticky substances such as jaggery, methi or gum is used in the mixture. These substances do not cause any deposits or marks in the zari. The zari used is either of copper with gold or silver thread coated with gold. The tana is of silk, however the bana is of zari. This causes the zari border to have a distinctive colour. If the zari is of silver, the zari border and padar will have a reddish tinge, however, if the zari is bronze based, the zari will be a bright golden yellow in colour. The saree is carefully unwrapped from the cloth roller (tulai), cleaned and folded.

The colours of the saree are obtained by combining different colours of tana and bana. This increases the spectrum of colours of the Paithani. For example, a red tana and a blue bana will give a shade of purple, while a tana of black silk and a bana of green will give a shade of dark green Paithani. Certain shades of colours will give a dhuup chaon (dual tone) effect to the saree with changing colour. This combination enables creating a variety of colours of Paithanis based on a limited number of colours in the tana and bana. If the saree is of a single colour warp and weft it is known as daryai. If the saree is of two different coloured warp and wefts it is known as dhoop chaon. If multiple colours are used in warp and weft it is known as par-i-taus, and if chequered it is known as charkhani (Morwanchikar 1993).

Vernacular terms of weaving

The weavers have a vernacular name for every process and part of weaving the Paithani, however, due to decrease in the weavers’ community, lessening of awareness of the techniques of weaving and lack of written documentation, some of the terms are lost today. Even then, the most commonly used terms are mentioned below. They include terms for boiling of silk, preparing the tana and bana, and nomenclature of the parts of the loom:

Ukalap - sorting silk thread based on quality and thickness

Ukhar - bleaching of silk in boiling solution of sodium carbonate or papar khar or chuna

Tana - warp

Bana - weft

Phalka - cage of bamboo and string

Asari - conical reel

Yantra - spinning wheel

Khandki - bobbins made of reed

Sacha - bobbin frame

Rahat/dhota - throwing spool

Turai - cloth beam

Hatya – reed frame

Phani - comb for weaving

Ata - warping beam

The weavers of Paithan

Historically, Paithan has always been centered around the weaving industry. Every household in Paithan was linked with weaving and ancillary activities such as dyeing the silk, winding the zari or even selling the silk sarees. A majority of the population of Paithan was involved in weaving the sarees with the Koshtis, Salis and the Momin communities consisting of the larger part of the demography. Today, only a few weaving families remain involved in the traditional occupation of weaving. A few such distinguished families are also recipients of the National Award for weaving.

Figure 19. A traditional weaver (Sh. Dhalkari)

Figure 20. The finished saree

Learning the art of Paithani weaving was a long and arduous process with the apprentice being introduced to the task at the young age of twelve or fourteen. The first task given to the apprentice was to sort the silk thread and prepare the bobbins. As he grew adept in handling the thread, he was taught the art of weaving a plain silk cloth by using a shuttle and taught how to operate the loom. When the master weaver felt that the apprentice was ready to learn the motifs, he was given the task of weaving simpler motifs and buttis such as the tota and the sunflower. The apprentice had to practice multiple times till he could weave perfect motifs. This could take a fast learner six to eight months to achieve. Then he slowly graduated on to weaving the body for the saree with its border. More complicated motifs such as the peacock and the lotus were then introduced to him. The last motif generally taught was the bangdi mor as it is the most complex. An apprentice would continue in his tutelage for two to four years before he could be given an entire saree to be woven.

The structure of the weavers is such that a master weaver generally has four to eight looms in his house and has an equal number of apprentices involved at varying stages of capability. Each master weaver in turn was patronised by a family of sahukars who took care of the orders. They provided materials, the investment required and ensured that the Paithanis are marketed and sold in other cities. The weavers from Paithan were often invited under royal patronage to settle in various places. The king of Gujarat, Siddharaja Solanki, invaded Paithan and took the craft to Gujarat in the 12th century CE by extending invitations to the weavers to settle in Yeola and parts of Gujarat.

Paithani received royal patronage under Aurangzeb, the Marathas and Peshwas, as well as the Nizams. The high cost of materials as well as the time and effort required for weaving and the high selling price caused its decline in the 20th century. Today, three to four families remain who can state an unbroken line of weaving back to four or five generations. The Maharashtra government rejuvenated the art by training women in the Paithani Kala Kendra. Today some 200 women are trained in this traditional art of weaving.

Not just the weavers but a variety of different communities are involved in the creation of the saree:

1. Dyeing - Bhavsar community

2. Gold and silver work - Sonar community

3. Zari - Pavtekar and Chapade communities

4. Separating (Winding silk from dyed bundle onto loom) - Women from Sali, Koshti and Momin communities

5. Weaving - Sali, Koshti and Momin communities

Paithani weaving has influenced the town and settlement of Paithan with the various communities living together and forming distinct smaller settlement areas such as Saliwada or Rangarrahatti. The names of the suburbs such as Rangarhatti, Chapade-gali, Taru-gali, Pavata, are more than suggestive of this. The area of ‘Rangarhatti’ is named after the inhabitants who did the bleaching and dyeing work. The area of Taru-gali, after the taru who transferred gold-silver bars into threads. Jar-galli was a place where the gold threads were wound with silk. There is yet another place called Pavata where big machines for making gold and silver strips were fixed (Ministry of Textiles GoI 2008).

The motifs used in Paithani also influenced the architecture of the Wadas with similar motifs being used in brackets and arches. Houses of the traders or sahukars, for example, display special rooms used for storage of raw materials and finished silk cloth. Such rooms are wooden enclosures above the entrance with proper ventilation and moisture controlling measures.

Market scenario

Today, the market is flooded with fake power loom Paithanis. These are easier and faster to manufacture. Each Paithani takes five to six hours to manufacture. The designs are fed into a computer and the power loom has the capability to duplicate designs. These Paithanis, due to their ease of manufacture, are priced competitively and range from Rs. 2000 to Rs. 10,000. Another cheaper Paithani is the Yeola Paithani which is done on a Kadhiyal loom and is also faster to weave. The original Paithan Paithani is a GI product and hence is protected under the The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act, 1999 and the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Rules, 2002 (Mathew 2009). However, due to lack of awareness of the defining points of a Paithani, customers today are not aware of the finer points of the Paithani and hence are easily duped by shops. A quick customer survey showed that in traditional saree shops that are patronised by families for generations, a power loom Paithani is often sold at the cost of a handloom Paithani as the customers are not aware of the original product and trust the shop owner. Even in Paithan, several shops can be found which promise a Paithani at prices as low as Rs. 500 to Rs. 2000 (Kasat, 2017).

However, a real Paithani has several distinctive signs to identify it as a handloom Paithani from Paithan, such as observing the motifs closely, examining the cloth and zari, looking for faults and warps in the saree, etc. No two Paithani sarees are exactly the same as each saree is woven individually and has different and unique motifs. However, power loom sarees tend to be similar and cater to a larger set in terms of motifs, colours and arrangements.

The issues thus faced by handloom sarees are that since the price is very high, there is a lesser demand for authentic handloom Paithanis. The demand for sarees too has reduced as women today prefer having something easy to manage and maintain.

The weaver’s community is shrinking as well and it is harder to find traditional weavers or weavers having complete knowledge of the techniques. As the process of weaving is slow and tedious, the younger community does not prefer doing the traditional jobs and are migrating towards the cities. This has caused loss of traditional knowledge systems of weaving. Certain institutions and the Textile Ministry are, however, taking steps to counter loss of weavers and hold training programmes for new weavers. The Mahratta Paithani Center trains women from the Sali, Koshti and Momin communities in preparing the loom and weaving. This has caused a shift in the demography of weavers in Paithan from a male-centric occupation to a female-centric one.

The Paithani Weavers Association has also diversified their range of products into throws, covers, fabric pouches and salwar suits to adjust to the changing markets. While the Paithani saree remains a choice for brides across Maharashtra, the demand for other products has also risen. However, there is a need for professional designers to create a market for the fabric of the Paithani and create products to suit the current trends while retaining the traditional techniques, motifs and colours as well as reviving the organic methods of dyeing and preparing the silk.

There is also a need to create awareness of the Paithan sarees amongst the customers and the shop owners. Awareness of the GI, Silkmark and Handloom Mark must also be increased among the general public and the customer must ensure that the Paithani they are buying contains all three tags.

References and Further Reading

Arora, J.A. 2017. Rainbow of Natural Dyes on Textiles Using Plants Extracts: Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Processes. Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 35–47. China.

Bhute, A. 2012. Plant Based Dyes and Mordants: a Review. Thane: Scholar Research Library.

Class, T. o. 2006. www.touchofclass.co.in/Motifs. Retrieved from www.touchofclass.co.in: http://www.touchofclass.co.in/Motifs.html (viewed on February 22, 2018)

Hingmire, P. G. 2010. Application for Registering PAITHANI Saree and Fabrics as GI. Pune: Pratishthan Paithani Weaver's Association.

Humbe, V.R. 2013. Consumer Behavior Approach towards Handloom Industries of Maharashtra State with Special reference to Paithani, Asia Pacific Research Conference.

Katare, Veenu. 2016. ‘Symbolic Motifs in Traditional Indian Textiles and Embroideries’, IJRESS Vol. 6 Issue 3.

Mathew, D. S. 2009. The Protection of Geographical Indication in India – Case Study on ‘Darjeeling Tea’. Pune: Pratishthan Paithani Weaver's Association.

Ministry of Textiles, GoI. 2008. Study and documentation of Paithani Sarees & Dress Materials. Mumbai: Ministry of Textiles.

Morwanchikar, R. S. 1985. Paithan through the Ages: City of Saints. Delhi: Ajanta Books

———. 1985. Woodwork of Western India. Delhi: D P Taneja.

——— 1993. Paithani: A romance in brocades. Pune: Bharatiya Book Corporation.

MSSIDC. (n.d.). History of Paithani. Mumbai: MSSIDC.

Prerna. 2012. http://myblog-prerna.blogspot.in/2012/03/paithani-textiles.html. March 13. Retrieved from blogspot.com: http://myblog-prerna.blogspot.in/2012/03/paithani-textiles.html

Ray, H. 1989. Early Historical Urbanization: The Case of the Western Deccan. World Archaeology, Vol. 19, 94 - 104.

Saxena, A. R., Sujata. 2014. Natural Dyes:Sources, Chemistry, Application and Sustainibility Issues. Mumbai: Springer.

Sharma, S.R. 1944, Maratha History Re-examined (1295-1707), Fergusson College.