It is believed that Buddha Purnima marks the full-moon summer night that saw the birth of a boy who would go on to teach the world about finding happiness by understanding the true nature of life. Central to Buddhist thought are ruminations on suffering brought on by sickness, old age, disappointment and death. The Buddha believed that everyone was capable of enlightenment, and yet his reluctance to include women in the sangha is well-known. We look at some of these themes through the Therigatha, a collection of poems by Buddhist nuns written over a period of over 300 years. (Photo Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art [Public domain])

Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future,

concentrate the mind on the present moment.

—Gautama Buddha

A spiritual quest to understand suffering—ageing, sickness and death—marked the beginning of a philosophical tradition that continues to influence people more than 2500 years later. Siddhartha, who the world would go on to know as Gautama Buddha, was born on a full-moon night. His astrological charts predicted fame—either by becoming a great king or a great monk. His worried father, the head of the Shakya clan, filled his life with luxuries and merriment, hoping to keep him away from despair and darkness that could trigger a turn to asceticism. That we today celebrate the full-moon night of the summer month of Baisakh as Buddha Purnima, indicates the sad defeat of a father against the destiny his son decided for himself.

Three instances of witnessing sickness, old age and death spurred Siddhartha to join an established philosophical tradition in the ancient Indian sub-continent—to set out on personal journeys to seek answers to the only question that seemed to matter: the ultimate truth of reality. For Siddhartha, though, the search was always through the prism of the nature of suffering, the seeming inevitability of coming across sickness, misery and death in one’s life.

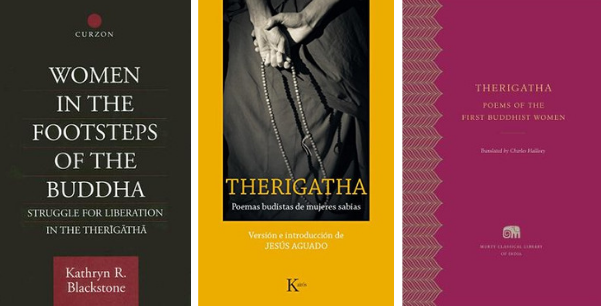

It is said that the poems in Therigatha were passed down orally in Magadhi for a few hundred years, before being compiled together in Pali in 1st century BCE (Courtesy: Goodreads)

The Buddhist canon contains many references to the ways in which the Buddha, or those around him, exemplified the Buddhist approach to suffering. Some of the best-known stories involve women in various roles, and come from what is believed to be a book written by the first Buddhist women.

Also Read | Guru Padmasambhava: Buddha of The Vajrayana

The Therigatha (literally, ‘verses of old women’) is a collection of 73 poems written by Buddhist nuns over a period of 300 years. ‘Theri’ refers to elderly women, though Susan Murcott argues that it refers to distinguished women (nuns) of wisdom and character, and not merely elderly nuns.[i] It is said that the poems were passed down orally in Magadhi for a few hundred years, before being compiled in Pali in 1st century BCE.

The poems are renditions of stories, situations and emotions that seem remarkably extant. Depression, loss, marriage, motherhood, betrayal, menopause and death—all feature as causes of suffering, which are then overcome through Buddhist teachings.

Also See | Buddhist Caves of Ellora

One of the first poems in the book is by the first Buddhist nun, Pajapati Gotami. After Siddhartha’s birth mother, Maya, passed away shortly after giving birth, it was her sister, Pajapati, who raised him. Years later, a much older Pajapati who, by then, had no worldly obligations, fought her way into being accepted in the sangha (community of monks) as a nun. With her were hundreds of women who had lost their families—first in wars, and then to Buddhism, when the men renounced war and became monks. Her reluctant foster son allowed her to practice the Buddhist dharma as a nun, provided that Pajapati and her band of women accepted eight conditions that firmly placed the nuns below the rank of monks.

It is interesting to note that while the Buddha agreed that women were as worthy as men when it came to achieving the ultimate state of enlightenment, yet, perhaps given the societal realities of the time, he was clearly uncomfortable with the idea of nuns being given authority equal to that of monks.

However, Pajapati was a formidable woman and with time, questioned some of the conditions she had previously agreed to. At the heart of her challenge lay a deeply democratic and egalitarian impulse that seems surprisingly ‘modern’. The challenge, unfortunately for her, did not move the Tathagata (another name for the Buddha), and the inferior status accorded to women in the sangha continued.

One of the first poems in the book is by Siddhartha’s maternal aunt and the first Buddhist nun, Pajapati Gotami (Courtesy: MediaJet (A Photograph of a Very old Lithographic Painting drawn by Maligawage Sarlis Master of Ceylon, captured by the author sometime in 2009) [Public domain])

Later, Pajapati gained enlightenment, becoming the first Buddhist woman to do so. At the old age of 120, as she lay dying, she sent out a request to the Buddha—she wanted to see him before passing away.

Despite his own stipulation that under no circumstance was a monk to visit a nun—even if the nun was sick—Gautama Buddha couldn’t refuse this last request from Pajapati. And so, in her death, the first female dharma follower helped bring about some change—as the rule then stood altered. The story goes that just before her death, the Buddha requested her to perform miracles—to convince other men that women could indeed achieve nirvana.

Also Read | Jataka Tales: Karma, Life, Lessons and Stories of the Afterlife

In a verse in the Therigatha, Pajapati speaks of her sister Maya as being, in a way, responsible for suffering being removed from the lives of people:

Truly for the sake of many,

Maya bore Gotama.

She thrust away the mass of pain

Of those struck by sickness and death.[ii]

Another notable piece of writing comes from Kisa Gotami, Siddhartha’s cousin, who lost her sanity when her son died. She went from place to place, with her son’s dead body in her arms, pleading for him to be revived. Eventually, someone asked her to meet the Buddha. The Buddha greeted her with great kindness, and asked her to bring him one mustard seed from a house that had not seen death. Upon her doing so, he promised, he would bring her child back to life.

The Buddhist canon contains many references to the ways in which the Buddha or those around him exemplified the Buddhist approach to suffering (In pic: Mahapratiharya mural at the Ajanta Caves, Courtesy: Sahapedia.org)

However, Kisa was unable to find such a mustard seed, because there was no house that had not experienced death. Through this process, Kisa came to terms with the omnipresence of death; and understood that life and death are one cycle, and one cannot come without the other.

Also Read | Ajanta: The Hinayana-Mahayana Transition

Kisa finally buried her son, became a bhikkuni (female monastic), and joined the dharma. In the Therigatha, she says:

The arrow is out.

I have put my burden down.

What has to be done has been done.

Sister Kisagotami

With a free mind

Has said this.[iii]

Elsewhere, she says:

I have finished with the death of my child,

And men belong to that past.

I don’t grieve.

I don’t cry.

I’m not afraid of you, friend.[iv]

Everywhere

The love of pleasure is destroyed.

The great dark is torn apart

And Death,

You too are destroyed.[v]

The wisdom to understand suffering and gain mastery over it, and even more importantly, to lose the fear of it, is perhaps Gautama Buddha’s most enduring legacy.

This article was also published on Scroll.in.

[i] Susan Murcott, The First Buddhist Women: Translations and Commentary on the Therigatha (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1991).

[ii] Charles Hallisey, trans., Therigatha: Poems of the First Buddhist Women (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 103.

[iv] Referring to Mara, the ‘evil one’, in Buddhism

[v] From Samyutta Nikaya, the third division of the Sutta Pitaka, a collection of suttas, or discourses, attributed to the Buddha and some of his closest disciples. Susan Murcott, The First Buddhist Women: Translations and Commentary on the Therigatha (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1991).