Jataka Tales are part of Buddhist Theravada literature, which depict earlier incarnations of Gautama Buddha. In each of the fables, the Buddha demonstrates an aspect of non-violence (ahimsa) as he advances towards the perfection to be achieved in the birth as Siddhartha Gautama. These tales are a storehouse of information about life and society in ancient India [Fig. 1. Depiction of a Jataka Tale at Candi Mendut, central Java (Photo Source: Photo Dharma/Wikimedia Commons)]

Dated between 300 BCE and 400 CE, Jataka Tales are part of the canon of sacred Buddhist literature that features nearly 550 anecdotes and fables depicting earlier incarnations of Siddhartha Gautama, the future Buddha. Traditionally, the birth and death years of Siddhartha Gautama are considered to be 563 BCE and 483 BCE, respectively. In earlier incarnations, Buddha is sometimes an animal, sometimes a bird and sometimes a human. In each of the fables, the Buddha demonstrates an aspect of non-violence (ahimsa) as he advances towards the perfection to be achieved in the birth as Siddhartha Gautama. Even though, to a question from King Milinda on the existence of souls, the enlightened Buddha simply smiled, the transmigration of souls and the afterlife imaginaries associated with them in the Jataka tales are central to certain schools of Buddhism, especially Theravada Buddhism[1]. Regardless of whether one believes in the transmigration of souls or not, renowned Sri Lankan anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere thinks that the idea of ‘karma’ is closely associated with the afterlife and rebirth imaginaries. Obeyesekere in his famous book Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist and Greek Rebirth, finds the idea of Karma central to the ethical thinking of many world cultures. If in small-scale societies there exists a tendency for the deceased individual to reincarnate as a new-born member of the same kin group, in the case of large-scale literate civilisations, one's present birth tends to be a fruit of moral behaviour in the previous life. Obeyesekere argues that the central instance of this is the doctrine of Karma familiar to him not only from Sri Lankan Buddhism, but also from many religions across the world. In the South Asian context, the idea of Karma is common to the Vedic/Upanishadic Hindu background from which Buddhism emerged and to other reincarnation doctrines of the Jains, Avijikas and Balinese.

If at all there is an Indian way of thinking, if at all there is an Indian worldview that shapes our everyday life, one could easily term ‘Karma and the afterlife imaginaries’ as the central axis of our thinking. What is surprising would be the role of the Jataka Tales in establishing this central axis firmly in our minds. This has been possible in our culture because more than the philosophical and theological doctrines, the ideas and values of Indian spiritual heritage have been circulated and absorbed through rich storytelling traditions. Today, we may not know that the popular stories such as 'The Wise Judge Who Identified the True Mother', 'The Monkey and the Crocodile', 'The Turtle Who Could Not Stop Talking' and 'The Crab and the Crane' are originally from the Jataka Tales. Like tunes, tales travel across geographical regions and time zones to enliven perspectives and shape worldviews.

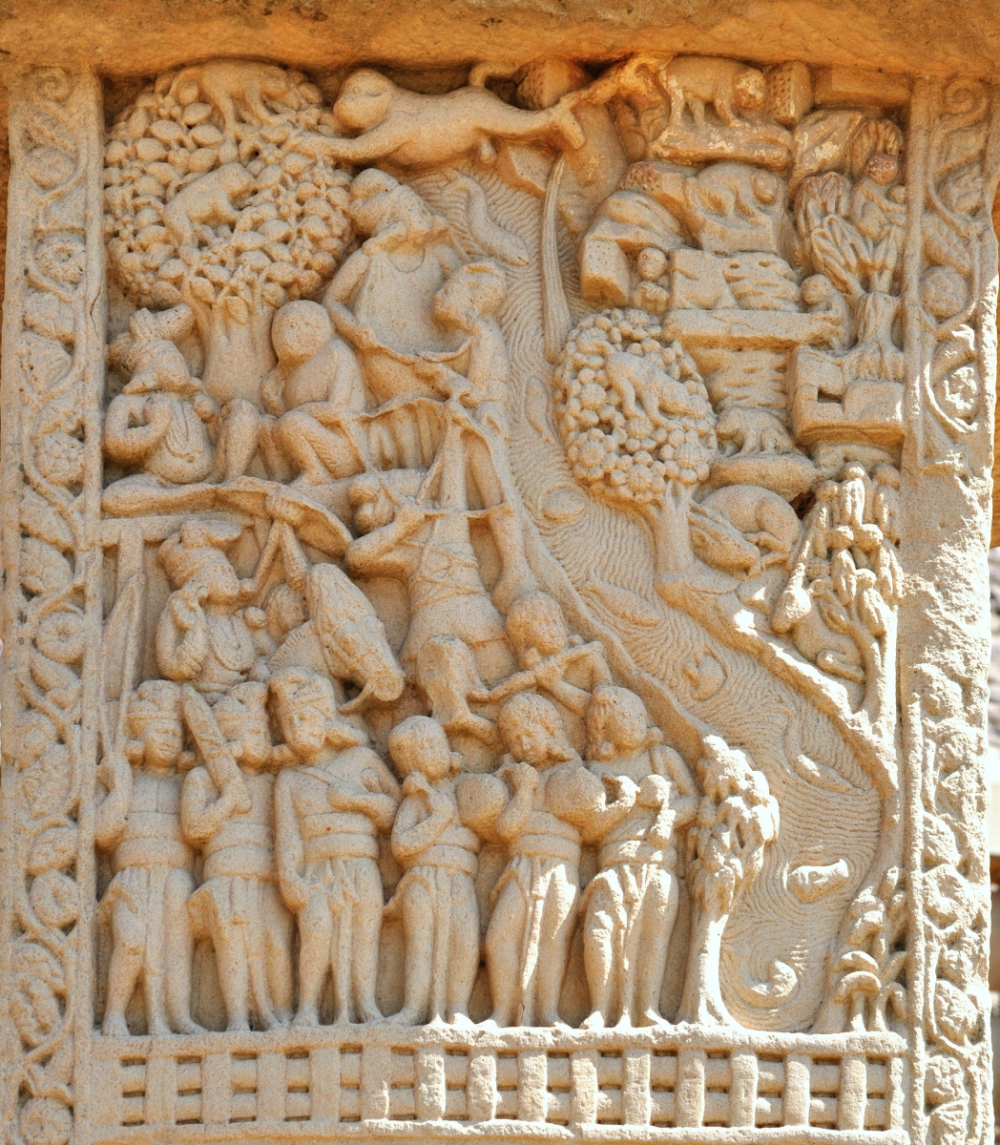

Fig. 2. Depiction of a Jataka Tale in an Amaravati Buddhist sculpture, on display at the Government Museum, Egmore, Chennai (Photo courtesy M.D. Muthukumaraswamy)

Though the settings for most of the Jataka Tales would be Benares (now Varanasi), the locations where the Jataka incidents occurred lay all over India. Many Buddhist stupas stand to signify incidents in the Jataka Tales. Among the episodes narrated, supreme sacrifice performed out of compassion by the evolving Buddha merits the establishment of a stupa. The Mankiala Stupa in present-day Pakistan stands testimony to an incarnation of the Buddha, Prince Sattva, who sacrificed himself to feed hungry baby tigers. At another site as King Sibi, he cuts his flesh to save a dove from a hawk. The Amaravati narrative sculptures housed in the Government Museum in Chennai and in the British Museum, London, depict many of the Jataka Tales and episodes from the Buddha’s life. What we see in these monuments and sculptures is a civilisation that remembers, honours and celebrates supreme sacrifices done not out of bravery but out of compassion towards the weakest of the weak and the poorest of the poor. For the Buddha incarnations, compassionate acts are spontaneous and they shape the evolution towards perfection. We also learn from the Jataka Tales that Karma and its scents (Vasanas) following us through several of our births are not all fatalistic but are formed by our actions. To act is to evolve.

Fig. 3. A 1st century BCE depiction of the Mahakapi Jataka in Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh. The tale revolves around Bodhisattva in a previous life as the king of 80,000 monkeys. When attacked by a king, the Bodhisattva helps the other monkeys to flee and travel across a stream by creating a bridgne with his own body (Photo Source: Biswarup Ganguly/Wikimedia Commons)

The first scholar who thoroughly examined the Jataka Tales, T.W. Rhys-Davids (1911) described the text as 'full of information on the daily habits and customs and beliefs of the people of India and on every variety of the numerous questions that arise as to their economic and social condition.' While the collection of Jataka Tales is indeed a storehouse of information about life and society in ancient India, the literary qualities of the tales went through constant refinement through centuries of retellings in the Theravada Buddhist monasteries, painted walls, aphorisms that circulated as proverbs and belief narratives surrounding the Buddhist stupas. The Jataka Tales are not just texts, but they are life forces that provided the tools for people to reflect on their everyday situations. That probably explains the existence of incomplete, crude and morally ambiguous fragments in the collection of Jataka Tales.

From the Pali canons through centuries of permeating many South Asian languages, Jataka Tales live many lives, continuously evolving their Karma and asserting their paths towards the perfection of storytelling. Framed as anecdotes narrated by the Buddha who connects the past event and the characters in the stories to the present, Jataka Tales demand a Buddha in their every retelling. Appropriately, in Theravada Buddhism, several of the long Jataka Tales such as The Twelve Sisters and Vessantara Jataka are performed as dance, theatre and celebratory events enabling masses to participate in the narration of Jataka Tales.

Fig. 4. The Mankiala Stupa in present-day Pakistan stands testimony to an incarnation Buddha, Prince Sattva, who sacrificed himself to feed hungry baby tigers (Photo Source: Khalid Mahmood/Wikimedia Commons)

To illustrate the diverse and changing nature of the genre of Jataka Tales, Naomi Appleton (author of Jataka Stories in Theravada Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisatta Path) tells us the story of Kimsukopama-Jataka (JA248). In the story, four princes ask their charioteer to show them the Kimsuka tree. He takes each of them to the tree in turn. He seats the eldest son in the chariot and takes him to the forest. Saying, ‘This is the Kiṃsuka,’ he showed him a tree, which at the time was just a trunk. The next son he showed the tree at the time when young foliage had sprouted, the next at its time of flowering, and the fourth at the time of fruit bearing. Later, the four brothers were sitting together and raised the question, ‘What sort of tree is the Kiṃsuka?’ One said ‘it is like a burnt pillar,’ the second, ‘it is like a banyan tree,’ the third, ‘it is like a piece of flesh’ and the fourth, ‘it is like an acacia tree.’ Perplexed at each other’s answers, they go to their father, the King of Varanasi (who is the Bodhisattva), to settle the matter. He replies with the first stanza of the Jataka:

'All have seen the Kimsuka; why now do you doubt?

Nobody asked the charioteer about all the conditions!'

Reading or hearing the Jataka tales always requires us to identify the charioteer.

Views expressed are personal.

[1] Theravada Buddhism is a school of Buddhism, the most ancient one that grew out of the Hinayana brach of Buddhism. Hinayana accords importance to rituals and festivities. It is widely followed in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.