‘Not just Shivaji. Address him as Shivaji Maharaj,’ said one of the artists from the play Janata Raja, of which I have been a part for over 15 years.

In the academic world, people are addressed by their names simply without any prefix or titles, unless necessary. This is practised, I speculate, to portray and study unbiased descriptions of historical events or figures.

However, Maharashtra, and especially the city of Pune, is in the grip of its past and the people of this land have a special pride about the days gone by. Past thrives in the memories of communities and individuals, in institutions and families, and seeps into performance traditions and poetry. The past, particularly the Maratha period, is so intricately interwoven into the fabric of the society, culture and politics of Maharashtra that to have a fair understanding of it requires the historian to venture into unconventional areas not traditionally treated as ‘sources’.

Theatrical plays are one of the sites through which history reaches out to the people in a way that is appealing to the audiences. Janata Raja, a three-hour play written and directed by Balwant Moreshar Purandare, also known as Shivshahir (Shivaji’s bard) Babasaheb Purandare, was first staged in 1985 in Pune on the grounds of Renuka Swaroop Girls High School. Since then, the play has staged thousands of shows across India and USA.

Unlike the other theatrical productions based on the historical figure of Shivaji, Janata Raja deserves special attention due to the grandeur of its staging. It becomes even more important to look at this play as it has been almost ritualistically performed in Maharashtra and other parts of the country since 1985. Having been a performer in this play since childhood, it has made a deep impression on me as a performer, individual and researcher.

The inception of the vision of this play goes back to 1974, when an exhibition called Shivsrushti was organised on the grounds of Shivaji Park in Bombay to commemorate the tricentenary anniversary of the coronation of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. (Fig. 1) The exhibition was curated in the palatial set of a fort, and important sites of Maratha history—such as the temple of Goddess Bhavani, Raigad and Sinhagad forts, and an effigy of an elephant adorned with jewels—were staged to display Maratha prowess. It displayed armoury, weaponry and antiquities from the Prince of Wales Museum (now called Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya). The main attraction was the Bhavani talwar, the sword which Shivaji had used during his reign.[1] Purandare was at the forefront in the organisation of this event. Leaders such as Yashwantrao Chavan and Balasaheb Thackeray also visited the exhibition.

The decade of 1960s was a time of great political upheaval in the state of Maharashtra, and Shivshruti was true to the concerns of the time. Maharashtra and Gujarat were declared separate states, independent from the Bombay Presidency in 1960. The Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti generated a discourse for ‘Maharashtrian pride’ and ‘superiority of Marathi culture’.[2] The regional party Shiv Sena (literally, army of Shivaji) was founded by Balasaheb Thackeray in 1966, with the agenda to reserve jobs for Marathi-speakers and Maharashtra natives in Mumbai.

Purandare, who had by then become popular due to the publication of his books and lectures on Shivaji, also decided to include the coronation ceremony in the exhibition.[3] The 22-minute skit of the coronation ceremony was written by him and directed by Damu Kenkre. This skit, too, like the play Janata Raja, was recorded, and 100 artists participated in it. (Fig. 2) With the overwhelming public response to the skit, Purandare then envisioned and wrote the full-fledged play on the historical character of Shivaji, which was eventually staged in 1985. An event to commemorate 300 years of Shivaji’s coronation and to revive the historical figure of Shivaji in public memory was to take deeper roots due to its repeated staging.

However, the reasons for the play’s effect and popularity are much more than that. Undeniably, Shivaji holds a special place in the public imagination of Maharashtra but credit must also be given to Purandare for basing the play in the poetics and the narrative of folk art forms of the state. The mahanatya (mega-play) was one of a kind, with its massive stage and about 250 actors.

Folk forms in Janata Raja

In Maharashtra, a hero is praised through a powada (a form of dramatised singing to laud a person). Powada is sung by the shahir, the main poet, combining verses and prose. He plays a drum called duff and is supported by the chorus, which stands with instruments in a semi-circle behind him. The powada is sung usually in a high pitch and adapts the popular technique of storytelling by assuming different roles and enacting them. In Janata Raja, the shahir uses these techniques to narrate and also critique a given situation throughout the play. He, along with the chorus, functions as the narrator of the play.

The play employs tamasha (a performance art form of Maharashtra) where the soldiers of Bijapur king Ali Adilshah II are busy in enjoying the lavani (a popular Marathi song and dance performance), and Shivaji’s army under the leadership of Kondhaji Farzand attacks them and conquers the fort.[4] (Fig. 3)

Along with performance traditions, the play also uses elements from philosophical traditions such as the Bhakti. Abhanga, a devotional poetic composition, is borrowed from the Bhakti poets and is sung by the character of Saint Janabai. Similary, gondhal, a dramatic narration of mythological stories, usually performed to invoke and seek blessings from gods and goddesses, is also imported from Bhakti. In Janata Raja, after the killing of her family, an enraged Jijabai, who is pregnant with Shivaji, calls upon Goddess Bhavani as gondhal is performed in the background.

The mahanatya borrows heavily from folk traditions to narrate particular events from Shivaji’s life. For instance, the waghya-murali (waghya means lion which represents the male dancer in this context and murali, which means flute, is the female devdasi dancer) devdasi dance is performed in the scene where Shivaji imprisons his uncle Sambhaji Raje Mohite because he loots from the poor of his own estate. There is a performance by the Kolis (a fishing tribe from the Konkan region of Maharashtra), who were enslaved by the Portuguese before being freed by Shivaji. In Janata Raja, the Kolis are shown as invitees at Shivaji’s coronation ceremony, where they perform their folk dance. Similarly, there is also the use of ghazal (a form of love song) that helps create the atmosphere at Mughal general Shaista Khan’s camp, which is attacked by Shivaji’s troop as it captures the Red Fort in Pune.

The play is laced with several such folk art forms. The play includes characters belonging to different religions, caste and race. It depicts the Mughals, Christians, Hindus, Dutch, British, Koli, Brahmins, Kshatriyas, etc. The text is multicultural, multi-religious, and even multilingual; Henry Oxinden from the East India Company, for example, speaks in English at the coronation ceremony.

Main characters in Janata Raja

Throughout the play, just three characters hold the spectator’s attention—Shivaji, his mother Jijabai and the shahir. The other characters are like montages. They have specific scenes, but they only come alive through the three characters. The shahir is the character who narrates the story to the audience through powada. Jijabai is Shahaji’s wife and is responsible for urging her son for an uprising; her character ages through the play and she puts up a spectacular performance at the coronation ceremony.

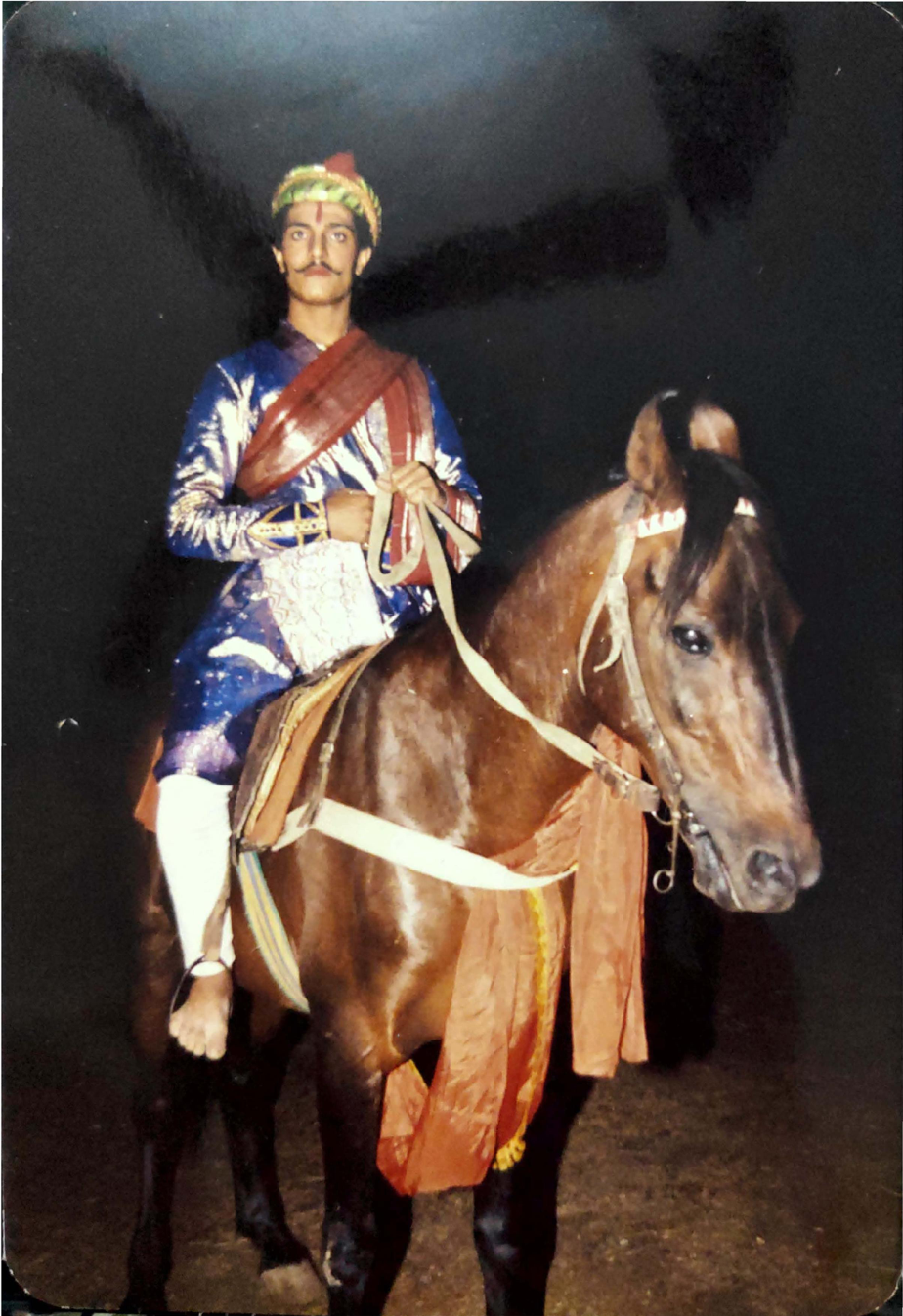

The character of Shivaji is played by three different actors—the child Shivaji, young Shivaji and adult Shivaji. Initially, the actors were trained by Babasaheb Purandare himself. The acting style of the Shivajis specifically as well as that of Aurangzeb and a few others, is classical, in the sense that it incorporates grand gestures and stance which is not necessarily in accordance to modern-day realistic acting. (Fig. 4)

Actors, director, sound and light technicians and audience influence the production of a play. Their actions have consequences that can change the overall play. However, Janata Raja is different among the genre of historical plays. The dialogues of the characters are recorded in quadraphonic sound, or what we today call the 4.0 surround sound system. There is no natural and direct dialogue delivery by the actors, who are restricted to lip-syncing to the recorded version. There is a very little scope for improvisation; the actors cannot change any lines. Their actions and steps on stage are set to the rhythms and timings of the recording. The sound and lights of the play are also bound with the narrative.

The play, which has successfully been performed over a thousand times, with spectators pouring in, has had few modifications. One needs, therefore, to examine why this version of history disseminated through the play is so rigid and leaves no scope for improvisation on stage, especially by actors.

The explanation offered by the current director, Yogesh Shirole, is that recorded dialogues are used to maintain the grandeur and dramatic effect of the play. ‘The sound and light, along with the text and the elaborate costumes are the soul of the play,’ he says.[5]

The stage for Janata Raja, however, has evolved over the years. The play employs the proscenium as well as the foreground for the actors to take their entries on animals such as horses, elephants and camels. (Fig. 5) This spectacular nature of the play and the contexts in which it is performed gives it performative value and popularity. The context enhances the potential of the play’s performativity and each time uses the mimetic figure of Shivaji to proliferate a certain worldview.

In an interview with Pradeep Bhide, which can be found on YouTube, Purandare talks about using the form of drama to propagate the life and work of Shivaji. He says: 'At the end, the play is not the history. It is the reflection of history that the play shows. Then why should one write a play? One should read a thesis! But people do not come to listen to a thesis. People come to see the reflection and hear the echo.'[6]

Justifying his use of the medium of drama, Purandare pushes the ball in the audience’s court and hints towards the popular culture that engages more in entertainment rather than reading a thesis or attending a lecture. A play filled with spectacular props, sets, animals and fireworks creates a thrill as well as pride interlaced with a specific worldview and politics of representation of the icon due to its selective portraiture of events from Shivaji’s life in the Ramrajya (reign of Lord Rama) narrative—fights with Mughal kings are part of the play but no battles with Hindu rulers are shown.

The play depicts several smaller incidents from Shivaji’s life to present a just and noble image of him towards his ryot (workers, usually farmers). Although, as a performer in the play for the last 18 years I get carried away by its overpowering sound and the overall spectacle, I cannot resist asking questions about the contexts, dramaturgy, use of certain symbols, and its selective narrative.

The play fails to provide an unbiased portrait of Shivaji and instead reinstates his hagiographic image. While Purandare has done an excellent job in studying through available sources the minute peculiarities of the seventeenth century, his selective approach paints the portrait of Shivaji only through one perspective. The 90-foot stage; use of animals like elephants, camels and horses; display of martial arts; and narration through the instigating and provoking powada style awes the audience; but a close observation unveils the problematic history that it presents, with Shivaji shown in the light of bakhar (hagiographic) literature. The rhetoric used in the play, interspersed with poetry, creates a make-believe image of Shivaji, thus moving far from historical facts.

Notes

[1] Maharaja Shivchhatrapati Pratishthan, ‘Shivasrushti 1974.’

[2] Shaikh, ‘Worker Politics, Trade Unions and the Shiv Sena’s Rise in Central Bombay.’

[3] Guardian Media & Entertainment, ‘Janata Raja Part 1 of 2.’

[4] Tamasha is a form of storytelling that evolved from earlier folk forms of Maharashtra and became distinct only in the later Peshwa period. Lavani, a song sung along with dancing, is an essential part of Tamasha and is usually erotic and suggestive.

[5] Shirole, in conversation with the author.

[6] Guardian Media & Entertainment, ‘Janata Raja Part 1 of 2.’

Bibliography

Guardian Media & Entertainment. 'Janata Raja Part 1 of 2.' YouTube Video Channel: Mahesh Phundkar, 48:26. April 20, 2017. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nvYfQXNvus.

Maharaja Shivchhatrapati Pratishthan. 'Shivasrushti 1974.' Maharaja Shivchhatrapati Pratishthan. Accessed October 15, 2019. http://www.msptrust.org/shivsrushti.html.

Shaikh, Junaid. 'Worker Politics, Trade Unions and the Shiv Sena’s Rise in Central Bombay.'