Eighty odd years after the institutionalization of Mohiniyattam at the Kerala Kalamandalam, it is safe to say that four distinct traditions have come to be established in it. Bani, derived from Sanskrit, literally means 'voice'. Loosely translated as 'tradition' or 'school' in most dance and music related writing, a bani is the result of a process of creative evolution, organic as well as deliberate. Repetition of a particular form of stylization by successive performers establishes a bani. However, it remains rather fluid in its structure as continued evolution and redefinition keeps the form itself alive. The evolution of Mohiniyattam has led to the establishment of four major traditions—the traditions of Kalamandalam, Kalyanikutty Amma, Bharati Shivaji, and Kanak Rele.

Kalamandalam and Kalyanikutty Amma

The early twentieth century saw a revival or reconstruction of dance in South India, spurred on by the developing Indian nationalist movement. The ban on temple dancing and the reconstruction of Bharatanatyam from Sadir in Tamilnadu is a relatively well-studied consequence of this movement. Reverberations were felt in Kerala as well, where the poet Vallathol Narayana Menon spearheaded the movement to establish Kerala Kalamandalam. Kalamandalam was inaugurated in 1930. Kathakali was the only form taught initially at the Kalamandalam. Vallathol’s attempt to establish Mohiniyattam at the Kalamandalam was met with certain challenges. The popular sentiment, influenced by the anti–nautch movement (which resulted in the ban on temple dancing), and social upheavals in Kerala, was strongly against this female dance form. Hence it was difficult to find teachers as well as students for Mohiniyattam which had fallen into disrepute.

After an extensive search by the poet, Orikkaledath Kalyani Amma, a retired Mohiniyattam dancer from Peringottukurissi, was brought to Kalamandalam in 1933. Thankamani was the only student for Mohiniyattam and joined after much persuasion from the poet. So strong was the sentiment running in the society against this from of dance in those times! Thankamani left after getting married to Guru Gopinath. In 1936, Kalyani Amma also left for Shanti Niketan at Tagore's request. Thus Mohiniyattam training ceased at the Kalamandalam.

In 1938, Madhavi Amma and Appuredath Krishna Panicker, a well-known Nattuvan from Korattikkara, joined Kalamandalam. It was during this time, Kalyanikutty Amma (not to be confused with O. Kalyani Amma) was persuaded by Vallathol to learn Mohiniyattam. That Kalyanikutty Amma, a girl from a well-known family, marked her entry into Mohiniyattam, persuaded four more girls to join. It was exactly what Vallathol had hoped for. That when girls from good families took up Mohiniyattam it would re-establish its social acceptance. Kalyanikutty Amma had her arangettam or debut in 1939. She left Kalamandalam in 1940 after getting married to Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair, a renowned Kathakali actor. She later established her own school. Krishna Panicker and Madhavi Amma also left in 1941 due to age related ailments. In 1946, Thottasseri Chinnamu Amma joined Kalamandalam. Even though she had briefly trained under Krishna Panicker, her guru was Kalamozhi Krishna Menon. Chinnammu Amma retired in 1964. Her students including Kalamandalam Sathyabhama formed the faculty following her retirement.

Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, in her book, Mohiniyattam Charitravum Attaprakaravum, mentions that when Orikkaledath Kalyani Amma was brought to Kalamandalam, her dance had some 'indecent' aspects to it. She goes on to mention some of the changes made by Vallathol at Kerala Kalamandalam.

- He stopped the practice of the nattuvan following the dancer on the stage playing cymbals and reciting vaytharis. The nattuvan and accompanying artists were given a place to sit at the right hand side of the stage as opposed to standing close to the dancer.

- It was decided to continue the Carnatic music system which was in place since the time of Swati Tirunal. Toppimaddalam, titti (a kind of bagpipe), and mukhavina were removed and mridangam, violin, edakka, and flute were included in the pakkavadyam.

- Some controversial pieces in the repertoire like mukkuthi, and chandanam were removed.

- Hastalakshana Deepika was introduced as the basis for mudras in addition to the gramya (realistic/rustic) mudras and tantrik (ritualistic) mudras used in it.

- A classical framework based on chaturvidha abhinaya was insisted on while retaining the gramya and lokadharmi aspects of the dance.

We get a brief idea of the repertoire taught by Krishna Panicker from Kalyanikutty Amma’s book. This included a cholkettu, jatiswaram in Bhairavi, varnam in Yadukula Kamboji, padam in Punnagavarali, and tillana in Arabhi. He also taught the two items of slokam and saptam which were no longer performed. Kalyanikutty Amma went on to choreograph new pieces in these two categories as well as ashtapadis after she left Kalamandalam. Saptam remains specific to the repertoire of Kalyanikutty Amma tradition. The format of a typical Mohiniyattam performance is in the following order—cholkettu, jatiswaram, varnam, padam, tillana, slokam, and saptam.

Dr Neena Prasad in her article, Traditions in Mohiniyattam: A closer look, mentions the remarkable differences between the Kalayanikutty Amma tradition and the Kalamandalam tradition of Mohiniyattam. These include the basic stances, the construction of adavus, and the mode of swinging the upper torso, the aharya, and the repertoire. While Kalamandalam bani developed from Chinnammu Amma, who was primarily a student of Kalamozhi Krishna Menon, Kalyanikutty Amma’s tradition springs from the teachings of Krishna Panicker. Kalyanikutty Amma developed a syllabus for teaching Mohiniyattam by codifying and creating adavus, karanas, padas, and charis in order to provide a strong foundation for teaching. She also composed many pieces to expand the repertoire of Mohiniyattam. She travelled across the state on a research fellowship trying to glean information on the history of this dance form. Amma, in her book, lists certain criteria to be adhered to in Mohiniyattam. The basic stance employs only two inches of distance between the feet. The footwork should be soft and the arms move within a certain circumference close to the body. The movements should be soft like 'tender paddy leaves swaying in a gentle breeze'. Adavus showcase a characteristic bobbing movement with the dancer alternating between aramandalam and kalmandalam positions. The dancer does not rise higher than kalmandalam position while doing adavus. The knee is not straightened completely during teerumana adavus. The mudras are based on Hastalakshana Deepika in addition to the gramya and tantric mudras which existed in Mohiniyattam beforehand. Abhinaya darpanam is the text on which interpretive dance is based. While navarasas are depicted in Mohiniyattam, the dancer stays within the limits of the lasya. Hip movements, lifting legs above the knee level, as well as leaps and jumps are avoided.

Aharya or costuming finds specific mention. A 'cela' or sari, eight yards long, white in color with golden border was worn in the past. A stitched costume is worn these days. However, Kalyanikutty Amma’s school follows this color combination strictly. The hairdo was either in 'Kakapaksham' or 'Nagalambam' styles. Nagalambam was more commonly used and followed by Kalyanikutty Amma. The hair is plaited down the back and adorned with jasmine flowers at the nape of neck, and etaminni or small gold plated discs in graduating sizes is attached to a thread and tied into the braid. Netti chutti adorns the forehead and suryachandranmar (sun and mon) are also worn on either side of the head.

In 1942, Thottasseri Chinnammu Amma, disciple of Kalamozhi Krishna Menon and Krishna Panicker, joined Kalamandalam as faculty and stayed on for the next fifteen years. Her students formed the faculty upon her retirement in 1964. Chinnammu Amma had learned Mohiniyattam in her youth, and had stopped dancing after she got married. She was approximately fifty years old when she joined Kalamandalam. She had forgotten much of what she had learned. Her repertoire included a cholkettu in Chakravakam, a padam (Enthaho Vallabha), two jatiswarams in Chenchurutti and Todi ragams, and a telugu varnam in Yadukulakamboji. (This detail has been refuted by Kanur Krishnan Nambudiripad, researcher and scholar, who states in an interview that Chinnammu Amma’s repertoire included only a cholkettu and a varnam). Training at the Kalamandalam consisted of these pieces and also of the female roles in Kathakali. Sathyabhama, one of Chinnammu Amma’s early students, went on to contribute immensely to the reconstruction of Mohiniyattam in Kalamandalam. She reminisces how the students were also sent to another old Mohiniyattam dancer, Kapuratte Kunjukutty Amma, in an effort to learn more. However, Kunjukutty Amma was quite old and there was no cohesion in her day to day teaching. Sathyabhama was also sent to Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma from whom she learned a few pieces. This was an effort to find a common ground between the two traditions. However, Sathyabhama explained in an interview that the two styles were different enough for her to decide to build further on Chinnammu Amma’s tradition. Kanak Rele, dancer and researcher, filmed the repertoire of Kunjukutty Amma, Chinnammu Amma, and Kalyanikutty Amma during 1970-71. In her book, Mohini Attam, the Lyrical Dance, we find evidence of the considerable differences between the styles of these women. While Kunjukutty Amma’s style was forceful and vigorous, Chinnammu Amma’s style was soft, and lyrical, with rounded movements but firm footwork. Sringara abhinaya predominated in her style. Kalyanikutty Amma’s style was vigorous, with firm footwork, and marked by sharp execution and powerful abhinaya.

After training for six years in Kalamandalam, Sathyabhama joined as junior faculty in 1956. It was during her time in the institution that much of the basics and the repertoire of Kalamandalam tradition were developed. She was guided and helped by the poet Vallathol, scholars such as Killimangalam Vasudevan Namboothirippad, and artistes such as N.K. Vasudeva Panicker (vocalist and violinist), Ramakrishna Iyer (mridangam artiste), and her husband Kalamandalam Padmanabhan Nair, the eminent Kathakali artiste. She went on to codify about sixty-five adavus, some of which were borrowed from Kathakali and modified to fit the form of Mohiniyattam. A full repertoire was worked on, which began with cholkettu and progressed through jatiswaram, varnam, padams, and finally tillana. Kalamandalam Sathyabhama choreographed several major compositions that forms the traditional repertoire of Mohiniyattam. The four major varnams of the Kalamandalam tradition—Danisamajendra gamini in Todi, Sumasayaka in Kapi, Manasime Paritapam in Sankarabharanam, and Ha Hanta Vanchitaham in Dhanyasi—are her contributions. She also choreographed eleven padams and a tillana. Group choreographies and dance dramas in Mohiniyattam were also created by her during the 1960s.

The Kalamandalam tradition maintains a wider gap between the feet in the aramandalam position, and presents less transition between kalmandalam and aramandalam positions while doing adavus thus maintaining a more stable aramandalam. The head moves in line with the body and is stable with eyes glancing sideways with movement. A notable contribution was in the aharya, specifically the hairdo. Kalmandalam Sathyabhama introduced the side bun with the hair bunched up on the left side and adorned with jasmine flowers. This was inspired by Raja Ravi Varma’s paintings of the women of Travancore royal family. This style was tried on Kalamandalam Sugandhi in 1965 at a function to celebrate Mahakavi Vallathol’s birthday. The side bun soon became widely accepted but was criticized by Kalyanikutty Amma as a departure from the dasiattam tradition.

Justine Lemos in her paper, Radical Recreation: Non-Iconic Movements of Tradition in Keralite Classical Dance approaches the process of reconstruction of Mohiniyattam from a limited repertoire. She argues that in addition to the iconic replication (mimicking of gestures and movement by students), 'co-presence' of elderly Mohiniyattam dancers contributed to the establishment of the tradition. While Mohiniyattam underwent radical reinvention at the Kalamandalam, the process remained within the organic framework provided by teachers such as Krishna Panicker and Chinnammu Amma.

Bharati Shivaji

By the 1950s Mohiniyattam had ventured gradually out of the boundaries of Kerala. In 1958, Kerala Kalamandalam presented Mohiniyattam at the All India Dance Seminar in Delhi. Dancers from out of Kerala such as Indrani Rehman, Tara Chaudhary, and Shanta Rao who studied at the Kalamandalam started presenting Mohiniyattam as part of their dance recitals. This is how Bharati Shivaji, already trained in Bharatanatyam and Odissi, came to watch a Mohiniyattam recital presented by Indrani Rehman in Delhi. She was mesmerized by the graceful aspect of this dance form. Bharati found a teacher in Delhi–Radha Marar who had trained at Kalamandalam. She learned the basic adavus and the few pieces of the Kalamandalam repertoire, and also started performing in Delhi.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, the former chairperson of Sangeet Natak Akademi, offered Bharati a scholarship to go to Kerala and research in Mohiniyattam. She travelled to Kerala in the 1970s to work with Kavalam Narayana Panicker, who was a scholar, poet, and dramatist. Kavalam’s vision was to integrate the regional music of Kerala (Sopana Sangeetam) into Mohiniyattam in order to give the dance form a wholesome regional flavor. Under his guidance, Bharati delved into the immensely rich performing arts traditions of Kerala, both folk and classical, including Krishnanattam, Kutiyattam, theyyam, patayani, Arjuna nritham, ottam thullal, and kaikottikali. She travelled all over Kerala meeting old dancers and surveying the various aspects of Kerala’s culture such as temple architecture, sculptures, paintings, music traditions, theater traditions, rhythm patterns tc. During this time, she also trained with Kalamandalam Kalyanikuttyamma.

Bharati started working on codifying the basic dance movements and reconstructing the repertoire by judiciously incorporating elements from the other performing art forms of Kerala. She also looked beyond the existing literature for her choreographies thus adapting manipravalam literature of Kerala (Chandrotsavam), Gita Govindam, and Bhanushinger Padabali of Tagore among others. Majority of adavus are from Kalyanikutty Amma’s tradition. However their treatment is quite lyrical with more looseness in the upper torso and neck movements.

Vinaya Narayanan, Bharati Shivaji’s senior disciple, had this to say about the embodied experience of dancing this particular style during a personal communication. 'There is freedom of movement given to the upper body. There are no hard rules as to how far you can bend and twist. It differs from person to person as the body proportions vary. The limits are set by the dancer herself based on a thorough understanding of the aesthetics. Neck is kept relatively loose and follows the pattern of body movement. Another thing that I have felt is, we engage the core muscles, probably the solar plexus area, more for our chuzhippus. So, there is always an internalizing of the movement, which is more felt by the dancer than seen by the onlooker. This is not consciously taught to us. But over time we come to realize the importance of internalizing a movement.'

Bharati Shivaji founded the Center for Mohiniyattam in New Delhi for training, research, and promotion of Mohiniyattam. She and her daughter Vijayalakshmi, along with their students have taken Mohiniyattam to a multitude of venues, both national and international. Vijayalakshmi has been taking her mother’s work forward by exploring new ideas to be incorporated into Mohiniyattam. The use of a completely different genre of music by adopting the Russian composer Tchaikovsky’s score for her production Swan Lake merits special mention.

Kanak Rele

Dr Kanak Rele is yet another renowned artiste from outside Kerala who made significant contributions to the growth of Mohiniyattam. Trained from a young age in Kerala’s theater form Kathakali, it was perhaps natural for her to develop an interest in the lasya dominant dance from the same region. Her training in Kathakali was under Guru Panchali Karunakara Panicker. She was already an established Kathakali performer when she started training in Mohiniyattam under Kalamandalam Rajalakshmi. Despite the immense appeal of the highly lyrical form, she was frustrated by the limited repertoire. She travelled to Kerala on a grant from the Sangeet Natak Akademi and later with a Ford Foundation grant. In 1970-’71, she was able to film Kunjukutty Amma, Chinnammu Amma, and Kalyanikutty Amma—oldest surviving dancers of the form. She developed her own style based on this material and texts such as Natyasastra, Hastalakshana Deepika, and Balaramabharatam. In 1977, she was awarded Ph.D for her doctoral thesis on Mohiniyattam. She met Kavalam Narayana Panicker in 1983, who introduced her to his concept of incorporating Sopana Sangeetam into Mohiniyattam. The collaboration with Kavalam who was a scholar with in- depth knowledge in Kerala’s indigenous music system resulted in more than fifty choreographies.

In her work, Mohiniyattam, the Lyrical Dance, she theorizes a strong foundation for Mohiniyattam based on Natyasastra with particular reference to Balaramabharatam. The detailed angika abhinaya finds basis in these classical texts and shares the interpretive nature of Kerala’s theatrical forms. Kanak Rele put forward a 'Theory of Body Kinetics' based on her research in movement studies. She introduced a classification of the geometrical patterns found in the Indian classical dance based on the theories of 'volution' and 'revolution (spiral)'. Volution creates precise geometrical patterns with the lower half of the body following rhythmic patterns (footwork) and the upper half moving in semicircles while connected at the waist as the center. Revolution creates a lyrical atmosphere, with well-rounded movements of the upper half which is made independent of the lower half with the center back part of the waist acting as a pivot. Mohiniyattam of course belongs to the second group. She also came up with sketches to explain these movements and the karanas adapted as adavus in Mohiniyattam from Natyasastra. She developed a set of basic dance movements (adavus) based on her theory of body kinetics. These movements are classified based on the part of the body that has a predominant role in a set of movements. Rele’s style employs a wider gap between the feet in the basic stance as well as wider swings and circularity in the chuzhippu movements. She established the Nalanda Dance Research Centre and the Nalanda Nritya Kala Mahavidyalaya.

Sopanam in Mohiniyattam

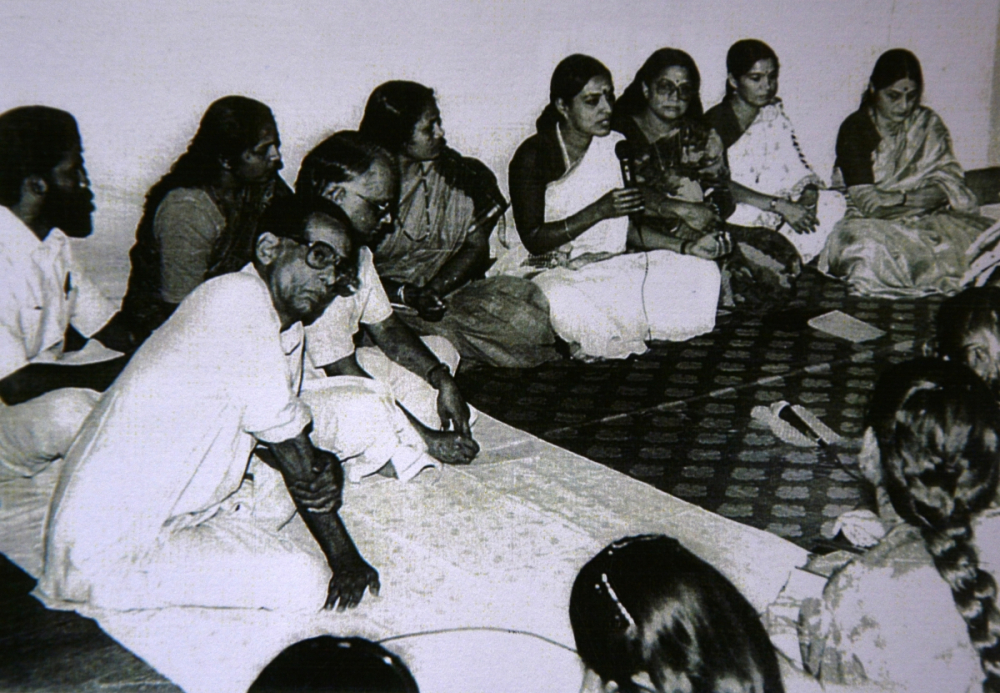

Kavalam Narayana Panikker with Bharati Shivaji and Kanak Rele

By 1970s Mohiniyattam had become established at the Kalamandalam and also had started making its presence felt outside Kerala. The repertoire and music tradition were derived from the Swati Tirunal period which had the unmistakable influence of Karnatik and Bharatanatyam traditions. It was during this time Kavalam Narayana Panicker proposed the introduction of Kerala’s traditional music and rhythmic patterns into Mohiniyattam. The purpose was to give Mohiniyattam a distinct regional flavor rooted to Kerala’s soil. Interestingly, the initial takers for this movement were from outside Kerala—Bharati Shivaji and Kanak Rele. They developed movement patterns fitting the Sopanam mode of singing. This movement resulted in an alternative repertoire format for Mohiniyattam—Ganapathy, mukhachalam, niram, padam, tatvam, and jeeva. More recently, the dancers belonging to other schools such as Vinitha Nedungadi, Methil Devika, Pallavi Krishnan, Kalamandalam Sugandhi, and Nanditha Prabhu have adopted this school of music. The development of Sopanam tradition in Mohiniyattam thus transcends disparate schools and merits a study of its own.

In conclusion, since its reconstruction at the Kerala Kalamandalam, Mohiniyattam has evolved into four distinct traditions based on its movement vocabulary. However, traditions in art remain flexible and these forms undergo constant reinvention as individual styles diverge over time. It is this dynamic process that keeps the art forms alive and prevents their fossilization.