Traditional Tribal Textiles of Bastar

Textiles of a region provide a medium to showcase man’s journey in life, events and occasions. Many of the material, techniques and forms used from ancient times remain in use even today, both as an essential aspect of production in many regions of the world and as ingredients in textile arts (Schoeser, 2003). Tribals are a part of the mainstream in but a few regions; they mostly remain secluded, and maintain distinct identities reflected in their attire and ornamentation.The word ‘tribal’ denotes a social group, comprising a series of families, clans or generation (Bhavnani, 1969). Within India, their concentration lies in a belt starting from Madhya Pradesh to Bihar, Odisha, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and all North Eastern states of India.

Textile historians have noted some features seen across tribal art forms and crafts (Bhavnani, 1969). Firstly, each tribal region has unique designs and forms that reflect their lifestyles, religious beliefs and observances. Secondly, each tribal group emphasizes some form of creative expression, which gives it a distinctive identity

Elwin (1992) has noted that the artistic and creative expressions of adivasis or tribals are part of their mythology and draw from the vitality of their world view. Inspired by legends and folklore, and rooted in their everyday life, motifs and patterns found in their crafts carry deep significance. Each community expresses its identity through a sense of aesthetics that evolved from a specific aspect of their history including migration patterns.

In case of weaving, the patterns woven by the tribals are abstract in form, with an acute sensitivity to colour and texture. This is expressed in the variations of stripes and geometric shapes, which create interesting and harmonious patterns (Dhamija, 1997).

Inhabitants of Bastar

In 2000, Madhya Pradesh was split into Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. The Bastar district in Chhattisgarh is the melting pot of art and craft, which is evident in the textiles, bell metal and terracotta. This region was divided into Kanker, Bastar and Dantewada. Bastar and the neighbouring Koraput in Odisha are home to tribal culture and traditions, nurtured by the land’s endowed with natural resources.. The natives of these regions are skilled craftsmen. They are simple, hardworking and work with varied medium such as clay, terracotta, metal and textiles. Their designs and crafts are inspired from the forms found in nature and their observations and interpretation of objects and hence have a naïve appeal.

According to a survey done by the Government of Madhya Pradesh in 1997, there were more than 3,000 artisans in Bastar alone, who were earning their livelihood by working with bamboo, metal, wood, textiles and clay. Bastar is the hub of tribes, who have been isolated from the mainstream Indian society and culture because of the physical barrier of the dense Dandakaranya forest.

Natural Dyeing and Handloom Weaving in the Tribal Regions of Chhattisgarh

One of the lesser-known textile crafts from this region are the aal (Morinda citrifolia) dyed handloom fabrics used mainly as a sari by the tribal women and as a turban or a shoulder cloth by men.

Weaving of aal-dyed textiles is known to the Bastar region since the 16th century, which was most probably brought from the village Kotpad in the district Koraput of the neighbouring state of Odisha. However, there are no records or reference of it in the form of a sample or text.

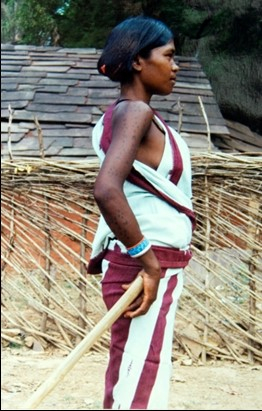

Villages such as Tokapal, Nagarnar and Kondagaon in Bastar had weavers who were experts at dyeing and weaving of aal-dyed fabrics (Singh, Chishti and Sanyal, 1989). Earlier, each village used to grow their cotton crop for weaving. The natural base or unbleached cotton yarns are used for the body of the pata, a sari-like drape worn by the women of Muria and Maria (Plate 1). The woven cloth known as phatai is made manually on pit looms. The process of weaving traditional pata is known locally as phatai bunana.

Plate 1- A Tribal Woman Wearing Pata

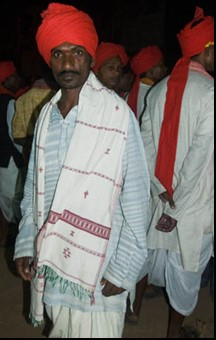

Men wear angoccha, a shoulder cloth also used to cover the head in the sun. Men from the Dhurva tribe wear a turban known as pheta which is six feet long and twelve to fourteen inches wide (Lynton, 1995) (Plate 2).

Plate 2- A Tribal Man Wearing a Pheta and Picchori

There are mainly three weaver’s communities---the Pankas, the Chandhars and the Mahars, who still maintain a social and religious distinction. Though they cater to the needs of their residing region, they weave different types of fabric based on their specific levels of skills (Singh, Chishti and Sanyal, 1989). The Pankas consider weaving a lowly occupation. The principal occupation of the Mahars was weaving of coarse cloth. The Chandhars used to weave coarse, low-count textiles, which were usually made into heavy floor coverings, and covering for cots and cart linings (Balaram, 1999). The Pankas were skilled weavers and produced the heavily ornamented textiles, patas and phetas (Singh, Chishti and Sanyal, 1989).

The region remains the only area in Central India where tribal textiles are woven using natural aal dyed cotton yarn. The aal dyed textiles were not only popular with the tribals of Bastar and nearby areas, but also with people belonging to higher class such as Brahmins. The use of aal dyed fabrics by the local population of tribal women has diminished, as only old tribals wear it, that too, occasionally.

The Pankas, belong to the Dravidian caste of weavers. They are the followers of the founder of the sect, the Indian mystic poet Kabir (ad 1440endash1518). Since Kabir was a weaver, they also practice weaving and are known as ‘Manik Puri Pankas’ or ‘Kabir Panthis’. The Pankas are also called panika, which means ‘from water.’ Kabir was brought up and raised by a Julaha or Muslim weaver who found him lying on the lotus leaves in a pond. This has given rise to the following rhyme about the panikas:

Pani se panika bhae, bundan rache shareer

aage aage Panka bhae, pachhe das Kabir

Which may be rendered, ‘The Panka indeed is born of water, and his body is made of drops of water, but there were Pankas before Kabir’. Another rendering of the second line is, ‘First he was a Panka, and afterwards he became a disciple of Kabir’ (Russell and Hira Lal, 1969).

The Pankas are skilled weavers and produce heavily ornamented textiles commonly known as Patas and phetas. These are straight lengths of fabrics which are draped as saris and turbans.

Mahars are of Rajput decent while some say they are non-Aryans. The principal occupation of Mahars is weaving of coarse cloth (Balaram, 1999). The Chandhar is a small community of weavers, probably an occupational group formed from members of the Dravidian tribes. They weave coarse low count textiles, which are usually made into heavy floor coverings, covering for cots and cart linings (Singh, Chishti and Sanyal, 1989). Tribals consider weaving as a lowly occupation; hence all weaving related work is done by non-tribal weaver castes.

Textiles of Bastar

As per the beliefs of the weaving communities in Chhattisgarh, Devangans were blessed with the knowledge of weaving by the goddess Mother Durga. She taught them to produce fibre from a lotus stem and directed Lord Vishwakarma to make the shuttle out of the bones of Maikasur Danav. The hair of the asura was made into a brush for sizing a yarn. His ribs were used as base to hold the warp apart and so on, till every bone was put to good use.

According to Nandram Devangan, weaving was first learnt by the Devangans who then taught the craft to the weavers of Kosa silk. These weaves are now known as the Koshtas. Later, it was taught to the elected spokesmen known as the Mehers. The Pankas, the Julahas and other castes learnt weaving by watching the Devangan Koshta and Meher weavers (Singh, Chishti and Sanyal, 1989).

Till a few years ago, weavers were requested by the tribals to weave lugda or pata for special occasions. The weavers were paid in cash, grains and other produces from the field. The tribals traditionally value the sari’s worth by weight and workmanship and looked at a fabric’s density and strength. However, the women from urban as well as non-urban regions show a preference for the sari’s aesthetic appeal and how light the fabric is in weight.

Since the 70s, traders from across India made inroads into the secluded tribal belt to sell everything from cheap mill prints to power loom imitation of handloom and more recently synthetic fabrics. Bastar and the southern region of Chhattisgarh have seen tremendous growth in sari weaving and fabric production, while the northern tribal districts and the central region have seen a gradual decline.

Some of the commonly woven aal dyed handloom products are:

Pata: A pata is a draped textile like a sari. The background is off-white with aal-dyed red borders and extra weft ornamentation (Plate 3). Some patas are for routine wear whereas certain designs, placement of motifs and methods of draping differ for ceremonial or special occasions. Usually a pata is around–fourr meters long and one meter wide and is made of low count coarse cotton yarn of 10s, 14s or 20s.

Plate 3- A Woman Wearing a Pata

Tuvaal: It is a piece of fabric used as a shoulder cloth by men in Bastar. It is three feet wide and six feet long. It is generally folded and draped on the shoulder but is wrapped like a shawl in cold evenings. For festivals and ceremonies, tuvaals with ornamentation are preferred. Most often the base is off white, ornamented with aal-dyed red yarn in extra weft to create motifs inspired from nature.

Picchori: It is the lower garment for men, draped like a wrap-around dhoti (Plate 4). The dulha picchori is a special ornamented shaal -like fabric which is worn by a bridegroom.

Plate 4- A Man Wearing a Picchori

Shaal: The length and width of shaal varies but most often it is one meter wide and around two meters long. Shaals meant for ceremonies or festivals are woven with aal-dyed red yarn as the base colour and extra weft ornamentation in off-white.

Chaddar: Like tuvaal and shaal, it is 45 inches wide and 90 inches long. Men also wear it around the neck or like a sheet to protect themselves from heat or cold (Plate 5).

Plate 5- Man Wearing a Chaddar During Dussehra Mela

Chaptati: It is a running fabric woven using alternate red and white yarn in warp as well as weft to create checks. The width of the fabric is either 36 inches or 42 inches. It looks like a fine woven mat (chatai) and is used for making kurta, baniyan (undershirt), bandi (sleeveless short jacket), etc.

Angoccha/Angocchi: It is a short length of narrow width fabric which is generally placed on the shoulder. These are used to cover the head in the sun. Angoccha is also sometimes known as angocchi. It has fine red line borders running weftwise and one inch-wide red bands on the two ends, pallu (Plate 6).

Plate 6- Man Wearing a Simple Angoccha (A- Front and B- Back)

Dhoti: It is a plain length of white fabric with a fine red edge, worn or draped as a lower garment in varied styles by men all over India,. A kurta is worn with the dhoti and the angoccha for special occasions. Otherwise readymade cotton or cotton- and- synthetic-blended shirts are worn with the dhoti and angoccha, while going out.

Kansbandhi: It is an ornamental dhoti length of textile woven with wide aal-dyed ends or pallu and off-white central field. It has many motifs woven on the body as well as on the borders and pallu. In Bastar, men wrap the kansbandhi around the waist while dancing.

Phenta: It is around three and a half meters long and approximately 15–18 inches wide fabric which is tied around the head by men like a turban. It is generally ornamented and is worn on special occasions.

Consumers/Users of Traditional Pata

The sari is known by different names such as dhoti, pata, lugda, kapda, sadlo and many other names in various parts of the country. In Bastar, however, the local names for sari-like drape was pata, luga and dhoti. The width and the length might also vary and the way it is worn can also be different. It is predominantly used by the women belonging to the Murias and Marias for regular wear. These tribes are of higher status in the hierarchy of tribal society.

Shrimati Premvati Panka, the wife of a weaver from Nagarnar says that tribal and non-tribal women draped the pata differently. There patas were draped in two different styles—‘chendra and ganthi marna—and was worn without an underskirt or a blouse. Ganthi marna means to make a knot, a style of draping preferred by the Marias, Murias and Pankas (Plate 7). In this style, the pata is wrapped around the body, leaving one end loose at the back which is tied with the end of the front flap on the right shoulder. This covers the shoulders and is hence worn when going out.

Plate 7- A and B Pata Draped in the Ganthi Marna Style (A- Front and B- Back)

Other Styles: Chendra is a daily wear style where the ends are tucked in the waist band formed by wrapping the Pata around the waist (Plate 8). The right shoulder remains bare. However, the front flap can be easily opened like a pouch to carry grains, fruits, etc.. In both the styles, patas are worn in an adjustable wrap over style, till mid-calf length.

Plate 8- A Pata Draped in the Chendra Style (A-Front and B- Side View)

According to Shri Sadan Das Panka, a National Award-winning weaver from Tokapal, The Panka women also started wearing simple patas for weddings and special occasions since the 1980s. Ornamented patas were woven on order for the tribalsduring the wedding season.

Presently, tribal women have also stopped wearing patas. A few old tribal women were seen at the local weekly haat known as Madai, wearing pata. One of them, a Dhurva woman was wearing the aal-bordered simple pata which was draped quite raised till the knee-level (Plate 9). Some Dhurva men were also seen wearing the aal striped angocchi and tuvaal (Plate 10).

Plate 9- Dhurva Woman in Knee-length Pata in Chendra Styles

- Front View and B- Back View)

Plate10- Dhurva Man Wearing a Traditional Angoccha and Tuvaal

It was significant to note that the aal-dyed traditional textiles were now worn only on special occasions by the localsowing to their high cost. Although it was reported that aal dyed patas were specially woven on order during the wedding season, investigations revealed that ritualistic or social significance for the fabric is there but none to the motif.

The motifs, even though appear geometric, are inspired from the easily recognizable flora, fauna and objects in their houses. The designs woven on the pata and other aal dyed textiles were varied and striking due it its contrasting colours and simple forms.

At present, the local demand of traditional pata, angocchi and picchori is very low. The reasons are the availability of other cheaper and maintenance-free options, such as brightly-coloured printed synthetic saris, chequered shirts and matching synthetic angocchas(Plate11 and12).

Plate 11- Women Wearing Synthetic Saris as Patas

A traditional craftsman is a storehouse of indigenous knowledge, which is not always documented. Some of these oral traditions are lost forever, especially at this juncture, when the artisans are searching for avenues for livelihoods. Hence the knowledge of some of the traditional textile techniques such as dyeing, printing or weaving is gradually lost or is on the verge of extinction. This is due to craftsperson’s constant struggle to understand the tastes and preferences of the urban market and adapt himself to the technological changes. It is imperative to re-look at the traditional practices and incorporate improvised solutions to offer a better product for consumer satisfaction.

References

- Balaram—, Padmini T.—. (2001). Designing with Natural Dyes Proceeding of Convention of Natural Dyes edited by Deepti Gupta & M.L Gulrajani. Delhi: Department of Textile Technology, IIT.

- —, —. 1999. Bastar Textiles-Design, Motifs and Natural dyes. Madhya Pradesh Hastshilp Evam Hathkargha Vikas Nigam Limited.

- Bhavnani, Enakshi. 1969. Decorative Designs and Craftsmanship of India. Mumbai: D B Taraporevala Sons and Company Private Limited.

- Chishti, Kapur, Rta and Jain, Rahul. 2000. Handcrafted Indian Textiles – Traditions and Beyond. New Delhi: Roli Books Private Limited, Lustre Press Private Limited.

- —, —, — and Singh, Martand. 2010. Saris of India – Tradition and Beyond. New Delhi: Roli Books Private Limited, Lustre Press Private Limited.

- Dhamija, Jasleen and Jain, Jyotindra. 1989. Handwoven fabrics of India. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing Private Limited.

- Lynton, Linda 1995. The Sari – Styles, Patterns, History, Techniques. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Schoeser, Mary. 2003. World Textiles – a Concise History. London: Thames and Hudson, World of Art.

- Shukla, Hiralal. 1978. Bastar Ka Sanskritik Etihas. Nagpur: Vishwa Bharti Prakashan.

- Singh, Martand, Chishti, Kapur, Rta and Sanyal, Amba et al. 1989. Saris of India. Madhya Pradesh: Wiley Eastern Ltd. and New Delhi: Amar Vastra Kosh.

- Singh, A. K. and Misra, S. S. 2012. Jagdalpur – A Town in a Tribal Setting. Edited by Prof. K. K. Misra. Journal of the Anthropological Survey of India. 61 (1).

This content has been created as part of a project commissioned by the Directorate of Culture and Archaeology, Government of Chhattisgarh, to document the cultural and natural heritage of the state of Chhattisgarh.